The Financial Times recently interviewed Glenn. Here is an edited version. The full interview can be found here.

Financial Times (Gillian Tett, editor-at-large for the United States): Gross domestic product data show that the economy is rebounding very fast from the pandemic; the Federal Reserve just said that it doesn’t intend to raise rates any time soon; and President Joe Biden has pledged a massive fiscal package. So what is your forecast for the American economy?

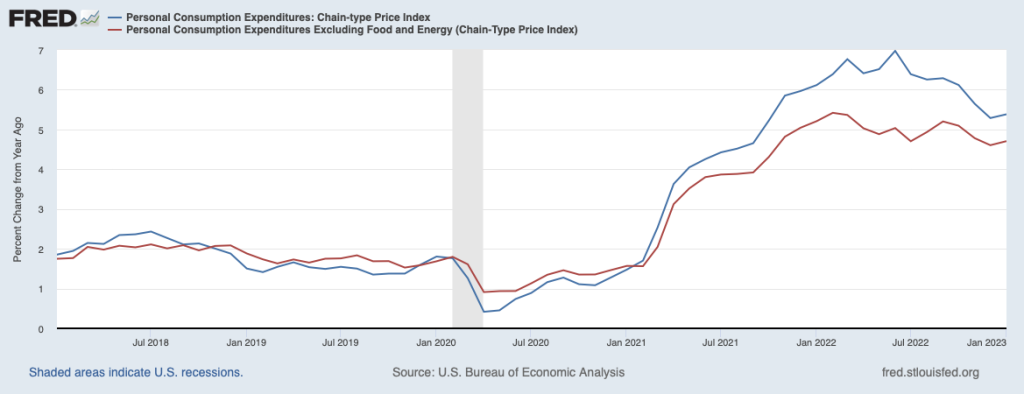

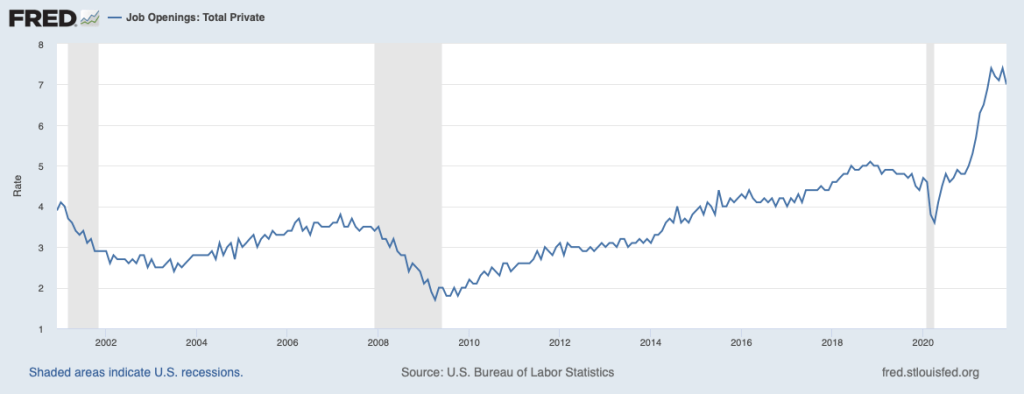

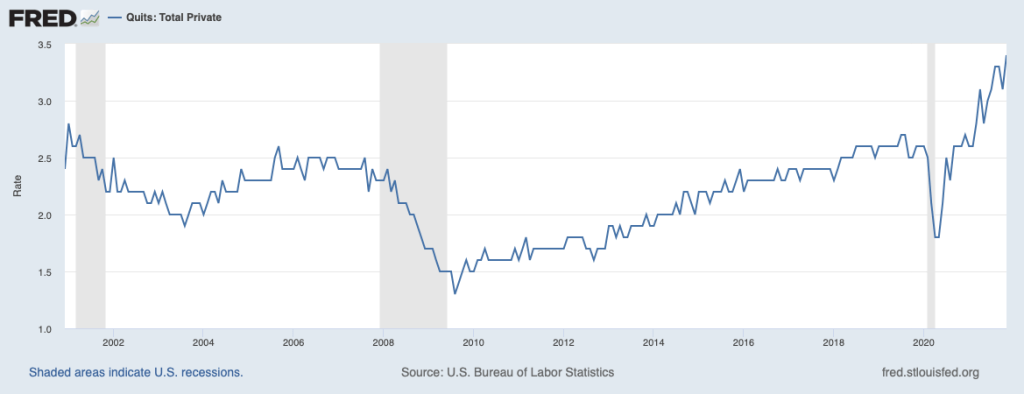

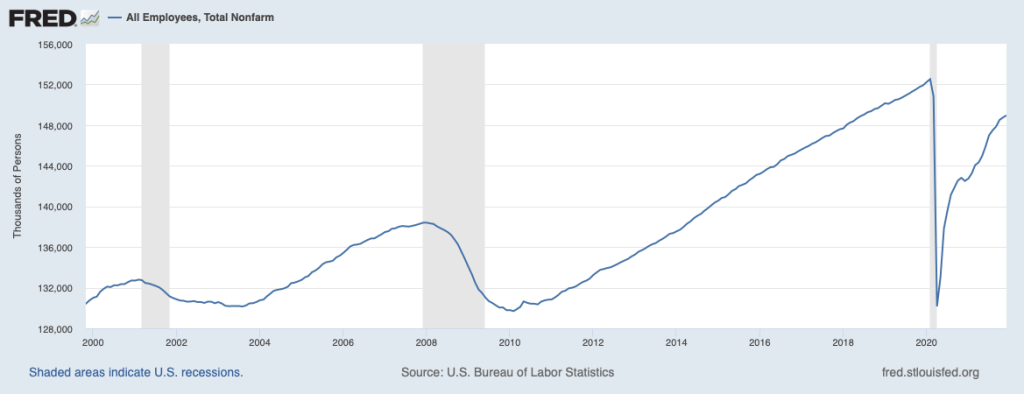

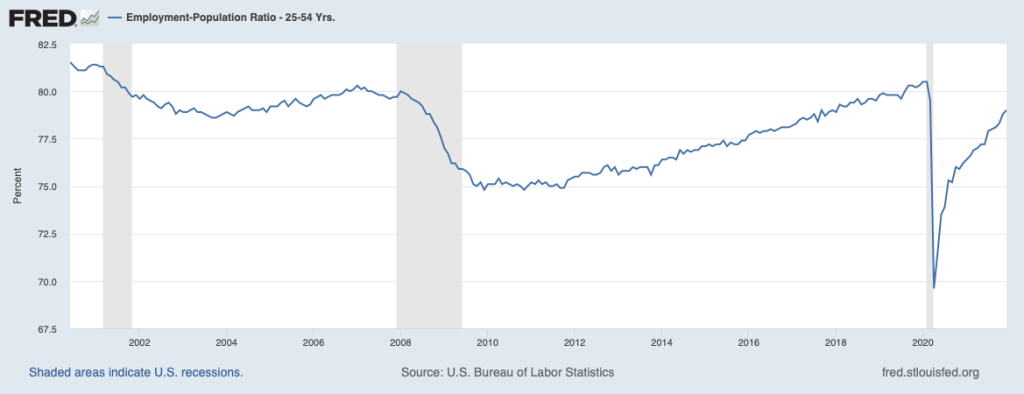

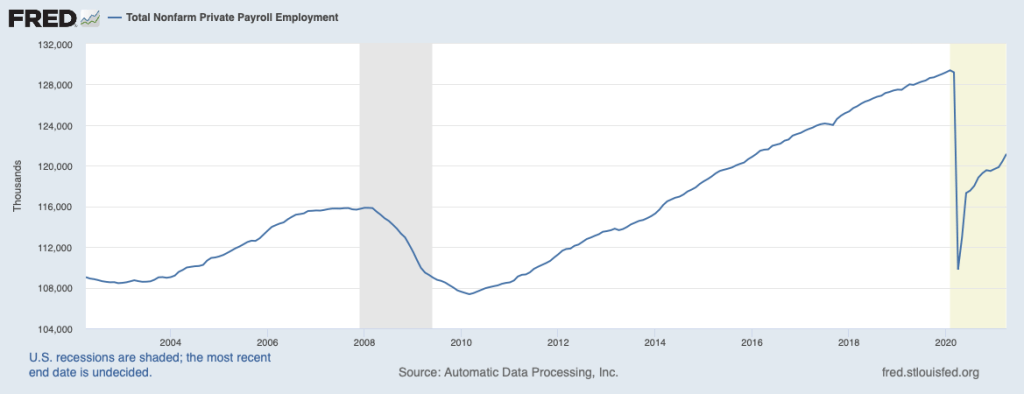

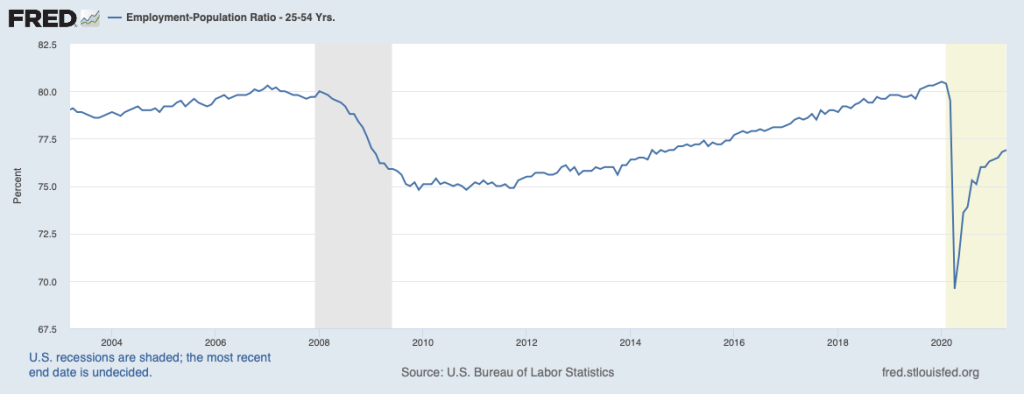

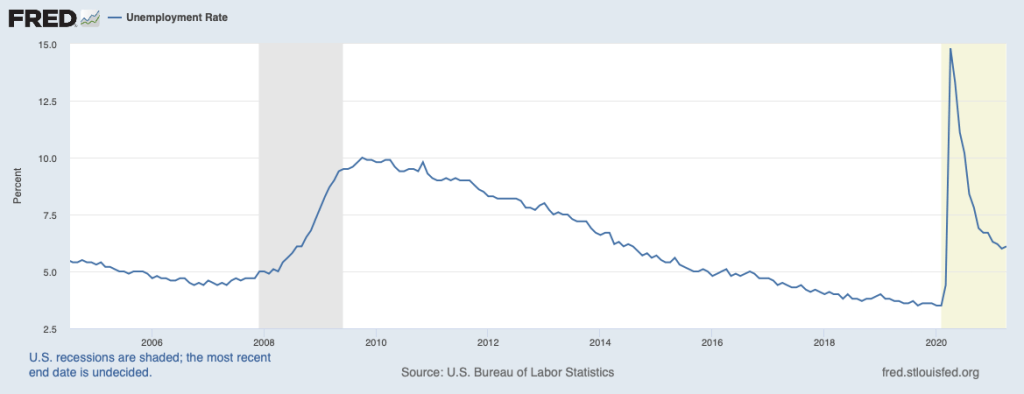

Glenn: Re-opening as the virus recedes would always lead to a very significant pop in GDP growth. So the near-term is not really the big question. There will certainly be a transitory increase in inflation. But I think the Fed on balance is correct, that boost is likely to be transitory. My worry is when I hear the Fed talk, as its chair Jay Powell has done, about wanting to watch for labor market “re-healing” to finish. The problem in the labor market is [largely] structural. Just running the economy hot by the Fed doesn’t fix that.

On fiscal policy, this is not just a “boost”.… The American Rescue Plan was intended as stimulus. But the American Jobs Act, the American Families Plan, those are really a remaking of the size of government. It has to be paid for and arithmetically can’t be paid for by taxes on the rich. There’s just not enough there. So the honest conversation with the American people is a matter of public choice: if you want a big government that does what President Biden wants [it to do], you’ll have to pay for it.

GT: How confident are you that inflation pressures are transitory?

GH: One can never be completely confident, but I think if the Fed had a clearer policy story I could be confident that commodity price increases are transitory. What worries me is the Fed thinking it can lean against structural changes in the labor market with monetary policy. One might worry a bit about inflation risks in the long-term—some of the structural headwinds against inflation to do with demography and growth in the emerging world, particularly in China, are going away.

GT: Do you think that the Fed should be indicating that it’s willing to raise rates if inflation rises?

GH: I think the Fed is unlikely to do that. [But] one of the reasons you are seeing implied volatility in rates and credit markets so high relative to equities, is the fear in the bond market that, maybe, the Fed is saying one thing but if backed into the corner could do another. Remember that the Fed bought around half of Treasury issues last year, and owns 40 per cent of all of the outstanding 10-year plus maturity treasuries, so the Fed’s thoughts there, which aren’t really clear to the bond market, are very, very important.

GT: Larry Summers has said this is way too much [stimulus], way too fast and will create inflation risks. You and Larry don’t often agree, but would you agree on this?

GH: I would agree on the risk, but it’s [not] the problem that is worrying me the most. What worries me even more is [in trying to] create a government that large . . . if you want a government that does those things, tax burdens will have to be higher.

If you look at the math on the tax burden, the [proposed] corporate tax increase or capital gains tax increase are not remotely large enough. The other structural thing that worries me is that I do see productivity reductions and investment reductions as a result of these large tax increases.

GT: Biden said if you are earning less than $400,000 a year you will not see your taxes go up.

GH: Well, it’s just not true, [neither] in the near-term [nor] the long-term. Take the corporate tax. Many economists have concluded that much of the burden of the corporate tax is borne by workers. In the 1970s and early 1980s, we thought it was capital that bore the burden of the corporate taxes. [But] that is not what economists believe today. So you simply cannot say that people who make less than $400,000 aren’t going to bear a part of the burden of the tax.

Likewise with capital gains, the president says: “I’m only going after 0.3 per cent of taxpayers,” meaning [those] that make more than a million dollars a year and have capital gains. But those individuals don’t have 0.3 per cent of the capital gains—they likely have the bulk of them. So if there are any effects on risk-taking, on saving and investment, the [risks] are very large.

Those effects are borne by the economy, not by the top 0.3 per cent …. And in the longer term … if you look at the budget math here, there’s going to be a large revenue hole. Somebody has to pay for it.

GT: Well, what about that “somebody” being companies?

GH: Let’s put the tax changes into two buckets. On the rates, I don’t think we want to go as high as the president is proposing, certainly not back to the old rates. On the base, president Biden is proposing a tax increase by base broadening—it’s a very, very big change. I expect companies will acknowledge they need to pay some minimum level, but the math isn’t going to add up.

GT: What about taxes under the guise of climate change action, such as a fuel tax or value added tax?

GH: I think it’s a great idea. For years I have supported a carbon tax because I do believe that it is one of the best ways to deal with climate change. I’m very skeptical of subsidies in green things but if you put a price on carbon, businesspeople will rush around and innovate and do it efficiently and it does not have to be regressive .…

About [a value-added tax] VAT—there is no question that if we want the government President Biden is suggesting, you absolutely have to have a VAT.

European states that have much bigger [state sectors] than the American state as a share of GDP are not financed with taxes on capital. In fact, in many European countries capital taxes are lower than they are in the United States. They’re financed by consumption taxes [such as the VAT].

…

GT: Why do you think Biden’s package is undermining productivity?

GH: Let me just take one step back. Some discussions of secular stagnation come from insufficient aggregate demand. Another school of thought thinks that structurally we have a problem with productivity growth, in terms of the supply side of the economy and the economy’s potential to grow. That is where I’m coming from. The tax plans are definitely anti-investment, as the lack of capital deepening explains low productivity growth and capital gains tax increases can affect risk-taking. There’s certainly nothing to enhance productivity [in Biden’s plans] and a lot to discourage productivity.

It is not just the tax policy. I worry about a monetary policy that could lead to zombification of firms—an environment of very low interest rates that sustain low-productivity firms. To President Biden’s credit, pieces of what he’s proposing that are true infrastructure could, in fact, raise productivity, but that is a small part of what he’s actually calling infrastructure.

GT: Are you concerned about a future debt crisis?

GH: Well, we are the reserve currency country, and we are borrowing in our currency, so I think a slow and steady malaise is more likely. To give a practical example, the Medicare trust fund could run out of money within a year or so, social security within five or so years. That will force discussions in Washington as to whether the public may wish to have a government this size.

GT: So you don’t expect a debt crisis per se because of the reserve currency status?

GH: [Not] at the moment.

GT: Should Republicans be co-operating to create a bipartisan bill?

GH: You could get bipartisan support for a new “GI bill” to prepare workers to adjust from the Covid world. For example, support in community colleges.

I’m not talking about free community college but supply side support—increasing their capacity to train people. Where you won’t get bipartisan support is [for] the notion that we need to move away from a work-supported social insurance system to a broader cradle-to-grave safety net.

The administration really fuzzed that up by calling it an infrastructure bill. Infrastructure doesn’t have to be just roads and bridges and airports—it could be broadband. But not healthcare.

GT: Are childcare support and elderly support part of “infrastructure”?

GH: No—those are social spending.

GT: One of the interesting ways you frame this debate is with the contrast between Keynes and Hayek, i.e. whether you’re trying to prop up the current system or encourage more rapid transformation. What do you mean?

GH: You could think of Covid [in terms of] a Keynesian response — we have a collapse in demand. The Keynesian response is not fanciful. But Hayek would say the new world after Covid isn’t going to look like the old world, so why support every single business? Both are right. We did a good job in policy on the Keynesian part. [But] we’ve done less well [thinking about Hayek].

GT: What do you think about Larry Summer’s concept of secular stagnation?

GH: There’s a scene in Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, when Scrooge asks, [something like] “are these the shadows of things that are or might be?”. I feel the same way about Bob Gordon’s descriptions of the American economy — Larry and Bob are talking about the shadows of things that could be if we have bad enough public policy, going back to the anti-productivity story. But I don’t think they’re inevitable.

Every businessperson with whom I speak is pretty optimistic about the technology frontier in productivity. If there’s a reason for pessimism, it’s more about the political system’s ability and willingness to let that productivity growth [run free].

GT: Do you think that the Republican party knows what it stands for with economics?

GH: … [An] approach Republicans could take is to go past the neoliberalism to liberalism (with a small L), to Adam Smith. He was anti-mercantilist—that’s what got him angry in The Wealth of Nations—and he was very interested in the ability of everybody in the economy to compete.

So a new Republican agenda might do more to help people compete—that sounds more like Lincoln, or like Roosevelt’s GI bill. In that lies a new agenda. But I don’t see the party really moving in that direction.

GT: What about the second book of Smith’s, The Theory of Moral Sentiments?

GH: Smith referred to “mutual sympathy”, which today we would call empathy. Forward-leaning businesspeople and business leaders think that way. I don’t see [the environmental, social, and governance] ESG [approach to investing] as somehow an enemy of shareholders—this isn’t Milton Friedman versus socialism—it’s more a matter of what really is in the long-term interest of the firm.

Remember, Smith railed against the British East India Company, which he thought of as a cancer. He thought you had to be very careful in the social framing of corporations. Businesspeople today need to understand the corporate structure is a social gift. In fact, capitalism is a social gift. If the public doesn’t want it, it won’t happen.

GT: I have a book coming out in a few weeks’ time that stresses this social and cultural aspect of business and finance and economics, and argues that business leaders need to move beyond tunnel vision to use lateral vision. Do you agree with this?

GH: Yes. When I teach students political economy, I remind them that great thinkers like a Friedman or Hayek or Smith wrote [for] the times in which they lived. Friedman and Hayek were writing in response to a very slovenly and inefficient corporatist economic system and were horrified by fascism. If Ronald Reagan were with us today, I don’t think he would be the 1980s Ronald Reagan. If Friedman and Hayek were with us today, they might have a different view. Context shifts.

GT: Friedman was also operating when people assumed that they could outsource the difficult social decisions to government and when there wasn’t radical transparency and customers, clients and employees couldn’t see exactly what firms were doing. Does that matter?

GH: Yes. If Friedman were here he might correctly remind us that there are big social externalities no one company can fix. But there is no reason businesspeople can’t be leaders. When the Marshall Plan was passed, that was not because Congress in its great wisdom decided to do something. It was because the business community came together and said: “Good Lord, we are going to have communism in western Europe and what’s that going to do to our economic system?” They pushed Congress. I understand that [today business is] afraid. But it’s not an excuse not to act. At many companies, their own employees are going to put pressure [on them to act].

GT: You are starting to see a level of company collaboration which was unimaginable when we had Thatcherism and Reaganism. Will this last?

GH: I do [think so] and Hayek would have celebrated this co-ordinated response because it bubbled up from the bottom. If you compare the production of vaccines, which was largely a private-sector activity, to the distribution of vaccines, which was more a public-sector activity, I think we know which one seemed to work better.

There are things that could help that—imagine if Biden put applied research centers all around the country that were linked with universities. That might help companies fix localities, as well as solving big problems like vaccines.

…

GT: Are you concerned that we have an ESG bubble?

GH: I am, in several aspects. We are running the risk of industrial policy and rent seeking, with just subsidizing “green things.” I also worry about how CEOs can deal with this—you don’t want the CEO spending half of his or her day responding to social concerns.

GT: What about protectionism? Can the Republicans present an alternative voice on this?

GH: I hope so, but I’m not sure. Like almost all economists … I believe in free trade. So why is something that is obvious in Econ 101 not so popular with the public?

I think for two reasons. One is whenever your Econ 101 professor talked about the gains from trade, he or she always [had] the idea that there would be losers, but compensation would somehow occur—and it hasn’t.

[Second] free trade is one of those examples, like the old classical gold standard, of a system that’s outside-in. You have to sign up for the rules of the game and then you just adjust. I think we need to go back to a period that says, look, we do need to understand domestic constituencies. That could mean much more support for training, it could be wage insurance, it could be lots of things rather than just saying free trade.

GT: So it’s about trying to talk about free trade with both parts of Adam Smith.

GH: Yes, exactly. Even Smith, who was the champion for openness, would not have countenanced whole areas just being left behind. Smith talked a lot about places—he said something like a man is a sort of luggage that’s hard to move, meaning you really have to look after places, not just jobs . . . its culture.

GT: Hey, anthropology can mingle with economics!

GH: Exactly—two social sciences, peas in a pod.

GT: So what’s happening to the economics profession? With issues like [the debate around Larry Summers’ criticism of Biden’s policies] are we seeing a tribal warfare break out between economists? Is there a rethink of economics? Is Biden moving away from them?

GH: Well, let me start with some good news: the young stars in the [economics] profession today tend to be people who are talking about big problems with new tools and techniques, ranging from development to monetary policy to labor markets. I think that’s entirely healthy.

I think the government needs people who have big macro views [too]. If I were in Janet Yellen’s shoes, I’d want to be talking to economists who could continue to give me that perspective, but also get micro perspectives from labor and financial markets. So there needn’t be a war. [But] I do worry from the way the Biden administration is talking about policies that economists just aren’t very involved at all. That’s not the first administration I’ve seen that happen—but it is a concern for the economics profession.