Supports: Macroeconomics, Chapter 18, Section 18.2; Economics, Chapter 28, Section 28.2; and Essentials of Economics, Chapter 19, Section 19.6.

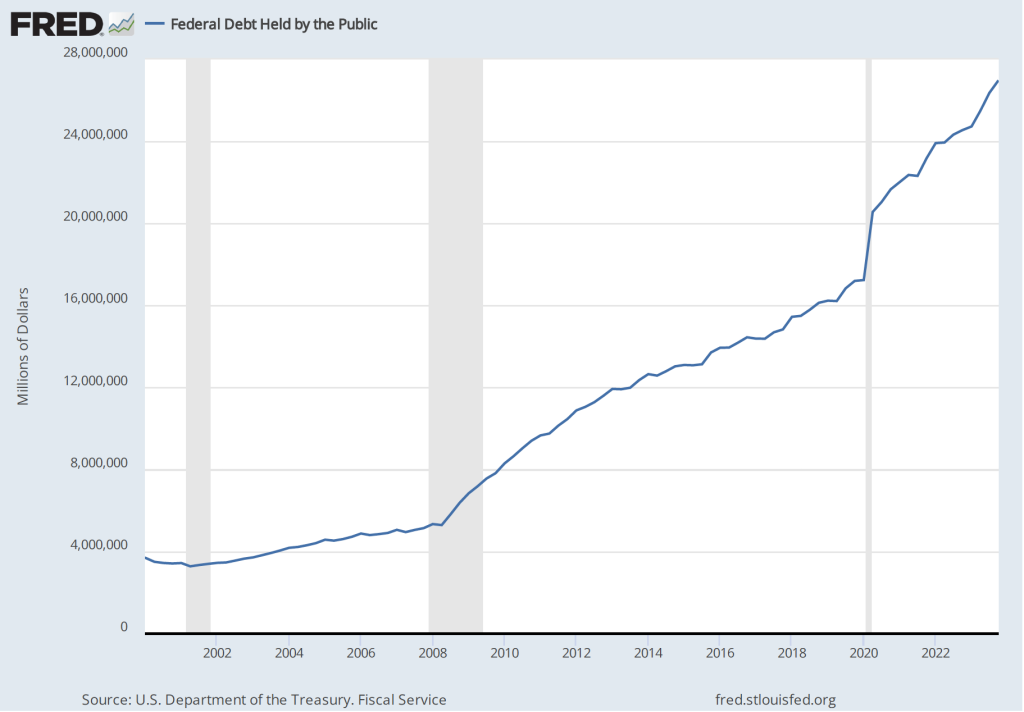

As the figure above shows, federal government debt, sometimes called the national debt, has been increasing rapidly in the years since the 2020 Covid pandemic. (The figure show federal government debt held by the public, which excludes debt held by federal government trust funds, such as the Social Security trusts funds.) The debt grows each year the federal government runs a budget deficit—that is, whenever federal government expenditures exceed federal government revenues. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) forecasts large federal budget deficits over the next 30 years, so unless Congress and the president increase taxes or cut expenditures, the size of the federal debt will continue to increase rapidly. (The CBO’s latest forecast can be found here. We discuss the long-run deficit and debt situation in this earlier blog post.)

When the federal government runs a budget deficit, the U.S. Treasury must sell Treasury bills, notes, and bonds to raise the funds necessary to bridge the gap between revenues and expenditures. (Treasury bills have a maturity—the time until the debt is paid off by the Treasury—of 1 year or less; Treasury notes have a maturity of 2 years to 10 years; and Treasury bonds have a maturity of greater than 10 years. For convenience, we will refer to all of these securities as “bonds.”) A recent article in the Wall Street Journal discussed the concern among some investors about the ability of the bond market to easily absorb the large amounts of bonds that Treasury will have to sell. (The article can be found here. A subscription may be required.)

According to the article, one source of demand is likely to be European and Japanese investors.

“The euro and yen are both sinking relative to the dollar, in part because the Bank of Japan is still holding rates low and investors expect the European Central Bank to slash them soon. That could increase demand for U.S. debt, with Treasury yields remaining elevated relative to global alternatives.”

a. What does the article mean by “the euro and the yen are both sinking relative to the dollar”?

b. Why would the fact that U.S. interest rates are greater than interest rates in Europe and Japan cause the euro and the yen to sink relative to the dollar?

c. If you were a Japanese investor, would you rather be invested in U.S. Treasury bonds when the yen is sinking relative to the dollar or when it is rising? Briefly explain.

Solving the Problem

Step 1: Review the chapter material. This problem is about the determinants of exchange rates, so you may want to review Macroeconomics, Chapter 18, Section 18.2, “The Foreign Exchange Market and Exchange Rates” (Economics, Chapter 28, Section 28.2; Essentials of Economics, Chapter 19, Section 19.6.)

Step 2: Answer part a. by explaining what it means that the euro and the yen “sinking relative to the dollar.” Sinking relative to the dollar means that the exchange rates between the euro and the dollar and between the yen and the dollar are declining. In other words, a dollar will exchange for more yen and for more euros.

Step 3: Answer part b. by explaining how differences in interest rates between countries can affect the exchange between the countries’ currencies. Holding other factors that can affect the attractiveness of an investment in a country’s bonds constant, the demand foreign investors have for a country’s bonds will depend on the difference in interest rates between the two countries. For example, a Japanese investor will prefer to invest in U.S. Treasury bonds if the interest rate is higher on Treasury bonds than the interest rate on Japanese government bonds. So, if interest rates in Europe decline relative to interest rates in the United States, we would expect that European investors will increase their investments in U.S. Treasury bonds. To invest in U.S. Treasury bonds, European investors will need to exhange euros for dollars, causing the supply curve for euros in exchange for dollars to shift to the right, reducing the value of the euro.

Step 4: Answer part c. by discussing whether if you were a Japanese investor, you would you rather be invested in U.S. Treasury bonds when the yen is sinking relative to the dollar or when it is rising. In answering this part, you should draw a distinction between the situation of a Japanese investor who already owns U.S. Treasury bonds and one who is considering buying U.S. Treasury bonds. A Japanese investor who already owns U.S. Treasury bonds would definitely prefer to own them when the value of the yen if falling against the dollar. In this situation, the investor will receive more yen for a given amount of dollars the investor earns from the Treasury bonds. A Japanese investor who doesn’t currently own U.S. bonds, but is thinking of buying them, would want the value of the yen to be increasing relative to the dollar because then the investor would have to pay fewer yen to buy a Treasury bond with a price in dollars, all other factors being equal. (The face value of a Treasury bond is $1,000, although at any given time the price in the bond market may not equal the face value of the bond.) If the interest rate difference between U.S. and Japanese bonds is increasing at the same time as the value of the yen is decreasing (as in the situation described in the article) a Japanese investor would have to weigh the gain from the higher interest rate against the higher price in yen the investor would have to pay to buy the Treasury bond.