The Problem with Bitcoin as Money

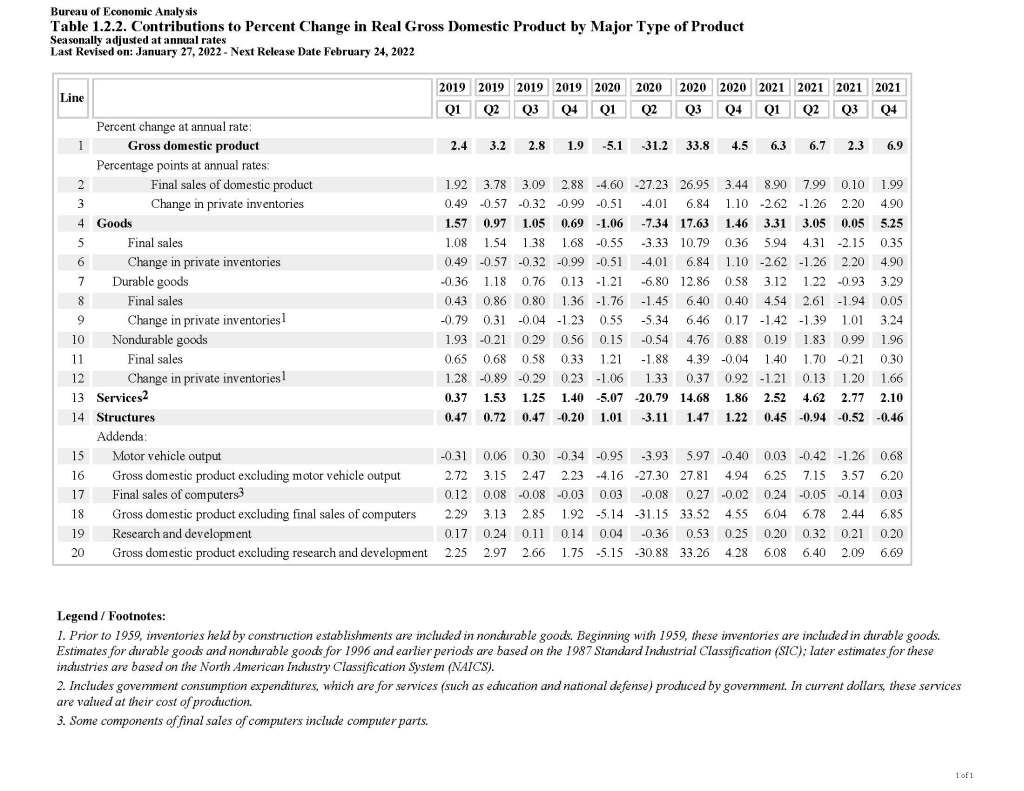

Bitcoin has failed in their original purpose of providing a digital currency that could be used in everyday transactions like buying lunch and paying a cellphone bill. As the following figure shows, swings in the value of bitcoin have been too large to make useful as a medium of exchange like dollar bills. During the period shown in the figure—from July 2021 to February 2022—the price of bitcoin has increased by more than $30,000 per bitcoin and then fallen by about the same amount. Bitcoin has become a speculative asset like gold. (We discuss bitcoin in the Apply the Concept, “Are Bitcoins Money?” which appears in Macroeconomics, Chapter 14, Section 14.2 and in Economics, Chapter 24, Section 24.2. In an earlier blog post found here we discussed how bitcoin has become similar to gold.)

The vertical axis measures the price of bitcoin in dollars per bitcoin.

The Slow U.S. Payments Increases the Appeal of a Digital Currency

Some economists and policymakers argue that there is a need for a digital currency that would do what bitcoin was originally intended to do—serve as a medium of exchange. Digital currencies hold the promise of providing a real-time payments system, which allow payments, such as bank checks, to be made available instantly. The banking systems of other countries, including Japan, China, Mexico, and many European countries, have real-time payment systems in which checks and other payments are cleared and funds made available in a few minutes or less. In contrast, in the United States, it can two days or longer after you deposit a check for the funds to be made available in your account.

The failure of the United States to adopt a real-time payments system has been costly to many lower-income people who are likely to need paychecks and other payments to be quickly available. In practice, many lower-income people: 1) incur bank overdraft fees, when they write checks in excess of the funds available in their accounts, 2) borrow money at high interest rates from payday lenders, or 3) pay a fee to a check cashing store when they need money more quickly than a bank will clear a check. Aaron Klein of the Brookings Institution estimates that lower-income people in the United States spend $34 billion annually as a result of relying on these sources of funds. (We discuss the U.S. payments system in Money, Banking, and the Financial System, 4th edition, Chapter 2, Section 2.3.)

The Problem with Stablecoins as Money

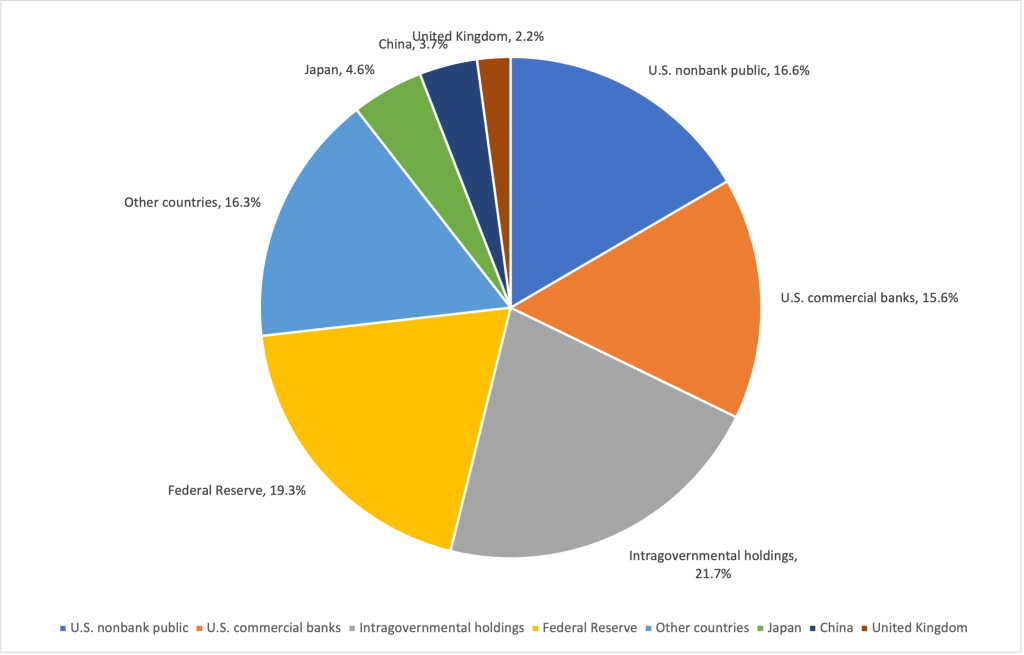

Some entrepreneurs have tried to return to the original idea of using cryptocurrencies as a medium of exchange by introducing stablecoins that can be bought and sold for a constant number of dollars—typically one dollar for one stablecoin. The issuers of stablecoins hold in reserve dollars, or very liquid assets like U.S. Treasury bills, to make credible the claim that holders of stablecoins will be able to exchange them one-for-one for dollars. Tether and Circle Internet Financial are the leading issuers of stablecoins.

So far, stablecoins have been used primarily to buy bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies rather than for day-to-day buying and selling of goods and services in stores or online. Financial regulators, including the U.S. Treasury and the Federal Reserve, are concerned that stablecoins could be a risk to the financial system. These regulators worry that issuers of stablecoins may not, in fact, keep sufficient assets in reserve to redeem them. As a result, stablecoins might be susceptible to runs similar to those that plagued the commercial banking system prior to the establishment of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation in the 1930s or that were experienced by some financial firms during the 2008 financial crisis. In a run, issuers of stablecoins might have to sell financial assets, such as Treasury bills, to be able to redeem the stablecoins they have issued. The result could be a sharp decline in the prices of these assets, which would reduce the financial strength of other firms holding the assets.

In 2019, Facebook (whose corporate name is now Meta Platforms) along with several other firms, including PayPal and credit card firm Visa, began preparations to launch a stablecoin named Libra—the name was later changed to Diem. In May 2021, the firms backing Diem announced that Silvergate Bank, a commercial bank in California, would issue the Diem stablecoin. But according to an article in the Wall Street Journal, the Federal Reserve had “concerns about [the stablecoin’s] effect on financial stability and data privacy and worried [it] could be misused by money launderers and terrorist financiers.” In early 2022, Diem sold its intellectual property to Silvergate, which hoped to still issue the stablecoin at some point.

A Federal Reserve Digital Currency?

If private firms or individual commercial banks have not yet been able to issue a digital currency that can be used in regular buying and selling in stores and online, should central banks do so? In January 2022, the Federal Reserve issued a report discussing the issues involved with a central bank digital currency (CBCD). As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 14, Section 14.2, most of the money supply of the United States consists of bank deposits. As the Fed’s report points out, because bank deposits are computer entries on banks’ balance sheets, most of the money in the United States today is already digital. As we discuss in Section 14.3, bank deposits are liabilities of commercial banks. In contrast, a CBCD would be a liability of the Fed or other central bank.

The Fed report lists the benefits of a CBCD:

“[I]t could provide households and businesses [with] a convenient, electronic form of central bank money, with the safety and liquidity that would entail; give entrepreneurs a platform on which to create new financial products and services; support faster and cheaper payments (including cross-border payments); and expand consumer access to the financial system.”

Importantly, the Fed indicates that it won’t begin issuing a CBCD without the backing of the president and Congress: “The Federal Reserve does not intend to proceed with issuance of a CBDC without clear support from the executive branch and from Congress, ideally in the form of a specific authorizing law.”

The Fed report acknowledges that “a significant number of Americans currently lack access to digital banking and payment services. Additionally, some payments—especially cross-border payments—remain slow and costly.” By issuing a CBDC, the Fed could help to reduce these problems by making digital banking services available to nearly everyone, including lower-income people who currently lack bank checking accounts, and by allowing consumers to have payments instantly available rather than having to wait for a check to clear.

The report notes that: “A CBDC would be the safest digital asset available to the general public, with no associated credit or liquidity risk.” Credit risk is the risk that the value of the currency might decline. Because the Fed would be willing to redeem a dollar of CBDC currency for a dollar or paper money, a CBDC has no credit risk. Liquidity risk is the risk that, particularly during a financial crisis, someone holding CBDC might not be able to use it to buy goods and services or financial assets. Fed backing of the CBDC makes it unlikely that someone holding CBDC would have difficulty using it to buy goods and services or financial assets.

But the report also notes several risks that may result from the Fed issuing a CBDC:

- Banks rely on deposits for the funds they use to make loans to households and firms. If large numbers of households and firms switch from using checking accounts to using CBDC, banks will lose deposits and may have difficulty funding loans.

- If the Fed pays interest on the CBDC it issues, households, firms, and investors may switch funds from Treasury bills, money market mutual funds, and other short-term assets to the CBDC, which might potentially disrupt the financial system. Money market mutual funds buy significant amounts of corporate commercial paper. Some corporations rely heavily on the funds they raise from selling commercial paper to fund their short-term credit needs, including paying suppliers and financial inventories.

- In a financial panic, many people may withdraw funds from commercial bank deposits and convert the funds into CBDC. These actions might destabilize the banking system.

- A related point: A CBDC might result in large swings in bank reserves, particularly during and after a financial panic. As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 14, Section 14.4 (Economics, Chapter 24, Section 24.4), increasing and decreasing bank reserves is one way in which the Fed carries out monetary policy. So fluctuations in bank reserves may make it more difficult for the Fed to conduct monetary policy, particularly during a financial panic. (This consideration is less important during times like the present when banks hold very large reserves.)

- Because the Fed has no experience in operating a retail banking operation, it would be likely that if it began issuing a CBDC, it would do so through commercial banks or other financial firms rather than doing so directly. These financial firms would then hold customers CBDC accounts and carry out the actual flow of payments in CBDC among households and firms.

The report notes that the Fed is only beginning to consider the many issues that would be involved in issuing a CBDC and still needs to gather feedback from the general public, financial firms, nonfinancial firms, and investors, as well as from policymakers in Washington.

Sources: Peter Rudegeair and Liz Hoffman, “Facebook’s Cryptocurrency Venture to Wind Down, Sell Assets,” Wall Street Journal, January 26, 2022; Liana Baker, Jesse Hamilton, and Olga Kharif, “Mark Zuckerberg’s Stablecoin Ambitions Unravel with Diem Sale Talks,” bloomberg.com, January 25, 2022; Amara Omeokwe, “U.S. Regulators Raise Concern With Stablecoin Digital Currency,” Wall Street Journal, December 17, 2022; Jeanna Smialek, “Fed Opens Debate over a U.S. Central Bank Digital Currency with Long-Awaited Report,”, January 20, 2022; Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Money and Payments: The U.S. Dollar in the Age of Digital Transformation, January 2022; and Aaron Klein, “The Fastest Way to Address Income Inequality? Implement a Real Time Payments System,” brookings.edu, January 2, 2019.