Join authors Glenn Hubbard & Tony O’Brien as they react to the jobs report of over 300K jobs created which was way over expectations of about 200K. They consider the impact of this report as the Fed considers the next steps for the economy. Are we on a glide path for a soft landing at 2% inflation or will the Fed reconsider its long-standing target by adopting a higher 3% target? Glenn and Tony offer interesting viewpoints on where this is headed.

Category: Ch20: Economic Growth, the Financial System, and Business Cycles

Key Macro Data Series during the Time Since the Arrival of Covid–19 in the United States

A bookstore in New York City closed during Covid. (Photo from the New York Times)

Four years ago, in mid-March 2020, Covid–19 began to significantly affect the U.S. economy, with hospitalizations rising and many state and local governments closing schools and some businesses. In this blog post we review what’s happened to key macro variables during the past four years. Each monthly series starts in February 2020 and the quarterly series start in the fourth quarter of 2019.

Production

Real GDP declined by 5.8 percent from the fourth quarter of 2019 to the first quarter of 2020 and by an additional 28.0 percent from the first quarter of 2020 to the second quarter. This decline was by far the largest in such a short period in the history of the United States. From the second quarter to the third quarter of 2020, as businesses began to reopen, real GDP increased by 34.8 percent, which was by far the largest increase in a single quarter in U.S. history.

Industrial production followed a similar—although less dramatic—path to real GDP, declining by 16.8 percent from February 2020 to April 2020 before increasing by 12.3 percent from April 2020 to June 2020. Industrial production did not regain its February 2020 level until March 2022. The swings in industrial production were smaller than the swings in GDP because industrial production doesn’t include the output of the service sector, which includes firms like restaurants, movie theaters, and gyms that were largely shutdown in some areas. (Industrial production measures the real output of the U.S. manufacturing, mining, and electric and gas utilities industries. The data are issued by the Federal Reserve and discussed here.)

Employment

Nonfarm payroll employment, collected by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) in its establishment survey, followed a path very similar to the path of production. Between February and April 2020, employment declined by an astouding 22 million workers, or by 14.4 percent. This decline was by far the largest in U.S. history over such a short period. Employment increased rapidly beginning in April but didn’t regain its February 2020 level until June 2022.

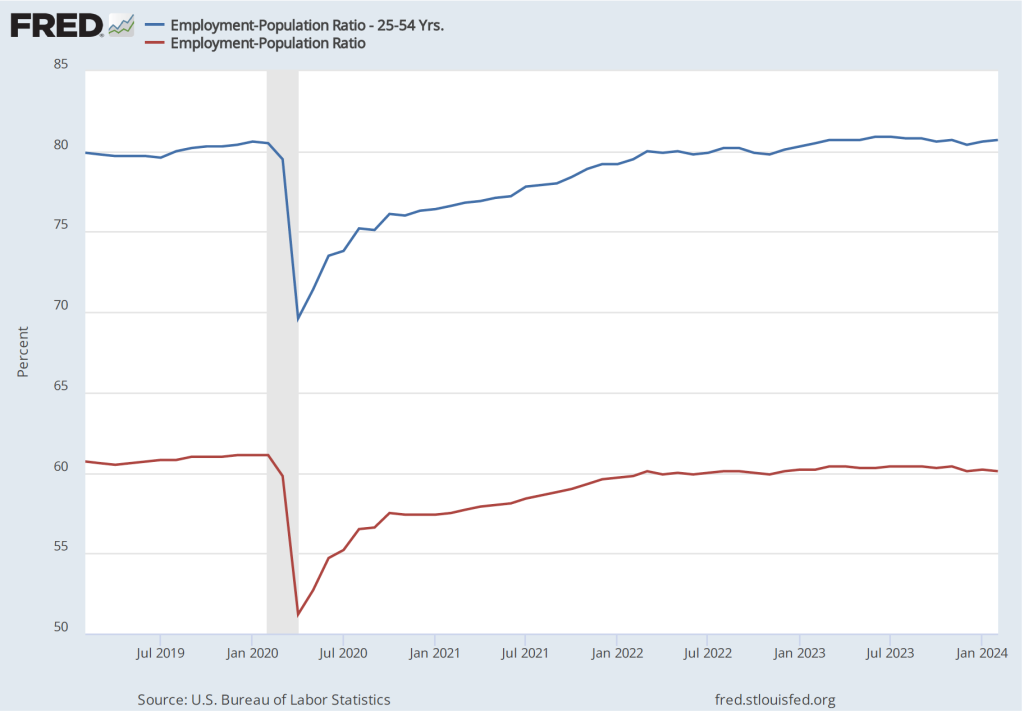

The employment-population ratio measures the percentage of the working-age population that is employed. It provides a more comprehensive measure of an economy’s utilization of available labor than does the total number of people employed. In the following figure, the blue line shows the employment-population ratio for the whole working-age population and the red line shows the employment-population ratio for “prime age workers,” those aged 25 to 54.

For both groups, the employment-population ratio plunged as a result of Covid and then slowly recovered as the production began increasing after April 2020. The employment-population ratio for prime age workers didn’t regain its February 2020 value until February 2023, an indication of how long it took the labor market to fully overcome the effects of the pandemic. As of February 2024, the employment-population ratio for all people of working age hasn’t returned to its February 2020 value, largely because of the aging of the U.S. population.

Average weekly hours worked followed an unusual pattern, declining during March 2020 but then increasing to beyond its February 2020 level to a peak in April 2021. This increase reflects firms attempting to deal with a shortage of workers by increasing the hours of those people they were able to hire. By April 2023, average weekly hours worked had returned to its February 2020 level.

Income

Real average hourly earnings surged by more than six percent between February and April 2020—a very large increase over a two-month period. But some of the increase represented a composition effect—as workers with lower incomes in services industries such as restaurants were more likely to be out of work during this period—rather than an actual increase in the real wages received by people employed during both months. (Real average hourly earnings are calculated by dividing nominal average hourly earnings by the consumer price index (CPI) and multiplying by 100.)

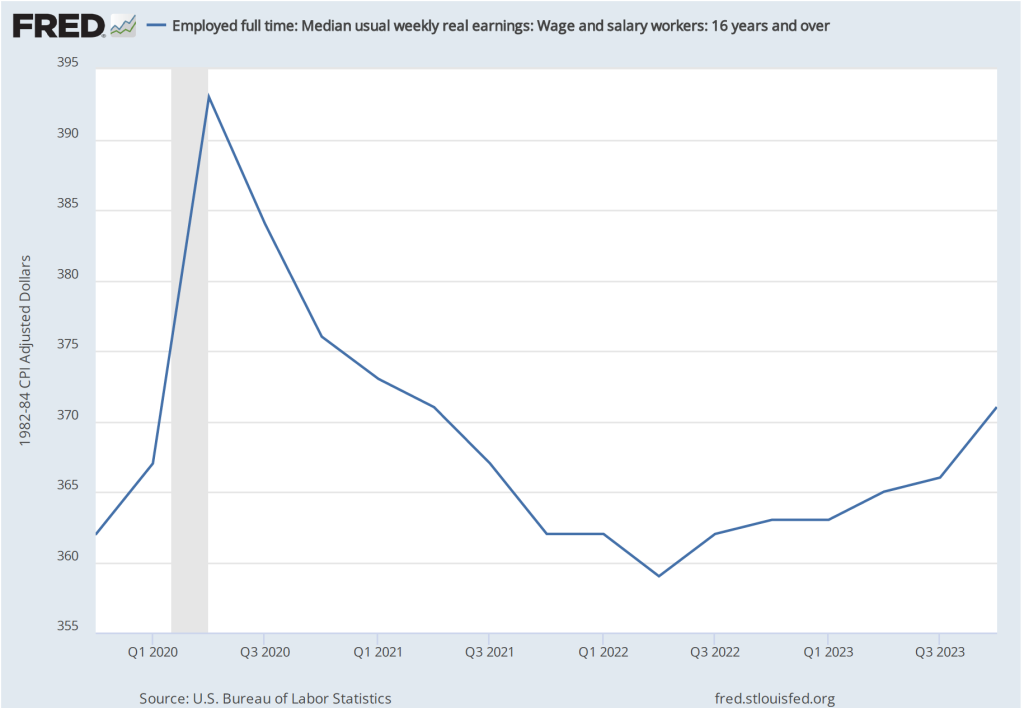

Median weekly real earnings, because it is calculated as a median rather than as an average (or mean), is less subject to composition effects than is real average hourly earnings. Median weekly real earnings increased sharply between February and April of 2020 before declining through June 2022. Earnings then gradually increased. In February 2024 they were 2.5 percent higher than in February 2020.

Inflation

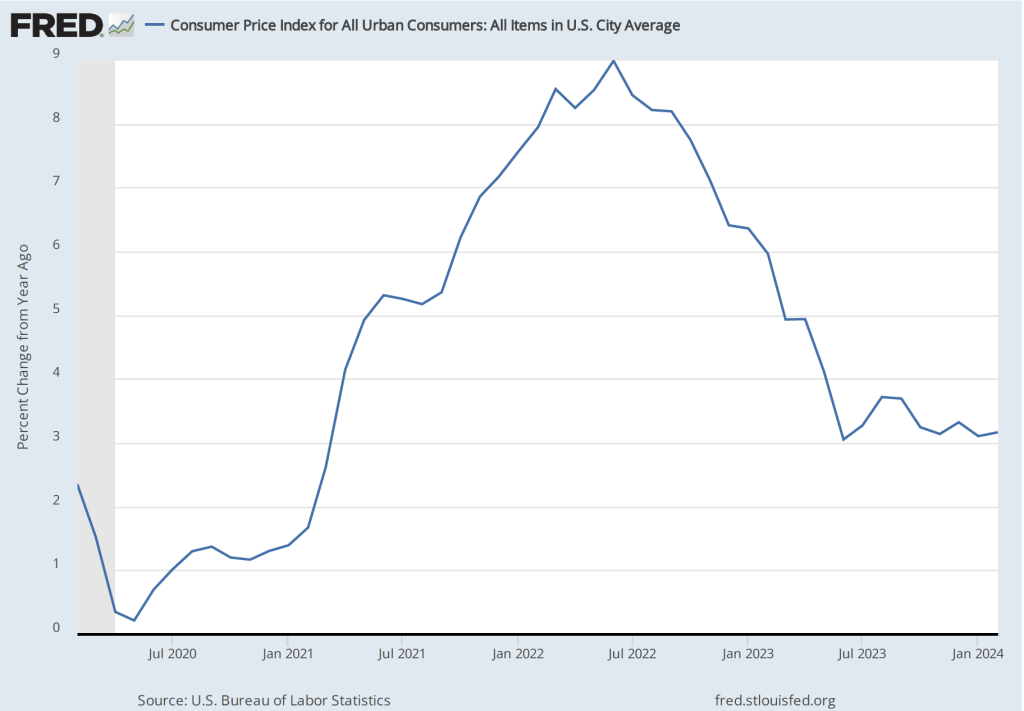

The inflation rate most commonly mentioned in media reports is the percentage change in the CPI from the same month in the previous year. The following figure shows that inflation declined from February to May 2020. Inflation then began to rise slowly before rising rapidly beginning in the spring of 2021, reaching a peak in June 2022 at 9.0 percent. That inflation rate was the highest since November 1981. Inflation then declined steadily through June 2023. Since that time it has fluctuated while remaining above 3 percent.

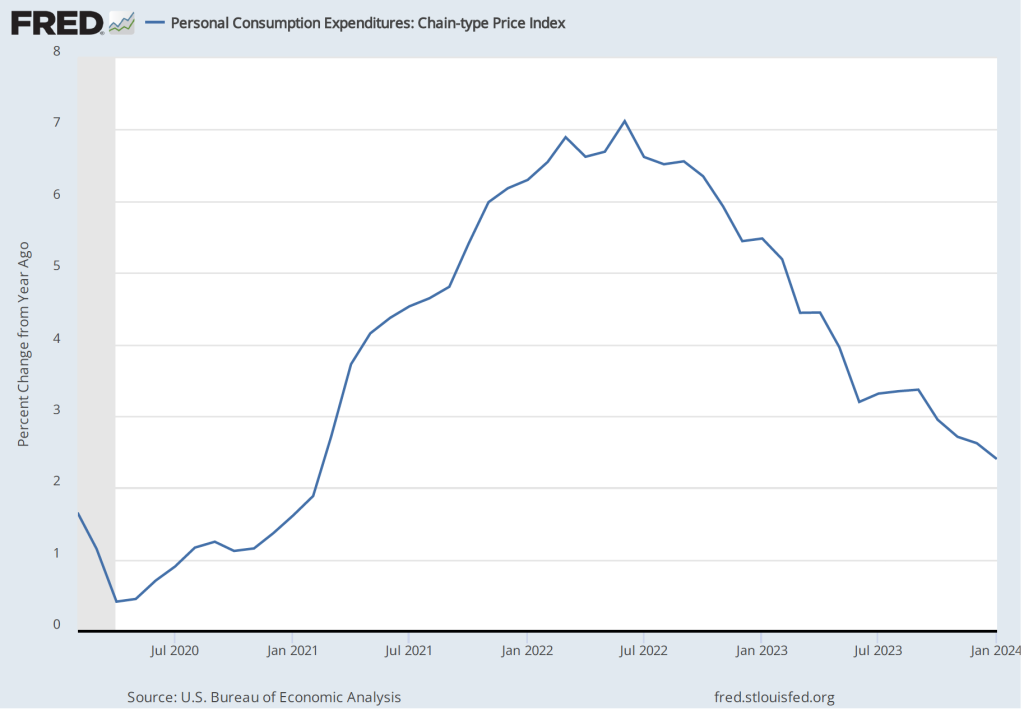

As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 15, Section 15.5 (Economics, Chapter 25, Section 25.5), the Federal Reserve gauges its success in meeting its goal of an inflation rate of 2 percent using the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index. The following figure shows that PCE inflation followed roughly the same path as CPI inflation, although it reached a lower peak and had declined below 3 percent by November 2023. (A more detailed discussion of recent inflation data can be found in this post and in this post.)

Monetary Policy

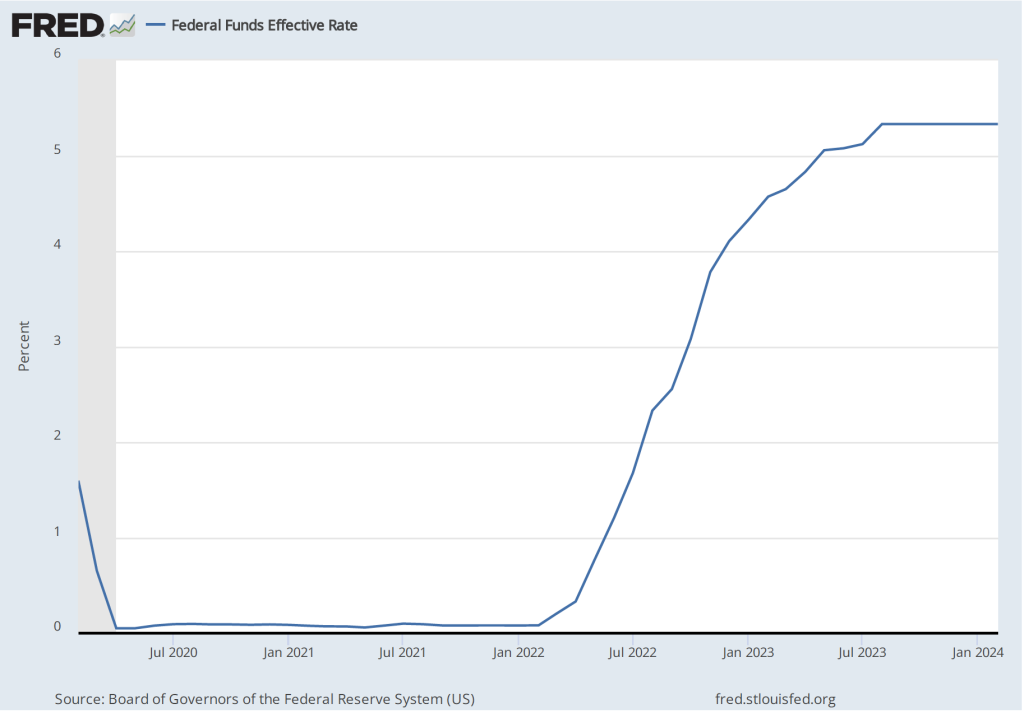

The following figure shows the effective federal funds rate, which is the rate—nearly always within the upper and lower bounds of the Fed’s target range—that prevails during a particular period in the federal funds market. In March 2020, the Fed cut its target range to 0 to 0.25 percent in response to the economic disruptions caused by the pandemic. It kept the target unchanged until March 2022 despite the sharp increase in inflation that had begun a year earlier. The members of the Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) had initially hoped that the surge in inflation was largely caused by disuptions to supply chains and would be transitory, falling as supply chains returned to normal. Beginning in March 2022, the FOMC rapidly increased its target range in response to continuing high rates of inflation. The targer range reached 5.25 to 5.50 percent in July 2023 where it has remained through March 2024.

Although the money supply is no longer the focus of monetary policy, some economists have noted that the rate of growth in the M2 measure of the money supply increased very rapidly just before the inflation rate began to accelerate in the spring of 2021 and then declined—eventually becoming negative—during the period in which the inflation rate declined.

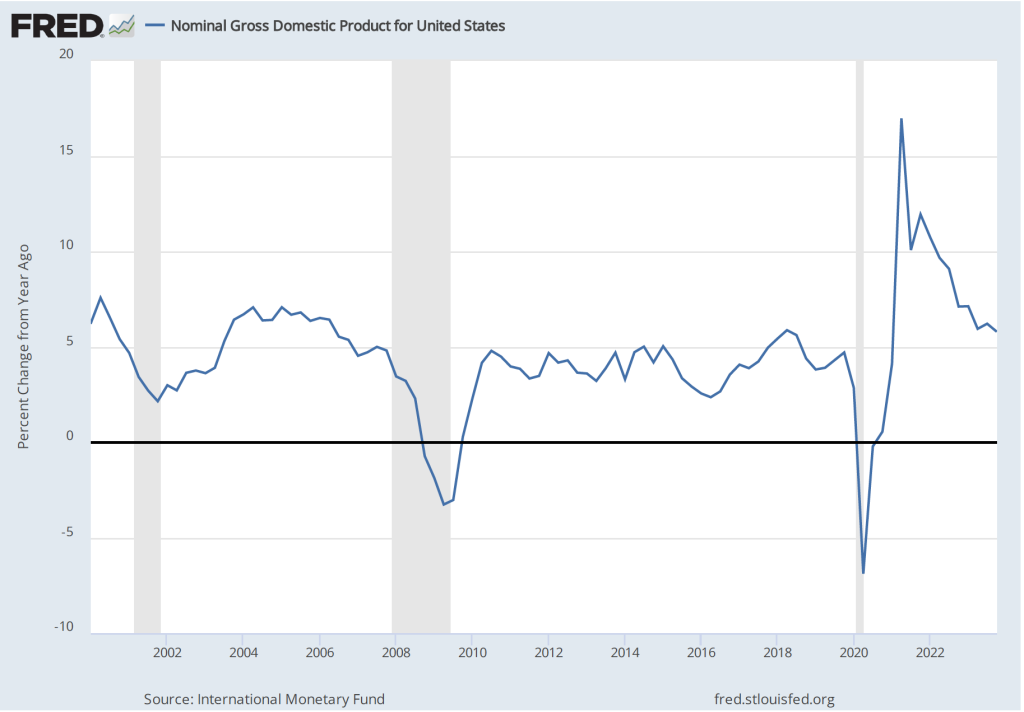

As we discuss in the new 9th edition of Macroeconomics, Chapter 15, Section 15.5 (Economics, Chapter 25, Section 25.5), some economists believe that the FOMC should engage in nominal GDP targeting. They argue that this approach has the best chance of stabilizing the growth rate of real GDP while keeping the inflation rate close to the Fed’s 2 percent target. The following figure shows the economy experienced very high rates of inflation during the period when nominal GDP was increasing at an annual rate of greater than 10 percent and that inflation declined as the rate of nominal GDP growth declined toward 5 percent, which is closer to the growth rates seen during the 2000s. (This figure begins in the first quarter of 2000 to put the high growth rates in nominal GDP of 2021 and 2022 in context.)

Fiscal Policy

As we discuss in the new 9th edition of Macroeconomics, Chapter 15 (Economics, Chapter 25), in response to the Covid pandemic Congress and Presidents Trump and Biden implemented the largest discretionary fiscal policy actions in U.S. history. The resulting increases in spending are reflected in the two spikes in federal government expenditures shown in the following figure.

The initial fiscal policy actions resulted in an extraordinary increase in federal expenditures of $3.69 trillion, or 81.3 percent, from the first quarter to the second quarter of 2020. This was followed by an increase in federal expenditures of $2.31 trillion, or 39.4 percent, from the fourth quarter of 2020 to the first quarter of 2021. As we recount in the text, there was a lively debate among economists about whether these increases in spending were necessary to offest the negative economic effects of the pandemic or whether they were greater than what was needed and contributed substantially to the sharp increase in inflation that began in the spring of 2021.

Saving

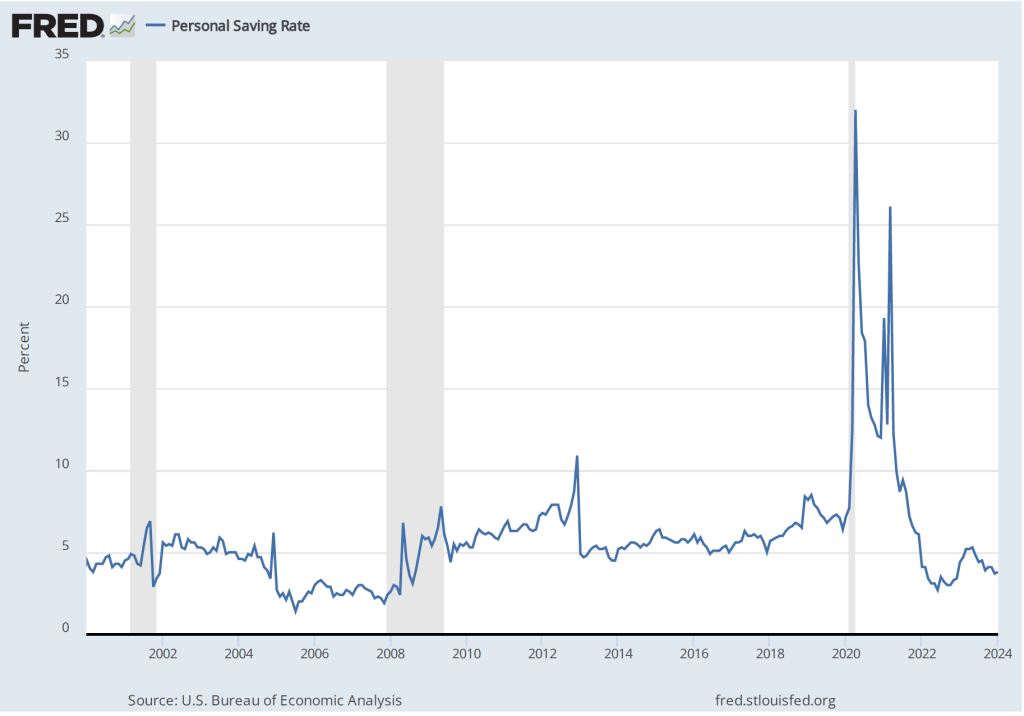

As a result of the fiscal policy actions of 2020 and 2021, many households received checks from the federal government. In total, the federal government distributed about $80o billion directly to households. As the figure shows, one result was to markedly increase the personal saving rate—measured as personal saving as a percentage of disposable personal income—from 6.4 percent in December 2019 to 22.0 in April 2020. (The figure begins in January 2020 to put the size of the spike in the saving rate in perspective.)

The rise in the saving rate helped households maintain high levels of consumption spending, particularly on consumer durables such as automobiles. The first of the following figure shows real personal consumption expenditures and the second figure shows real personal consumption expenditures on durable goods.

Taken together, these data provide an overview of the momentous macroeconomic events of the past four years.

Will the United States Experience a Sustained Boom in the Growth Rate of Labor Productivity?

Blue Planet Studio/Shutterstock

Recent articles in the business press have discussed the possibility that the U.S. economy is entering a period of higher growth in labor productivity:

“Fed’s Goolsbee Says Strong Hiring Hints at Productivity Growth Burst” (link)

“US Productivity Is on the Upswing Again. Will AI Supercharge It?” (link)

“Can America Turn a Productivity Boomlet Into a Boom?” (link)

In Macroeconomics, Chapter 16, Section 16.7 (Economics, Chapter 26, Section 26.7), we highlighted the role of growth in labor productivity in explaining the growth rate of real GDP using the following equations. First, an identity:

Real GDP = Number of hours worked x (Real GDP/Number of hours worked),

where (Real GDP/Number of hours worked) is labor productivity.

And because an equation in which variables are multiplied together is equal to an equation in which the growth rates of these variables are added together, we have:

Growth rate of real GDP = Growth rate of hours worked + Growth rate of labor productivity

From 1950 to 2023, real GDP grew at annual average rate of 3.1 percent. In recent years, real GDP has been growing more slowly. For example, it grew at a rate of only 2.0 percent from 2000 to 2023. In February 2024, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) forecasts that real GDP would grow at 2.0 percent from 2024 to 2034. Although the difference between a growth rate of 3.1 percent and a growth rate of 2.0 percent may seem small, if real GDP were to return to growing at 3.1 percent per year, it would be $3.3 trillion larger in 2034 than if it grows at 2.0 percent per year. The additional $3.3 trillion in real GDP would result in higher incomes for U.S. residents and would make it easier for the federal government to reduce the size of the federal budget deficit and to better fund programs such as Social Security and Medicare. (We discuss the issues concerning the federal government’s budget deficit in this earlier blog post.)

Why has growth in real GDP slowed from a 3.1 percent rate to a 2.0 percent rate? The two expressions on the right-hand side of the equation for growth in real GDP—the growth in hours worked and the growth in labor productivity—have both slowed. Slowing population growth and a decline in the average number of hours worked per worker have resulted in the growth rate of hours worked to slow substantially from a rate of 2.0 percent per year from 1950 to 2023 to a forecast rate of only 0.4 percent per year from 2024 to 2034.

Falling birthrates explains most of the decline in population growth. Although lower birthrates have been partially offset by higher levels of immigration in recent years, it seems unlikely that birthrates will increase much even in the long run and levels of immigration also seem unlikely to increase substantially in the future. Therefore, for the growth rate of real GDP to increase significantly requires increases in the rate of growth of labor productivity.

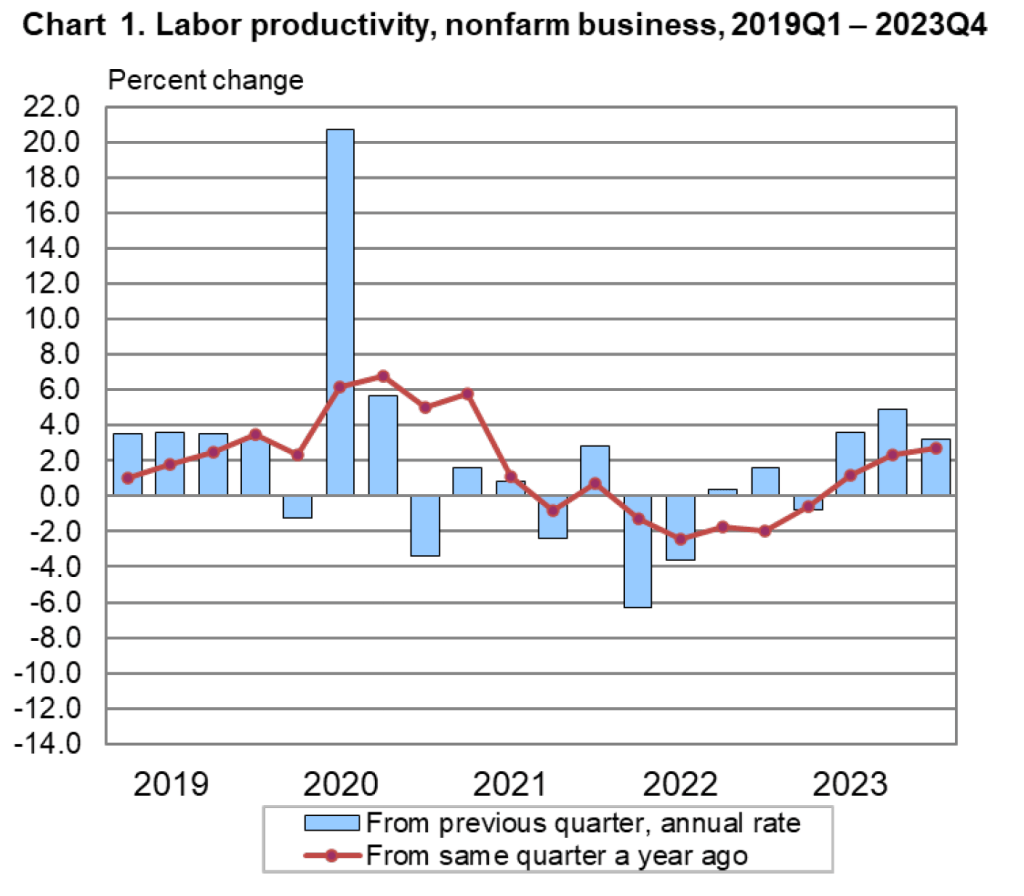

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) publishes quarterly data on labor productivity. (Note that the BLS series is for labor productivity in the nonfarm business sector rather than for the whole economy. Output of the nonfarm business sector excludes output by government, nonprofit businesses, and households. Over long periods, growth in real GDP per hour worked and growth in real output of the nonfarm business sector per hour worked have similar trends.) The following figure is taken from the BLS report “Productivty and Costs,” which was released on February 1, 2024.

Note that the growth in labor productivity increased during the last three quarters of 2023, whether we measure the growth rate as the percentage change from the same quarter in the previous year or as growth in a particular quarter expressed as anual rate. It’s this increase in labor productivity during 2023 that has led to speculation that labor productivity might be entering a period of higher growth. The following figure shows labor productivity growth, measured as the percentage change from the same quarter in the previous year for the whole period from 1950 to 2023.

The figure indicates that labor productivity has fluctuated substantially over this period. We can note, in particular, productivity growth during two periods: First, from 2011 to 2018, labor productivity grew at the very slow rate of 0.9 percent per year. Some of this slowdown reflected the slow recovery of the U.S. economy from the Great Recession of 2007-2009, but the slowdown persisted long enough to cause concern that the U.S. economy might be entering a period of stagnation or very slow growth.

Second, from 2019 through 2023, labor productivity went through very large swings. Labor productivity experienced strong growth during 2019, then, as the Covid-19 pandemic began affecting the U.S. economy, labor productivity soared through the first half of 2021 before declining for five consecutive quarters from the first quarter of 2022 through the first quarter of 2023—the first time productivity had fallen for that long a period since the BLS first began collecting the data. Although these swings were particularly large, the figure shows that during and in the immediate aftermath of recessions labor productivity typically fluctuates dramatically. The reason for the fluctuations is that firms can be slow to lay workers off at the beginning of a recession—which causes labor productivity to fall—and slow to hire workers back during the beginning of an economy recovery—which causes labor productivity to rise.

Does the recent increase in labor productivity growth represent a trend? Labor productivity, measured as the percentage change since the same quarter in the previous year, was 2.7 percent during the fourth quarter of 2023—higher than in any quarter since the first quarter of 2021. Measured as the percentage change from the previous quarter at an annual rate, labor productivity grew at a very high average rate of 3.9 during the last three quarters of 2023. It’s this high rate that some observers are pointing to when they wonder whether growth in labor productivity is on an upward trend.

As with any other economic data, you should use caution in interpreting changes in labor productivity over a short period. The productivity data may be subject to large revisions as the two underlying series—real output and hours worked—are revised in coming months. In addition, it’s not clear why the growth rate of labor productivity would be increasing in the long run. The most common reasons advanced are: 1) the productivity gains from the increase in the number of people working from home since the pandemic, 2) businesses’ increased use of artificial intelligence (AI), and 3) potential efficiencies that businesses discovered as they were forced to operate with a shortage of workers during and after the pandemic.

To this point it’s difficult to evaluate the long-run effects of any of these factors. Wconomists and business managers haven’t yet reached a consensus on whether working from home increases or decreases productivity. (The debate is summarized in this National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, written by Jose Maria Barrero of Instituto Tecnologico Autonomo de Mexico, and Steven Davis and Nicholas Bloom of Stanford. You may need to access the paper through your university library.)

Many economists believe that AI is a general purpose technology (GPT), which means that it may have broad effects throughout the economy. But to this point, AI hasn’t been adopted widely enough to be a plausible cause of an increase in labor productivity. In addition, as Erik Brynjolfsson and Daniel Rock of MIT and Chad Syverson of the University of Chicago argue in this paper, the introduction of a GPT may initially cause productivity to fall as firms attempt to use an unfamiliar technology. The third reason—efficiency gains resulting from the pandemic—is to this point mainly anecdotal. There are many cases of businesses that discovered efficiencies during and immediately after Covid as they struggled to operate with a smaller workforce, but we don’t yet know whether these cases are sufficiently common to have had a noticeable effect on labor productivity.

So, we’re left with the conclusion that if the high labor productivity growth rates of 2023 can be maintained, the growth rate of real GDP will correspondingly increase more than most economists are expecting. But it’s too early to know whether recent high rates of labor productivty growth are sustainable.

Glenn’s Presentation at the ASSA Session on “The U.S. Economy: Growth, Stagnation or Financial Crisis and Recession?”

Glenn participated in this session hosted by the Society of Policy Modeling and the American Economic Association of Economic Educators and moderated by Dominick Salvatore of Fordham University. (Link to the page for this session in the ASSA program.)

Also making presentations at the session were Robert Barro of Harvard University, Janice Eberly of Northwestern University, Kenneth Rogoff of Harvard University, and John Taylor of Stanford University.

Here is the abstract for Glenn’s presentation:

Economic growth is foundational for living standards and as an objective for economic policy. The emergence of Artificial Intelligence as a General Purpose Technology, on the one hand, and a number of demographic and budget challenges, on the other hand, generate an unusually wide range of future economic outcomes. I focus on key ‘policy’ and ‘political economy’ considerations that increase the likelihood of a more favorable growth path given pre-existing trends and technological possibilities. By ‘policy,’ I consider mechanisms enabling growth through research, taxation, the scope of regulation, and competition. By ‘political economy’ factors, I consider mechanisms to increase economic participation in support of growth and policies that enhance it. I argue that both sets of mechanisms are necessary for a viable pro-growth economic policy framework.

These slides from the presentation highlight some of Glenn’s key points. (Note the cover of the new 9th edition of the textbook in slide 7!)

The Roman Emperor Vespasian Fell Prey to the Lump-of-Labor Fallacy

Bust of the Roman Emperor Vespasian. (Photo from en.wikipedia.org.)

Some people worry that advances in artificial intelligence (AI), particularly the development of chatbots will permanently reduce the number of jobs available in the United States. Technological change is often disruptive, eliminating jobs and sometimes whole industries, but it also creates new industries and new jobs. For example, the development of mass-produced, low-priced automobiles in the early 1900s wiped out many jobs dependent on horse-drawn transportation, including wagon building and blacksmithing. But automobiles created many new jobs not only on automobile assembly lines, but in related industries, including repair shops and gas stations.

Over the long run, total employment in the United States has increased steadily with population growth, indicating that technological change doesn’t decrease the total amount of jobs available. As we discuss in Microeconomics, Chapter 16 (also Economics, Chapter 16), fears that firms will permanently reduce their demand for labor as they increase their use of the capital that embodies technological breakthroughs, date back at least to the late 1700s in England, when textile workers known as Luddites—after their leader Ned Ludd—smashed machinery in an attempt to save their jobs. Since that time, the term Luddite has described people who oppose firms increasing their use of machinery and other capital because they fear the increases will result in permanent job losses.

Economists believe that these fears often stem from the lump-of-labor fallacy, which holds that there is only a fixed amount of work to be performed in the economy. So the more work that machines perform, the less work that will be available for people to perform. As we’ve noted, though, machines are substitutes for labor in some uses—such as when chatbot software replace employees who currently write technical manuals or computer code—they are also complements to labor in other jobs—such as advising firms on how best to use chatbots.

The lump-of-labor fallacy has a long history, probably because it seems like common sense to many people who see the existing jobs that a new technology destroys, without always being aware of the new jobs that the technology creates. There are historical examples of the lump-of-labor fallacy that predate even the original Luddites.

For instance, in his new book Pax: War and Peace in Rome’s Golden Age, the British historian Tom Holland (not to be confused with the actor of the same name, best known for portraying Spider-Man!), discusses an account by the ancient historian Suetonius of an event during the reign of Vespasian who was Roman emperor from 79 A.D. to 89 A.D. (p. 201):

“An engineer, so it was claimed, had invented a device that would enable columns to be transported to the summit of the [Roman] Capitol at minimal cost; but Vespasian, although intrigued by the invention, refused to employ it. His explanation was a telling one. ‘I have a duty to keep the masses fed.’”

Vespasian had fallen prey to the lump-of-labor fallacy by assuming that eliminating some of the jobs hauling construction materials would reduce the total number of jobs available in Rome. As a result, it would be harder for Roman workers to earn the income required to feed themselves.

Note that, as we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapters 10 and 11 (also Economics, Chapter 20 and 21), over the long-run, in any economy technological change is the main source of rising incomes. Technological change increases the productivity of workers and the only way for the average worker to consume more output is for the average worker to produce more output. In other words, most economists agree that the main reason that the wages—and, therefore, the standard of living—of the average worker today are much higher than they were in the past is that workers today are much more productive because they have more and better capital to work with.

Although the Roman Empire controlled most of Southern and Western Europe, the Near East, and North Africa for more than 400 years, the living standard of the average citizen of the Empire was no higher at the end of the Empire than it had been at the beginning. Efforts by emperors such as Vespasian to stifle technological progress may be part of the reason why.

10/21/23 Podcast – Authors Glenn Hubbard & Tony O’Brien reflect on the Fed’s efforts to execute the soft-landing.

Join authors Glenn Hubbard & Tony O’Brien as they reflect on the Fed’s efforts to execute the soft landing, ponder if the effect will stick, and wonder if future economies will be tethered to an anchor point above two percent.

9/16/23 Podcast – Authors Glenn Hubbard & Tony O’Brien discuss inflation, the current status of a soft-landing, and the green economy.

Join authors Glenn Hubbard & Tony O’Brien as they discuss the economic landscape of inflation, soft-landings, and the green economy. This conversation occurred on Saturday, 9/16/23, prior to the FOMC meeting on September 19th-20th.

How Did the United States Reduce the Debt-to-GDP Ratio after World War II?

Main Gun Mount Assembly Plant, Northern Pump Co. Plant, Fridley, Minnesota, 1942. (Photo from the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum.)

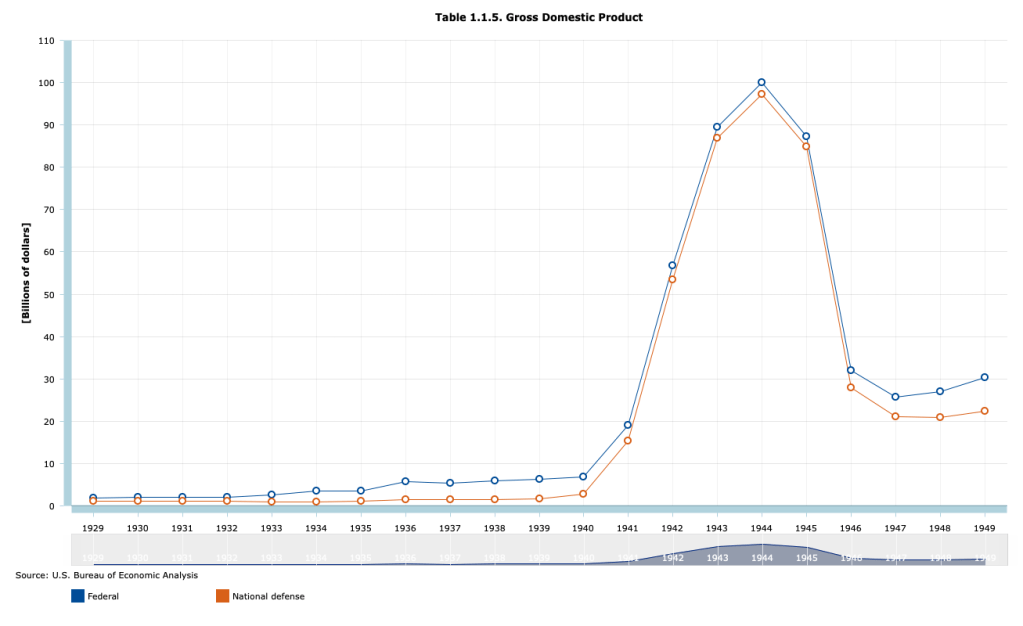

To fight World War II, the federal government had to dramatically increase spending. As the following figure shows, total federal spending rose from $6.8 billion in 1940 to a peak of $100.1 billion in 1944. National defense spending made up most of the increase, rising from $2.8 billion in 1940 to $97.3 billion in 1944.

Part of the increased spending was paid for by increases in taxes. Total federal tax receipts rose from $6.2 billion in 1940 to $35.8 billion in 1945. Individual income taxes rose from $1.0 billion in 1940 to 18.6 billion in 1945. Tax rates were raised and the minimum income at which people had to pay tax on their income was reduced. From the introduction of the federal individual income tax in 1913 until 1940, only people who had at least upper middle class incomes paid any federal income taxes. Following the passage by Congress of the Revenue Act of 1942, most workers had to pay federal income taxes. In 1940, 7.4 million people had to pay federal individual income taxes. In 1945, 42.7 million people had to. For the first time, the federal government withheld taxes from workers paychecks. Previously, all taxes were due on March 15th of the year following the year being taxed. Milton Friedman, who in the 1970s won the Nobel Prize in Economics, was part of the team at the U.S. Treasury that designed and implemented the system of withholding income taxes. Withholding of individual income taxes has continued to the present day.

Although large, the increases in federal taxes were insufficient to fund the massive military spending required to win the war. As a result, the U.S. Treasury had to greatly increase its sales of Treasury bonds. Recall from Macroeconomics, Chapter 16, Section 16.6 (Economics, Chapter 26, Section 26.6 and Essentials of Economics, Chapter 18, Section 18.6) that the total value of outstanding Treasury bonds is called the federal government debt, sometimes called the national debt. The part of federal government debt held by the public rather than by government agencies, such as the Social Security Trust Funds, is call the public debt. In order to gauge the effects of the debt on the economy, economists typically look at the size of the public debt relative to GDP. The following figure shows the public debt as a percentage of GDP for the years from 1929 to 2022.

The figure shows that the ratio of debt to GDP increased sharply from 1929 to the mid-1930s, reflecting the federal budget deficits resulting from the Great Depression, and then soared beginning in 1940. Debt peaked at 113 percent of GDP in 1945 and then began a long decline that lasted until 1974, when debt had fallen to 23 percent of GDP. The ratio of debt to GDP then fluctuated until the Great Recession of 2007-2009 when it began a steady increase that turned into a surge during and after the Covid-19 pandemic. (We discuss the causes of the recent surge in debt in this blog post.)

What caused the long decline in the ratio of debt to GDP that began in 1946 and continued until 1974? The usual explanation is that the decline was not primarily due to the federal government paying off a signficiant portion of the debt. The public debt did decline from a peak of $241.9 billion in 1946 to $214.3 billion in 1949 but there were no significant declines in the level of the public debt after 1949. Instead the ratio of debt to GDP declined because GDP grew faster than did the debt.

Recently in a National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, “Did the U.S. Really Grow Out of Its World War II Debt?” Julien Acalin and Laurence M. Ball of Johns Hopkins University have analyzed the issue more closely. They conclude that economic growth played a smaller role in reducing the debt-to-GDP ratio than has previously been thought. In particular, they highlight the fact that for significant periods through the 1970s, the Treasury was able to pay a real interest rate on the debt that was lower than market rates. Lower real interest rates reduced the amount by which the debt might otherwise have grown.

As we discuss in Money, Banking, and the Financial System, Chapter 13, Section 13.2, in April 1942, to support the war effort, the Federal Reserve announced that it would fix interest rates on Treasury securities at low levels: 0.375 percent on Treasury bills and 2.5 percent on Tresaury bonds. This policy continued after the end of the war in 1945 until the Fed was allowed to abandon the policy of pegging the interest rates on Treasury securities following the March 1951 Treasury-Federal Reserve Accord. Acalin and Ball also note that even after the Accord, there were periods in which actual inflation was well above expected inflation, causing the real interest rate the Treasury was paying on debt to be below the expected real interest rate. In other words, part of the falling debt-to-GDP ratio was financed by investors receiving lower returns on their purchases of Treasury securities than they had expected to.

Acalin and Ball conclude that if the Treasury had not done the relatively small amount of debt repayment mentioned earlier and if it had had to pay market real interest rates on the debt, debt would have declined to only 74 percent of GDP in 1974, rather than to 23 percent.

Sources: The debt and GDP data are from the Congressional Budget Office, which can be found here, and from the Office of Management and the Budget, which can be found here.

4/29/23 Podcast – Authors Glenn Hubbard & Tony O’Brien discuss a hard vs. soft landing, the debt ceiling, and an economics view of the CHIPS act passed in 2022.

Join authors Glenn Hubbard & Tony O’Brien as they discuss the state of the landing the economy will achieve – hard vs. soft – or “no landing”. Also, they address the debt ceiling and the barriers it might present to a recovery. We also delve into the Chips Act and what economics has to say about the subsidy of a particular industry. Gain insights into today’s economy through our final podcast of the 2022-2023 academic year! Our discussion covers these points but you can also check for updates on our blog post that can be found HERE .

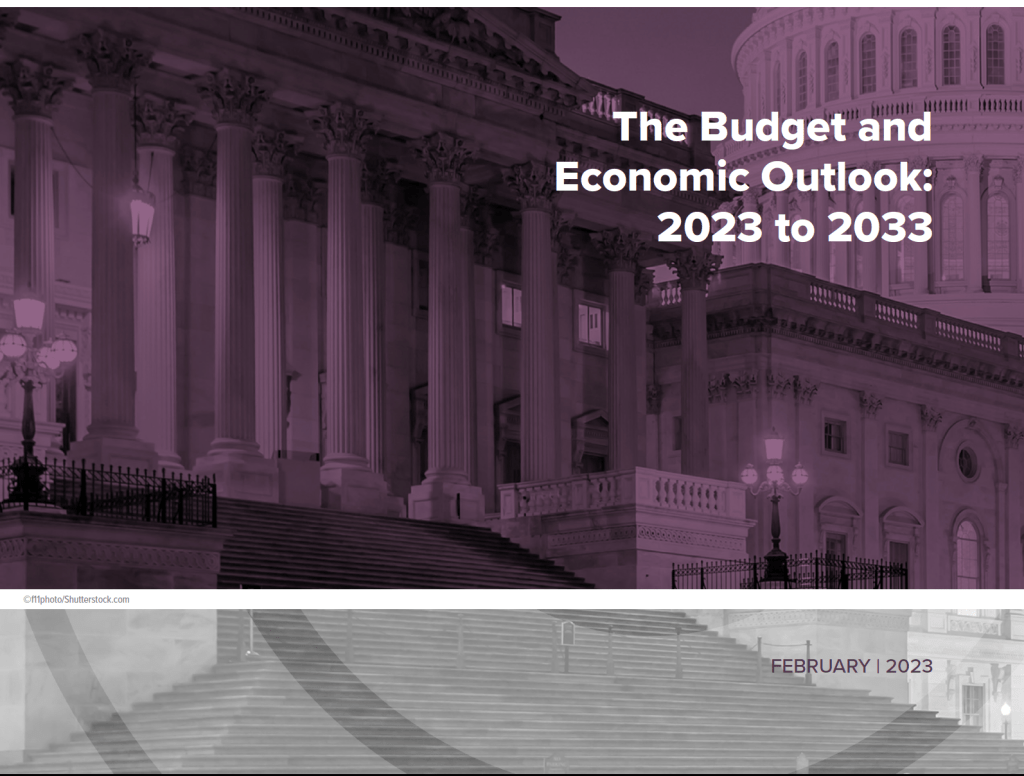

Bad News from the Congressional Budget Office

In 1974, Congress created the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). The CBO was given the responsibility of providing Congress with impartial economic analysis as it makes decisions about the federal government’s budget. One of the most widely discussed reports the CBO issues is the Budget and Economic Outlook. The report provides forecasts of future federal budget deficits and changes in the federal government’s debt that the budget deficits will cause. The CBO’s budget and debt forecasts rely on the agency’s forecasts of future economic conditions and assumes that Congress will make no changes to current laws regarding taxing and spending. (We discuss this assumption further below.)

On February 15, the CBO issued its latest forecasts. The forecasts showed a deterioration in the federal government’s financial situation compared with the forecasts the CBO had issued in May 2022. (You can find the full report here.) Last year, the CBO forecast that the federal government’s cumulative budget deficit from 2023 through 2032 would be $15.7 trillion. The CBO is now forecasting the cumulative deficit over the same period will be $18.8 trillion. The three main reason for the increase in the forecast deficits are:

1. Congress has increased spending—particularly on benefits for military veterans.

2) Cost-of-living adjustments for Social Security and other government programs have increased as a result of higher inflation.

3) Interest rates on Treasury debt have increased as a result of higher inflation.

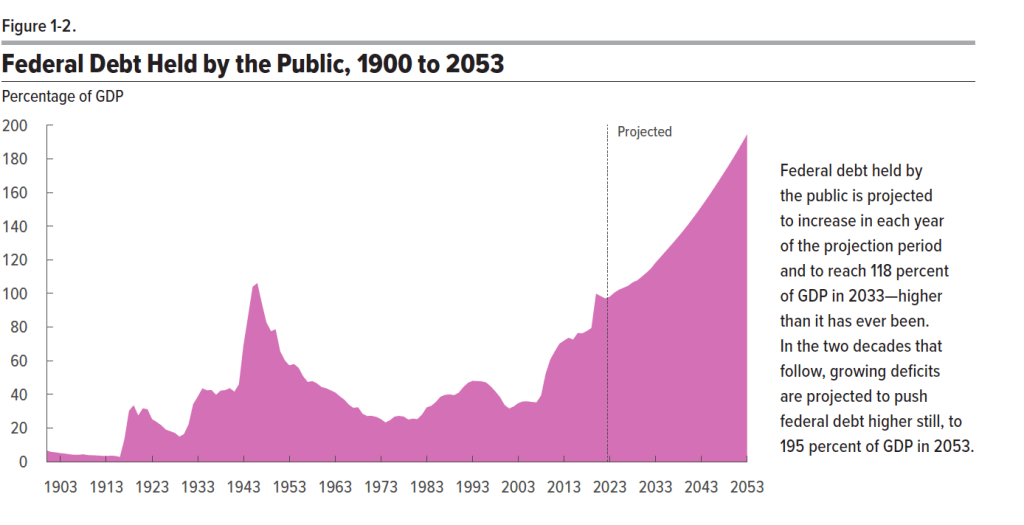

The CBO forecasts that federal debt held by the public will increase from 98 percent of GDP in 2023 to 118 percent in 2033 and eventually to 198 percent in 2053. Note that economists prefer to measure the size of the debt relative to GDP rather than in as absolute dollar amounts for two main reasons: First, measuring debt relative to GDP makes it easier to see how debt has changed over time in relation to the growth of the economy. Second, the size of debt relative to GDP makes it easier to gauge the burden that the debt imposes on the economy. When debt grows more slowly than the economy, as measured by GDP, crowding effects are likely to be relatively small. We discuss crowding out in Macroeconomics, Chapter 10, Section 10.2 and Chapter 16, Section 16. 5 (Economics, Chapter 20, Section 20.2 and Chapter 26, Section 26.5). The two most important factors driving increases in the ratio of debt to GDP are increased spending on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, and increased interest payments on the debt.

The following figure is reproduced from the CBO report. It shows the ratio of debt to GDP with actual values for the period 1900-2022 and projected values for the period 2023-2053. Note that the only other time the ratio of debt to GDP rose above 100 percent was in 1945 and 1946 as a result of the large increases in federal government spending required to fight World War II.

The increased deficits and debt over the next 10 years are being driven by government spending increasing as a percentage of GDP, while government revenues (which are mainly taxes) are roughly stable as a percentage of GDP. The following figure from the report shows actual federal outlays and revenues as a percentage of GDP for the period 1973-2022 and projected outlays and revenues for the period 2023-2033. Note that from 1973 to 2022, outlays averaged 21.0 percent of GDP and revenues averaged 17.4 percent of GDP, resulting in an average deficit of 3.6 percent of GDP. By 2033, outlays are forecast to rise to 24.9 percent of GDP–well above the 1973-2022 average–whereas revenues are forecast to be only 18.1 percent, for a forecast deficit of 6.8 percent of GDP.

The increase in outlays is driven primarily by increases in mandatory spending, mainly spending on Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and veterans’ benefits and increases in interest payments on the debt. The CBO’s forecast assumes that discretionary spending will gradually decline over the next 10 years as percentage of GDP. Discretionary spending includes federal spending on defense and all other government programs apart from those, like Social Security, where spending is mandated by law.

To avoid the persistent deficits, and increasing debt that results, Congress would need to do one (or a combination) of the following:

1. Reduce the currently scheduled increases in mandatory spending (in political discussions this alternative is referred to as entitlement reform because entitlements is another name for manadatory spending).

2. Decrease discretionary spending, the largest component of which is defense spending.

3. Increases taxes.

There doesn’t appear to be majority support in Congress for taking any of these steps.

The CBO’s latest forecast seems gloomy, but may actually understate the likely future increases in the federal budget deficit and federal debt. The CBO’s forecast assumes that future outlays and taxes will occur as indicated in current law. For example, the forecast assumes that many of the tax cuts Congress passed in 2017 will expire in 2025 as stated in current law. Many political observers doubt that Congress will allow the tax cuts to expire as scheduled because to do so would result in increases in individual income taxes for most people. (Here is a recent article in the Washington Post that discusses this point. A subscription may be required to access the full article.) The CBO also assumes that defense spending will not increase beyond what is indicated by current law. Many political observers believe that, in fact, Congress may feel compelled to substantially increase defense spending as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and the potential military threat posed by China.

The CBO forecast also assumes that the U.S. economy won’t experience a recession between 2023 and 2033, which is possible but unlikely. If the economy does experience a recession, federal outlays for unemployment insurance and other programs will increase and federal personal and corporate income tax revenues will fall. The CBO’s forecast also assumes that the interest rate on the 10-year Treasury note will be under 4 percent and that the federal funds rate will be under 3 percent (interest rates on short-term Treasury debt move closely with changes in the federal funds rate). If interest rates turn out to be higher than these forecasts, the federal government’s interest payments will increase, further increasing the deficit and the debt.

In short, the federal government is clearly facing the most difficult budgetary situation since World War II.