In the textbook, we discuss several measures of inflation. In Macroeconomics, Chapter 8, Section 8.4 (Economics, Chapter 18, Section 18.4) we discuss the GDP deflator as a measure of the price level and the percentage change in the GDP deflator as a measure of inflation. In Chapter 9, Section 9.4, we discuss the consumer price index (CPI) as a measure of the price level and the percentage change in the CPI as the most widely used measure of inflation.

In Chapter 15, Section 15.5 we examine the reasons that the Federal Reserve often looks at the core inflation rate—the inflation rate excluding the prices of food and energy—as a better measure of the underlying rate of inflation. Finally, in that section we note that the Fed uses the percentage change in the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index to assess of whether it’s achieving its goal of a 2 percent inflation rate.

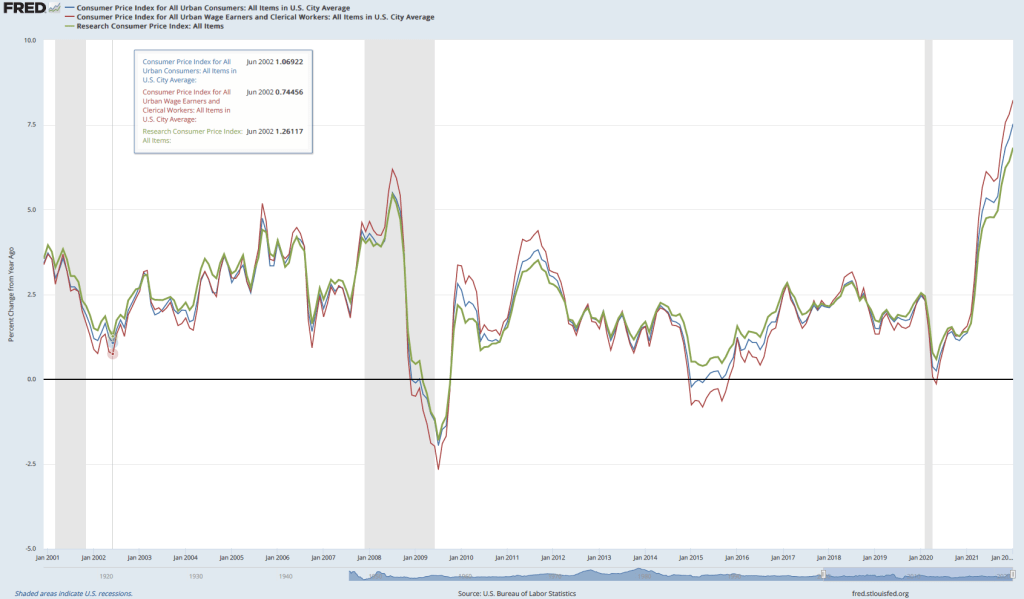

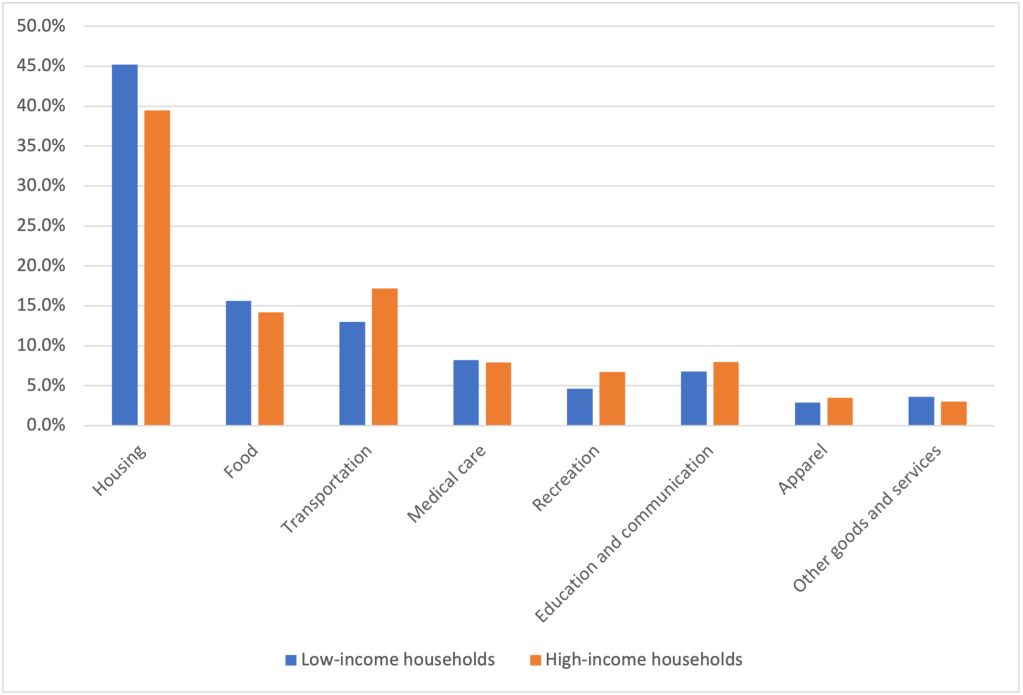

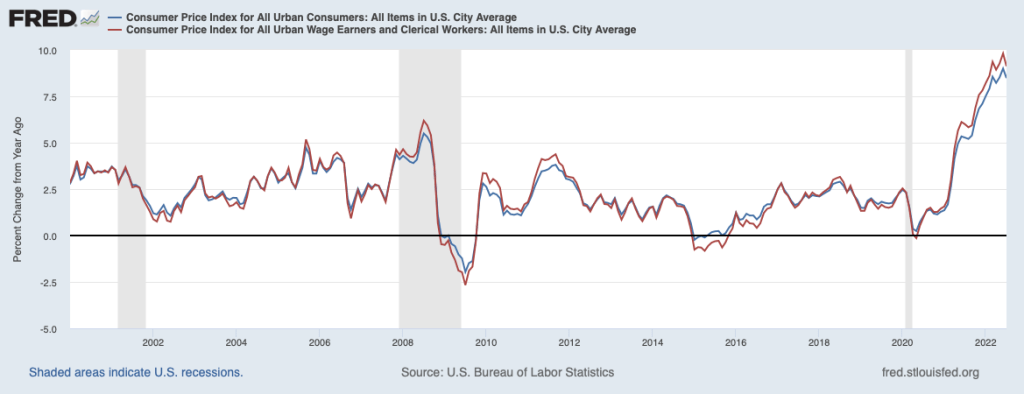

In this blog post, we’ll discuss two other aspects of measuring inflation that we don’t cover in the textbook. First, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) publishes two versions of the CPI: (1) The familiar CPI for all urban consumers (or CPI–U), which includes prices of goods and services purchased by households in urban areas, and (2) the less familiar CPI for urban wage earners and clerical workers (or CPI–W), which includes the same prices included in the CPI–U. The two versions of the CPI give slightly different measures of the inflation rate—despite including the same prices—because each version applies different weights to the prices when constructing the index.

As we explain in Chapter 9, Section 9.4, the weights in the CPI–U (the only version of the CPI we discuss in the chapter) are determined by a survey of 36,000 households nationwide on their spending habits. The more the households surveyed spend on a good or service, the larger the weight the price of the good or service receives in the CPI–U. To calculate the weights in the CPI–W the BLS uses only expenditures by households in which at least half of the household’s income comes from a clerical or wage occupation and in which at least one member of the household has worked 37 or more weeks during the previous year. The BLS estimates that the sample of households used in calculating the CPI–U includes about 93 percent of the population of the United States, while the households included in the CPI–W include only about 29 percent of the population.

Because the percentage of the population covered by the CPI–U is so much larger than the percentage of the population covered by the CPI–W, it’s not surprising that most media coverage of inflation focuses on the CPI–U. As the following figure shows, the measures of inflation from the two versions of the CPI aren’t greatly different, although inflation as measured by the CPI–W—the red line—tends to be higher during economic expansions and lower during economic recessions than inflation measured by the CPI–U—the blue line.

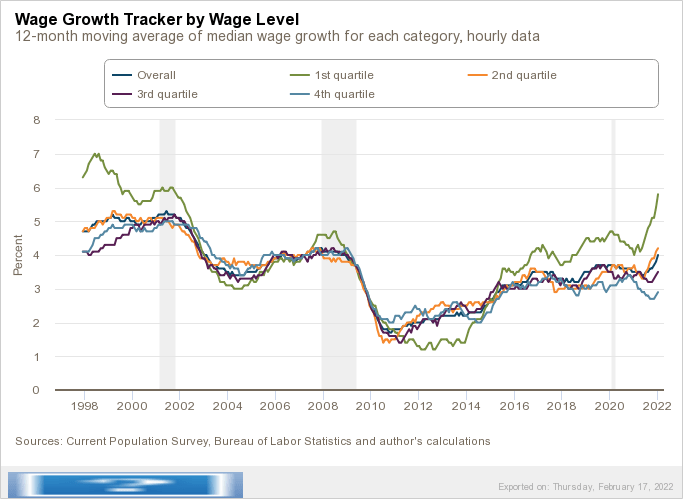

One important use of the CPI–W is in calculating cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) applied to Social Security payments retired and disabled people receive. Each year, the federal government’s Social Security Administration (SSA) calculates the average for the CPI–W during June, July, and August in the current year and in the previous year and then measures the inflation rate as the percentage increase between the two averages. The SSA then increases Social Security payments by that inflation rate. Because the increase in CPI–W is often—although not always—larger than the increase in CPI–U, using CPI–W to calculate Social Security COLAs increases the payments recipients of Social Security receive.

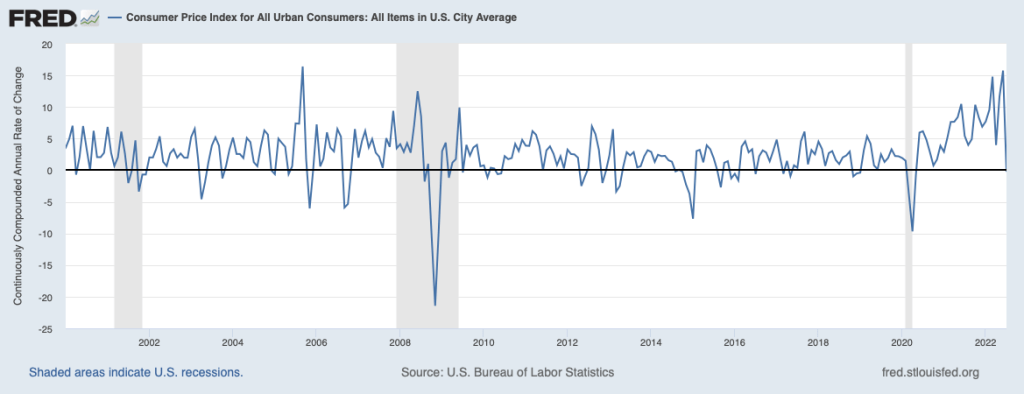

A second aspect of measuring inflation that we don’t mention in the textbook was the subject of discussion following the release of the July 2022 CPI data. In June 2022, the value for the CPI–U was 295.3. In July 2022, the value for the CPI–U was also 295.3. So, was there no inflation during July—an inflation rate of 0 percent? You can certainly make that argument, but typically, as we note in the textbook (for instance, see our display of the inflation rate in Chapter 10, Figure 10.7) we measure the inflation rate in a particular month as the percentage change in the CPI from the same month in the previous year. Using that approach to measuring inflation, the inflation rate in July 2022 was the percentage change in the CPI from its value in July 2021, or 8.5 percent. Note that you could calculate an annual inflation rate using the increase in the CPI from one month to the next by compounding that rate over 12 months. In this case, because the CPI was unchanged from June to July 2022, the inflation rate calculated as a compound annual rate would be 0 percent.

During periods of moderate inflation rates—which includes most of the decades prior to 2021—the difference between inflation calculated in these two ways was typically much smaller. Focusing on just the change in the CPI for one month has the advantage that you are using only the most recent data. But if the CPI in that month turns out to be untypical of what is happening to inflation over a longer period, then focusing on that month can be misleading. Note also that inflation rate calculated as the compound annual change in the CPI each month results in very large fluctuations in the inflation rate, as shown in the following figure.

Sources: Anne Tergesen, “Social Security Benefits Are Heading for the Biggest Increase in 40 Years,” Wall Street Journal, August 10, 2022; Neil Irwin, “Inflation Drops to Zero in July Due to Falling Gas Prices,” axios.com, August 10, 2022; “Consumer Price Index Frequently Asked Questions,” bls.gov, March 23, 2022; Stephen B. Reed and Kenneth J. Stewart, “Why Does BLS Provide Both the CPI–W and CPI–U?” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Beyond the Numbers, Vol. 3, No. 5, February 2014; “Latest Cost of Living Adjustment,” ssa.gov; and Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.