Join authors Glenn Hubbard & Tony O’Brien as they discuss the economic landscape of inflation, soft-landings, and the green economy. This conversation occurred on Saturday, 9/16/23, prior to the FOMC meeting on September 19th-20th.

Tag: Federal Reserve

Inflation, Disinflation, Deflation, and Consumers’ Perceptions of Inflation

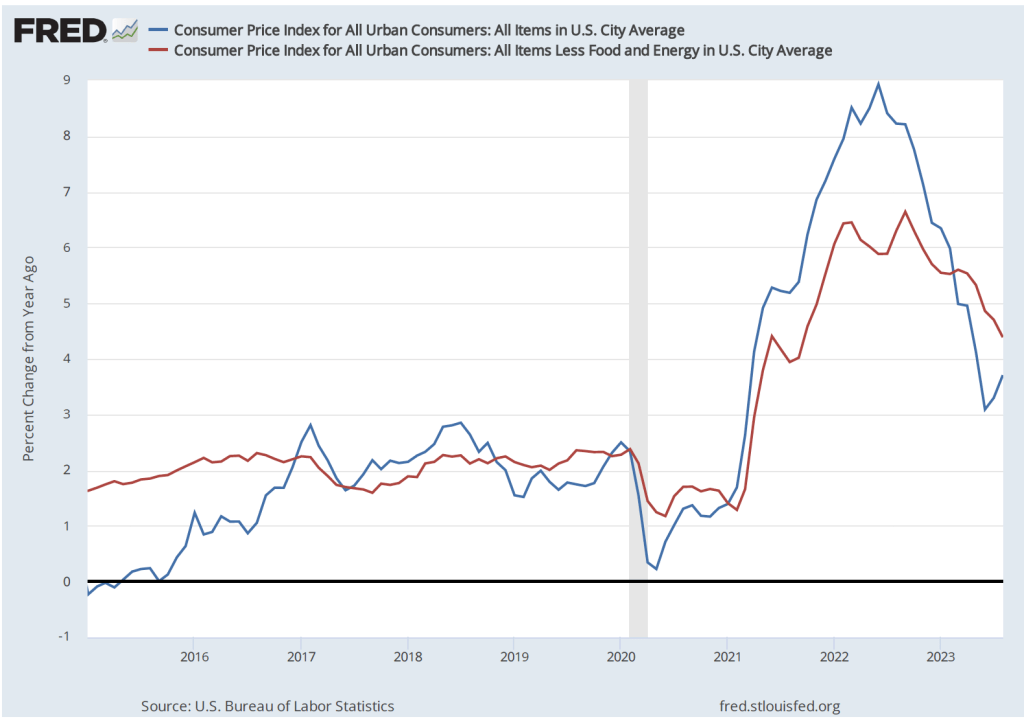

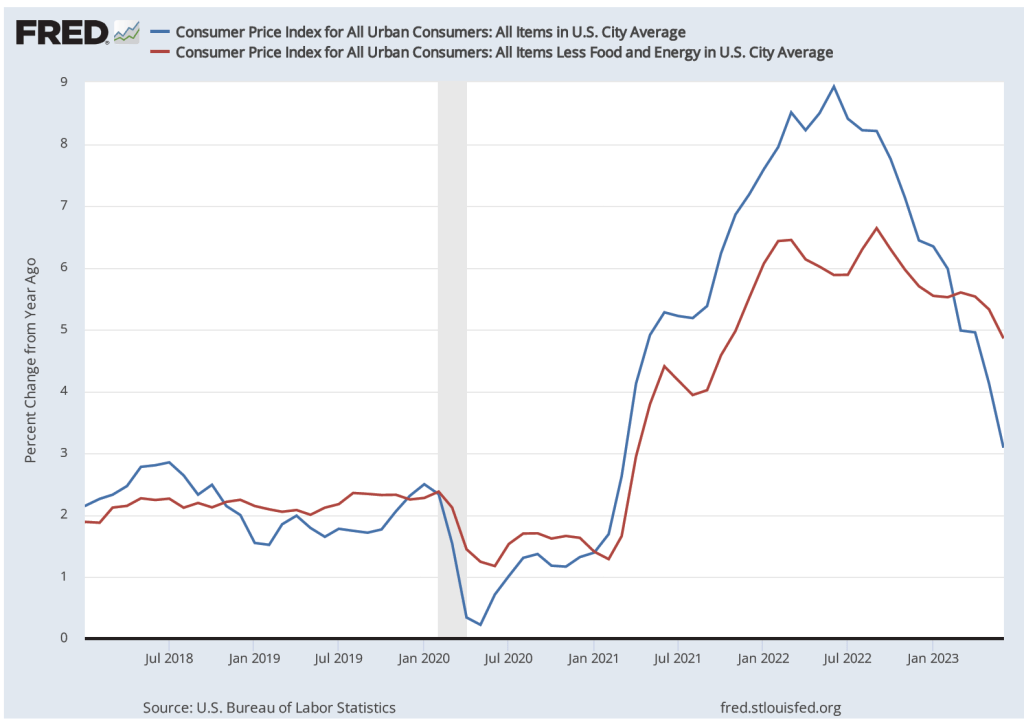

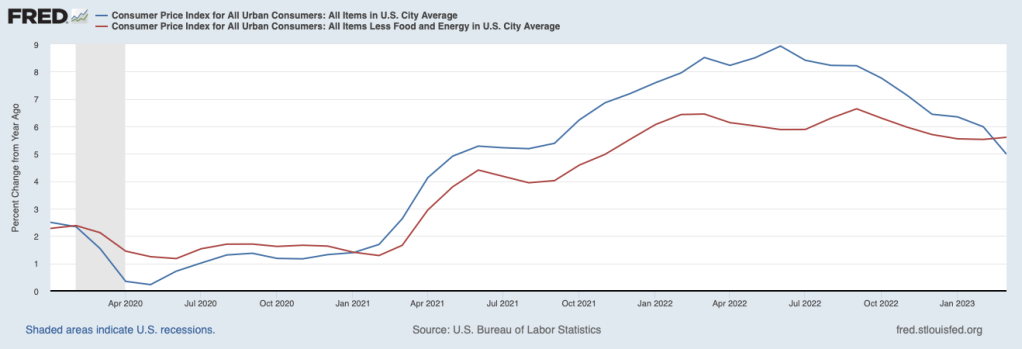

Inflation has declined, although many consumers are skeptical. What explains consumer skepticism? First we can look at what’s happened to inflation in the period since the beginning of 2015. The figure below shows inflation measured as the percentage change in the consumer price index (CPI) from the same month in the previous year. We show both so-called headline inflation, which includes the prices of all goods and services in the index, and core inflation, which excludes energy and food prices. Because energy and food prices can be volatile, most economists believe that the core inflation provides a better indication of underlying inflation.

Both measures show inflation following a similar path. The inflation rate begins increasing rapidly in the spring of 2021, reaches a peak in the summer of 2022, and declines from there. Headline CPI peaks at 8.9 percent in June 2022 and declines to 3.7 percent in August 2023. Core inflation reaches a peak of 6.6 percent in September 2022 and declines to 4.4 percent in August 2022.

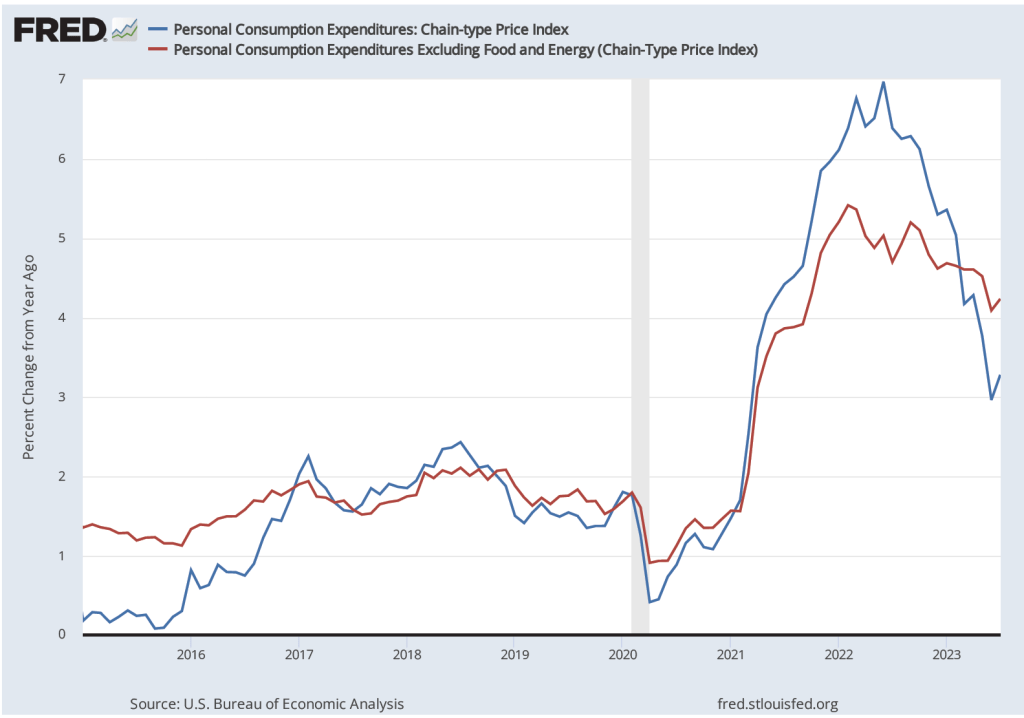

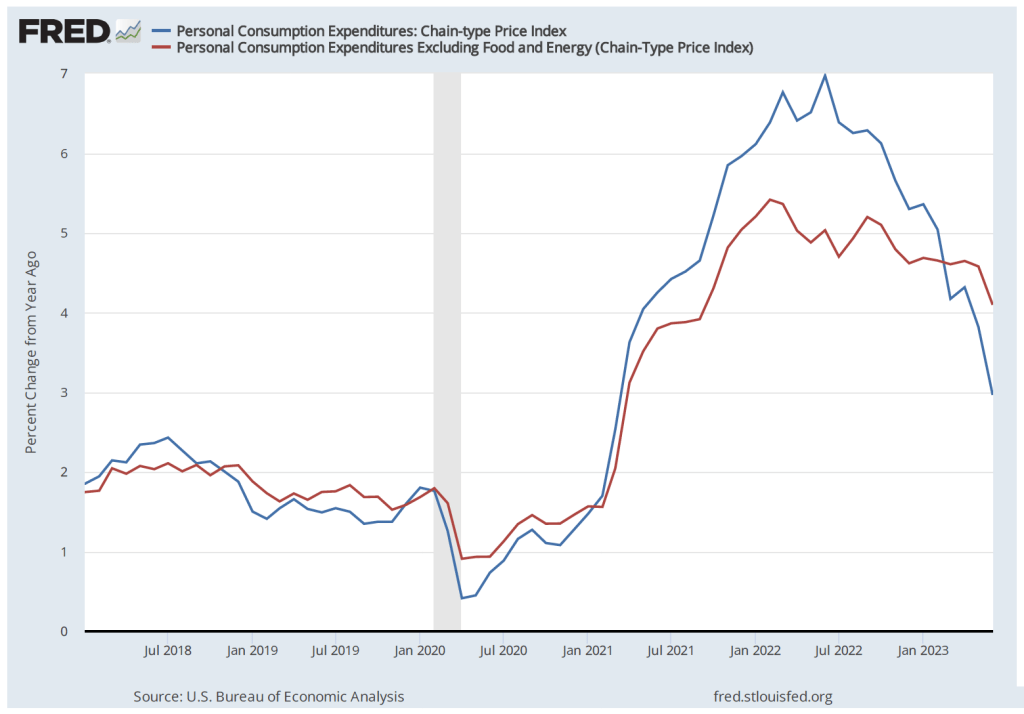

As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 15, Section 15.5 (Economics, Chapter 25, Section 25.5, and Essentials of Economics, Chapter 17, Section 17.5), the Fed’s inflation target is stated in terms of the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) price index, not the CPI. The PCE includes the prices of all the goods and services included in the consumption component of GDP. Because the PCE includes the prices of more goods and services than does the CPI, it’s a broader measure of inflation. The following figure shows inflation as measured by the PCE and by the core PCE, which excludes energy and food prices.

Inflation measured using the PCE or the core PCE shows the same pattern as inflation measured using the CPI: A sharp increase in inflation in the spring of 2021, a peak in the summer of 2022, and a decline thereafter.

Although it has yet to return to the Fed’s 2 percent target, the inflation rate has clearly fallen substantially during the past year. Yet surveys of consumers show that majorities are unconvinced that inflation has been declining. A Pew Research Center poll from June found that 65 percent of respondents believe that inflation is “a very big problem,” with another 27 percent believing that inflation is “a moderately big problem.” A Gallup poll from earlier in the year found that 67 percent of respondents thought that inflation would go up, while only 29 percent thought it would go down. Perhaps not too surprisingly, another Gallup poll found that only 4 percent of respondents had a “great deal” of confidence in Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, with another 32 percent having a “fair amount” of confidence. Fifty-four percent had either “only a little” confidence in Powell or “almost none.”

There are a couple of reasons why most consumers might believe that the Fed is doing worse in its fight against inflation than the data indicate. First, few people follow the data releases as carefully as economists do. As a result, there can be a lag between developments in the economy—such as declining inflation—and when most people realize that the development has occurred.

Probably more important, though, is the fact that most people think of inflation as meaning “high prices” rather than “increasing prices.” Over the past year the U.S. economy has experienced disinflation—a decline in the inflation rate. But as long as the inflation rate is positive, the price level continues to increase. Only deflation—a declining price level—would lead to prices actually falling. And an inflation rate of 3 percent to 4 percent, although considerably lower than the rates in mid-2022, is still significantly higher than the inflation rates of 2 percent or below that prevailed during most of the time since 2008.

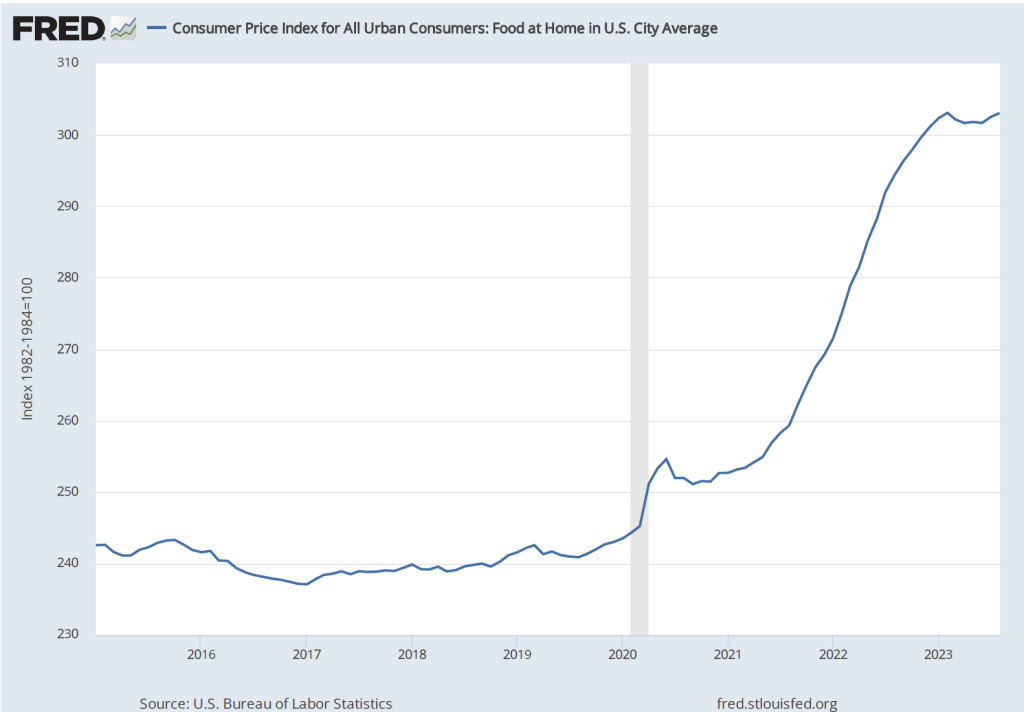

Although, core CPI and core PCE exclude energy and food prices, many consumers judge the state of inflation by what’s happening to gasoline prices and the price of food in supermarkets. These are products that consumers buy frequently, so they are particularly aware of their prices. The figure below shows the component of the CPI that represents the prices of food consumers buy in groceries or supermarkets and prepare at home. The price of food rose rapidly beginning in the spring of 2021. Althought increases in food prices leveled off beginning in early 2023, they were still about 24 percent higher than before the pandemic.

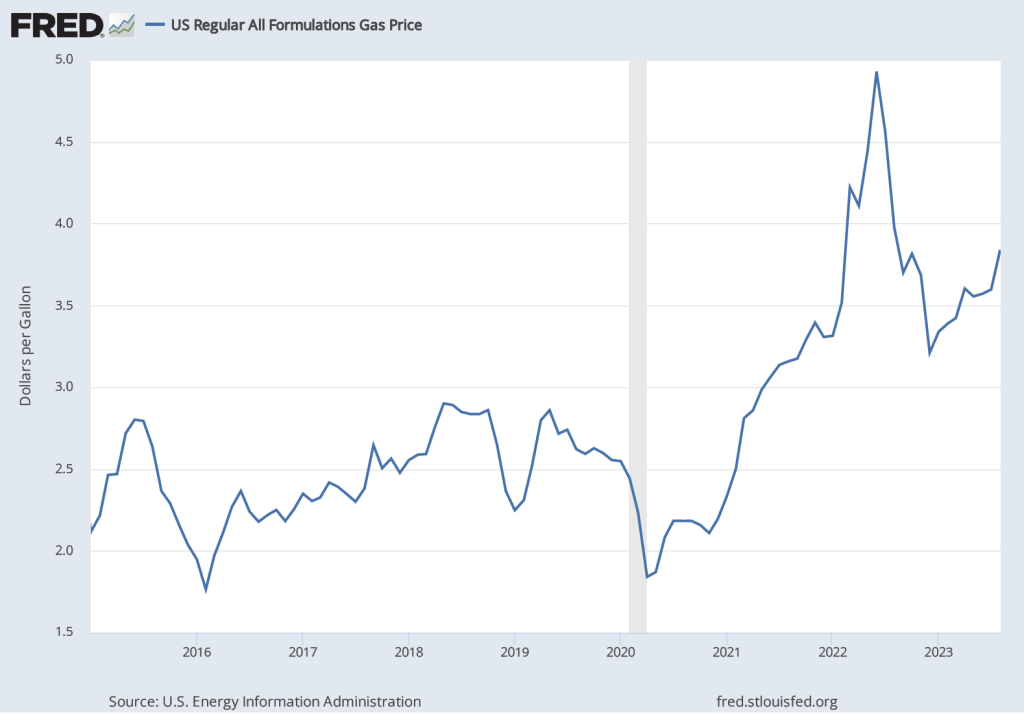

There is a similar story with respect to gasoline prices. Although the average price of gasoline in August 2023 at $3.84 per gallon is well below its peak of nearly $5.00 per gallon in June 2022, it is still well above average gasoline prices in the years leading up to the pandemic.

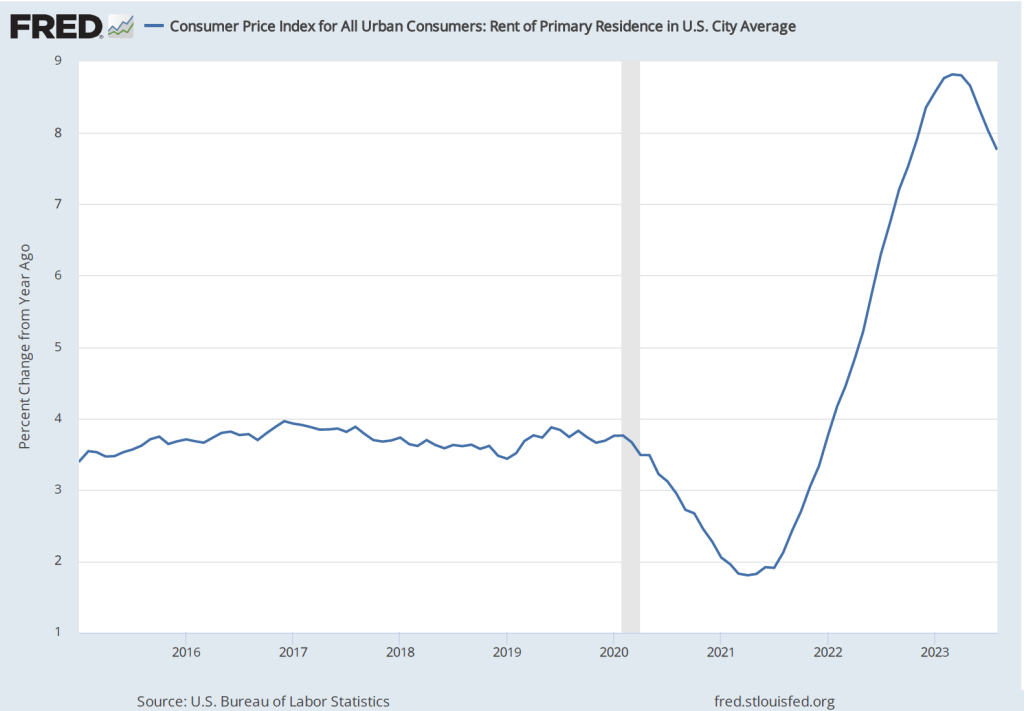

Finally, the figure below shows that while percentage increases in rent are below their peak, they are still well above the increases before and immediately after the recession of 2020. (Note that rents as included in the CPI include all rents, not just rental agreements that were entered into that month. Because many rental agreements, particularly for apartments in urban areas, are for one year or more, in any given month, rents as measured in the CPI may not accurately reflect what is currently happening in rental housing markets.)

Because consumers continue to pay prices that are much higher than the prices they were paying prior to the pandemic, many consider inflation to still be a problem. Which is to say, consumers appear to frequently equate inflation with high prices, even when the inflation rate has markedly declined and prices are increasing more slowly than they were.

What Explains the Surprising Surge in the Federal Budget Deficit?

Figure from CBO’s monthly budget report.

During 2023, GDP and employment have continued to expand. Between the second quarter of 2022 and the second quarter of 2023, nominal GDP increased by 6.1 percent. From July 2022 to July 2023, total employment increased by 3.3 million as measured by the establishment (or payroll) survey and by 3.0 as measured by the household survey. (In this post, we discuss the differences between the employment measures in the two surveys.)

We would expect that with an expanding economy, federal tax revenues would rise and federal expenditures on unemployment insurance and other transfer programs would decline, reducing the federal budget deficit. (We discuss the effects of the business cycle on the federal budget deficit in Macroeconomics, Chapter 16, Section 16.6, Economics, Chapter 26, Section 26.6, and Essentials of Economics, Chapter 18, Section 18.6.) In fact, though, as the figure from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) at the top of this post shows, the federal budget deficit actually increased substantially during 2023 in comparison with 2022. The federal budget deficit from the beginning of government’s fiscal year on October 1, 2022 through July 2023 was $1,617 billion, more than double the $726 billion deficit during the same period in fiscal 2022.

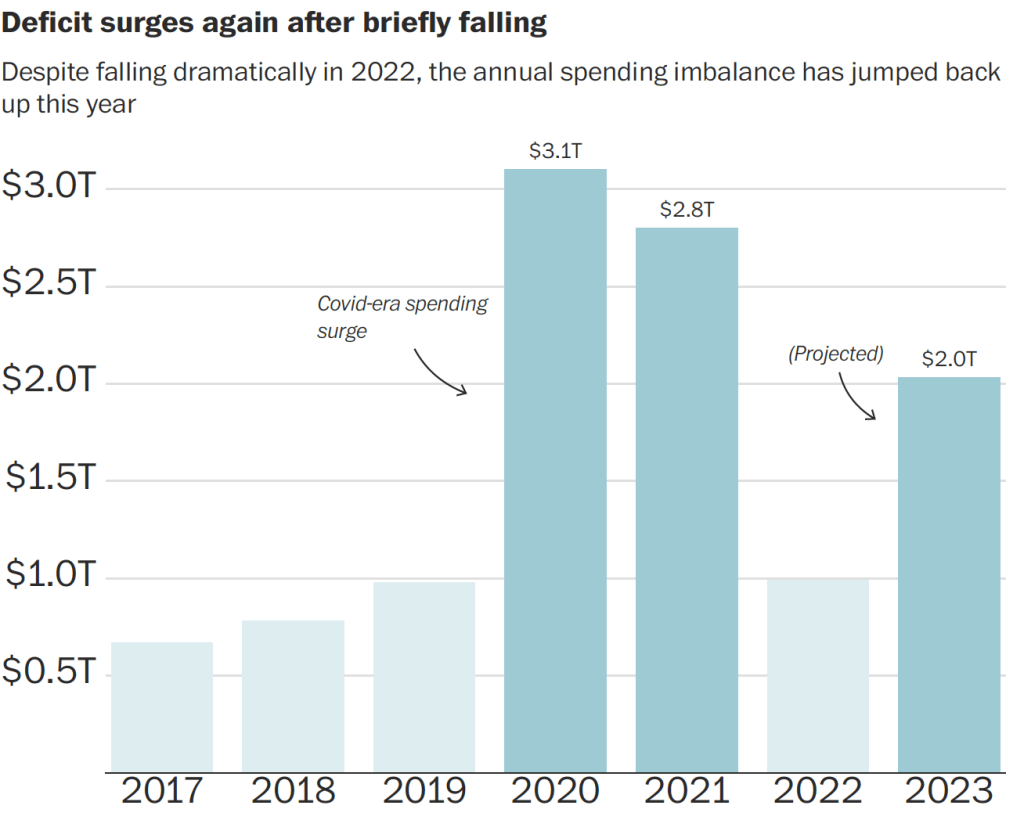

The following figure from an article in the Washington Post uses data from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget to illustrate changes in the federal budget deficit in recent years. The figure shows the sharp decline in the federal budget deficit in 2022 as the economic recovery from the Covid–19 pandemic increased federal tax receipts and reduced federal expenditures as emergency spending programs ended. Given the continuing economic recovery, the surge in the deficit during 2023 was unexpected.

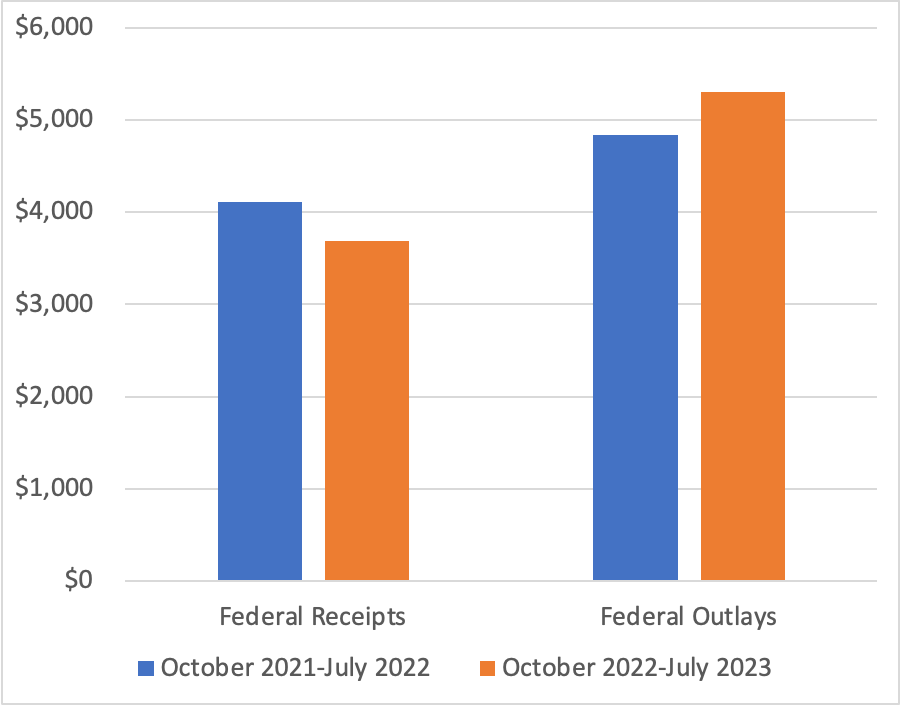

As the following figure shows, using CBO data, federal receipts—mainly taxes—are 10 percent lower this year than last year, and federal outlays—including transfer payments—are 11 percent higher. For receipts to fall and outlays to increase during an economic expansion is very unusual. As an article in the Wall Street Journal put it: “Something strange is happening with the federal budget this year.”

Note: The values on the vertical axis are in billions of dollars.

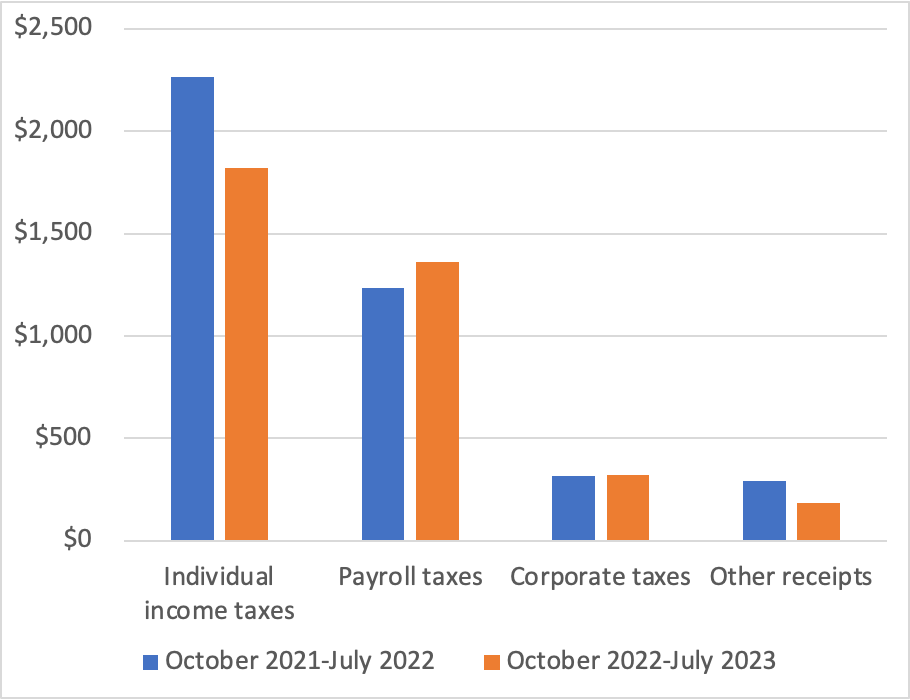

The following figure shows a breakdown of the decline in federal receipts. While corporate taxes and payroll taxes (primarily used to fund the Social Security and Medicare systems) increased, personal income tax receipts fell by 20 percent, and “other receipts” fell by 37 percent. The decline in other receipts is largely the result of a decline in payments from the Federal Reserve to the U.S. Treasury from $99 billion in 2022 to $1 billion in 2023. As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 17, Section 17.4 (Economics, Chapter 27, Section 27.4), Congress intended the Federal Reserve to be independent of the rest of the government. Unlike other federal agencies and departments, the Fed is self-financing rather than being financed by Congressional appropriations. Typically, the Fed makes a profit because the interest it earns on its holdings of Treasury securities is more than the interest it pays banks on their reserve deposits. After paying its operating costs, the Fed pays the rest of its profit to the Treasury. But as the Fed increased its target for the federal funds rate beginning in March 2022, it also increased the interest rate it pays banks on their reserve deposits. Because most of the securities it holds pay low interest rates, the Fed has begun running a deficit, reducing the payments it makes to the Treasury.

Note: The values on the vertical axis are in billions of dollars.

The reasons for the sharp decline in individual income taxes are less clear. The decline was in the “nonwithheld category” of individual income taxes; federal income taxes withheld from worker paychecks increased. People who are self-employed or who receive substantial income from sources such as capital gains from selling stocks, make quarterly estimated income tax payments. It’s these types of personal income taxes that have been unexpectedly low. Accordingly, smaller capital gains may be one explanation for the shortfall in federal revenues, but a more complete explanation won’t be possible until more data become available later in the year.

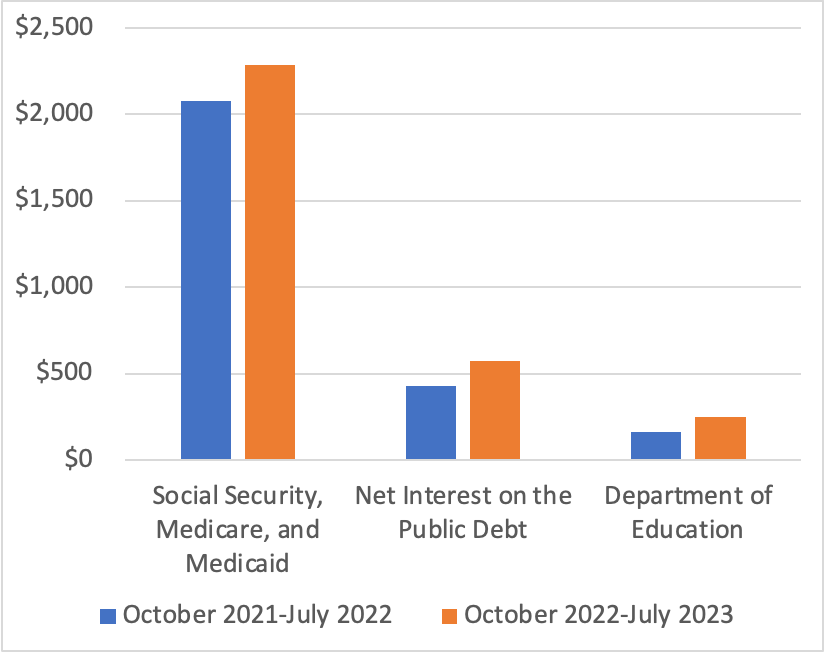

The following figure shows the categories of federal outlays that have increased the most from 2022 to 2023. The largest increase is in spending on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, with spending on Social Security alone increasing by $111 billion. This increase is due partly to an increase in the number of retired workers receiving benefits and partly to the sharp rise in inflation, because Social Security is indexed to changes in the consumer price index (CPI). Spending on Medicare increased by $66 billion or a surprisingly large 18 percent. Interest payments on the public debt (also called the federal government debt or the national debt) increased by $146 billion or 34 percent because interest rates on newly issued Treasury securities rose as nominal interest rates adjusted to the increase in inflation and because the public debt had increased significantly as a result of the large budget deficits of 2020 and 2021. The increase in spending by the Department of Education reflects the effects of the changes the Biden administration made to student loans eligible for the income-driven repayment plan. (We discuss the income-driven repayment plan for student loans in this blog post.)

Note: The values on the vertical axis are in billions of dollars.

The surge in federal government outlays occurred despite a $120 billion decline in refundable tax credits, largely due to the expiration of the expansion of the child tax credit Congress enacted during the pandemic, a $98 billion decline in Treasury payments to state and local governments to help offset the financial effects of the pandemic, and $59 billion decline in federal payments to hospitals and other medical facilities to offset increased costs due to the pandemic.

In this blog post from February, we discussed the challenges posed to Congress and the president by the CBO’s forecasts of rising federal budget deficits and corresponding increases in the federal government’s debt. The unexpected expansion in the size of the federal budget deficit for the current fiscal year significantly adds to the task of putting the federal government’s finances on a sound basis.

Data Indicate Continued Labor Market Easing

A job fair in Albuquerque, New Mexico earlier this year. (Photo from Zuma Press via the Wall Street Journal.)

In his speech at the Kansas City Fed’s Jackson Hole, Wyoming symposium, Fed Chair Jerome Powell noted that: “Getting inflation back down to 2 percent is expected to require a period of below-trend economic growth as well as some softening in labor market conditions.” To this point, there isn’t much indication that the U.S. economy is experiencing slower economic growth. The Atlanta Fed’s widely followed GDPNow forecast has real GDP increasing at a rapid 5.3 percent during the third quarter of 2023.

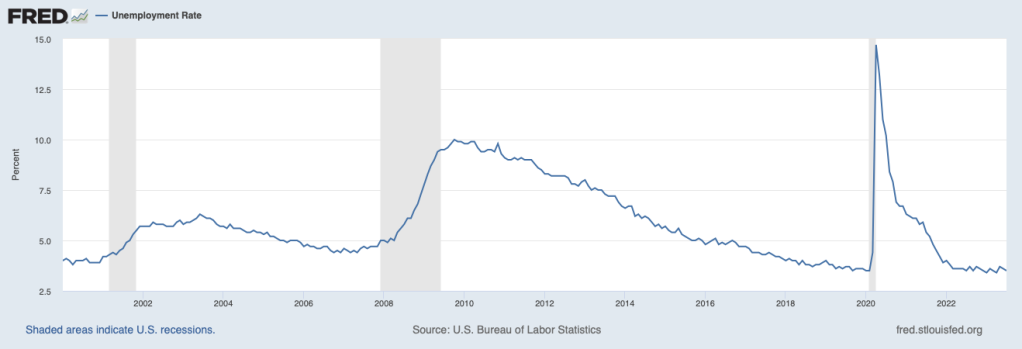

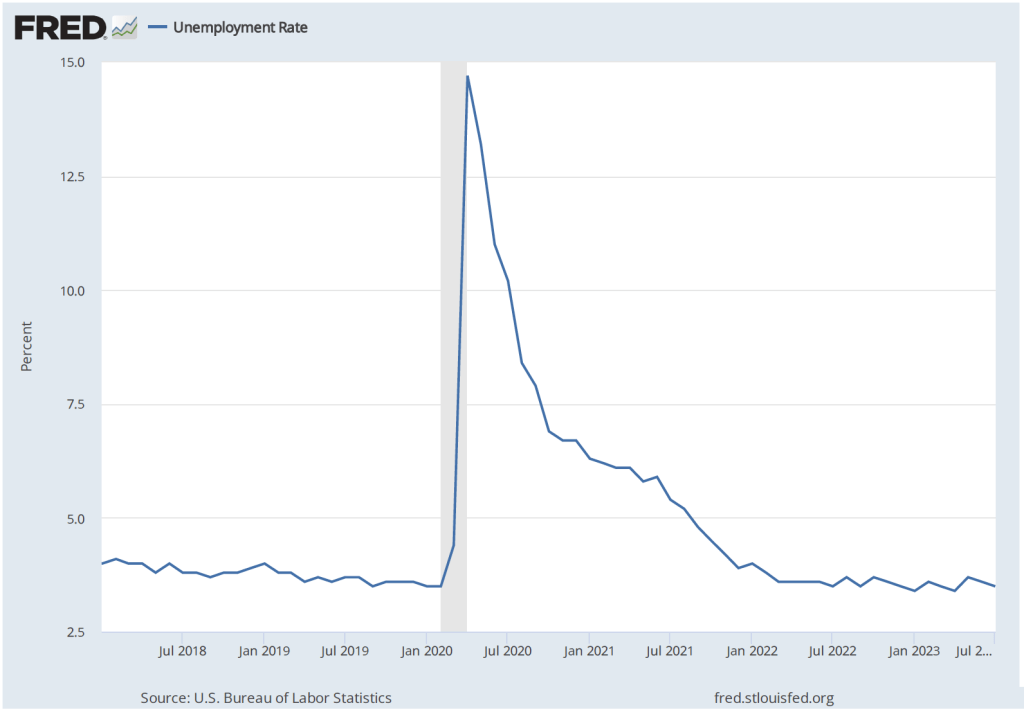

But the labor market does appear to be softening. The most familiar measure of the state of the labor market is the unemployment rate. As the following figure shows, the unemployment rate remains very low.

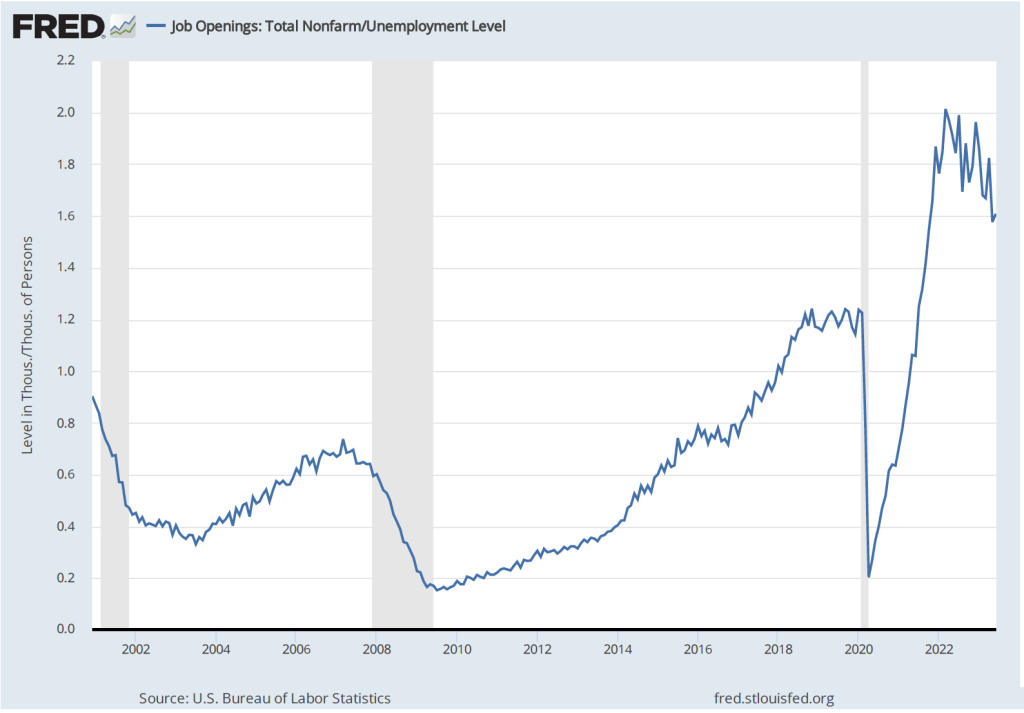

But, as we noted in this earlier post, an alternative way of gauging the strength of the labor market is to look at the ratio of the number of job openings to the number of unemployed workers. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) defines a job opening as a full-time or part-time job that a firm is advertising and that will start within 30 days. The higher the ratio of job openings to unemployed workers, the more difficulty firms have in filling jobs, and the tighter the labor market is. As indicated by the earlier quote from Powell, the Fed is concerned that in a very tight labor market, wages will increase more rapidly, which will likely lead firms to increase prices. The following figure shows that in July the ratio of job openings to unemployed workers has declined from the very high level of around 2.0 that was reached in several months between March 2022 and December 2022. The July 2023 value of 1.5, though, was still well above the level of 1.2 that prevailed from mid-2018 to February 2022, just before the beginning of the Covid–19 pandemic. These data indicate that labor market conditions continue to ease, although they remain tighter than they were just before the pandemic.

The following figure shows movements in the quit rate. The BLS calculates job quit rates by dividing the number of people quitting jobs by total employment. When the labor market is tight and competition among firms for workers is high, workers are more likely to quit to take another job that may be offering higher wages. The quit rate in July 2023 had fallen to 2.3 percent of total employment from a high of 3.0 percent, reached in both November 2021 and April 2022. The quit rate was back to its value just before the pandemic. The quit rate data are consistent with easing conditions in the labor market. (The data on job openings and quits are from the BLS report Job Openings and Labor Turnover—July 2023—the JOLTS report—released on August 29. The report can be found here.)

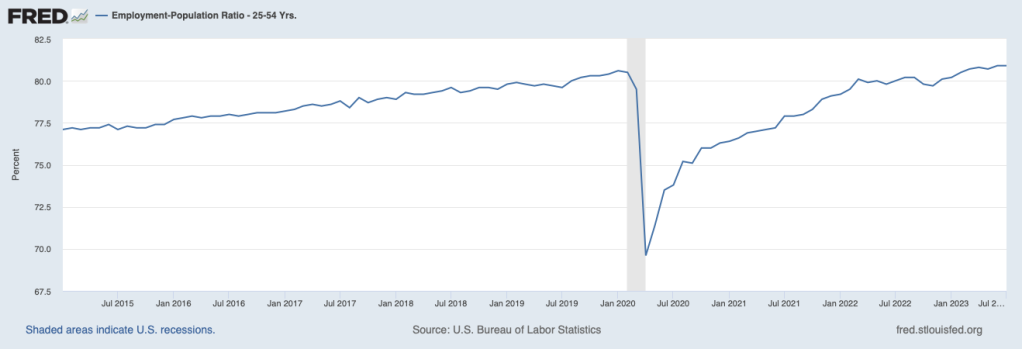

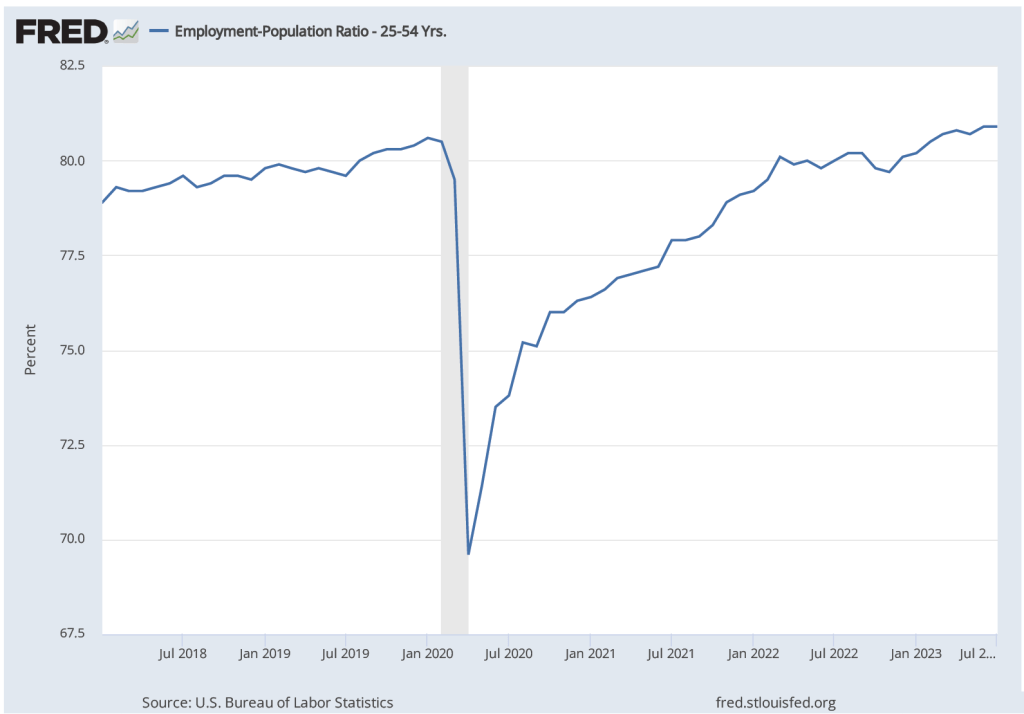

In his Jackson Hole speech, Powell noted that: “Labor supply has improved, driven by stronger participation among workers aged 25 to 54 and by an increase in immigration back toward pre-pandemic levels.” The following figure shows the employment-population ratio for people aged 25 to to 54—so-called prime-age workers. In July 2023, 80.9 percent of people in this age group were employed, actually above the ratio of 80.5 percent just before the pandemic. This increase in labor supply is another indication that the labor market disruptions caused by the pandemic has continued to ease, allowing for an increase in labor supply.

Taken together, these data indicate that labor market conditions are easing, likely reducing upward pressure on wages, and aiding the continuing decline in the inflation rate towards the Fed’s 2 percent target. Unless the data for August show an acceleration in inflation or a tightening of labor market conditions—which is certainly possible given what appears to be a strong expansion of real GDP during the third quarter—at its September meeting the Federal Open Market Committee is likely to keep its target for the federal funds rate unchanged.

Is the U.S. Economy Coming in for a Soft Landing?

The Federal Reserve building in Washington, DC. (Photo from Bloomberg News via the Wall Street Journal.)

The key macroeconomic question of the past two years is whether the Federal Reserve could bring down the high inflation rate without triggering a recession. In this blog post from back in February, we described the three likely macroeconomic outcomes as:

- A soft landing—inflation returns to the Fed’s 2 percent target without a recession occurring.

- A hard landing—inflation returns to the Fed’s 2 percent target with a recession occurring.

- No landing—inflation remains above the Fed’s 2 percent target but no recession occurs.

The following figure shows inflation measured as the percentage change in the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index and in the core PCE, which excludes food and energy prices. Recall that the Fed uses inflation as measured by the PCE to determine whether it is hitting its inflation target of 2 percent. Because food and energy prices tend to be volatile, many economists inside and outside of the Fed use the core PCE to better judge the underlying rate of inflation—in other words, the inflation rate likely to persist in at least the near future.

The figure shows that inflation first began to rise above the Fed’s target in March 2021. Most members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) believed that the inflation was caused by temporary disruptions to supply chains caused by the effects of the Covid–19 pandemic. Accordingly, the FOMC didn’t raise its target for the federal funds from 0 to 0.25 percent until March 2022. Since March 2022, the FOMC has raised its target for the federal funds rate in a series of steps until the target range reached 5.25 to 5.50 percent following the FOMC’s July 26, 2023 meeting.

PCE inflation peaked at 7.0 percent in June 2022 and had fallen to 2.9 percent in June 2023. Core PCE had a lower and earlier peak of 5.4 percent in February 2023, but had experienced a smaller decline—to 4.1 percent in June 2023. Inflation as measured by the consumer price index (CPI) followed a similar pattern, as shown in the following figure. Inflation measured by core CPI reached a lower peak than did inflation measured by the CPI and declined by less through June 2023.

As inflation has been falling since mid-2022, , the unemployment rate has remained low and the employment-population ratio for prime-age workers (workers aged 25 to 54) has risen above its 2019 pre-pandemic peak, as the following two figures show.

So, the Fed seems to be well on its way to achieving a soft landing. But in the press conference following the July 26 FOMC meeting Chair Jerome Powell was cautious in summarizing the inflation situation:

“Inflation has moderated somewhat since the middle of last year. Nonetheless, the process of getting inflation back down to 2 percent has a long way to go. Despite elevated inflation, longer-term inflation expectations appear to remain well anchored, as reflected in a broad range of surveys of households, businesses, and forecasters, as well as measures from financial markets.”

By “longer-term expectations appear to remain well anchored,” Powell was referring to the fact that households, firms, and investors appear to be expecting that the inflation rate will decline over the following year to the Fed’s 2 percent target.

Those economists who still believe that there is a good chance of a recession occuring during the next year have tended to focus on the following three points:

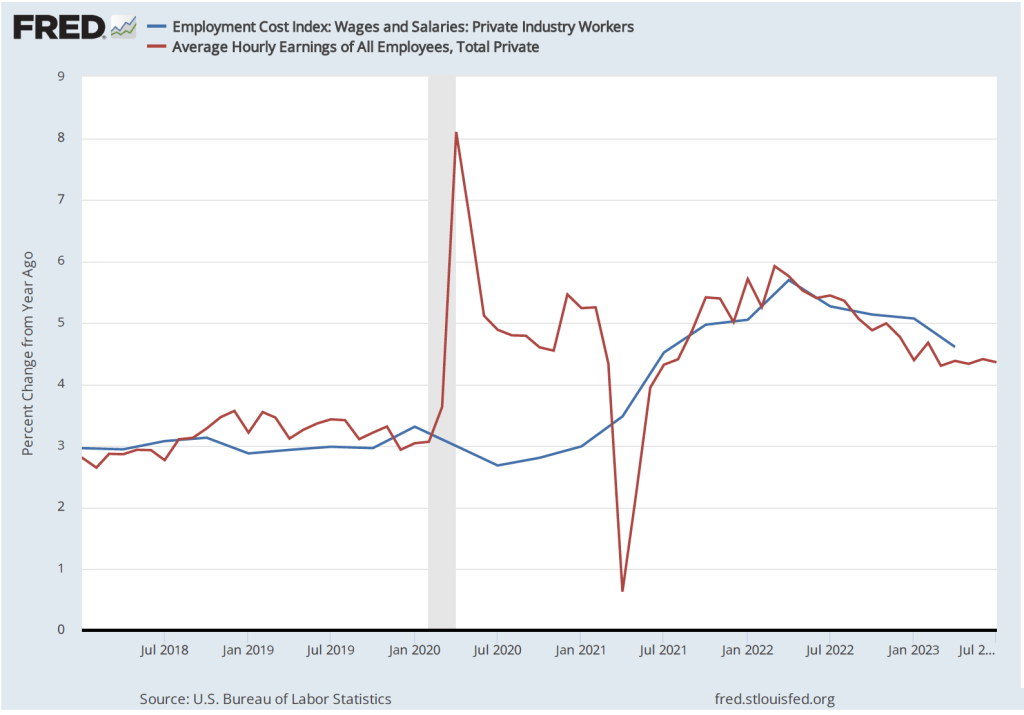

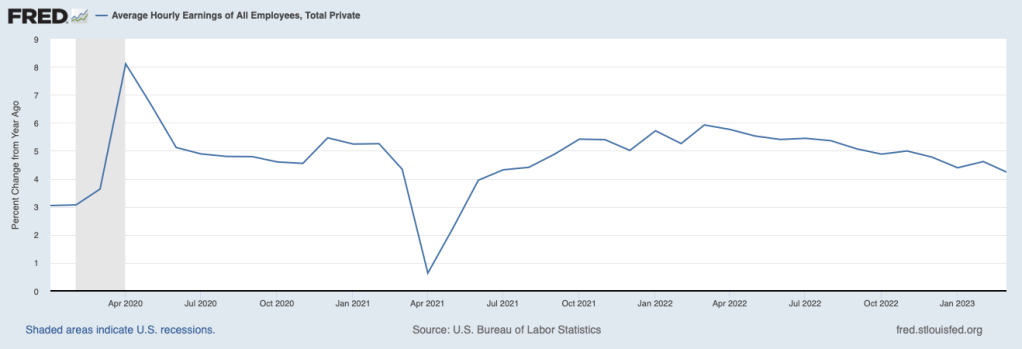

1. As shown in the following two figures, the labor market remains tight, with wage increases remaining high—although slowing in recent months—and the ratio of job openings to the number of unemployed workers remaining at historic levels—although that ratio has also been declining in recent months. If the labor market remains very tight, wages may continue to rise at a rate that isn’t consistent with 2 percent inflation. In that case, the FOMC may have to persist in raising its target for the federal funds rate, increasing the chances for a recession.

2. The lagged effect of the Fed’s contractionary monetary policy over the past year—increases in the target for the federal funds rate and quantitative tightening (allowing the Fed’s holdings of Treasury securites and mortgage-backed securities to decline; a process of quantitative tightening (QT))—may have a significant negative effect on the growth of aggegate demand in the coming months. Economists disagree on the extent to which monetary policy has lagged effects on the economy. Some economists believe that lags in policy have been significantly reduced in recent years, while other economists believe the lags are still substantial. The lagged effects of monetary policy, if sufficiently large, may be enough to push the economy into a recession.

3. The economies of key trading partners, including the European Union, the United Kingdom, China, and Japan are either growing more slowly than in the previous year or are in recession. The result could be a decline in net exports, which have been contributing to the growth of aggregate demand since early 2021.

In summary, we can say that in early August 2023, the probability of the Fed bringing off a soft landing has increased compared with the situation in mid-2022 or even at the beginning of 2023. But problems can still arise before the plane is safely on the ground.

Glenn on Bank Regulation

(Photo from the Wall Street Journal.)

This opinion column first appeared on barrons.com. It is also on the web site of the American Enterprise Institute.

Runs at Silicon Valley Bank and others emerged quickly and drove steep losses in regional bank equity values. Regulators shouldn’t have been caught by surprise, but at least they should take lessons from the shock. The subsequent ad hoc fixes to deposit insurance and assurances that the banking system is sufficiently well-capitalized don’t yet suggest a serious policy focus on those lessons. Calls for much higher levels of bank capital and tighter financial regulation notwithstanding, deeper questions about bank regulation merit greater attention.

Runs are a feature of banking. Banks transform short-term, liquid (even demandable) deposits into longer-term, sometimes much less liquid assets. Bank capital offers a partial buffer against the risk of a run, though a large-scale dash for cash can topple almost any institution, as converting blocks of assets to cash quickly to satisfy deposit withdrawals is almost sure to bring losses. The likelihood of a run goes up with bad news or rumors about the bank and correlation among depositors’ on their demand for funds back. That’s what happened at Silicon Valley Bank. Think also George Bailey’s impassioned speech in the classic movie It’s a Wonderful Life, explaining how maturity and liquidity transformations can unravel, with costs to depositors, bankers, and credit reductions to local businesses and households. The bank examiner in the movie, eager to get home, didn’t see it coming.

While bank runs and banking crises can be hard to predict, a simple maxim can guide regulation and supervision: Increase scrutiny in areas and institutions in which significant changes are occurring over a short period. On an aggregate level, the sharp, rapid increase in the federal funds rate since March 2022 should have focused attention on asset values and interest rate risks. So, too, should the fast potential compression in values of office real estate in many locations as a consequence of pandemic-related working shifts and rate hikes. At the bank level, significant inflows of deposits—particularly uninsured deposits—merit closer risk review. This approach isn’t limited to banking. A recent report of the Brookings-Chicago Booth Task Force on Financial Stability, co-chaired by Donald Kohn and me, put forth a similar change-based approach to scrutiny of nonbank financial institutions.

Such an approach would have magnified supervisory attention to Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic Bank . It also suggests the desirability of greater scrutiny and stress testing of midsize banks generally facing interest rate and commercial real estate risk. Those stress tests can give the Fed and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. an indication of capital adequacy concerns that could give rise to mergers or bank closures.

Even with this enhanced regulatory and supervisory attention, two major questions remain: For bank liabilities, what role should deposit insurance play in forestalling costly runs? For bank assets, what role should banks play in commercial lending?

Actions taken since Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse have effectively increased deposit-insurance guarantees for troubled institutions. But the absence of a clearer policy framework for dealing with uninsured deposits dragged out the unwinding of First Republic Bank and threatens other institutions experiencing rapid deposit increases and interest rate risk. When regulators asserted in the wake of the runs that the status quo of a $250,000 limit remained unchanged, they lacked both credibility and a means to reduce uncertainty about future policy actions in a run. That makes runs at vulnerable institutions both more likely and more severe. One reform would be to increase deposit insurance limits for transaction accounts of households and small and midsize firms, as recently proposed by the FDIC. Of course, even this reform raises concerns about implementation, how to price the enhanced coverage, and whether supervision will shift toward the “focus on the changes” framework I outlined earlier.

Retaining a more modest role for deposit insurance raises a larger question: What role should banks play in business lending for working capital, investment, and commercial real estate? The FDIC is mandated to resolve bank failures at the least cost to the deposit-insurance fund, but following that path may lead to more mergers of vulnerable institutions into the nations’ largest banks. While consolidation may mitigate risks for depositors with greater diversification of deposits, it leaves open effects on the mix of lending. Knowing local borrowers better, small and midsize banks have a prominent local lending presence in commercial and industrial loans and real estate. Whether such projects would be financed in a similar mix by local branches of megabanks is a question. Congress should consider whether other alternatives might be reasonable. It might permit consolidation among smaller institutions, even if more costly in resolution in the near term to taxpayers. Or nonbank institutions could be permitted to play a role in resolving troubled banks. The latter mechanism should be considered, as nonbank asset managers like Blackstone or BlackRock could fund loans originated by local banks.

Two lessons for regulation loom large. The first is that attention should be paid to policy risk management as well as bank risk management in identifying areas of concern. Think easy money and the reach for yield, inflationary fiscal and monetary policy during the pandemic, and the Fed’s rapid-fire increase in short-term rates to combat stubborn inflation. Second, regulators and Congress need to be wary of both too much deposit insurance (with likely increased risk-taking and pressure on supervision) and too little deposit insurance (with likely jumps in banking concentration and disruption of local credit to businesses).

One can reasonably anticipate additional erosion of capital in non-money-center banks from rising interest rates and lower office real estate collateral values, hopefully motivating a quick grasp of these lessons. While banks don’t have to mark assets to market if current and can survive turbulence until monetary policy eases, potential runs can upset this equilibrium. Declining regional bank stock prices make this risk clear. Only good fortune or a more thoughtful policy stand in the way of additional bank distress and attendant credit supply reductions.

Unraveling the Mysteries of the May 2023 Employment Situation Report

(Photo from the Associated Press via the Wall Street Journal.)

During most periods, the “Employment Situation” report that the Bureau of Labor Statistics issues on the first Friday of each month includes the most closely watched macroeconomic data. Since the spring of 2021, high inflation rates have made the BLS’s “Consumer Price Index Summary” at least a close second in interest to the employment report. The data in the CPI report is usually more readily comprehensible than the data in the employment report. So, we think it’s worth class time to go into some of the details of the employment report, as we do in Macroeconomics, Chapter 9, Section 9.1, Economics, Chapter 19, Section 19.1, and Essentials of Economics, Chapter 13, Section 13.1.

When the BLS released the May employment report, the Wall Street Journal noted that: “Employers added 339,000 jobs last month; unemployment rate rose to 3.7%.” Employment increased … but the unemployment rate also rose? How is that possible? One key to understanding media accounts of the report is to note that the report contains data from two separate surveys: 1) the household survey and 2) the employment or establishment survey. As in the statement just quoted from the Wall Street Journal, media accounts often mix data from the two surveys.

The data showing an increase of 339,000 jobs in May are from the payroll survey, while the data showing that the unemployment rate rose are from the household survey. Below we reproduce part of the relevant table from the report showing some of the data from the household survey. Note that total employment in the household survey falls by 310,000, so there appears to be no contradiction to explain—the unemployment rate increased because the number of people employed fell and the number of people unemployed rose. But why, then, did employment rise in the payroll survey?

Employment can rise in one survey and fall in the other because: 1) the types of employment measured in the two series differ, 2) the periods during which the data are collected differ, and 3) because of measurement error. The household survey uses a broader measure of employment that includes several categories of workers who are not included in the payroll survey: agricultural workers, self-employed workers, unpaid workers in family businesses, workers employed in private households rather than in businsses, and workers on unpaid leave from their jobs. In addition, the payroll employment numbers are revised—sometimes substantially—as additional data are collected from firms, while the household employment numbers are subject to much smaller revisions because data in the household survey are collected during a single week. A detailed discussion of the differences between the employment measures in the two series can be found here.

Usefully, the BLS publishes a series labeled “Adjusted employment” that estimates what the value for household employment would be if the household survey was measuring the same categories of employment as the payroll survey. In this case, the adjusted employment series shows an increase in employment in May of 394,000—close to the payroll survey’s increase of 339,000.

To summarize, the May employment report indicates that payroll employment increased, while the non-payroll categories of household employment declined, and the unemployment rate rose. Note also in the table above that the number of people counted as not being in labor force rose slightly and the employment-population ratio fell slightly. Average weekly hours (not shown in the table above) decreased slightly from 34.4 hours per week to 34.3.

A reasonable conclusion from the report is that the labor market remains strong, although it may have weakened slightly. Prior to release of the report, there was much speculation in the business press about how the report might affect the deliberations of the Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committe (FOMC) at its next meeting to be held on June 13th and 14th. The report showed stronger employment growth than economists surveyed by Dow Jones had expected, indicating that the FOMC was likely to remain concerned that a tight labor market might continue to put upward pressure on wages, which firms could pass through to higher prices. Members of the FOMC had been signalling that they were likely to keep their target for the federal funds rate unchanged in June. The reported employment increase was likely not large enough to cause the FOMC to change course.

The Fed Continues to Walk a Tightrope

At its Wednesday, May 3, 2023 meeting, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) raised its target for the federal funds rate by 0.25 percentage point to a range of 5.00 to 5.25. The decision by the committee’s 11 voting members was unanimous. After each meeting, the FOMC releases a statement (the statement for this meeting can be found here) explaining its reasons for its actions at the meeting.

The statement for this meeting had a key change from the statement the committee issued after its last meeting on March 22. The previous statement (found here) included this sentence:

“The Committee anticipates that some additional policy firming may be appropriate in order to attain a stance of monetary policy that is sufficiently restrictive to return inflation to 2 percent over time.”

In the statement for this meeting, the committee rewrote that sentence to read:

“In determining the extent to which additional policy firming may be appropriate to return inflation to 2 percent over time, the Committee will take into account the cumulative tightening of monetary policy, the lags with which monetary policy affects economic activity and inflation, and economic and financial developments.”

This change indicates that the FOMC has stopped—or at least suspended—use of forward guidance. As we explain in Money, Banking, and the Financial System, Chapter 15, Section 5.2, forward guidance refers to statements by the FOMC about how it will conduct monetary policy in the future.

After the March meeting, the committee was providing investors, firms, and households with the forward guidance that it intended to continue raising its target for the federal funds rate—which is what the reference to “additional policy firming” means. The statement after the May meeting indicated that the committee was no longer giving guidance about future changes in its target for the federal funds rate other than to state that it would depend on the future state of the economy. In other words, the committee was indicating that it might not raise its target for the federal funds rate after its next meeting on June 14. The committee didn’t indicate directly that it was pausing further increases in the federal funds rate but indicated that pausing further increases was a possible outcome.

Following the end of the meeting, Fed Chair Jerome Powell conducted a press conference. Although not yet available when this post was written, a transcript will be posted to the Fed’s website here. Powell made the following points in response to questions:

- He was not willing to move beyond the formal statement to indicate that the committee would pause further rate increases.

- He believed that the bank runs that had led to the closure and sale of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and First Republic Bank were likely to be over. He didn’t believe that other regional banks were likely to experience runs. He indicated that the Fed needed to adjust its regulatory and supervisory actions to help ensure that similar runs didn’t happen in the future.

- He repeated that he believed that the Fed could achieve its target inflation rate of 2 percent without the U.S. economy experiencing a recession. In other words, he believed that a soft landing was still possible. He acknowledged that some other members of the committee and the committee’s staff economist disagreed with him and expected a mild recession to occur later this year.

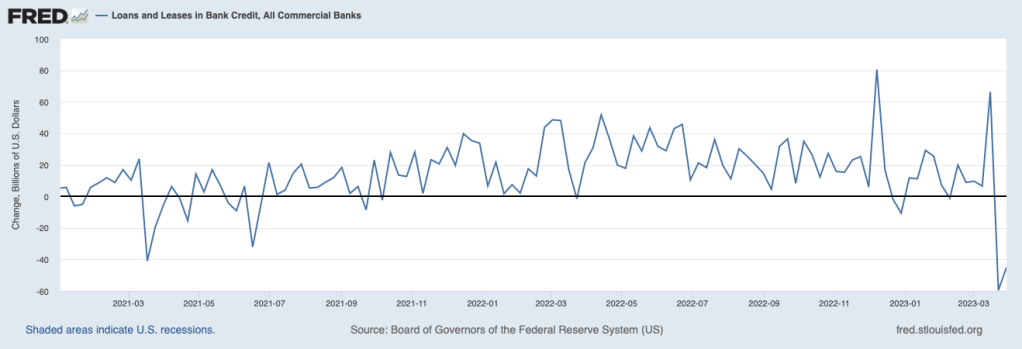

- He stated that as banks have attempted to become more liquid following the failure of the three regional banks, they have reduced the volume of loans they are making. This credit contraction has an effect on the economy similar to that of an increase in the federal funds rate in that increases in the target for the federal funds rate are also intended to reduce demand for goods, such as housing and business fixed investment, that depend on borrowing. He noted that both those sectors had been contracting in recent months, slowing the economy and potentially reducing the inflation rate.

- He indicated that although inflation had declined somewhat during the past year, it was still well above the Fed’s target. He mentioned that wage increases were still higher than is consistent with an inflation rate of 2 percent. In response to a question, he indicated that if the inflation rate were to fall from current rates above 4 percent to 3 percent, the FOMC would not be satisfied to accept that rate. In other words, the FOMC still had a firm target rate of 2 percent.

In summary, the FOMC finds itself in the same situation it has been in since it began raising its target for the federal funds rate in March 2022: Trying to bring high inflation rates back down to its 2 percent target without causing the U.S. economy to experience a significant recession.

4/29/23 Podcast – Authors Glenn Hubbard & Tony O’Brien discuss a hard vs. soft landing, the debt ceiling, and an economics view of the CHIPS act passed in 2022.

Join authors Glenn Hubbard & Tony O’Brien as they discuss the state of the landing the economy will achieve – hard vs. soft – or “no landing”. Also, they address the debt ceiling and the barriers it might present to a recovery. We also delve into the Chips Act and what economics has to say about the subsidy of a particular industry. Gain insights into today’s economy through our final podcast of the 2022-2023 academic year! Our discussion covers these points but you can also check for updates on our blog post that can be found HERE .

Is a Soft Landing More Likely Now?

Photo from the Wall Street Journal.

The Federal Reserve’s goal has been to end the current period of high inflation by bringing the economy in for a soft landing—reducing the inflation rate to closer to the Fed’s 2 percent target while avoiding a recession. Although Fed Chair Jerome Powell has said repeatedly during the last year that he expected the Fed would achieve a soft landing, many economists have been much more doubtful.

It’s possible to read recent economic data as indicating that it’s more likely that the economy is approaching a soft landing, but there is clearly still a great deal of uncertainty. On April 12, the Bureau of Labor Statistics released the latest CPI data. The figure below shows the inflation rate as measured by the CPI (blue line) and by core CPI—which excludes the prices of food and fuel (red line). In both cases the inflation rate is the percentage change from the same month in the previous year.

The inflation rate as measured by the CPI has been trending down since it hit a peak of 8.9 percent in June 2022. The inflation rate as measured by core CPI has been trending down more gradually since it reached a peak of 6.6 percent in September 2022. In March, it was up slightly to 5.6 percent from 5.5 percent in February.

As the following figure shows, payroll employment while still increasing, has been increasing more slowly during the past three months—bearing in mind that the payroll employment data are often subject to substantial revisions. The slowing growth in payroll employment is what we would expect with a slowing economy. The goal of the Fed in slowing the economy is, of course, to bring down the inflation rate. That payroll employment is still growing indicates that the economy is likely not yet in a recession.

The slowing in employment growth has been matched by slowing wage growth, as measured by the percentage change in average hourly earnings. As the following figure shows, the rate of increase in average hourly earnings has declined from 5.9 percent in March 2022 to 4.2 percent in March 2023. This decline indicates that businesses are experiencing somewhat lower increases in their labor costs, which may pass through to lower increases in prices.

Credit conditions also indicate a slowing economy As the following figure shows, bank lending to businesses and consumers has declined sharply, partly because banks have experienced an outflow of deposits following the failure of Silicon Valley and Signature Banks and partly because some banks have raised their requirements for households and firms to qualify for loans in anticipation of the economy slowing. In a slowing economy, households and firms are more likely to default on loans. To the extent that consumers and businesses also anticipate the possibility of a recession, they may have reduced their demand for loans.

But such a sharp decline in bank lending may also be an indication that the economy is not just slowing, on its way to a making a soft landing, but is on the verge of a recession. The minutes of the March meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) included the information that the FOMC’s staff economists forceast “at the time of the March meeting included a mild recession starting later this year, with a recovery over the subsequent two years.” (The minutes can be found here.) The increased chance of a recession was attributed largely to “banking and financial conditions.”

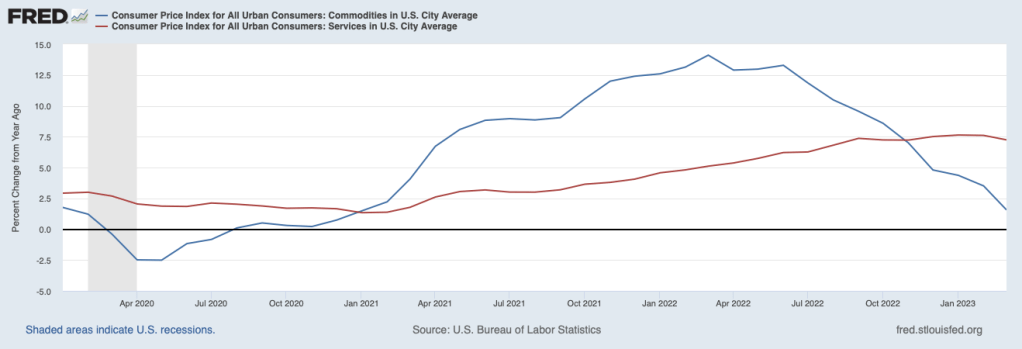

At its next meeting in May, the FOMC will have to decide whether to once more increase its target range for the federal funds rate. The target range is currently 4.75 percent to 5.00 percent. The FOMC will have to decide whether inflation is on a course to fall back to the Fed’s 2 percent target or whether the FOMC needs to further slow the economy by increasing its target range for the federal funds rate. One factor likely to be considered by the FOMC is, as the following figure shows, the sharp difference between the inflation rate in prices of goods (blue line) and the inflation rate in prices of services (red line).

During the period from January 2021 to November 2022, inflation in goods was higher—often much higher—than inflation in services. The high rates of inflation in goods were partly the result of disruptions to supply chains resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic and partly due to a surge in demand for goods as a result of very expansionary fiscal and monetary policies. Since November 2022, inflation in the prices of services has remained high, while inflation in the prices of goods has continued to decline. In March, goods inflation was only 1.6 percent, while services inflation was 7.2 percent. In his press conference following the last FOMC meeting, Fed Chair Jerome Powell stated that as long as services inflation remains high “it would be very premature to declare victory [over inflation] or to think that we’ve really got this.” (The transcript of Powell’s news conference can be found here.) This statement coupled with the latest data on service inflation would seem to indicate that Powell will be in favor of another 0.25 percentage point increase in the federal funds rate target range.

The Fed’s inflation target is stated in terms of the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) price index, not the CPI. The Bureau of Economic Analysis will release the March PCE on April 28, before the next FOMC meeting. If the Fed is as closely divided as it appears to be over whether additional increases in the federal funds rate target range are necessary, the latest PCE data may prove to have a significan effect on their decision.

So—as usual!—the macroeconomic picture is murky. The economy appears to be slowing and inflation seems to be declining but it’s still difficult to determine whether the Fed will be able to bring inflation back to its 2 percent target without causing a recession.