Supports: Microeconomics, Chapter 15, Section 15.6; Economics, Chapter 55, Section 15.6; and Essentials of Economics, Chapter 10, Sections 10.6.

PG&E workers moving a powerline underground. (Photo from the Wall Street Journal.)

PG&E, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas and Electric are public utilities that provide electricity and natural gas to households and firms in California. (For the most part, they provide these services in different parts of the state.) The California Public Utilities Commission regulates the prices that these utilities charge. In March 2024, an article in the San Francisco Chronicle reported that the commission proposed that the utilities begin charging households who receive their electricity from these utilities an additional flat fee of $24 per month (that would not depend on the quantity of electricity a household uses), while reducing the price households pay for each kilowatt hour they use by about 6 cents.

Isn’t this policy contradictory—adding a flat fee to households’ electric bills while reducing the price per kilowatt hour households pay? Can you explain why the policy might make economic sense? Draw a graph showing the situation of a public utility to illustrate your answer.

Solving the Problem

Step 1: Review the chapter material. This problem is about how the government regulates public utilities, so you may want to review the section in Microeconomics, Chapter 15, Section 15.6, on “Regulating Natural Monopolies,” (Economics, Chapter 15, Section 15.6 and Essentials of Economics, Chapter 10, Section 10.6).

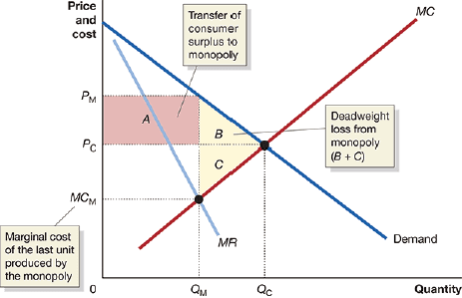

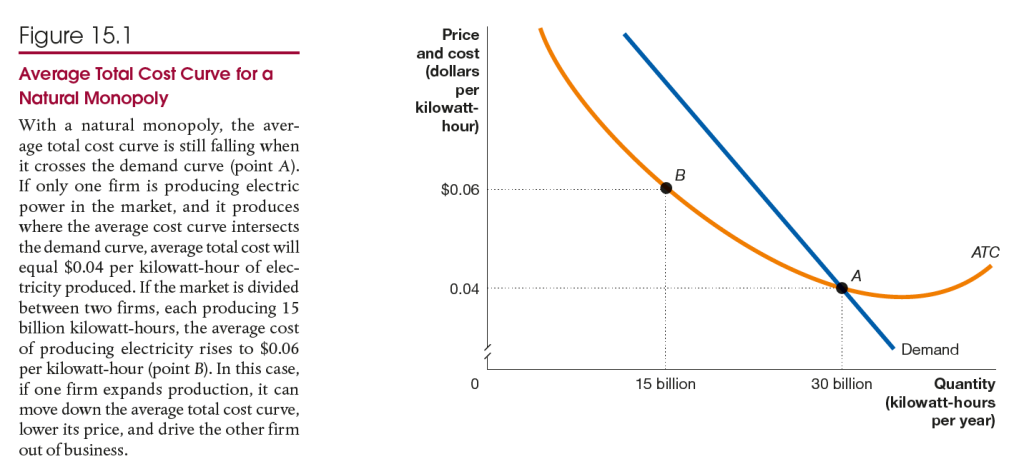

Step 2: Explain why the policy isn’t contradictory and why it might make economic sense. It may seem as if the commission is being contradictory in imposing a new flat rate fee on households while at the same time lowering the price they pay per kilowatt hour used. But, as we discuss in Chapter 15, public utilities are typically natural monoplies because economies of scale are so large in that industy that one firm can supply the electricity in a market at a lower average cost than can two or more firms. Figure 15.1, reproduced below, shows this situation.

As we discuss in the “Regulating Monopoly” section of Chapter 15, Section 15.6, as a result of the large economies of scale in generating electricity, at the quantity at which the marginal cost curve crosses the demand curve, the marginal cost curve is below the demand curve. The economically efficient price is the price equal to the marginal cost of generating electricity. But if the public utility commission requires the utility to charge this price, the utility will suffer losses because it will not be covering its average total cost. The combination of charging households a flat fee while lowering the price they pay per kilowatt hour can help overcome this problem.

Step 3: Finishing solving the problem by drawing a graph to illustrate your answer. You should draw graph similar to Figure 18.8, which we reproduce below. In this graph, if the utility is required to charge the economically efficient price, PE, it will suffer a loss equal to red rectangle. As a result, public utility commissions often set the price of electricity equal to PR, but at that price households demand the quantity of electricity, QR, which is less than the economically efficient quantity, QE. Note, though, that if a public utility commission allows a utillity to collect a flat fee from households equal to the amount shown by the red rectangle, it can require the utility to charge the economically efficient price, PE.

The key point here is that, because it doesn’t change as the quantity of electricity generated and used changes, the flat fee doesn’t affect either the utility’s marginal cost of generating electricity or the cost to households of using another kilowatt of electricity.

We don’t know from the discussion in the article whether the flat fee will cover the entire amount of the utilities’ losses or if the new price will be equal to the efficient price. But the policy can still make economic sense if the new price is closer to the efficient price than was the previous price.

Source: Julie Johnson, “California Proposes A $24 Flat Fee on Utility Bills in Exchange for Lower Electricity Prices,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 28, 2024.