One of the key lessons of economics is that competition serves to push firms toward serving the interests of consumers. When existing firms in an industry are making an economic profit, new firms will enter the industry, which increases the quantity of the good produced and lowers the good’s price. Entry is the essential mechanism that drives a competitive market economy towards achieving allocative efficiency—with the mix of goods and services produced matching consumer preferences—and productive efficiency—with goods and services being produced at the lowest possible cost. (We discuss allocative efficiency and productive efficiency in Chapter 1, Section 1.2.)

For entry to occur requires the efforts of entrepreneurs, who constantly search for opportunities to make a profit. (We discuss the role of entrepreneurs in a market economy in Chapter 2, Section 2.3.) Although, not well remembered today, Victor S. Fox was one of the more flamboyant entrepreneurs in U.S. business history. Fox was born in England in 1893 and moved with his family to Massachusetts three years later. As a young man, he started a firm to manufacture women’s clothing. In 1917, with the entry of the United States into World War I, Fox’s firm switched to producing military uniforms. In 1920, after the end of the war, Fox founded Consolidated Maritime Lines to buy from the U.S. government confiscated German and Austrian cargo ships. Fox also purchased a coal mine in Virginia to provide fuel for the ships. This effort ended in bankruptcy.

In 1929, Fox founded Allied Capital Corporation to invest in the stock market. This firm also failed amid accusations that Fox had broken securities laws. (Most of the information on Fox’s early career is from this site, which relies primarily on mentions of Fox in newspapers.) In 1936, Fox founded Fox Feature Syndicate to produce magazines. At that point, very few comic books were being published. That changed in April 1938, when National Allied Publications released Action Comics, featuring Superman—generally considered the first superhero to appear in comic books. Sales of Superman comic books soared and Fox responded by entering the comic book industry, publishing a comic book starring Wonder Man. Wonder Man was an obvious copy of Superman, which led Superman’s publisher to file a lawsuit against Fox for copyright infringement. Fox agreed to stop publishing Wonder Man, but continued to publish comic books starring superheroes who weren’t such obvious copies of Superman.

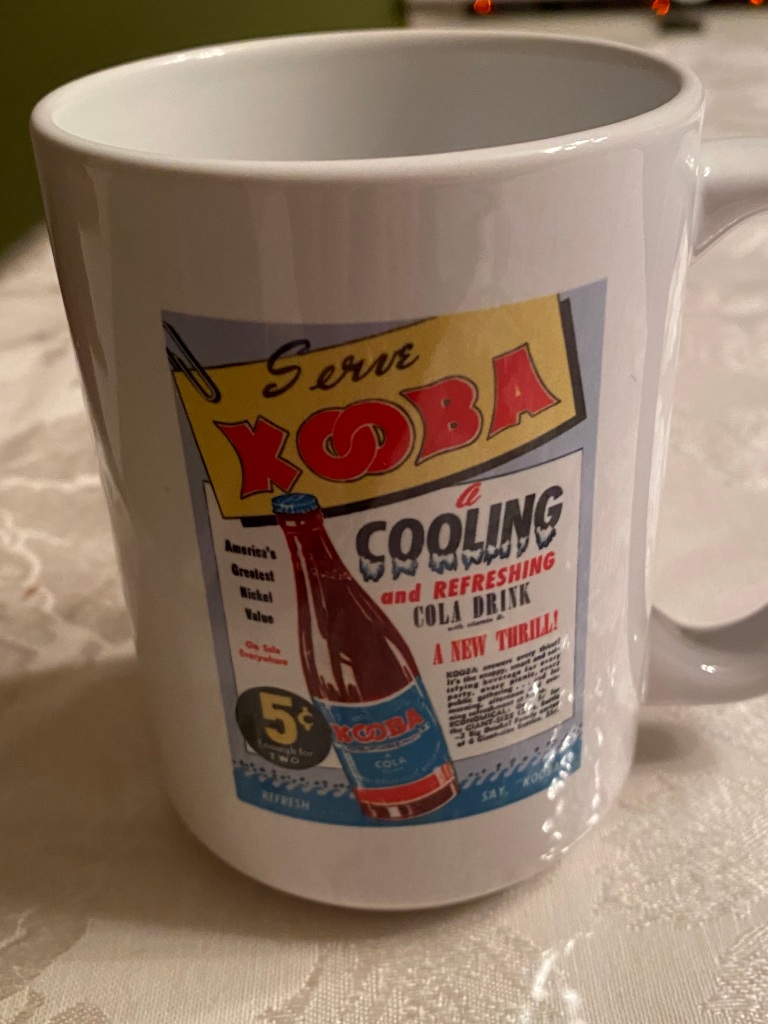

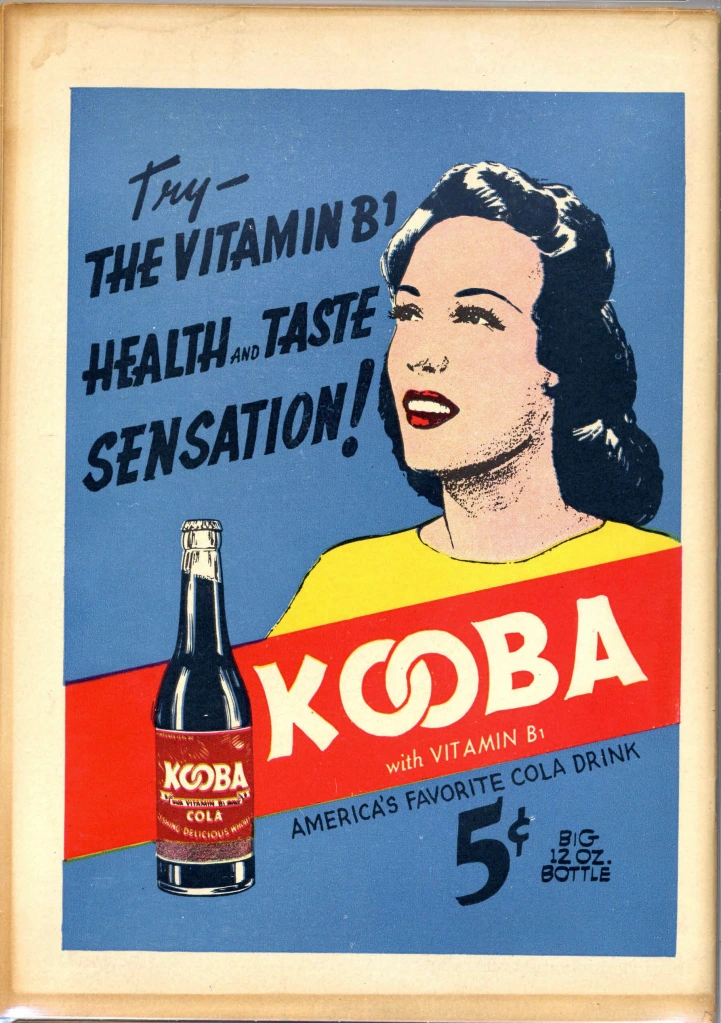

As this summary of Fox’s career indicates, he was an entrepreneur who was willing to enter a new industry whenever he saw a profit opportunity, even if he lacked previous experience in the industry. In 1941, the continuing success of Coca-Cola and Pepsi-Cola led Fox to attempt to enter the cola industry in what was his most audacious entrepreneurial effort. The high sales of his comic books gave Fox a platform to advertise his new soft drink —Kooba cola. The following are some of Fox’s advertisements for Kooba cola.

Fox also advertised Kooba on a radio program featurning the Blue Beetle, one of his comic book superheroes. In the print advertisements for Kooba, Fox seems to have focused on two points in an attempt to differentiate his cola from existing colas, particularly Coke and Pepsi. (We discuss the role product differentiation plays in competition among firms in Microeconomics and Economics, Chapter 13.) First, to help overcome the belief among some consumers that colas were an unhealthy drink, Fox emphasized that Kooba cola would contain vitamin B1. In 1941, vitamin B1 had only recently become available and was the subject of newspaper stories. Second, at 12 ounces, bottles of Kooba were nearly twice as large as the standard 6.5 ounce Coke bottle but would sell for the same 5 cent price. One of the advertisements above notes that a six-pack of Kooba had a price of only 25 cents.

How was Fox able to sell his new cola for about half the price per ounce of Coke or Pepsi? That’s unclear because—amazingly—at the time Fox was running these advertisements, not only was Kooba not “available everywhere,” as the advertisements claimed, it wasn’t available anywhere. Fox was heavily advertising a product that didn’t actually exist.

How did Fox hope to earn a profit selling a nonexistent product? Fox’s strategy was apparently to begin by heavily advertising Kooba in the hopes of sparking a demand for it. He seems to have believed that if enough people were inspired by his advertisements to ask for the cola at grocery stores and newsstands, he could approach an existing soft drink company and offer to license the Kooba name. He seems never to have intended to actually manufacture the cola, relying instead on royalties paid by the soft drink company he hoped to license the name to.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Fox’s strategy failed. To capitalize on Fox’s advertising, a firm licensing the Kooba name would have had to find a way to make a profit despite selling the cola at a price about half the price charged by competitors. Because Fox had no experience in manufacturing colas, he presumably had no advice to give on how production costs could be reduced sufficiently to allow Kooba to be sold at a profit.

Fox engaged in other entrepreneurial efforts before passing away in 1957. Over the years, Fox pursued a number of business strategies, some of which were successful, at least for a time. But his attempt to make a profit by promoting a nonexistent cola ranks among the the most dubious strategies in U.S. business history. A strategy that likely left some consumers puzzled that a cola that appeared in advertisements was never available in store.