Warning: Long post!

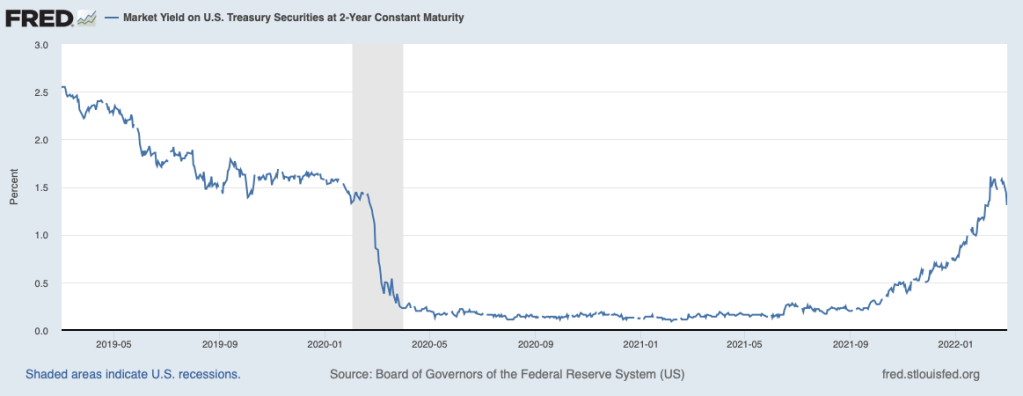

It now seems clear that the new monetary policy strategy the Fed announced in August 2020 was a decisive break with the past in one respect: With the new strategy, the Fed abandoned the approach dating to the 1980s of preempting inflation. That is, the Fed would no longer begin raising its target for the federal funds rate when data on unemployment and real GDP growth indicated that inflation was likely to rise. Instead, the Fed would wait until inflation had already risen above its target inflation rate.

Since 2012, the Fed has had an explicit inflation target of 2 percent. As we discussed in a previous blog post, with the new monetary policy the Fed announced in August 2020, the Fed modified how it interpreted its inflation target: “[T]he Committee seeks to achieve inflation that averages 2 percent over time, and therefore judges that, following periods when inflation has been running persistently below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.”

The Fed’s new approach is sometimes referred to as average inflation targeting (AIT) because the Fed attempts to achieve its 2 percent target on average over a period of time. But as former Fed Vice Chair Richard Clarida discussed in a speech in November 2020, the Fed’s monetary policy strategy might be better called a flexible average inflation target (FAIT) approach rather than a strictly AIT approach. Clarida noted that the framework was asymmetric, meaning that inflation rates higher than 2 percent need not be offset with inflation rates lower than 2 percent: “The new framework is asymmetric. …[T]he goal of monetary policy … is to return inflation to its 2 percent longer-run goal, but not to push inflation below 2 percent.” And: “Our framework aims … for inflation to average 2 percent over time, but it does not make a … commitment to achieve … inflation outcomes that average 2 percent under any and all circumstances ….”

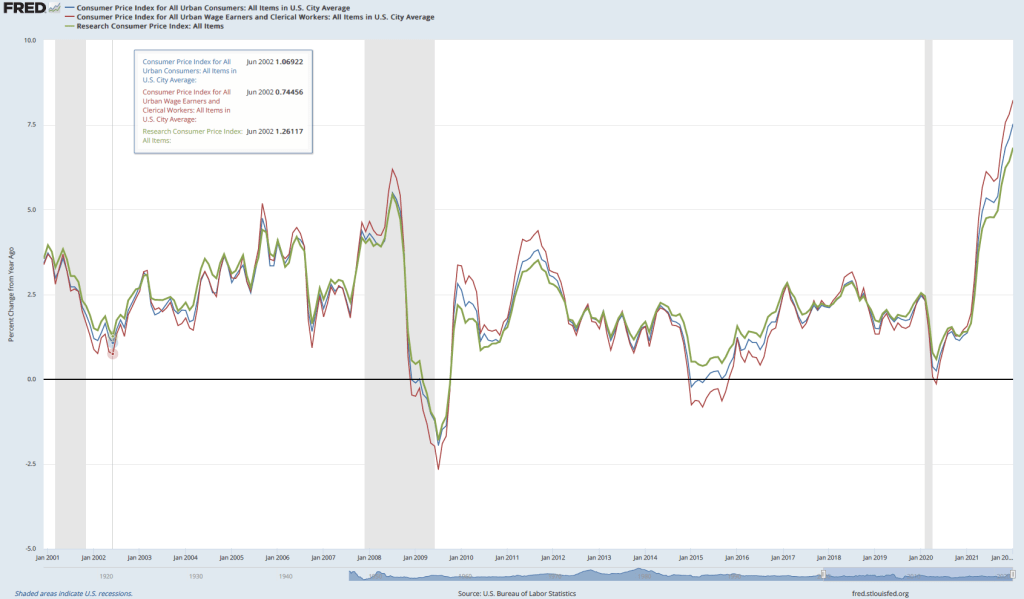

Inflation began to increase rapidly in mid-2021. The following figure shows three measure of inflation, each calculated as the percentage change in the series from the same month in the previous year: the consumer price index (CPI), the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) price index, and the core PCE—which excludes the prices of food and energy. Inflation as measured by the CPI is sometimes called headline inflation because it’s the measure of inflation that most often appears in media stories about the economy. The PCE is a broader measure of the price level in that it includes the prices of more consumer goods and services than does the CPI. The Fed’s target for the inflation rate is stated in terms of the PCE. Because prices of food and inflation fluctuate more than do the prices of other goods and services, members of the Fed’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) generally consider changes in the core PCE to be the best measure of the underlying rate of inflation.

The figure shows that for most of the period from 2002 through early 2021, inflation as measured by the PCE was below the Fed’s 2 percent target. Since that time, inflation has been running well above the Fed’s target. In February 2022, PCE inflation was 6.4 percent. (Core PCE inflation was 5.4 percent and CPI inflation was 7.9 percent.) At its March 2022 meeting the FOMC begin raising its target for the federal funds rate—well after the increase in inflation had begun. The Fed increased its target for the federal funds rate by 0.25 percent, which raised the target from 0 to 0.25 percent to 0.25 to 0.50 percent.

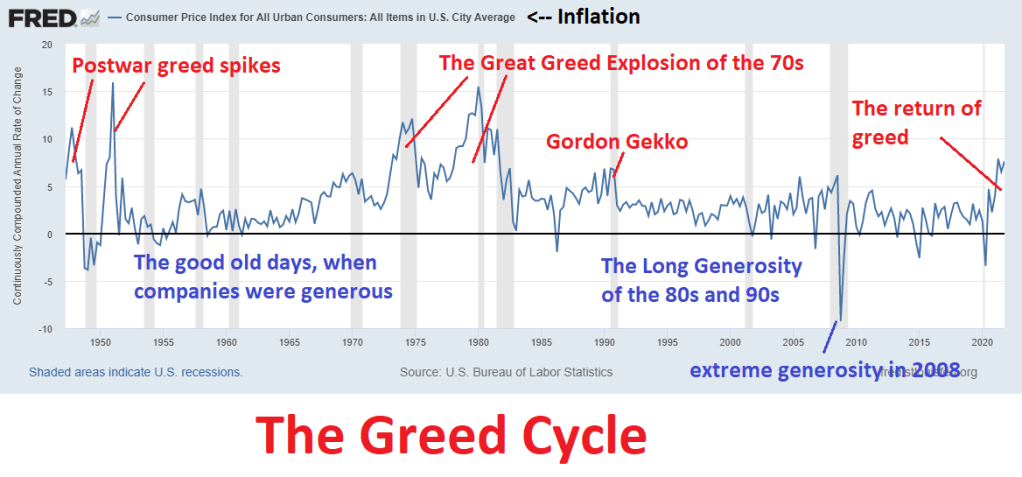

Should the Fed have taken action to reduce inflation earlier? To answer that question, it’s first worth briefly reviewing Fed policy during the Great Inflation of 1968 to 1982. In the late 1960s, total federal spending grew rapidly as a result of the Great Society social programs and the war in Vietnam. At the same time, the Fed increased the rate of growth of the money supply. The result was an end to the price stability of the 1952-1967 period during which the annual inflation rate had averaged only 1.6 percent.

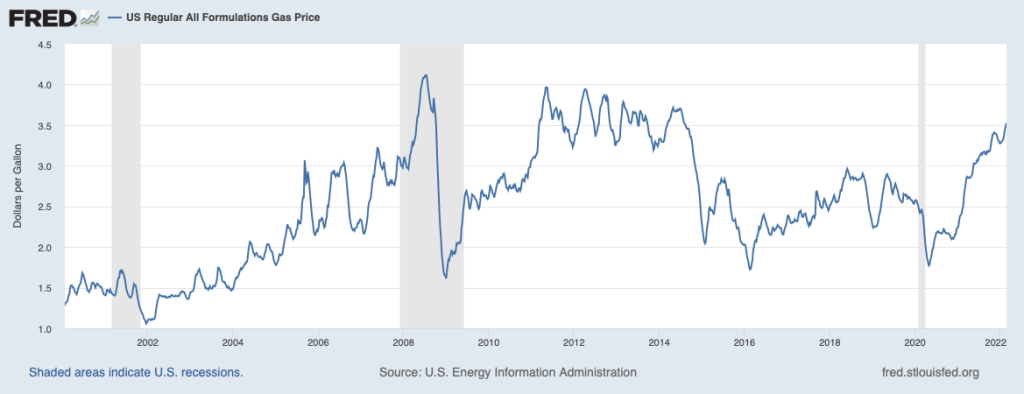

The 1973 and 1979 oil price shocks also contributed to accelerating inflation. Between January 1974 and June 1982, the annual inflation rate averaged 9.3 percent. This was the first episode of sustained inflation outside of wartime in U.S. history—until now. Although the oil price shocks and expansionary fiscal policy contributed to the Great Inflation, most economists, inside and outside of the Fed, eventually concluded that Fed policy failures were primarily responsible for inflation becoming so severe.

The key errors are usually attributed to Arthur Burns, who was Fed Chair from January 1970 to March 1978. Burns, who was 66 at the time of his appointment, had made his reputation for his work on business cycles, mostly conducted prior to World War II at the National Bureau of Economic Research. Burns was skeptical that monetary policy could have much effect on inflation. He was convinced that inflation was mainly the result of structural factors such as the power of unions to push up wages or the pricing power of large firms in concentrated industries.

Accordingly, Burns was reluctant to raise interest rates, believing that doing so hurt the housing industry without reducing inflation. Burns testified to Congress that inflation “poses a problem that traditional monetary and fiscal remedies cannot solve as quickly as the national interest demands.” Instead of fighting inflation with monetary policy he recommended “effective controls over many, but by no means all, wage bargains and prices.” (A collection Burns’s speeches can be found here.)

Few economists shared Burns’s enthusiasm for wage and price controls, believing that controls can’t end inflation, they can only temporarily reduce it while causing distortions in the economy. (A recent overview of the economics of price controls can be found here.) In analyzing this period, economists inside and outside the Fed concluded that to bring the inflation rate down, Burns should have increased the Fed’s target for the federal funds rate until it was higher than the inflation rate. In other words, the real interest rate, which equals the nominal—or stated—interest rate minus the inflation rate, needed to be positive. When the real interest rate is negative, a business may, for example, pay 6% on a bond when the inflation rate is 10%, so they’re borrowing funds at a real rate of −4%. In that situation, we would expect borrowing to increase, which can lead to a boom in spending. The higher spending worsens inflation.

Because Burns and the FOMC responded only slowly to rising inflation, workers, firms, and investors gradually increased their expectations of inflation. Once higher expectation inflation became embedded, or entrenched, in the U.S. economy it was difficult to reduce the actual inflation rate without increasing the target for the federal funds rate enough to cause a significant slowdown in the growth of real GDP and a rise in the unemployment rate. As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 17, Sections 17.2 and 17.3 (Economics, Chapter 27, Sections 27.2 and 27.3), the process of the expected inflation rate rising over time to equal the actual inflation rate was first described in research conducted separately by Nobel Laureates Milton Friedman and Edmund Phelps during the 1960s.

An implication of Friedman and Phelps’s work is that because a change in monetary policy takes more than a year to have its full effect on the economy, if the Fed waits until inflation has already increased, it will be too late to keep the higher inflation rate from becoming embedded in interest rates and long-term labor and raw material contracts.

Paul Volcker, appointed Fed chair by Jimmy Carter in 1979, showed that, contrary to Burns’s contention, monetary policy could, in fact, deal with inflation. By the time Volcker became chair, inflation was above 11%. By raising the target for the federal funds rate to 22%—it was 7% when Burns left office—Volcker brought the inflation rate down to below 4%, but only at the cost of a severe recession during 1981–1982, during which the unemployment rate rose above 10 percent for the first time since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Note that whereas Burns had largely failed to increase the target for the federal funds as rapidly as inflation had increased—resulting in a negative real federal funds rate—Volcker had raised the target for the federal funds rate above the inflation rate—resulting in a positive real federal funds rate.

Because the 1981–1982 recession was so severe, the inflation rate declined from above 11 percent to below 4 percent. In Chapter 17, Figure 17.10 (reproduced below), we plot the course of the inflation and unemployment rates from 1979 to 1989.

The Fed chairs who followed Volcker accepted the lesson of the 1970s that it was important to head off potential increases in inflation before the increases became embedded in the economy. For instance, in 2015, then Fed Chair Janet Yellen in explaining why the FOMC was likely to raise to soon its target for the federal funds rate noted that: “A substantial body of theory, informed by considerable historical evidence, suggests that inflation will eventually begin to rise as resource utilization continues to tighten. It is largely for this reason that a significant pickup in incoming readings on core inflation will not be a precondition for me to judge that an initial increase in the federal funds rate would be warranted.”

Between 2015 and 2018, the FOMC increased its target for the federal funds rate nine times, raising the target from a range of 0 to 0.25 percent to a range of 2.25 to 2.50 percent. In 2018, Raphael Bostic, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta justified these rate increases by noting that “… we shouldn’t forget that [the Fed’s] credibility [with respect to keeping inflation low] was hard won. Inflation expectations are reasonably stable for now, but we know little about how far the scales can tip before it is no longer so.”

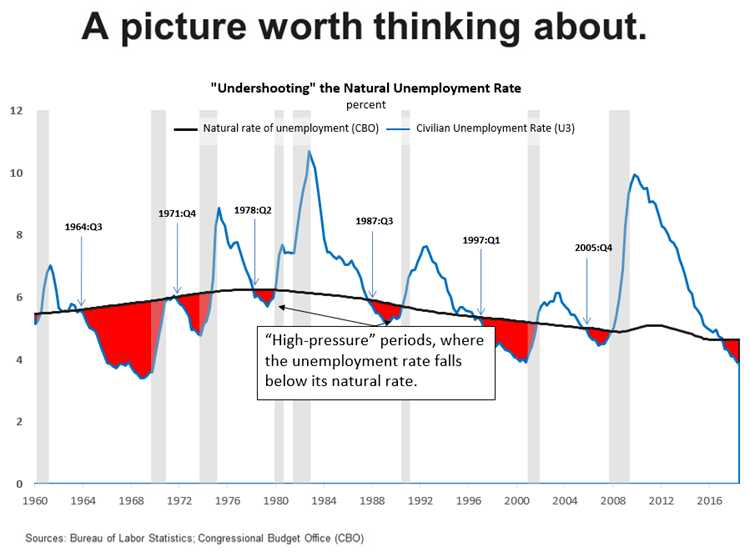

He used the following figure to illustrate his point.

Bostic interpreted the figure as follows:

“[The red areas in the figure are] periods of time when the actual unemployment rate fell below what the U.S. Congressional Budget Office now estimates as the so-called natural rate of unemployment. I refer to these episodes as “high-pressure” periods. Here is the punchline. Dating back to 1960, every high-pressure period ended in a recession. And all but one recession was preceded by a high-pressure period….

I think a risk management approach requires that we at least consider the possibility that unemployment rates that are lower than normal for an extended period are symptoms of an overheated economy. One potential consequence of overheating is that inflationary pressures inevitably build up, leading the central bank to take a much more “muscular” stance of policy at the end of these high-pressure periods to combat rising nominal pressures. Economic weakness follows [resulting typically, as indicated in the figure by the gray band, in a recession].”

By July 2019, a majority of the members of the FOMC, including Chair Powell, had come to believe that with no sign of inflation accelerating, they could safely cut the federal funds rate. But they had not yet explicitly abandoned the view that the FOMC should act to preempt increases in inflation. The formal change came in August 2020 when, as discussed earlier, the FOMC announced the new FAIT.

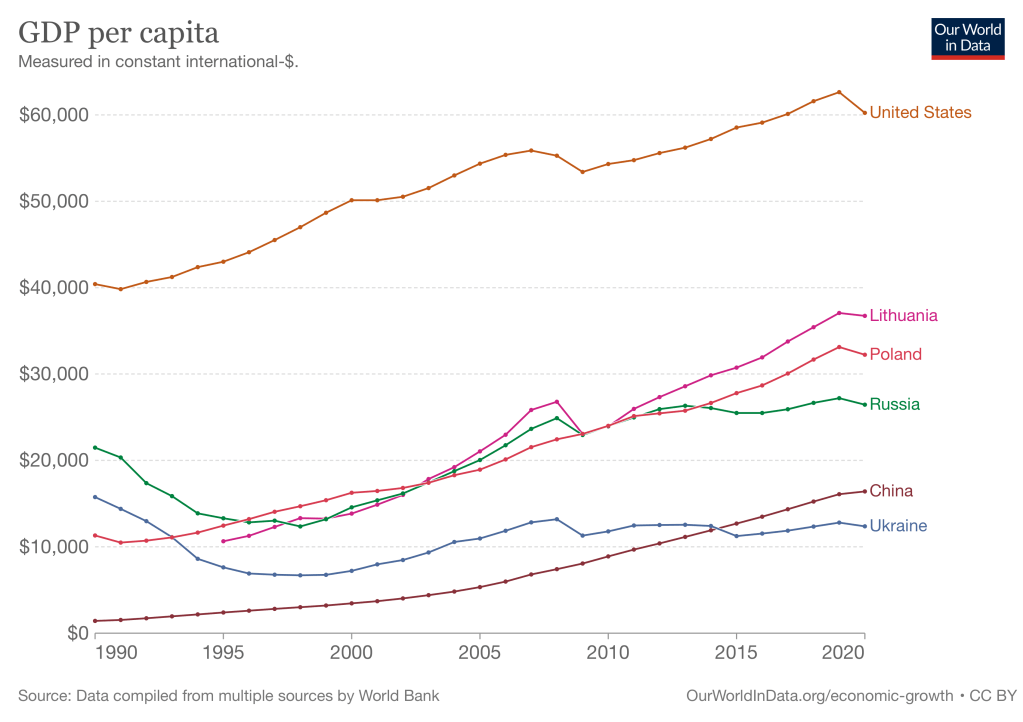

At the time the FOMC adopted its new monetary policy strategy, most members expected that any increase in inflation owing to problems caused by the Covid-19 pandemic—particularly the disruptions in supply chains—would be transitory. Because inflation has proven to be more persistent than Fed policymakers and many economists expected, two aspects of the FAIT approach to monetary policy have been widely discussed: First, the FOMC did not explicitly state by how much inflation can exceed the 2 percent target or for how long it needs to stay there before the Fed will react. The failure to elaborate on this aspect of the policy has made it more difficult for workers, firms, and investors to gauge the Fed’s likely reaction to the acceleration in inflation that began in the spring of 2021. Second, the FOMC’s decision to abandon the decades-long policy of preempting inflation may have made it more difficult to bring inflation down to the 2 percent target without causing a recession.

Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard recently remarked that “it is of paramount importance to get inflation down” and some Fed policymakers believe that the FOMC will have to begin increasing its target for the federal funds rate more aggressively. (The speech in which Governor Brainard discusses her current thinking on monetary policy can be found here.) For instance James Bullard, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, has argued in favor of raising the target to above 3 percent this year. With the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation running above 5 percent, it would take substantial increases int the target to achieve a positive real federal funds rate.

It is an open question whether Jerome Powell finds himself in a position similar to that of Paul Volcker in 1979: Rapid increases in interest rates may be necessary to keep inflation from accelerating, but doing so risks causing a recession. In a recent speech (found here), Powell pledged that: “We will take the necessary steps to ensure a return to price stability. In particular, if we conclude that it is appropriate to move more aggressively by raising the federal funds rate by more than 25 basis points at a meeting or meetings, we will do so.”

But Powell argued that the FOMC could achieve “a soft landing, with inflation coming down and unemployment holding steady” even if it is forced to rapidly increase its target for the federal funds rate:

“Some have argued that history stacks the odds against achieving a soft landing, and point to the 1994 episode as the only successful soft landing in the postwar period. I believe that the historical record provides some grounds for optimism: Soft, or at least softish, landings have been relatively common in U.S. monetary history. In three episodes—in 1965, 1984, and 1994—the Fed raised the federal funds rate significantly in response to perceived overheating without precipitating a recession.”

Some economists have been skeptical that a soft landing is likely. Harvard economist and former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers has been particularly critical of Fed policy, as in this Twitter thread. Summers concludes that: “I am apprehensive that we will be disappointed in the years ahead by unemployment levels, inflation levels, or both.” (Summers and Harvard economist Alex Domash provide an extended discussion in a National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper found here.)

Clearly, we are in a period of great macroeconomic uncertainty.