A job fair in Albuquerque, New Mexico earlier this year. (Photo from Zuma Press via the Wall Street Journal.)

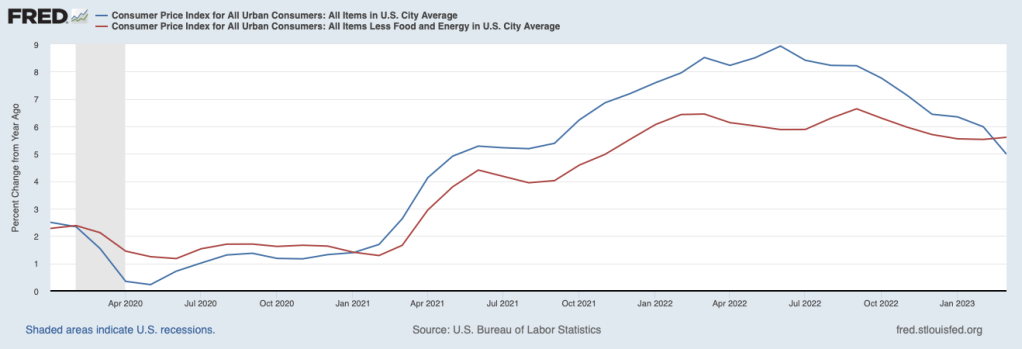

In his speech at the Kansas City Fed’s Jackson Hole, Wyoming symposium, Fed Chair Jerome Powell noted that: “Getting inflation back down to 2 percent is expected to require a period of below-trend economic growth as well as some softening in labor market conditions.” To this point, there isn’t much indication that the U.S. economy is experiencing slower economic growth. The Atlanta Fed’s widely followed GDPNow forecast has real GDP increasing at a rapid 5.3 percent during the third quarter of 2023.

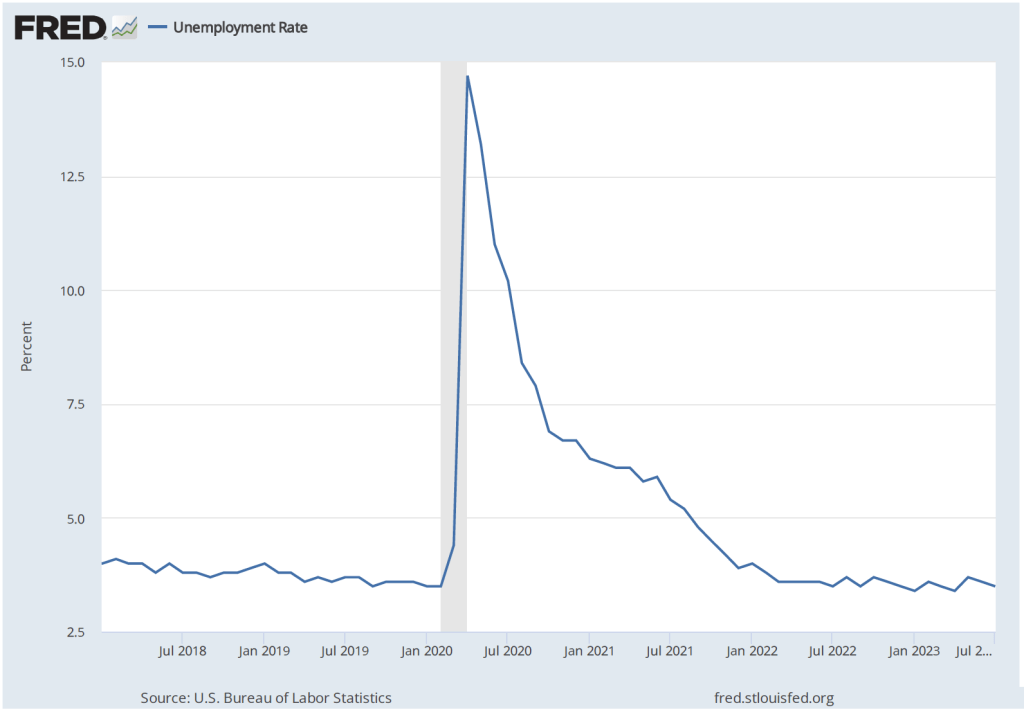

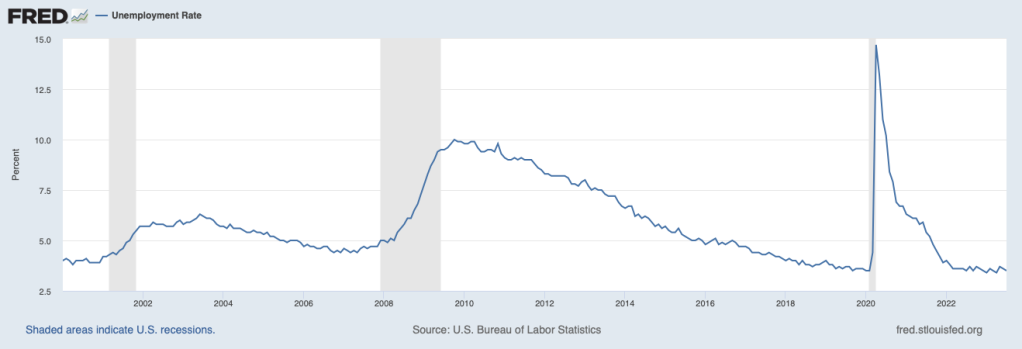

But the labor market does appear to be softening. The most familiar measure of the state of the labor market is the unemployment rate. As the following figure shows, the unemployment rate remains very low.

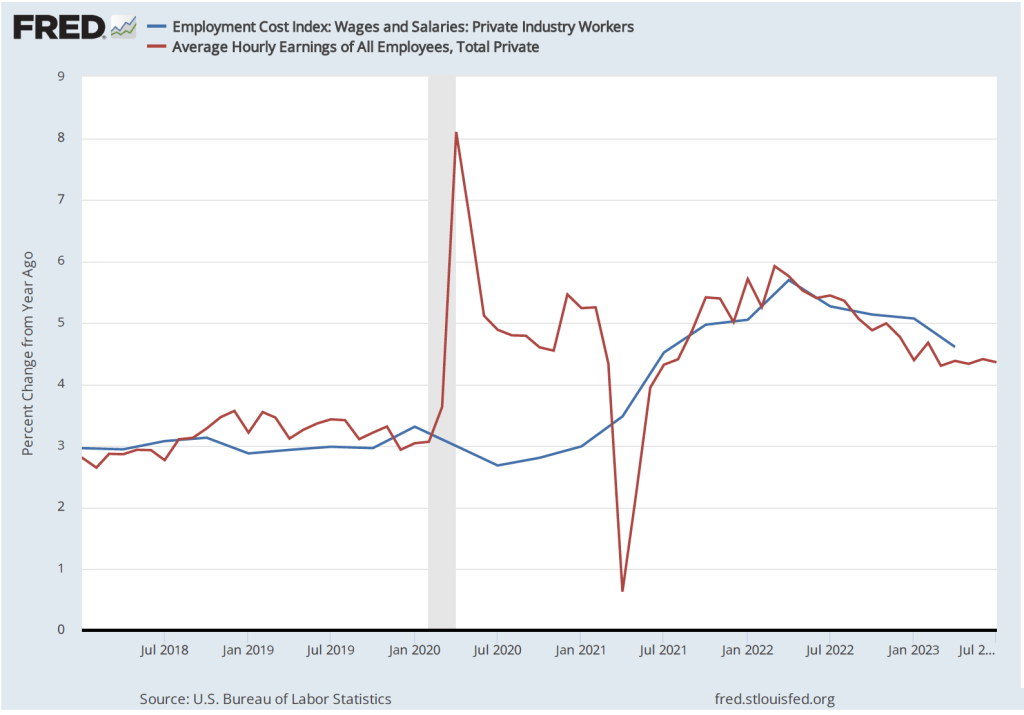

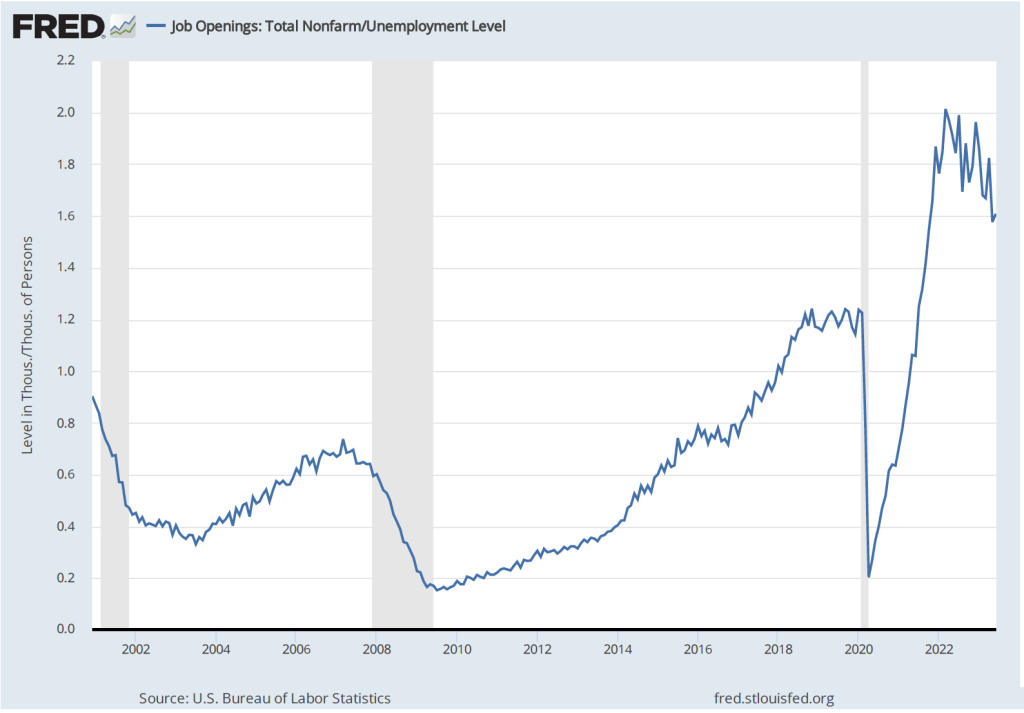

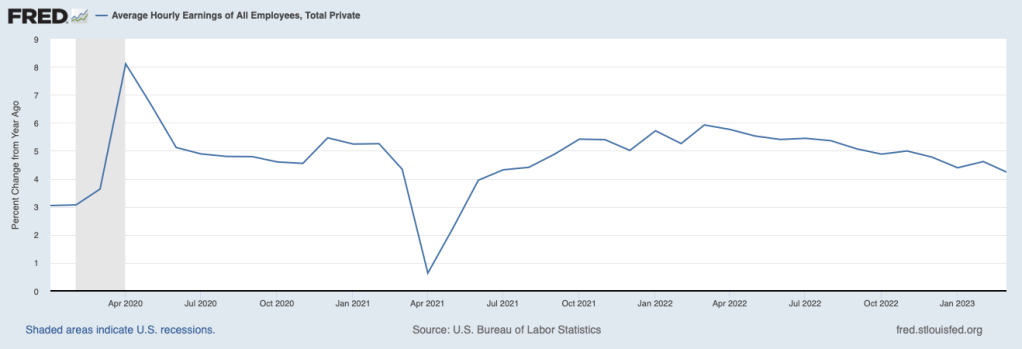

But, as we noted in this earlier post, an alternative way of gauging the strength of the labor market is to look at the ratio of the number of job openings to the number of unemployed workers. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) defines a job opening as a full-time or part-time job that a firm is advertising and that will start within 30 days. The higher the ratio of job openings to unemployed workers, the more difficulty firms have in filling jobs, and the tighter the labor market is. As indicated by the earlier quote from Powell, the Fed is concerned that in a very tight labor market, wages will increase more rapidly, which will likely lead firms to increase prices. The following figure shows that in July the ratio of job openings to unemployed workers has declined from the very high level of around 2.0 that was reached in several months between March 2022 and December 2022. The July 2023 value of 1.5, though, was still well above the level of 1.2 that prevailed from mid-2018 to February 2022, just before the beginning of the Covid–19 pandemic. These data indicate that labor market conditions continue to ease, although they remain tighter than they were just before the pandemic.

The following figure shows movements in the quit rate. The BLS calculates job quit rates by dividing the number of people quitting jobs by total employment. When the labor market is tight and competition among firms for workers is high, workers are more likely to quit to take another job that may be offering higher wages. The quit rate in July 2023 had fallen to 2.3 percent of total employment from a high of 3.0 percent, reached in both November 2021 and April 2022. The quit rate was back to its value just before the pandemic. The quit rate data are consistent with easing conditions in the labor market. (The data on job openings and quits are from the BLS report Job Openings and Labor Turnover—July 2023—the JOLTS report—released on August 29. The report can be found here.)

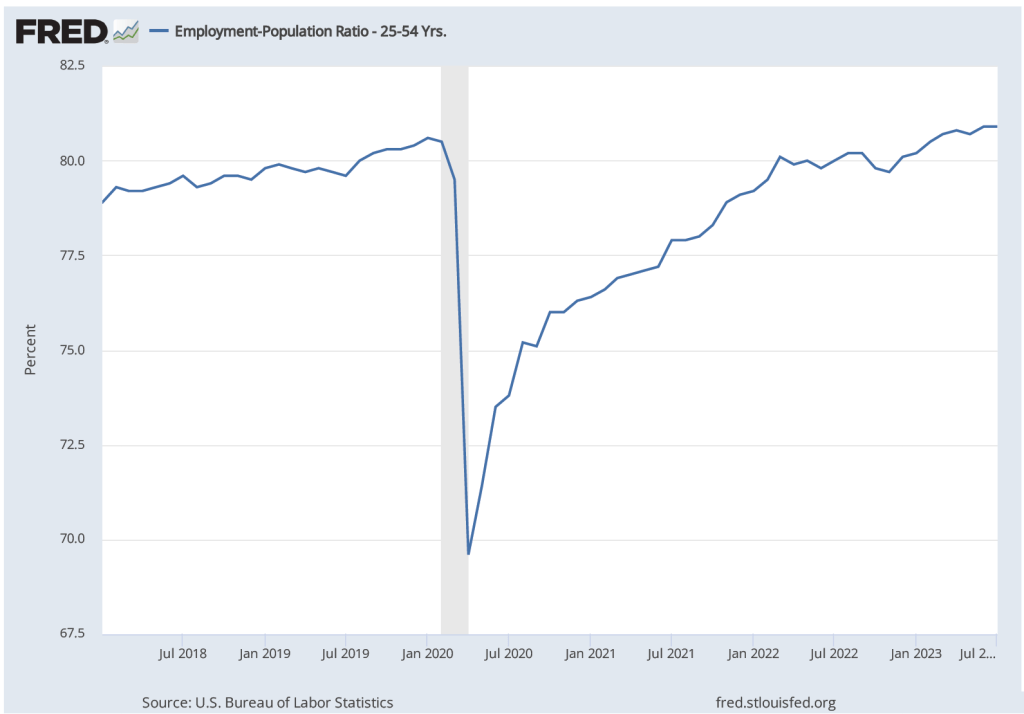

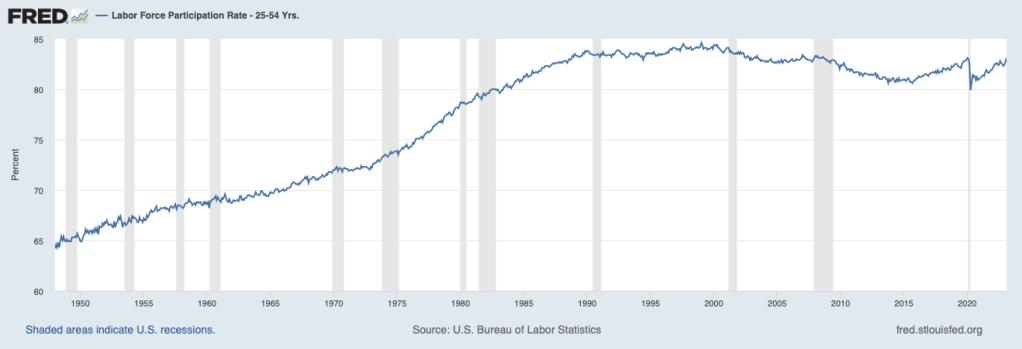

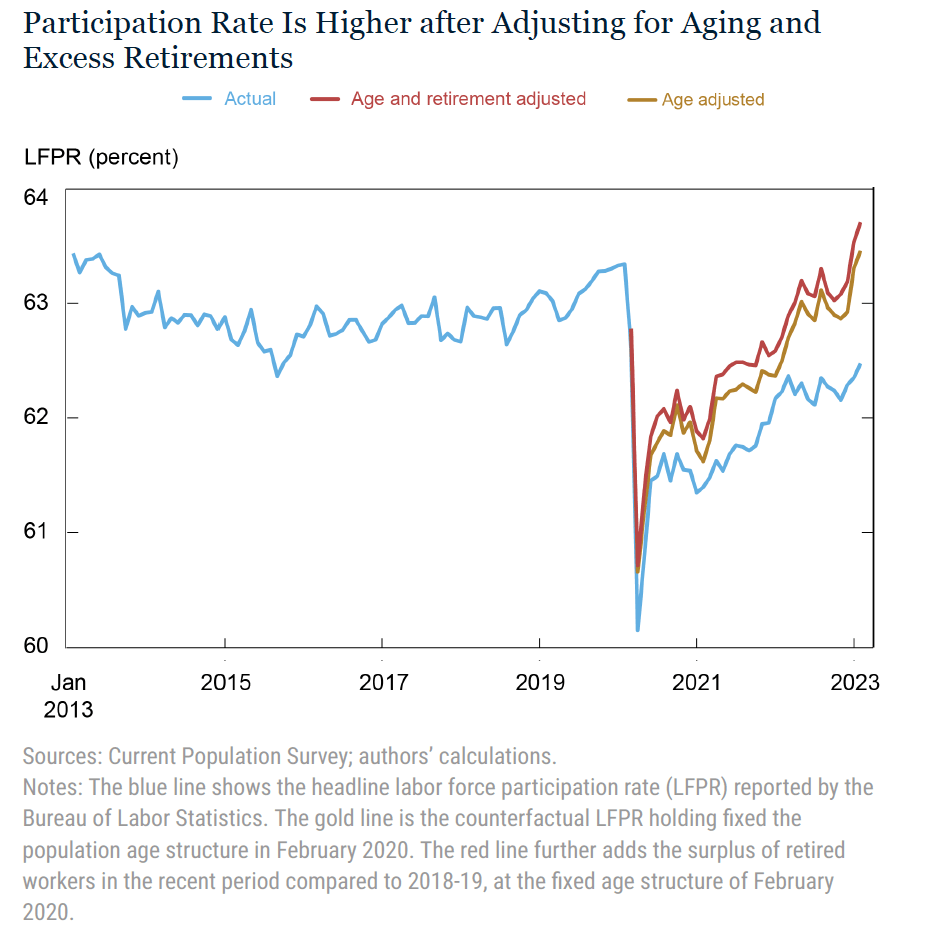

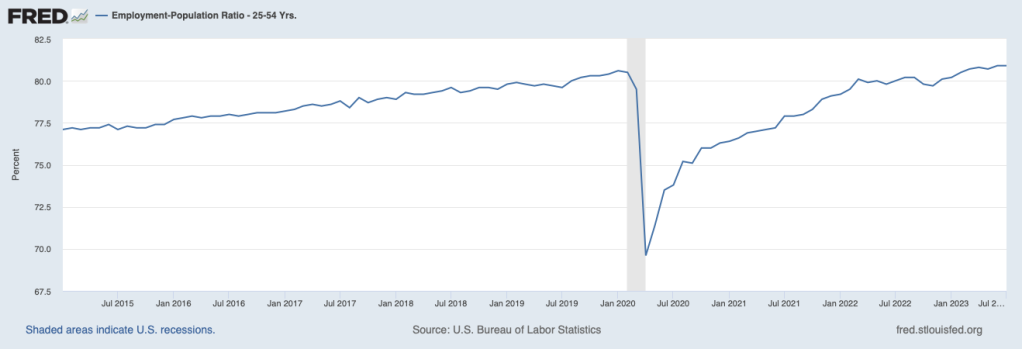

In his Jackson Hole speech, Powell noted that: “Labor supply has improved, driven by stronger participation among workers aged 25 to 54 and by an increase in immigration back toward pre-pandemic levels.” The following figure shows the employment-population ratio for people aged 25 to to 54—so-called prime-age workers. In July 2023, 80.9 percent of people in this age group were employed, actually above the ratio of 80.5 percent just before the pandemic. This increase in labor supply is another indication that the labor market disruptions caused by the pandemic has continued to ease, allowing for an increase in labor supply.

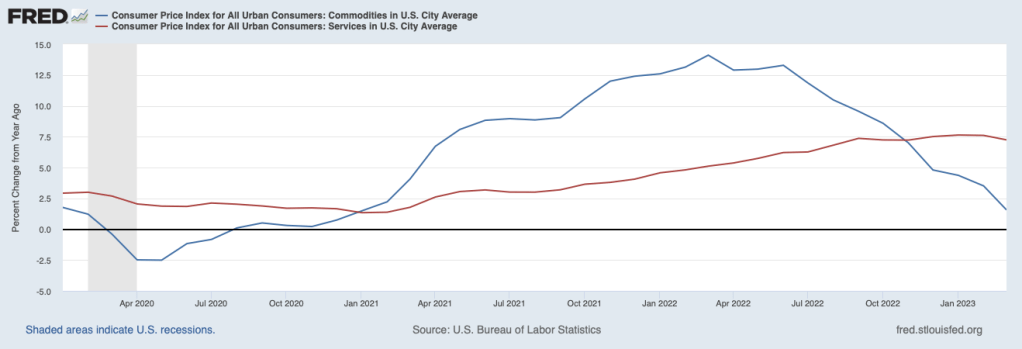

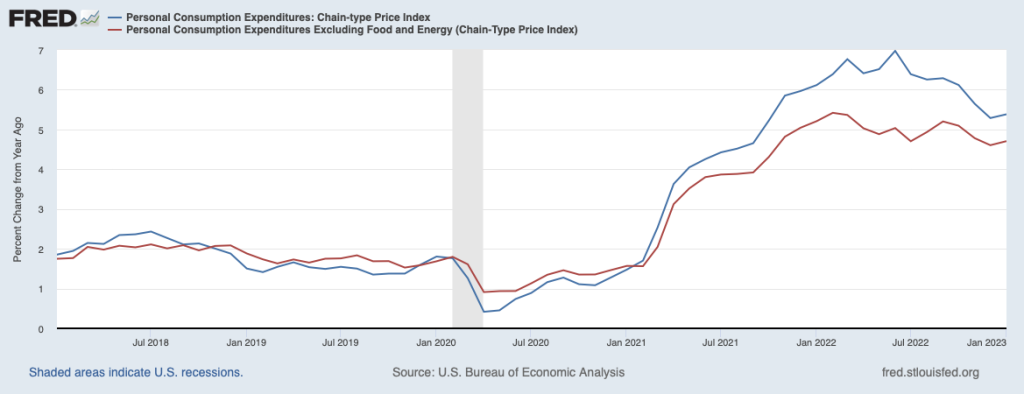

Taken together, these data indicate that labor market conditions are easing, likely reducing upward pressure on wages, and aiding the continuing decline in the inflation rate towards the Fed’s 2 percent target. Unless the data for August show an acceleration in inflation or a tightening of labor market conditions—which is certainly possible given what appears to be a strong expansion of real GDP during the third quarter—at its September meeting the Federal Open Market Committee is likely to keep its target for the federal funds rate unchanged.