Image created by ChatGPT

This morning (February 11), the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released its “Employment Situation” report (often called the “jobs report”) for January. The report was originally scheduled to be released last Friday but was postponed by the brief federal government shutdown. The data in the report show that the labor market was much stronger than expected in January.

The jobs report has two estimates of the change in employment during the month: one estimate from the establishment survey, often referred to as the payroll survey, and one from the household survey. As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 9, Section 9.1 (Economics, Chapter 19, Section 19.1), many economists and Federal Reserve policymakers believe that employment data from the establishment survey provide a more accurate indicator of the state of the labor market than do the household survey’s employment data and unemployment data. (The groups included in the employment estimates from the two surveys are somewhat different, as we discuss in this post.)

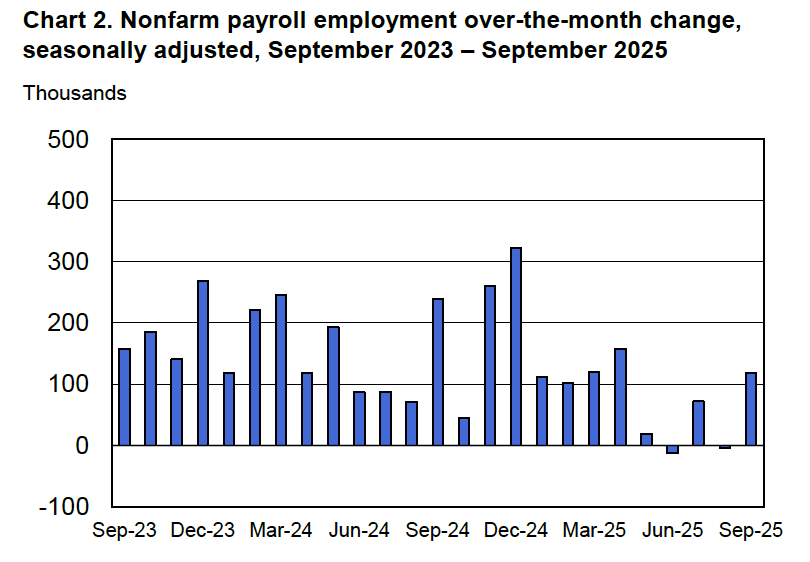

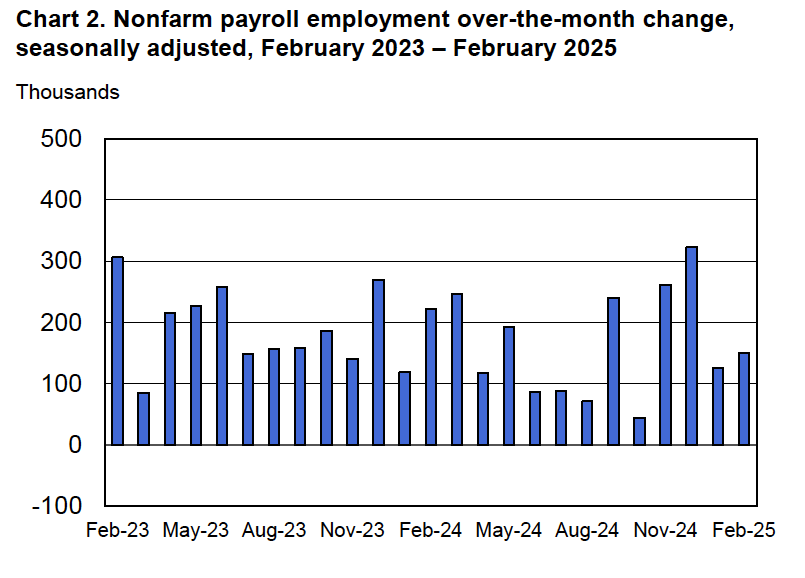

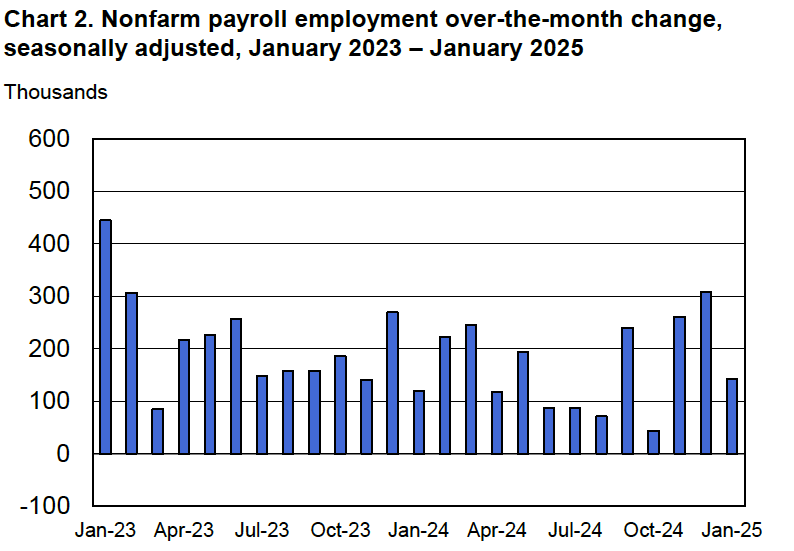

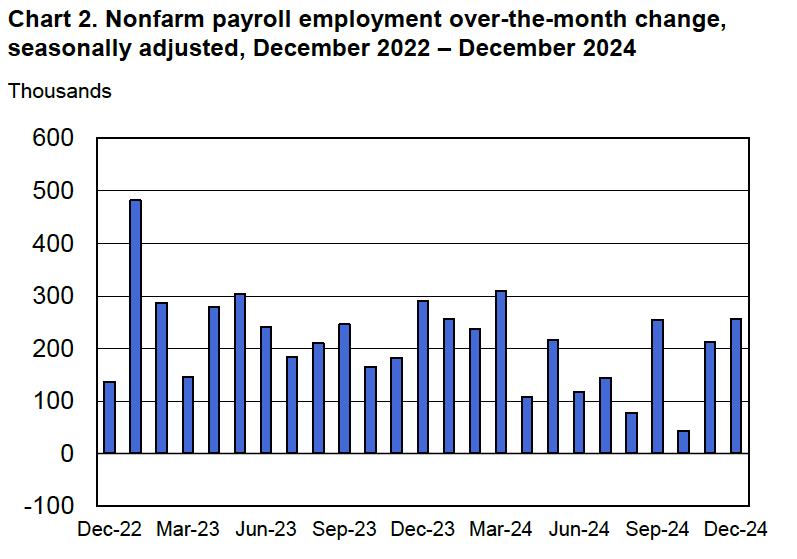

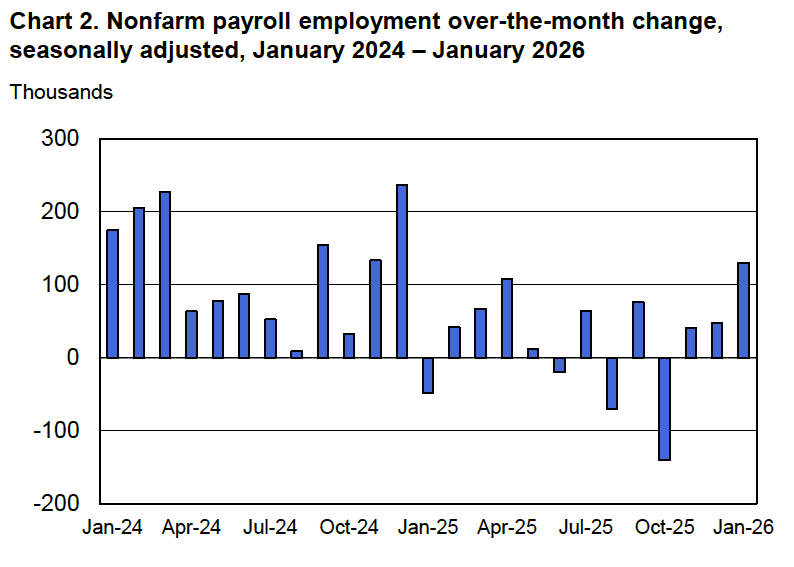

According to the establishment survey, there was a net increase of 130,000 nonfarm jobs during January. This increase was well above the increase of 55,000 that economists surveyed by the Wall Street Journal had forecast. Economists surveyed by Bloomberg had a higher forecast of 65,000 net jobs. The BLS revised downward its previous estimates of employment in November and December by a combined 17,000 jobs. (The BLS notes that: “Monthly revisions result from additional reports received from businesses and government agencies since the last published estimates and from the recalculation of seasonal factors.”)

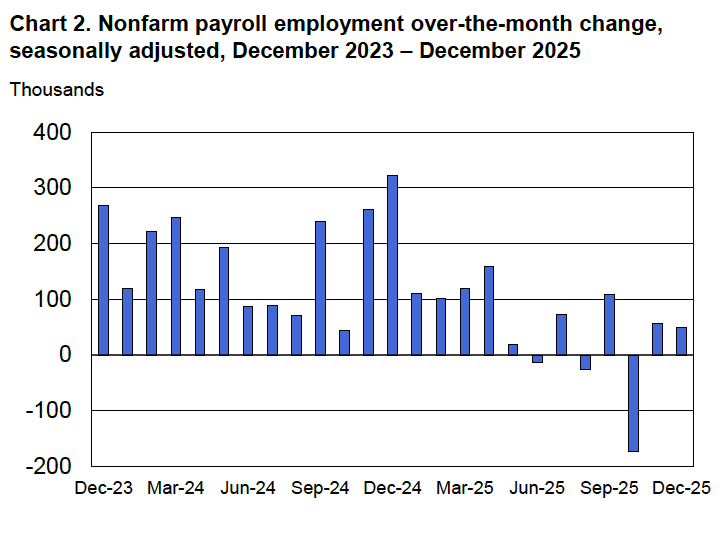

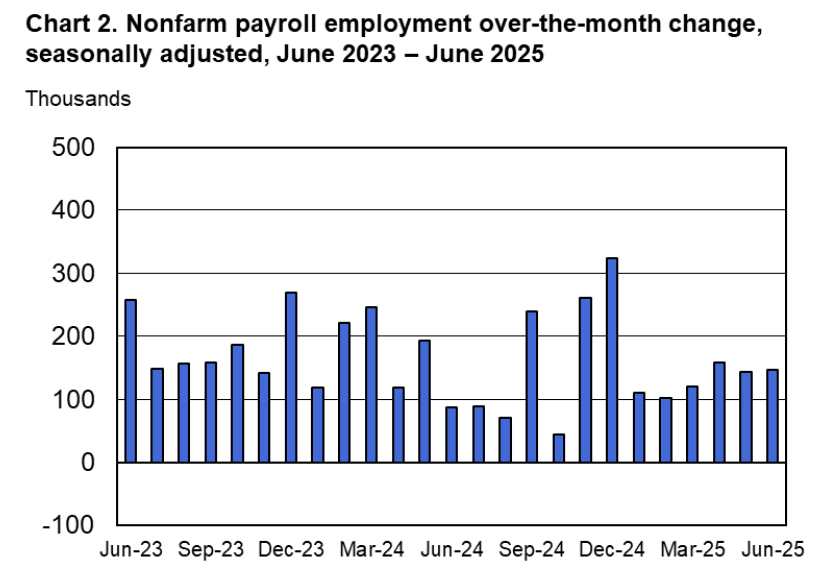

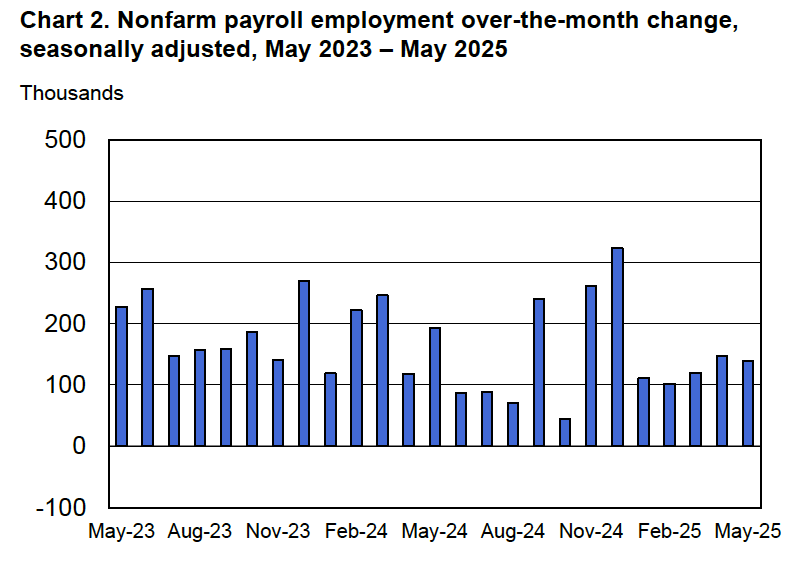

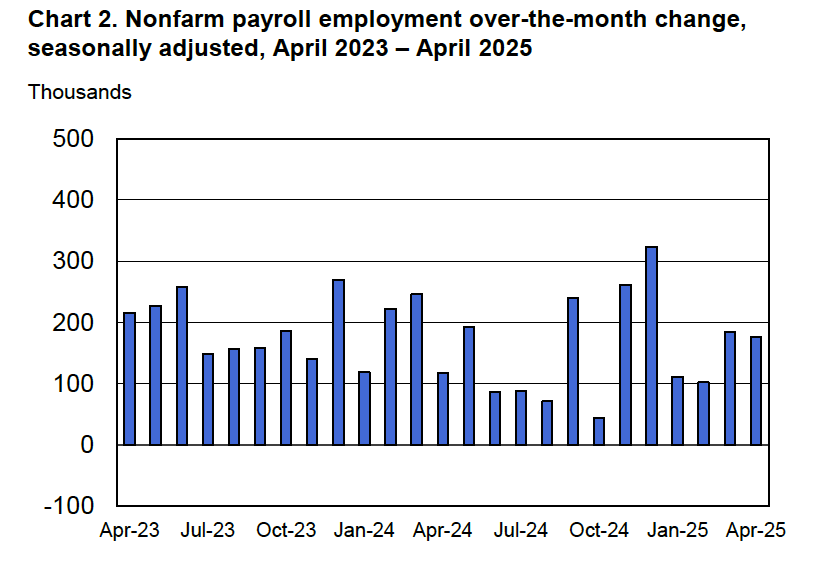

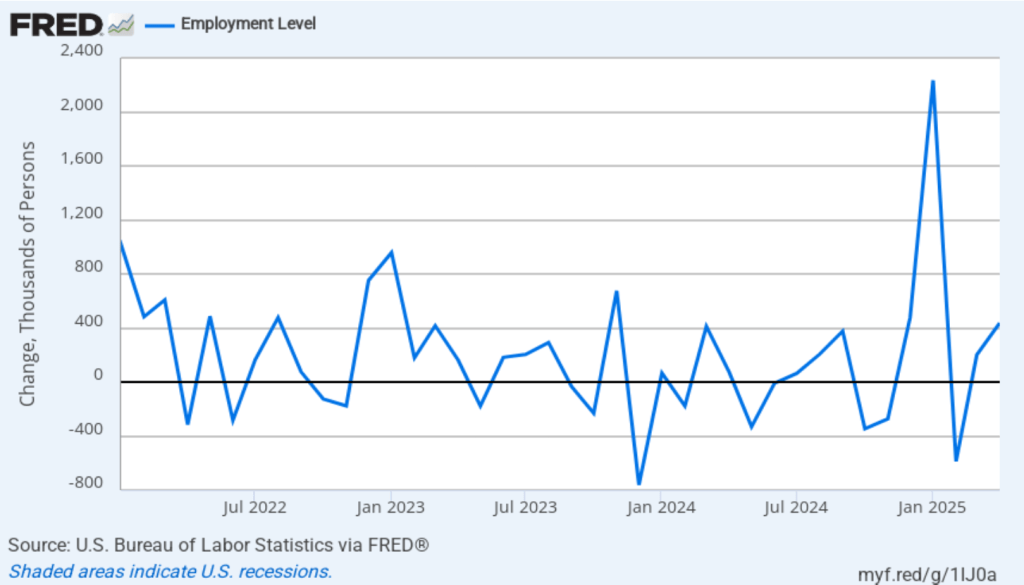

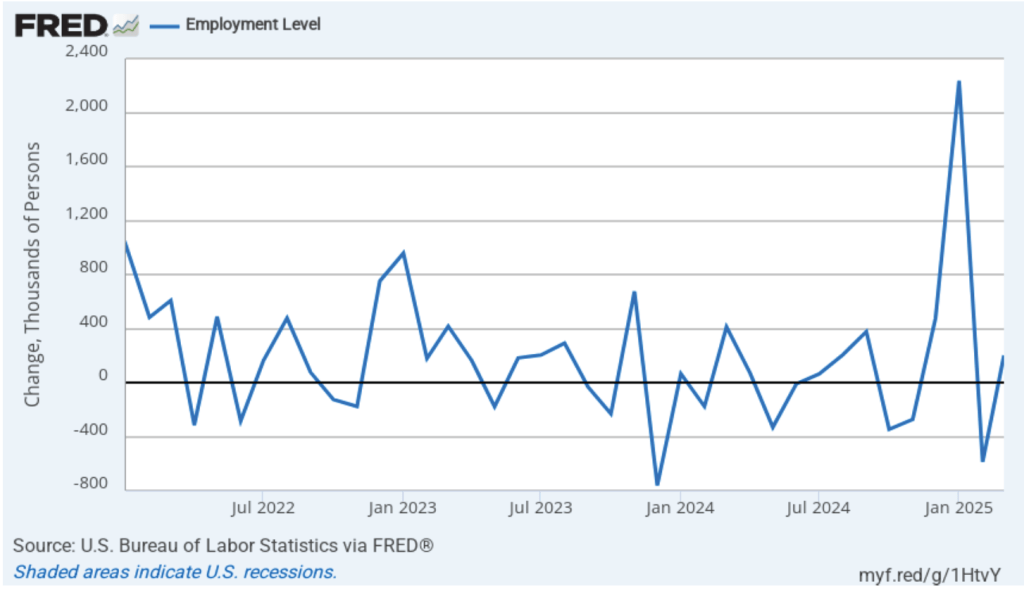

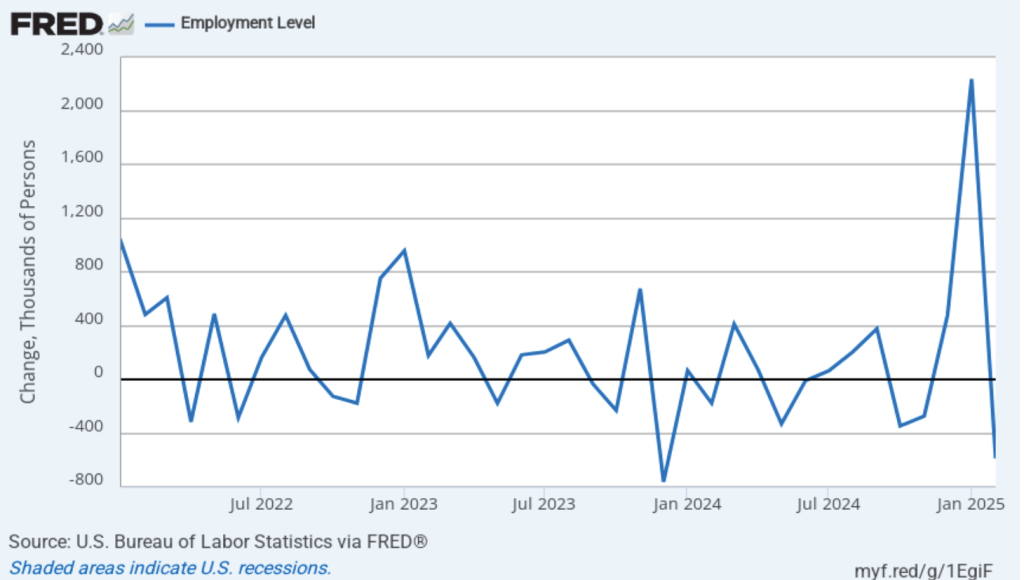

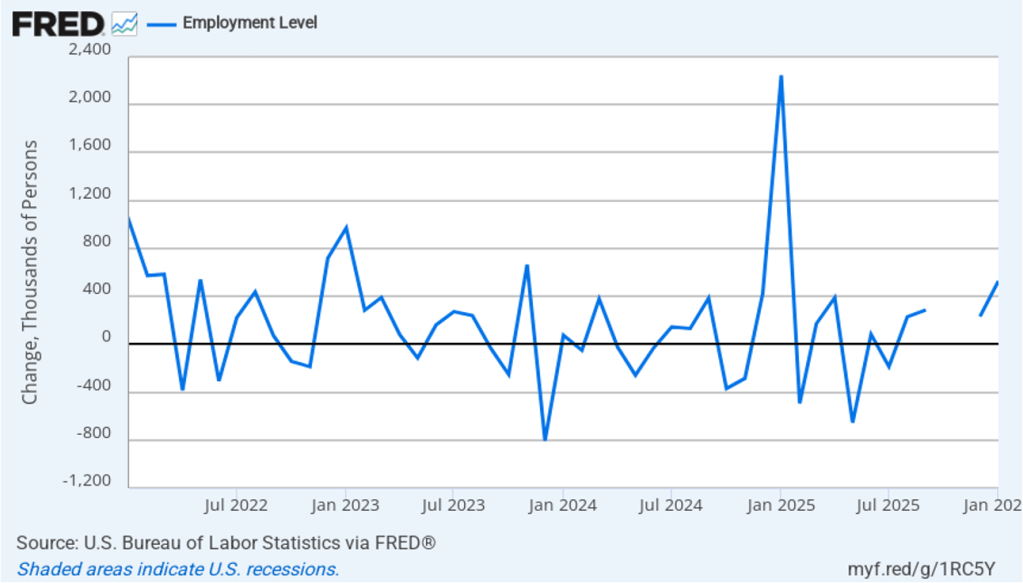

The following figure from the jobs report shows the net change in nonfarm payroll employment for each month in the last two years. The increase in net jobs in January was the largest since December 2024.

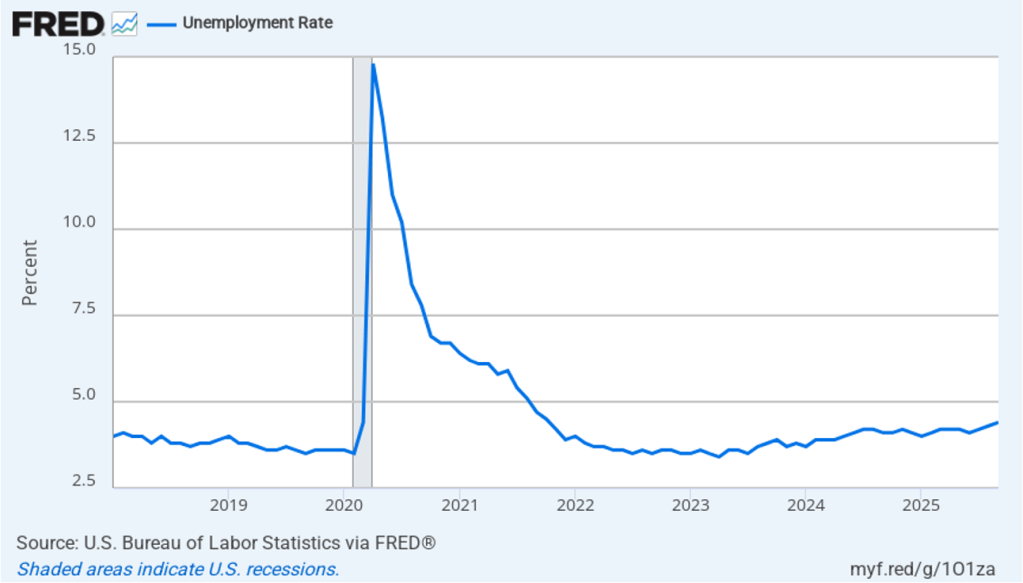

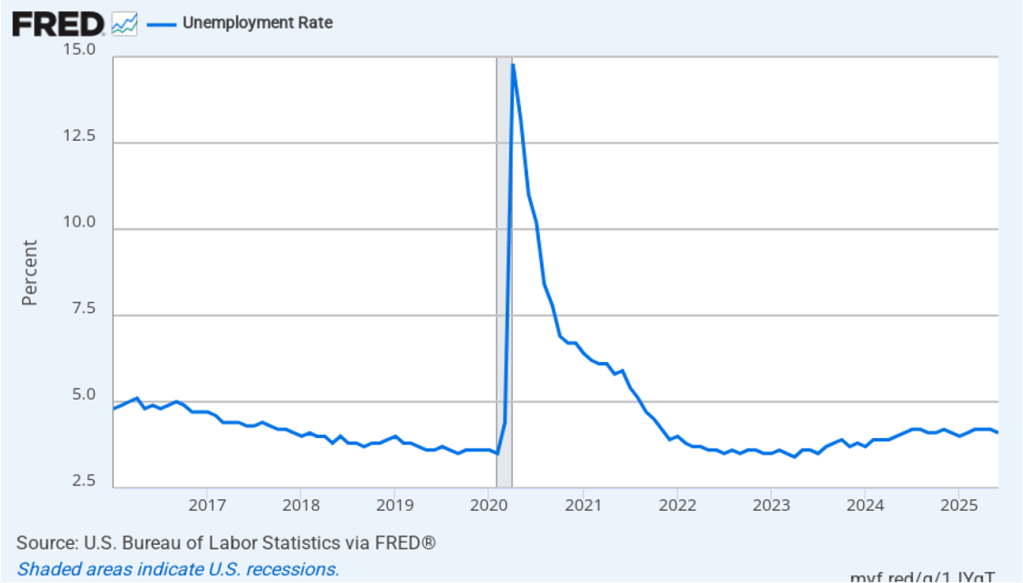

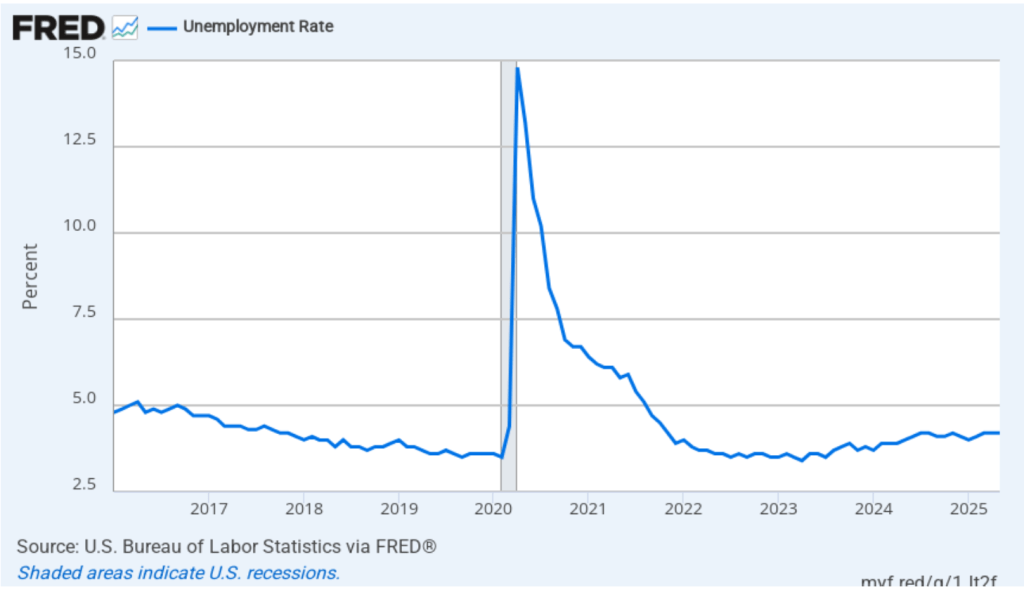

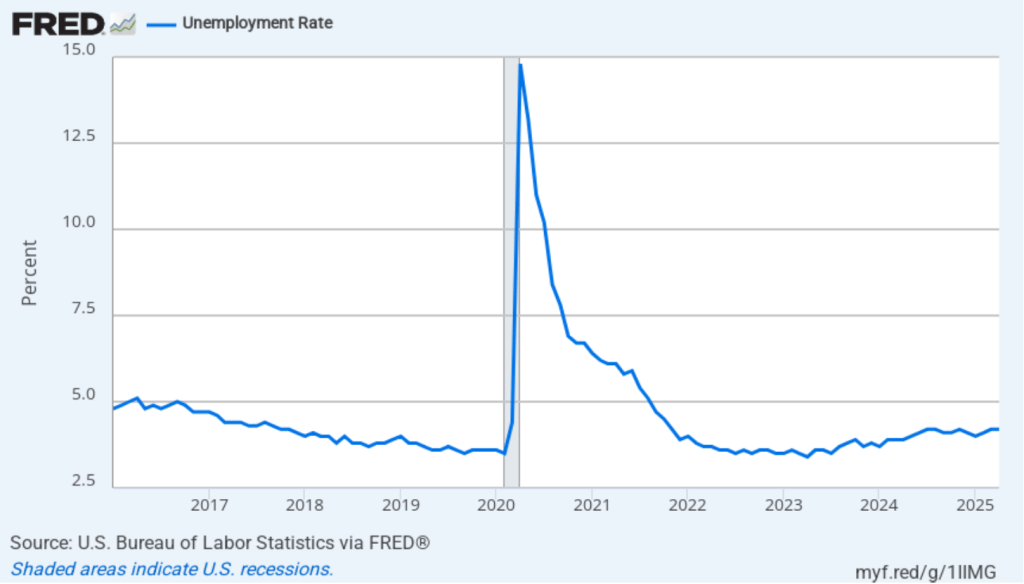

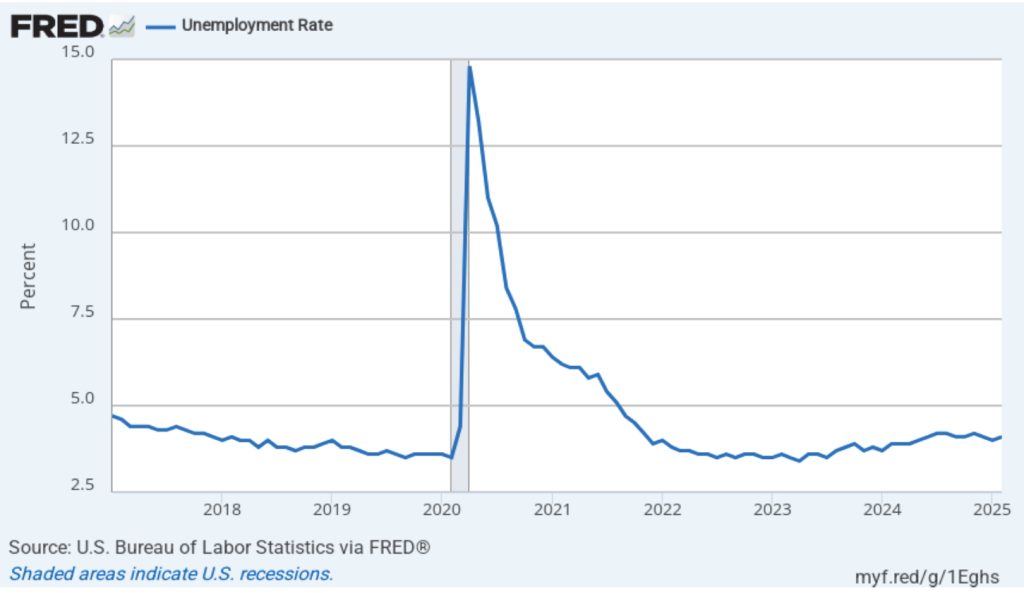

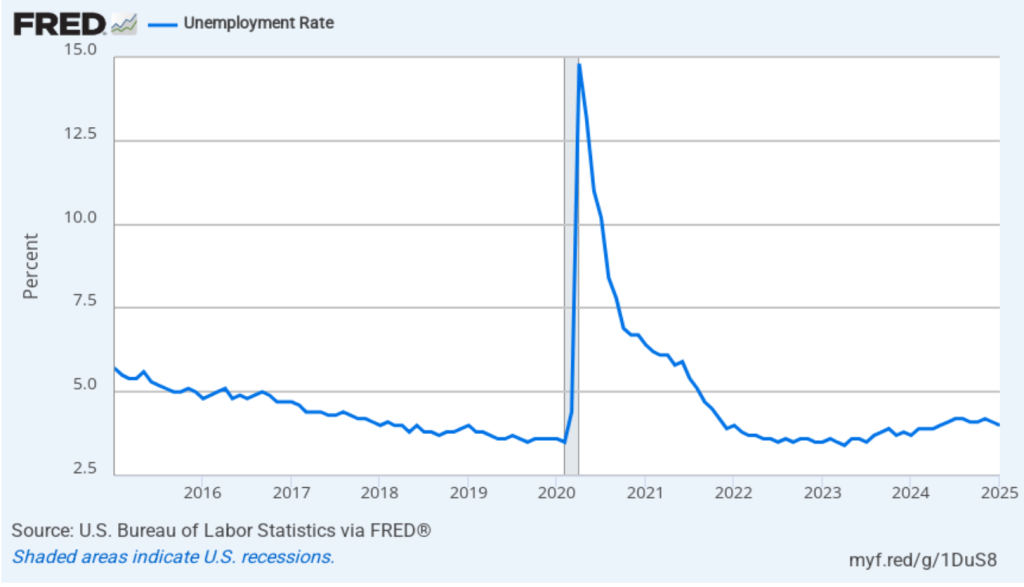

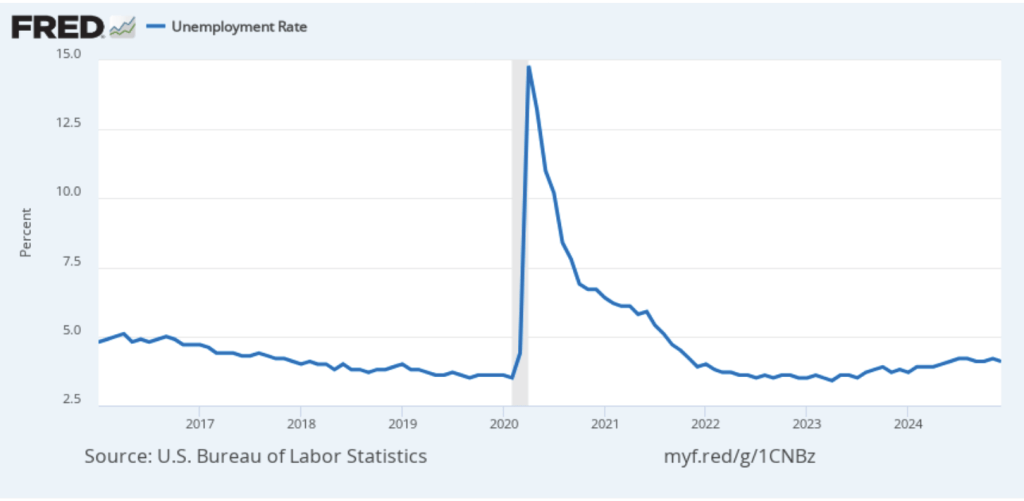

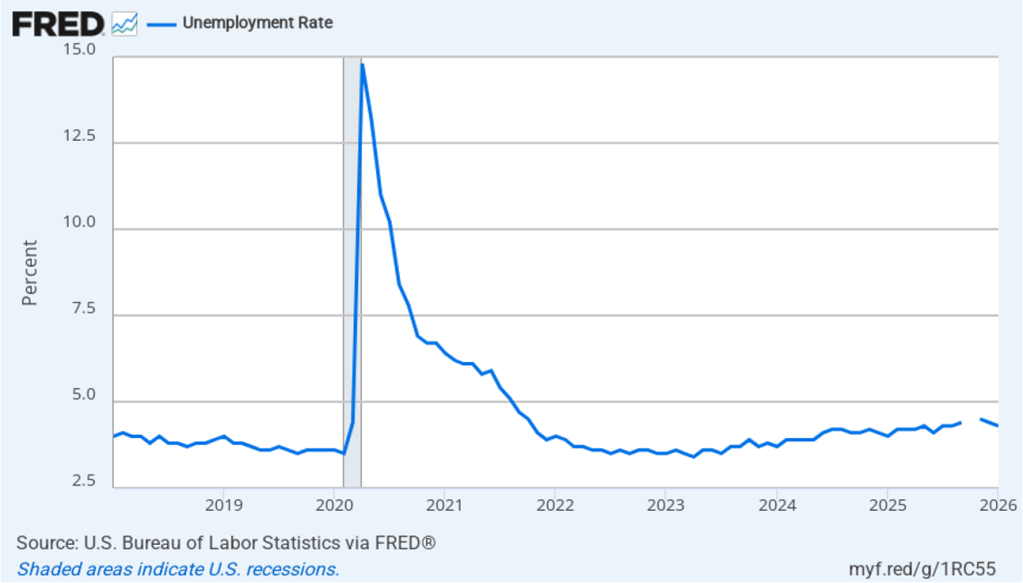

The unemployment rate, which is calculated from data in the household survey, fell from 4.4 percent in December to 4.3 percent in January. As the following figure shows, the unemployment rate has been remarkably stable over the past year and a half, staying between 4.0 percent and 4.4 percent in each month since May 2024. The Federal Open Market Committee’s current estimate of the natural rate of unemployment—the normal rate of unemployment over the long run—is 4.2 percent. So, unemployment is slightly above the natural rate. (We discuss the natural rate of unemployment in Macroeconomics, Chapter 9 and Economics, Chapter 19.)

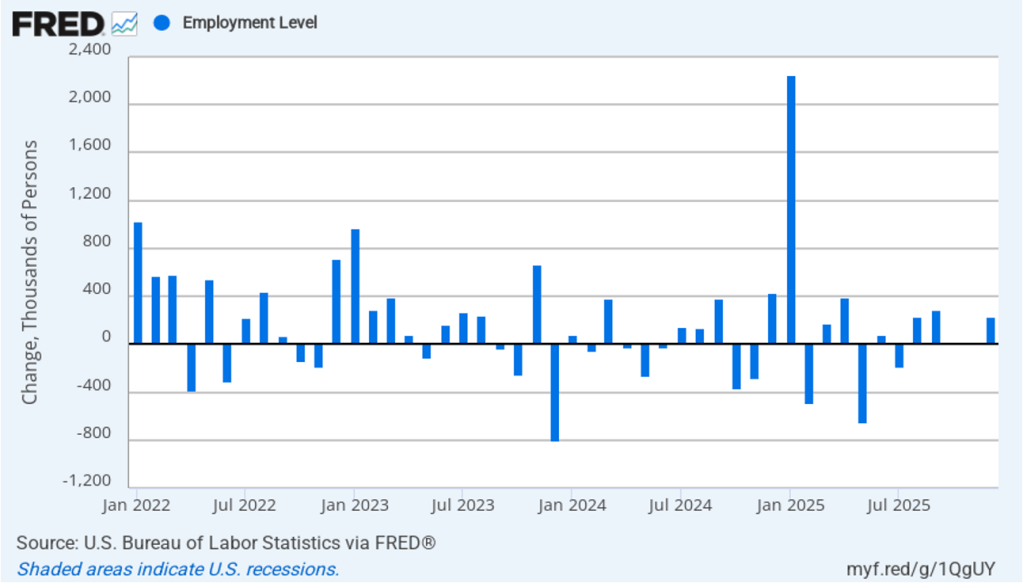

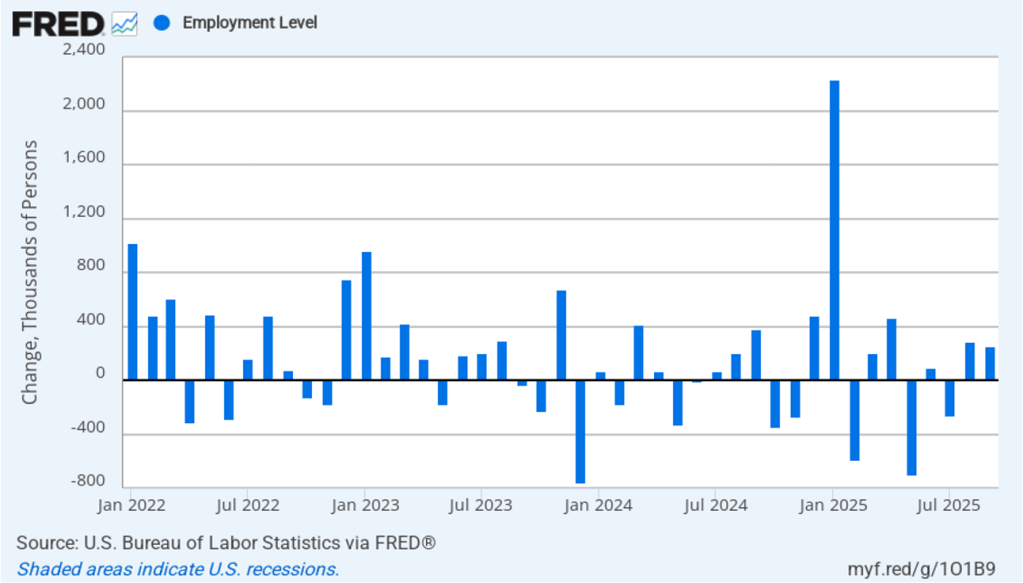

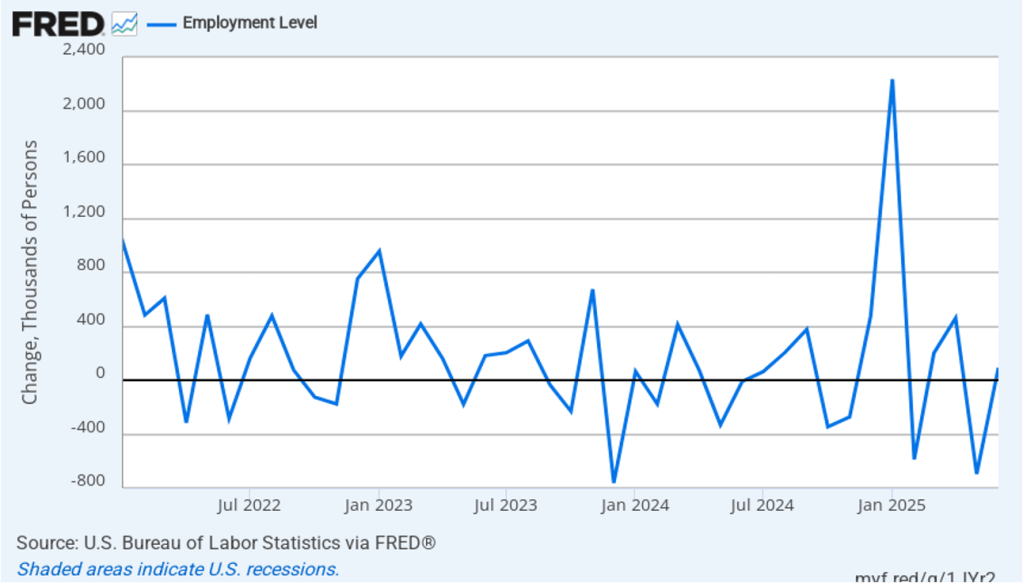

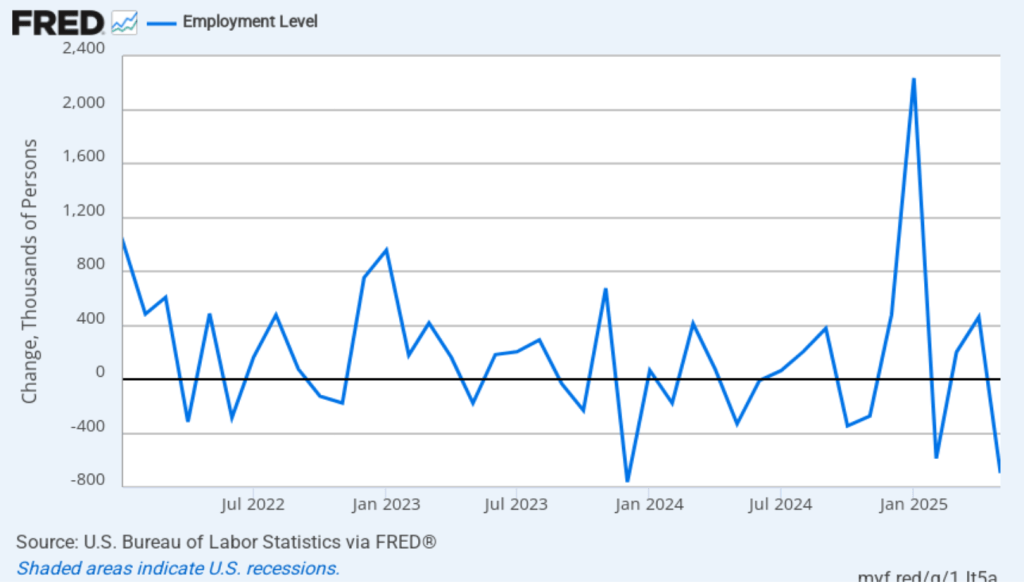

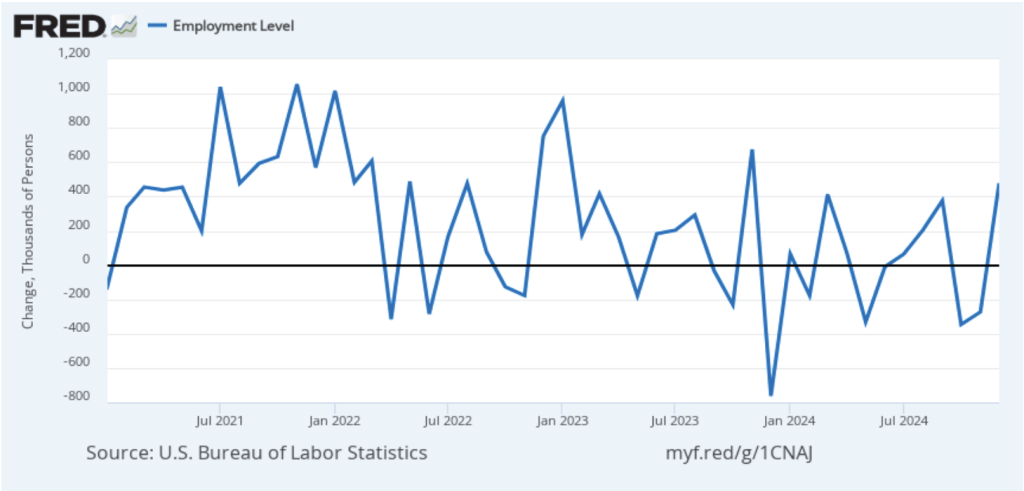

As the following figure shows, the monthly net change in jobs from the household survey moves much more erratically than does the net change in jobs from the establishment survey. As measured by the household survey, there was a net increase of 528,000 in January, far above the increase in jobs from the payroll survey. (Note that because of last year’s shutdown of the federal government, there are no data for October or November.) In any particular month, the story told by the two surveys can be inconsistent. In this case, both surveys indicate unexpectedly strong job growth, with the increase in household employment being particularly strong. (In this blog post, we discuss the differences between the employment estimates in the two surveys.)

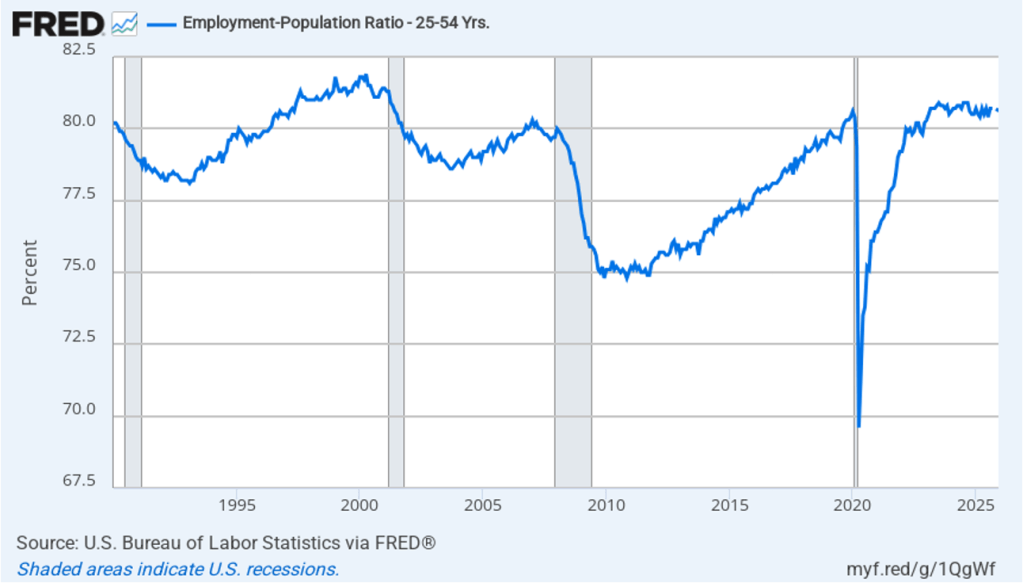

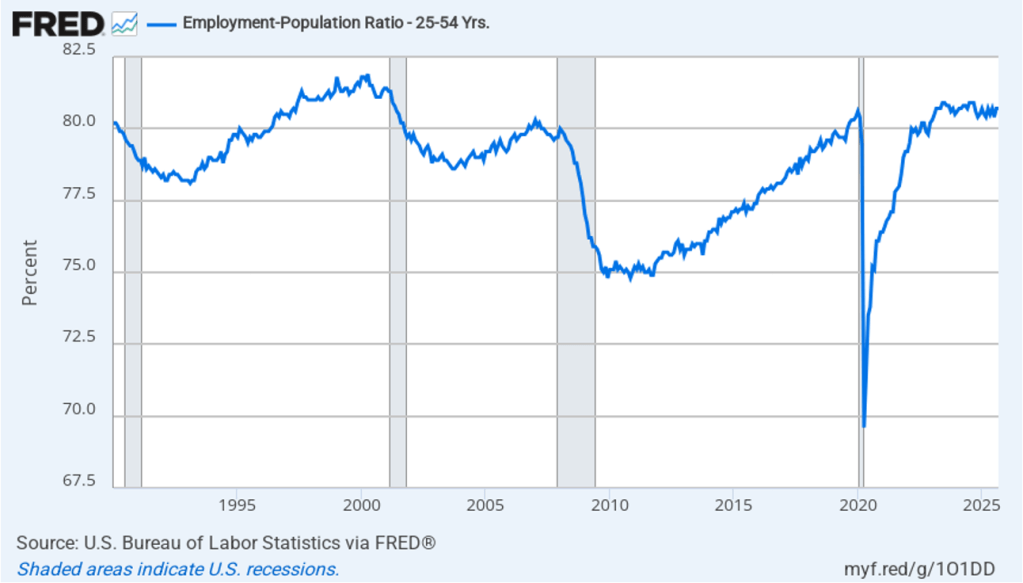

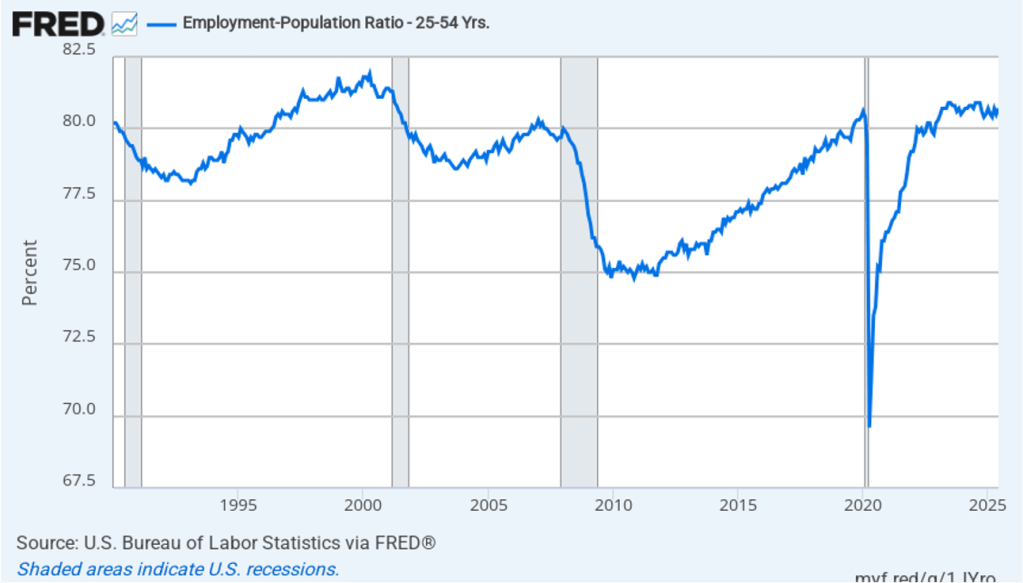

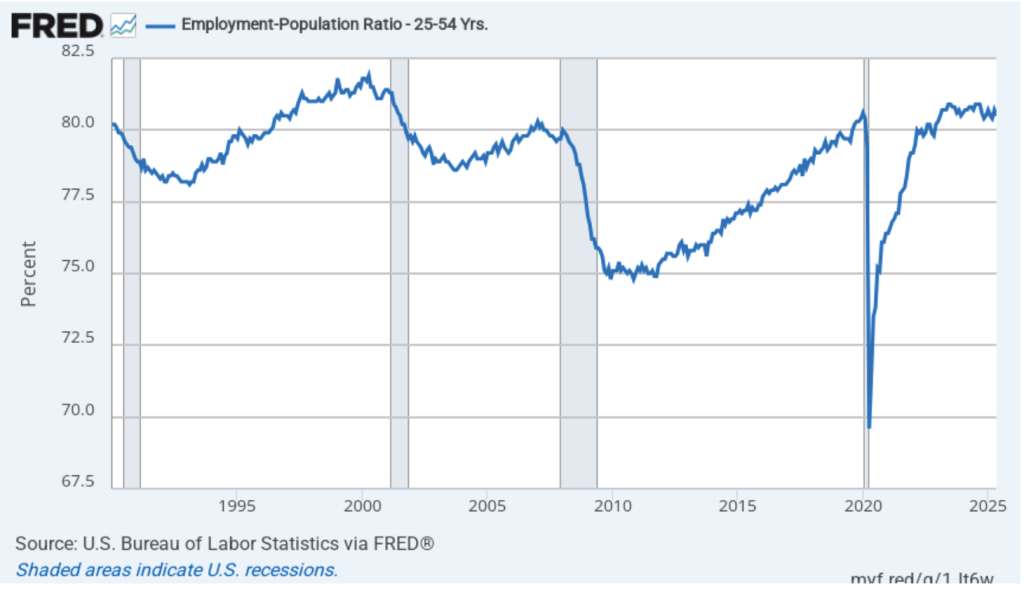

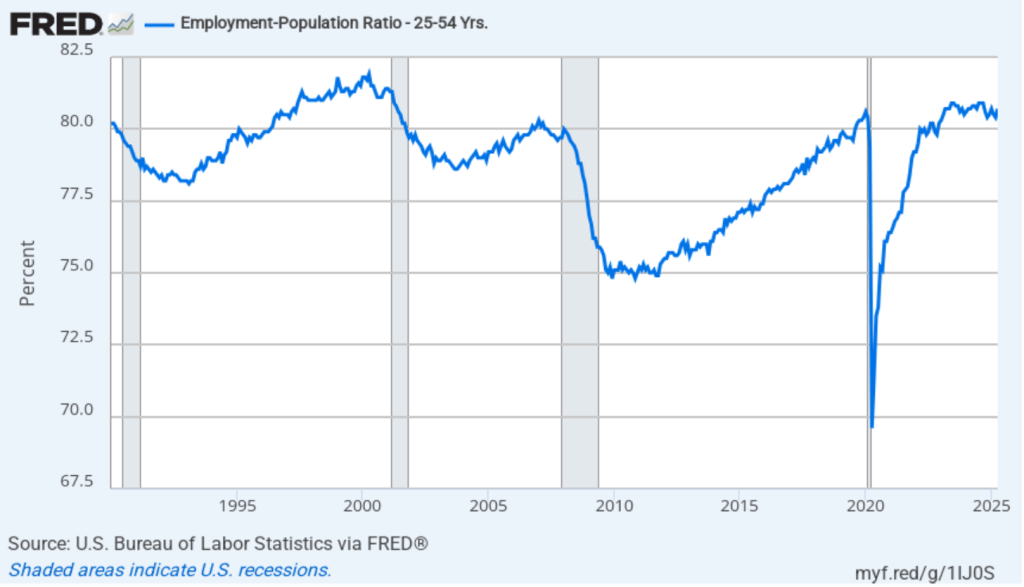

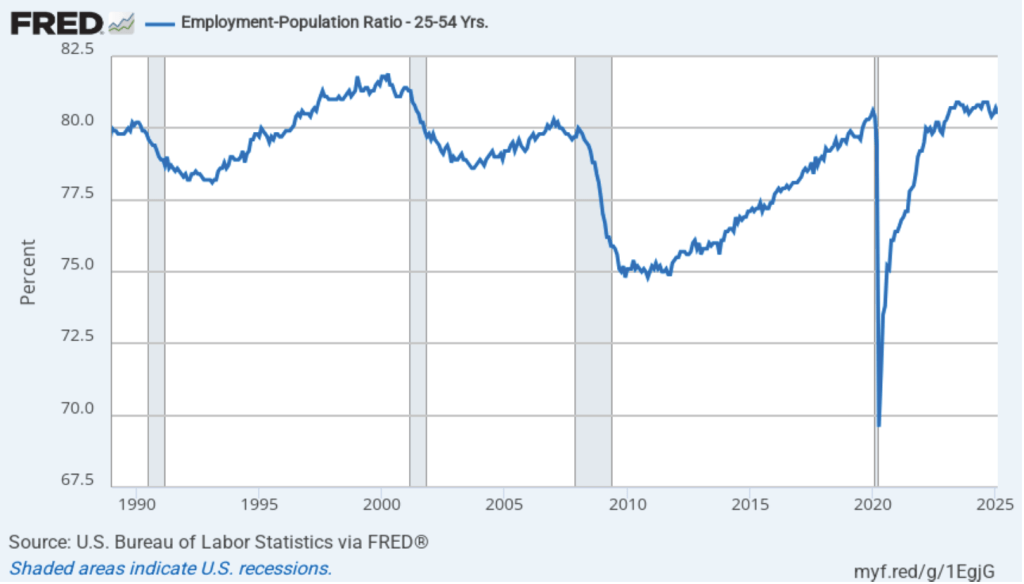

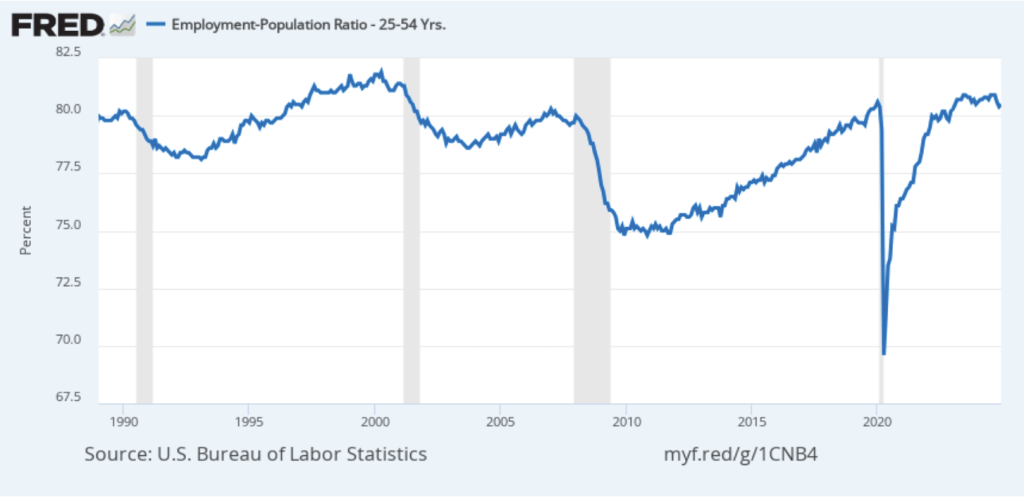

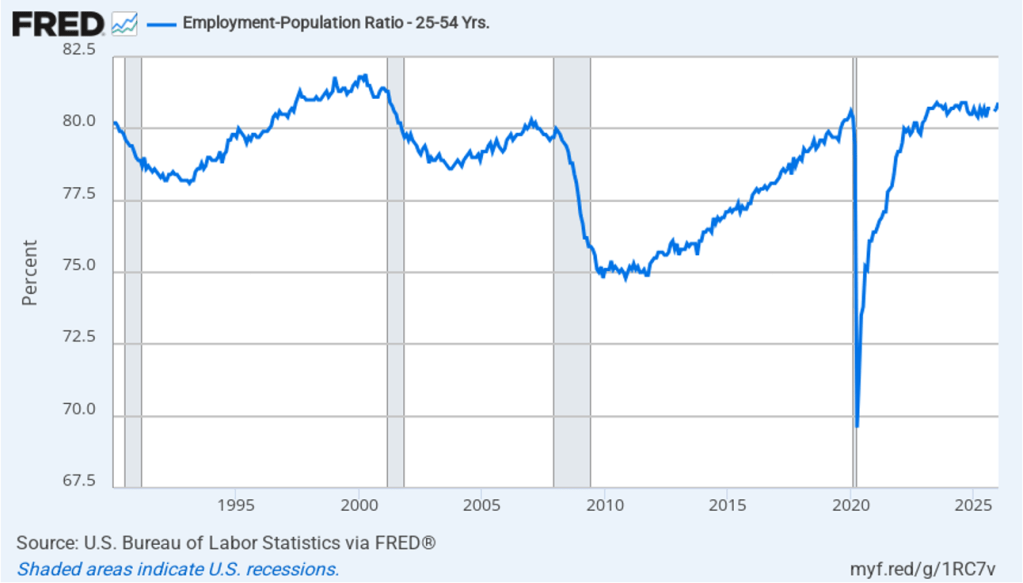

The household survey has another important labor market indicator: the employment-population ratio for prime age workers—those workers aged 25 to 54. In January the ratio was 80.9 percent, the highest since September 2024. In addition to matching the recent highs reached in mid-2024, the prime-age employment-population ratio is above what the ratio was in any month since April 2001. The continued high levels of the prime-age employment-population ratio indicates some continuing strength in the labor market.

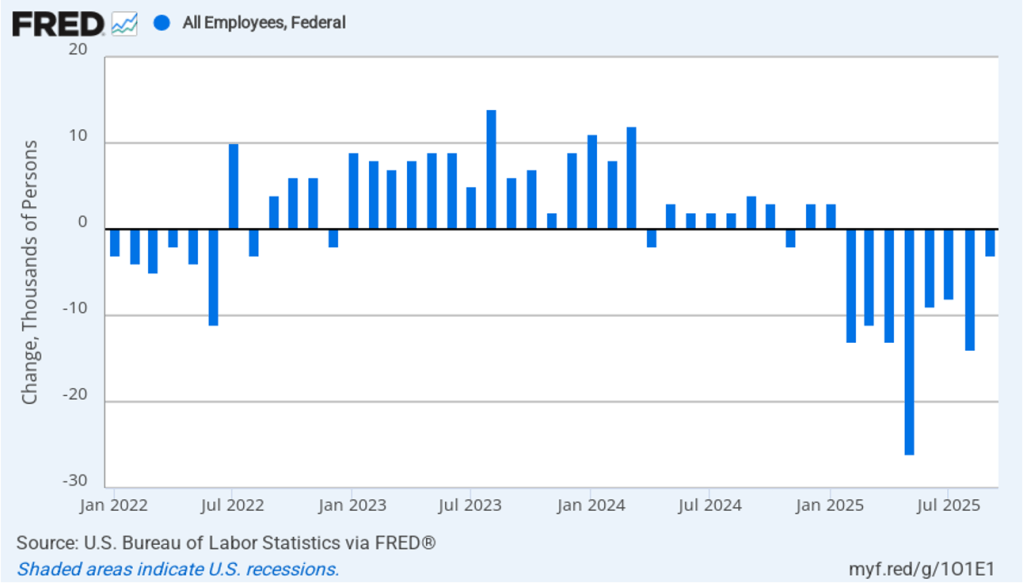

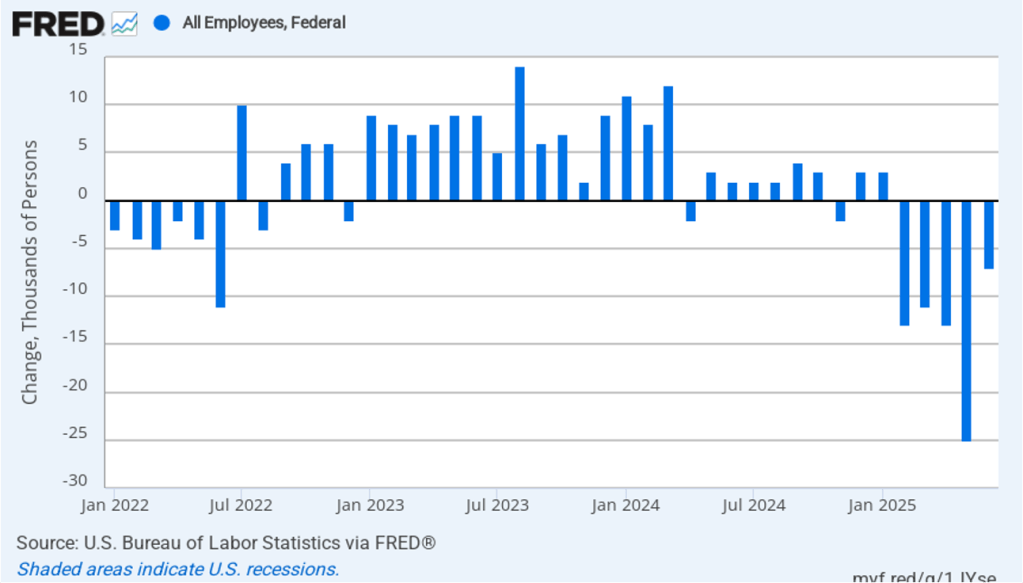

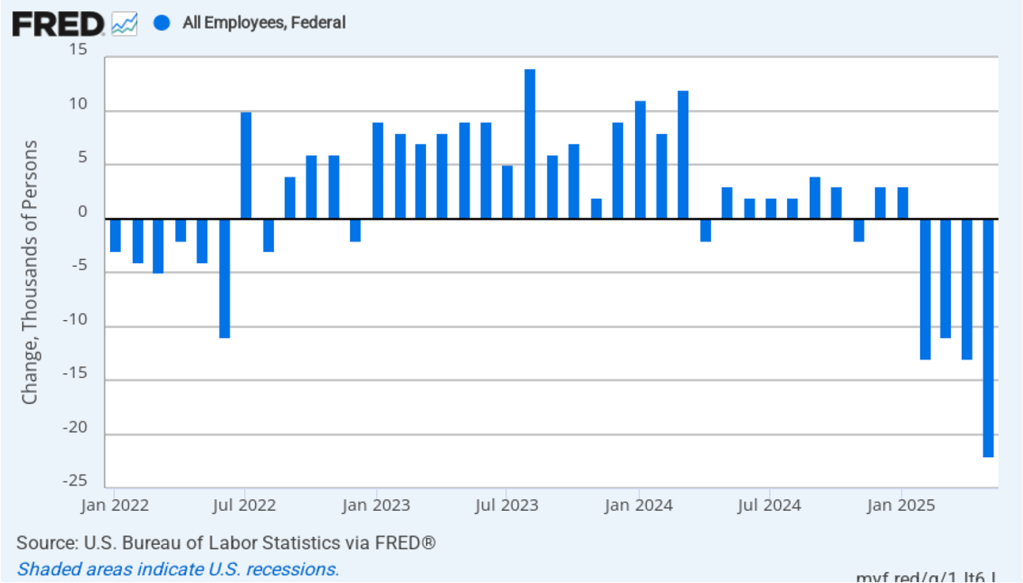

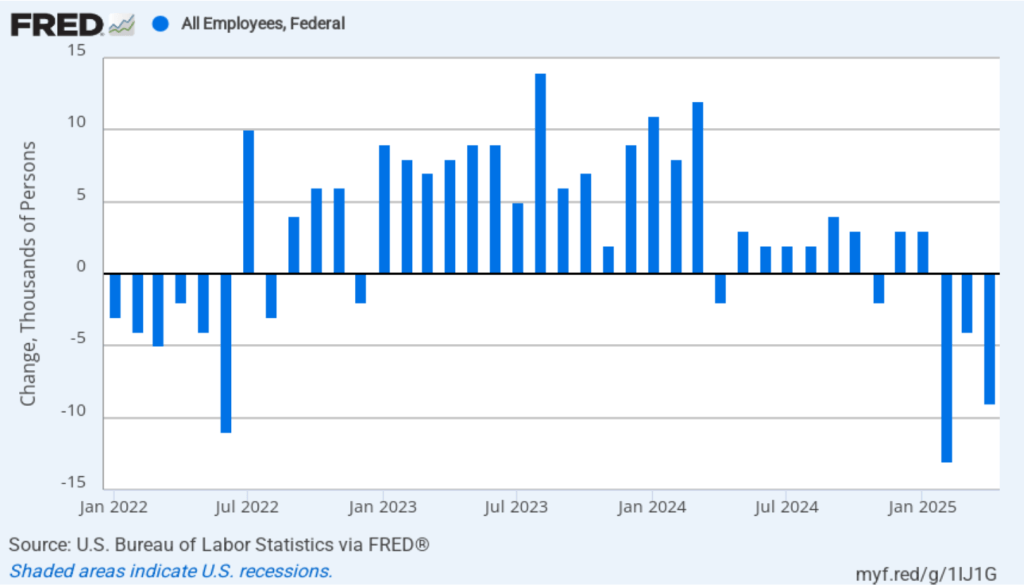

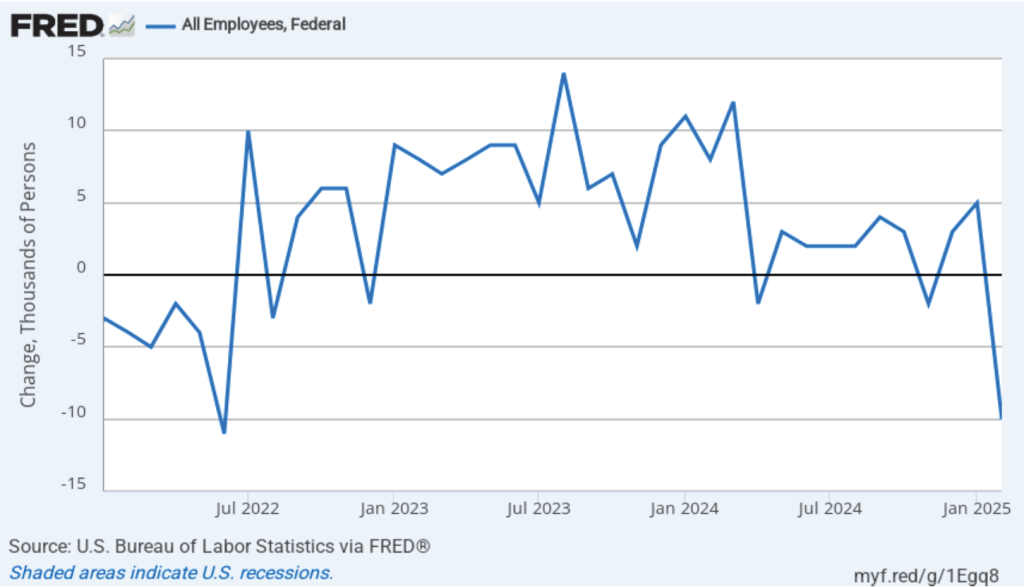

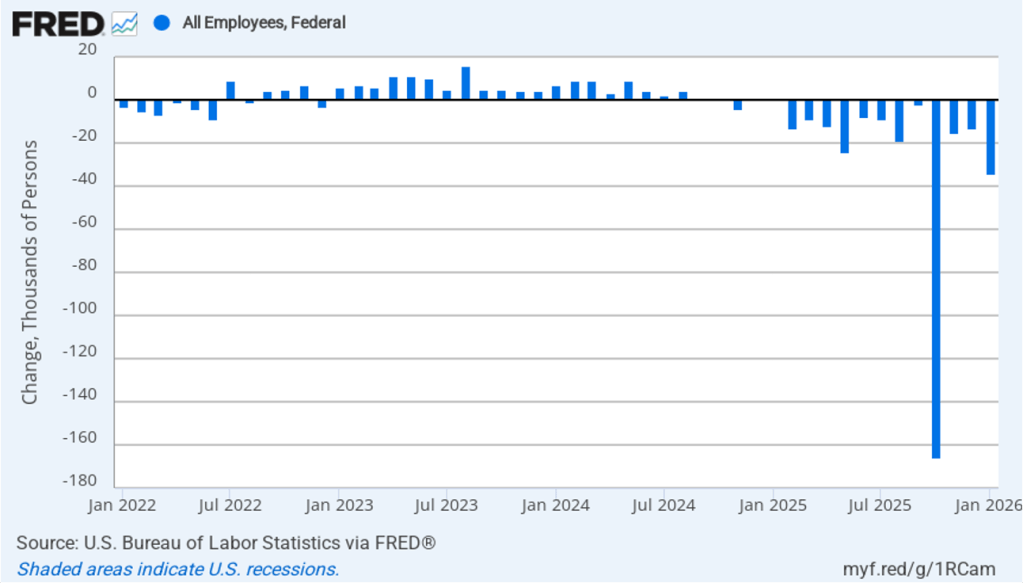

The Trump Administration’s layoffs of some federal government workers are clearly shown in the estimate of total federal employment for October, when many federal government employees exhausted their severance pay. (The BLS notes that: “Employees on paid leave or receiving ongoing severance pay are counted as employed in the establishment survey.”) As the following figure shows, there was a decline federal government employment of 166,000 in October, with additional declines in the following three months. The total decline in federal government employment since the beginning of February 2025 is 324,000.

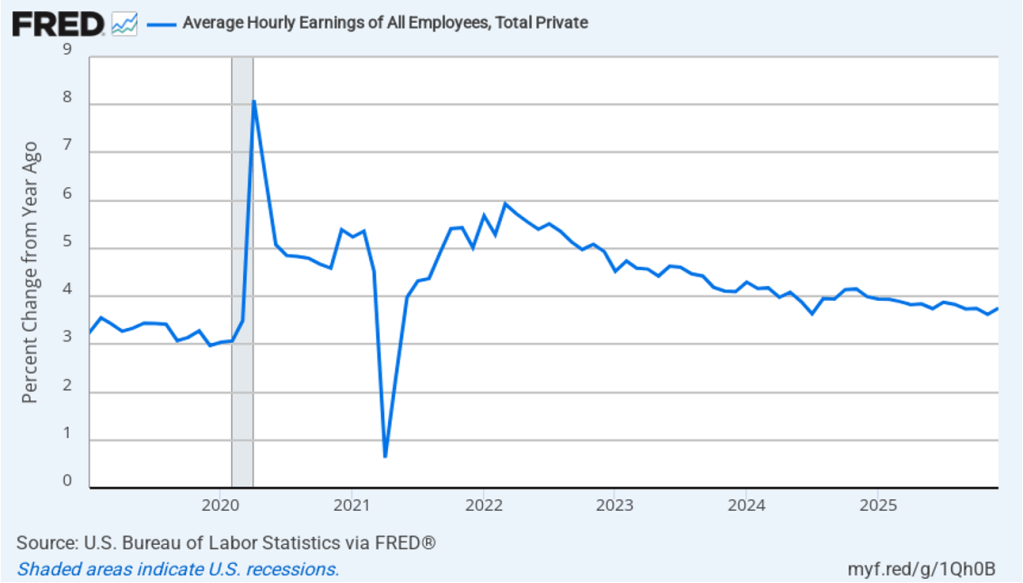

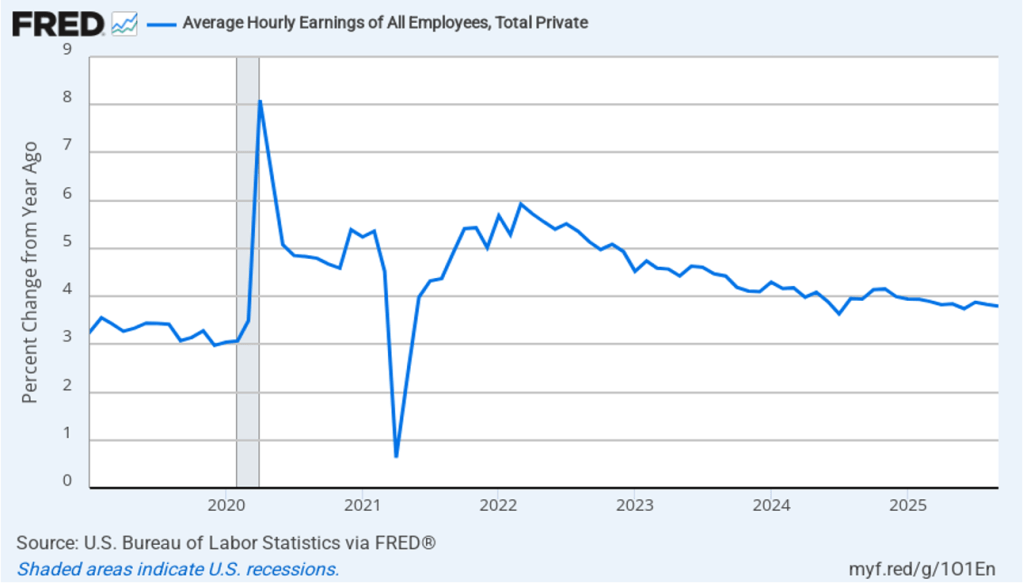

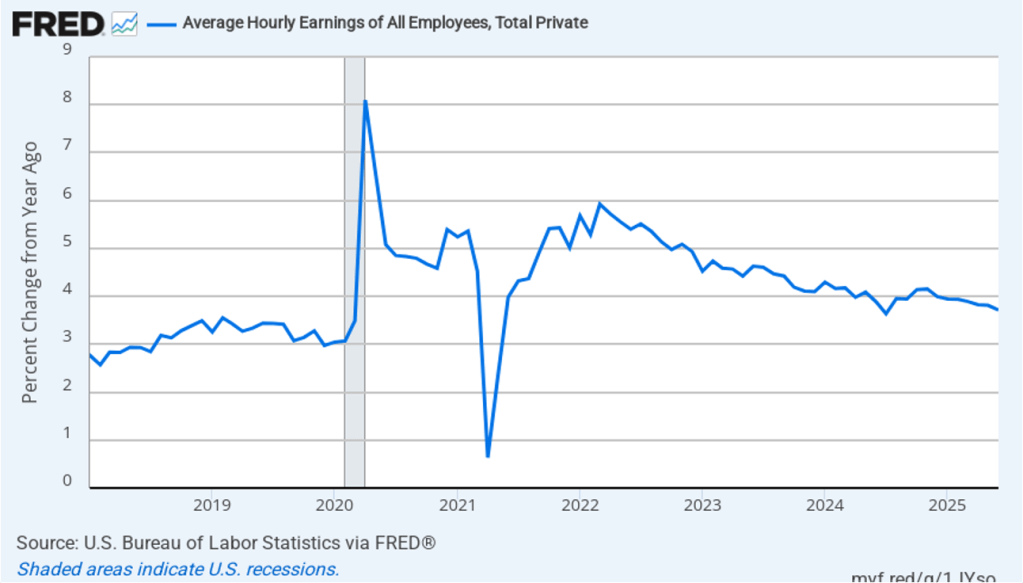

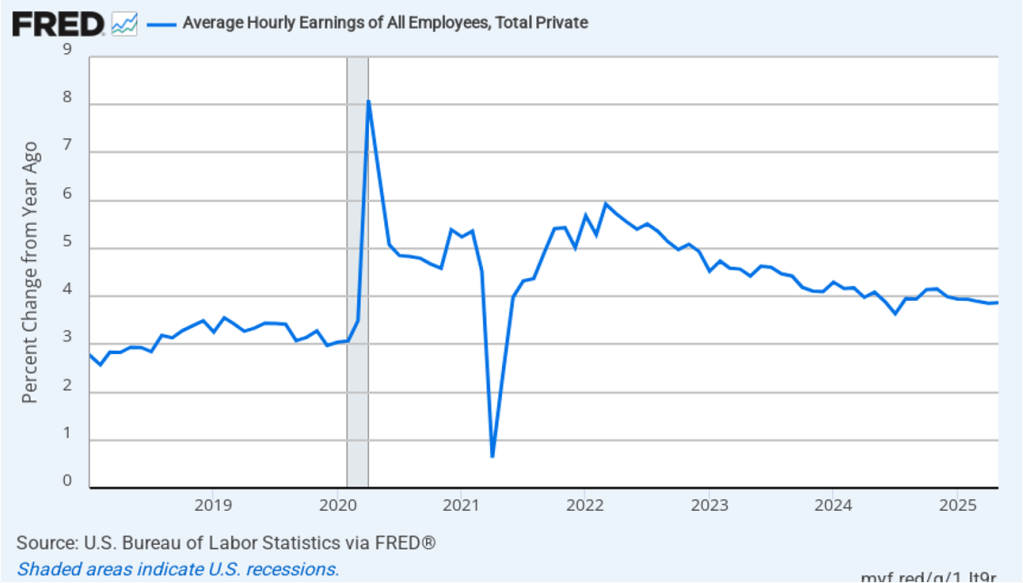

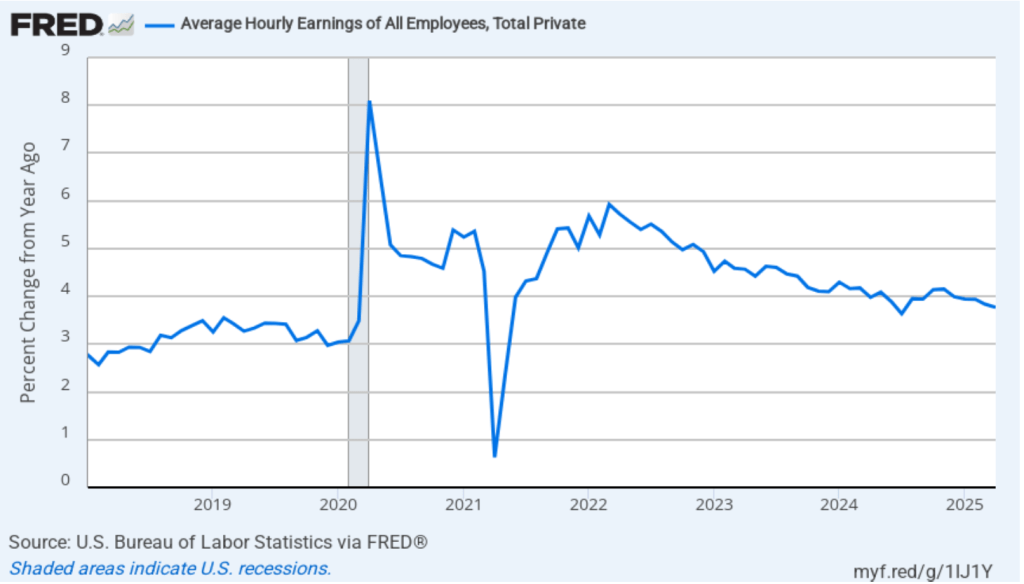

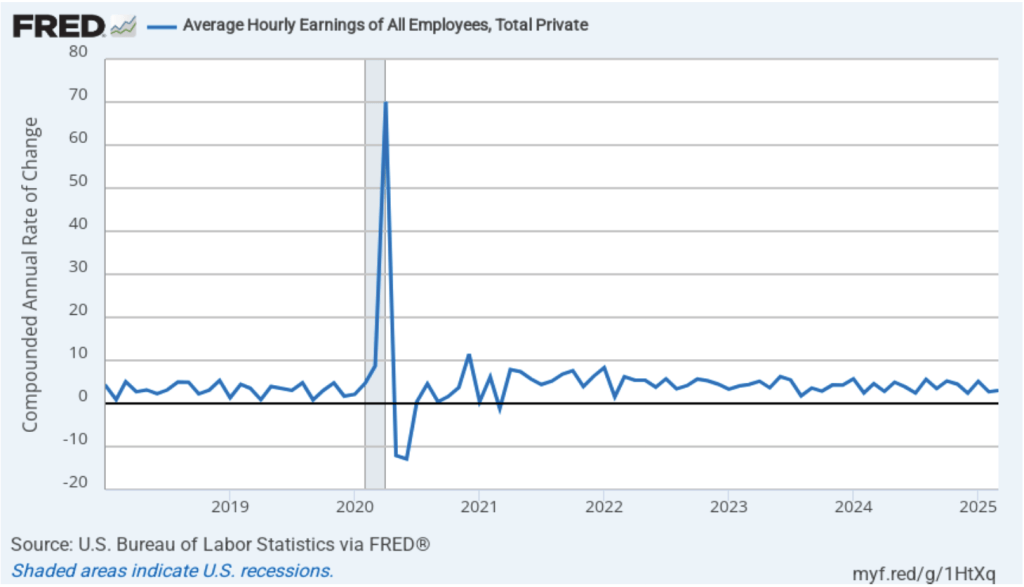

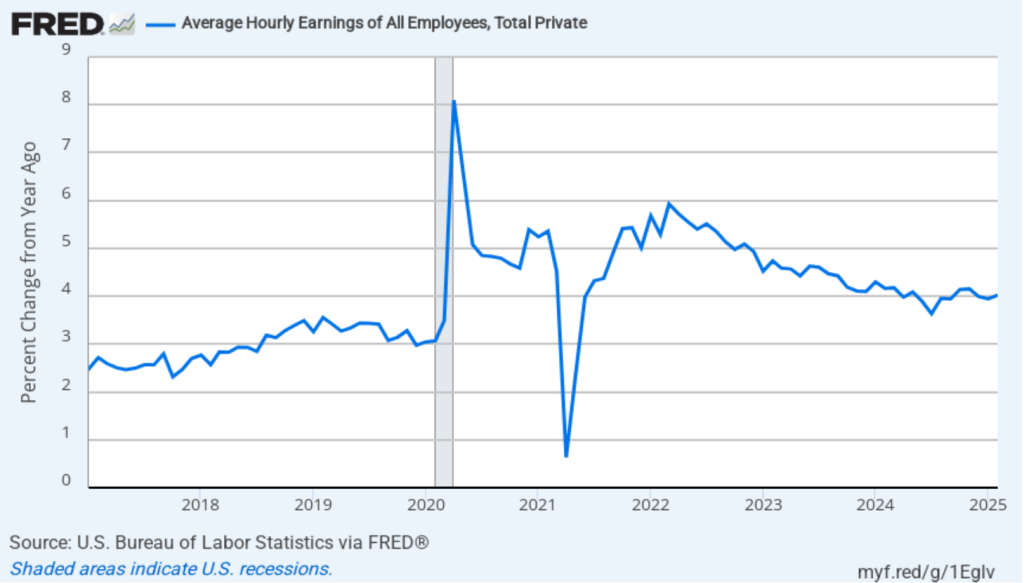

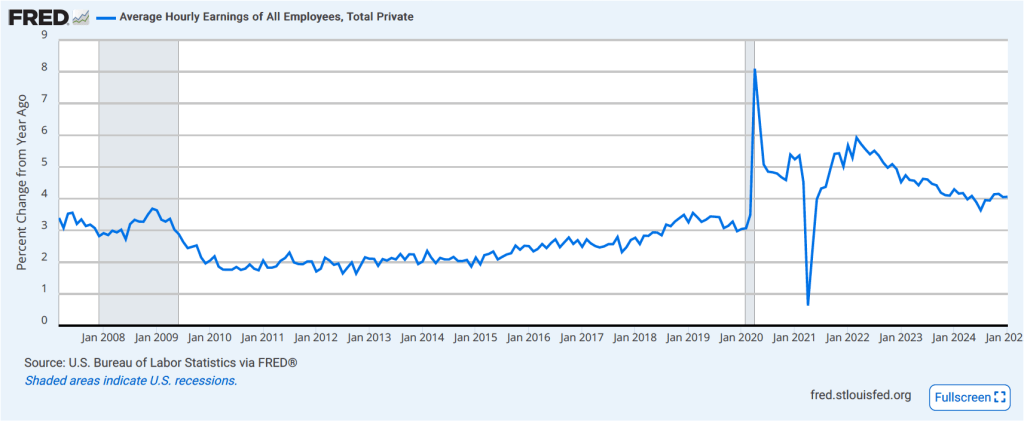

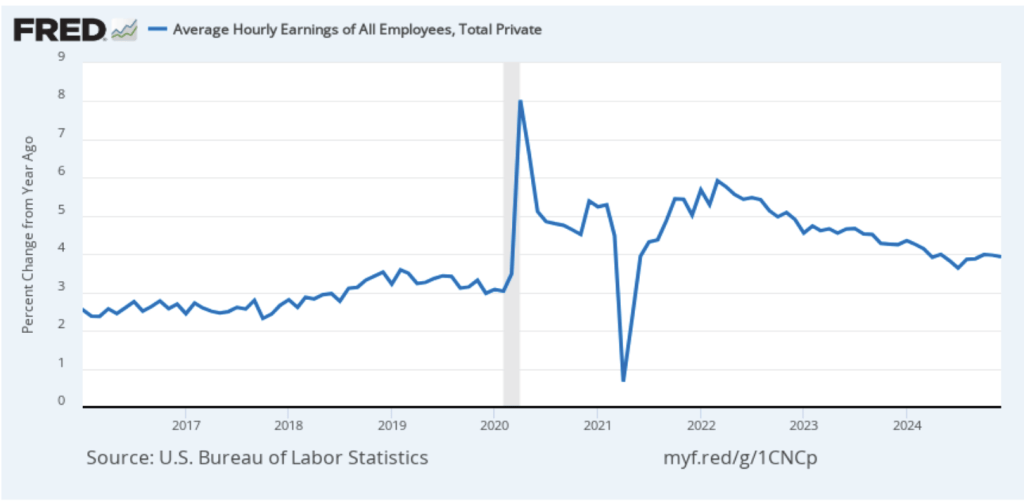

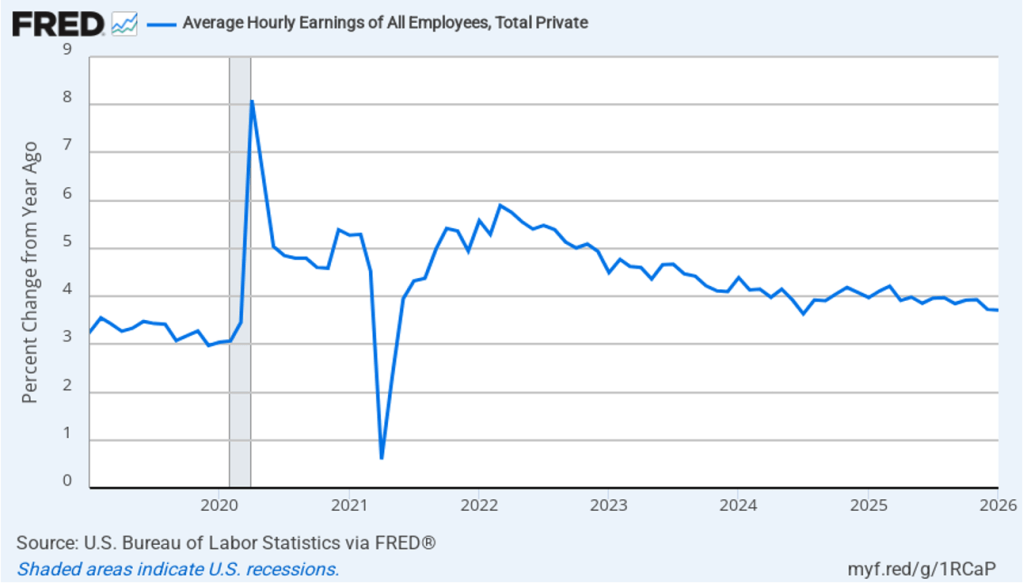

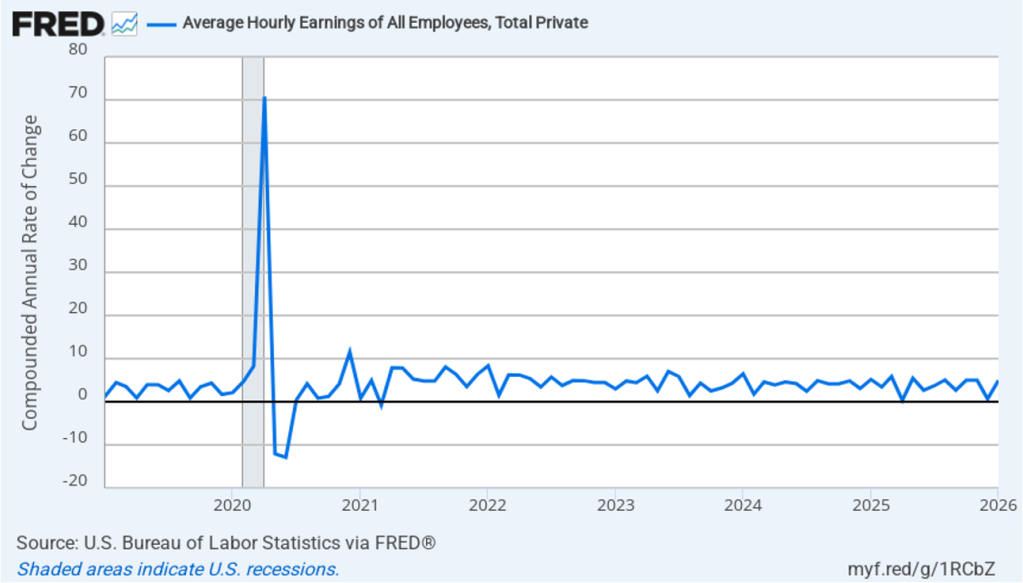

The establishment survey also includes data on average hourly earnings (AHE). As we noted in this post, many economists and policymakers believe the employment cost index (ECI) is a better measure of wage pressures in the economy than is the AHE. The AHE does have the important advantage of being available monthly, whereas the ECI is only available quarterly. The following figure shows the percentage change in the AHE from the same month in the previous year. The AHE increased 3.7 percent in January, the same as in December.

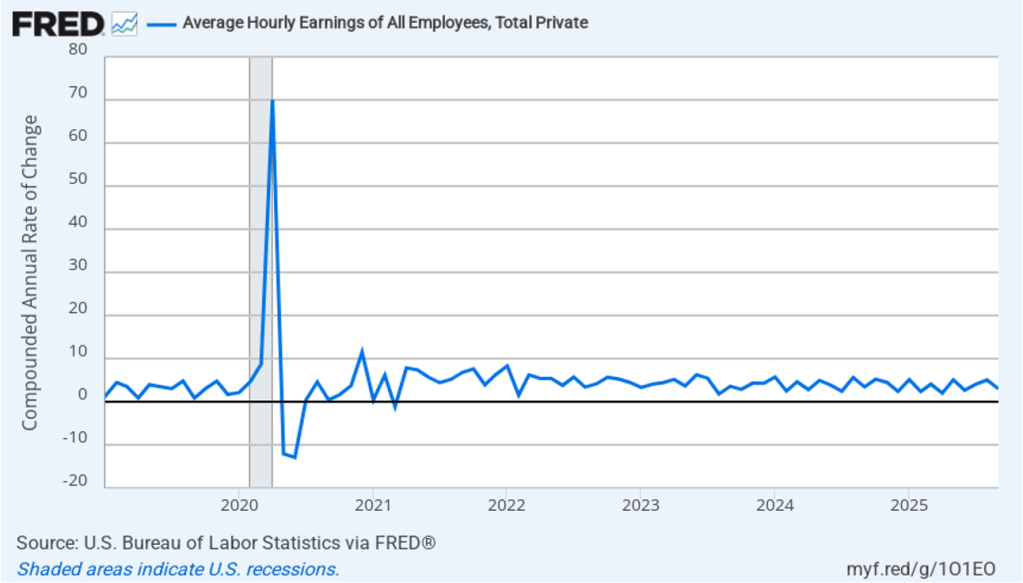

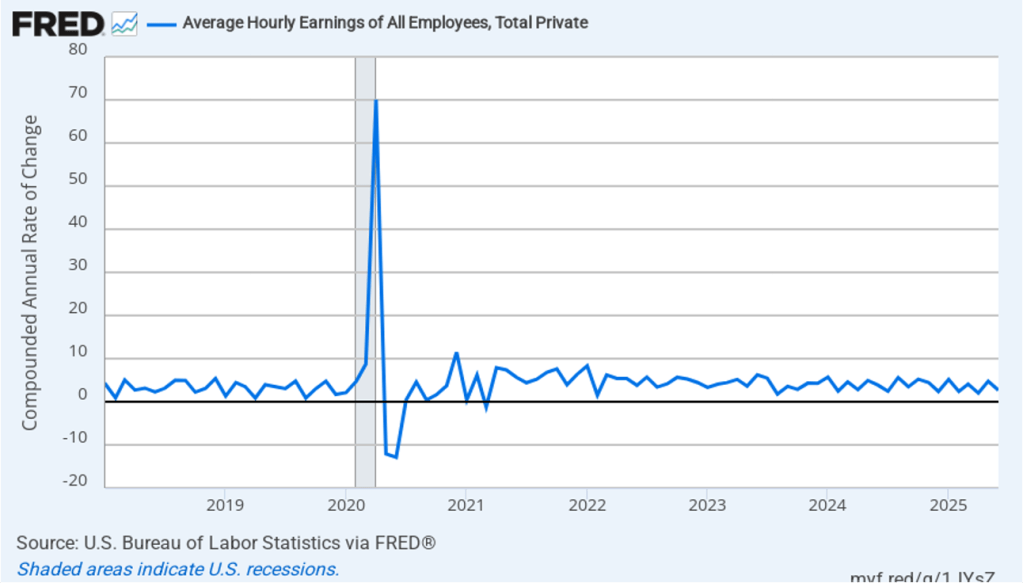

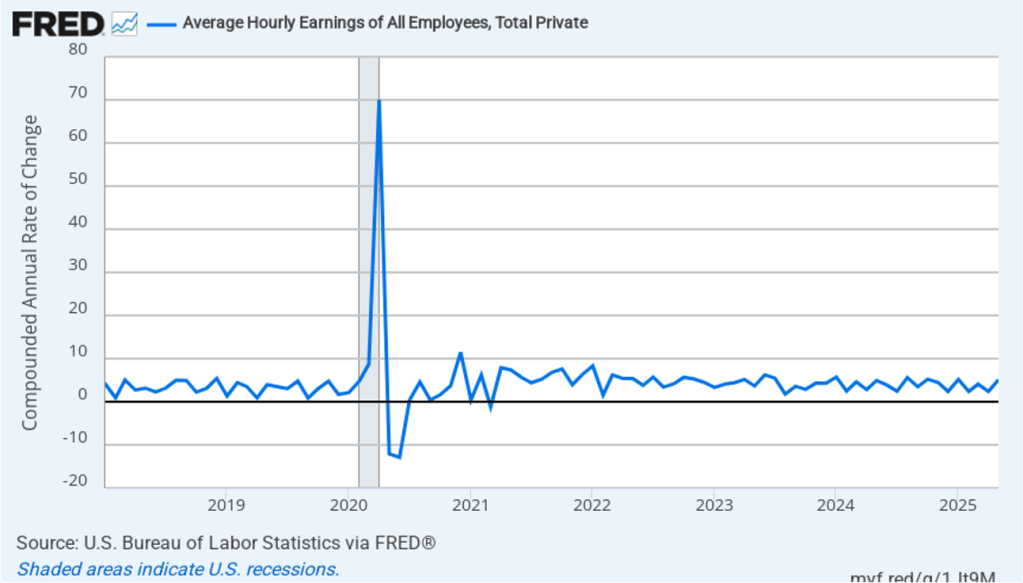

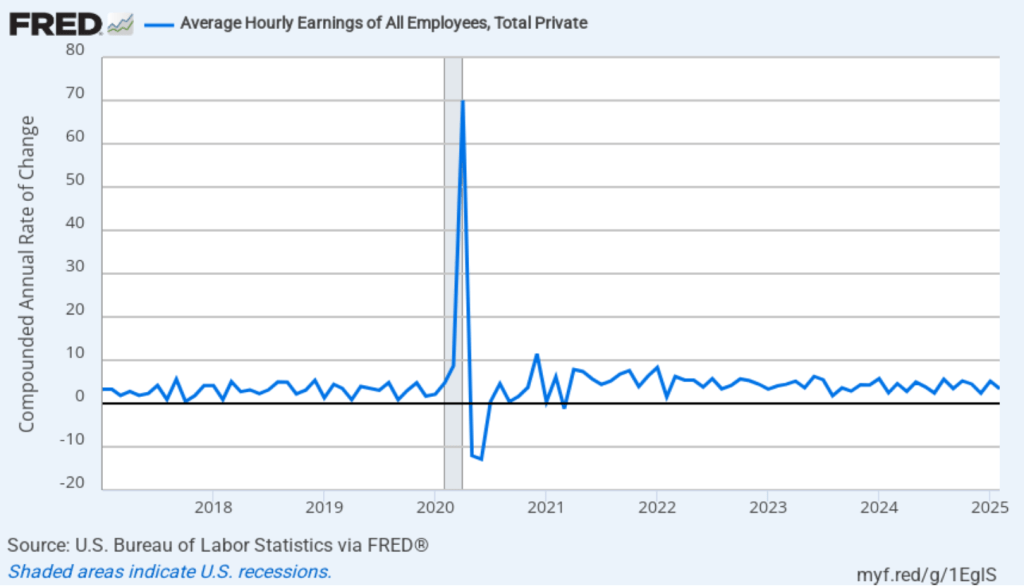

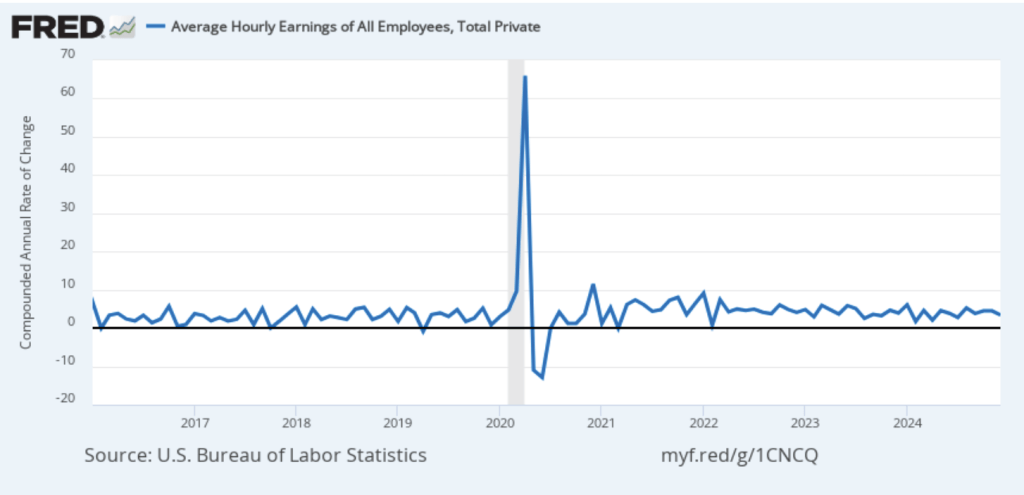

The following figure shows wage inflation calculated by compounding the current month’s rate over an entire year. (The figure above shows what is sometimes called 12-month wage inflation, whereas this figure shows 1-month wage inflation.) One-month wage inflation is much more volatile than 12-month wage inflation—note the very large swings in 1-month wage inflation in April and May 2020 during the business closures caused by the Covid pandemic. In January, the 1-month rate of wage inflation was 5.0 percent, up from 0.7 percent in December. This increase in wage growth may be an indication of a strengthening labor market. But one month’s data from such a volatile series may not accurately reflect longer-run trends in wage inflation.

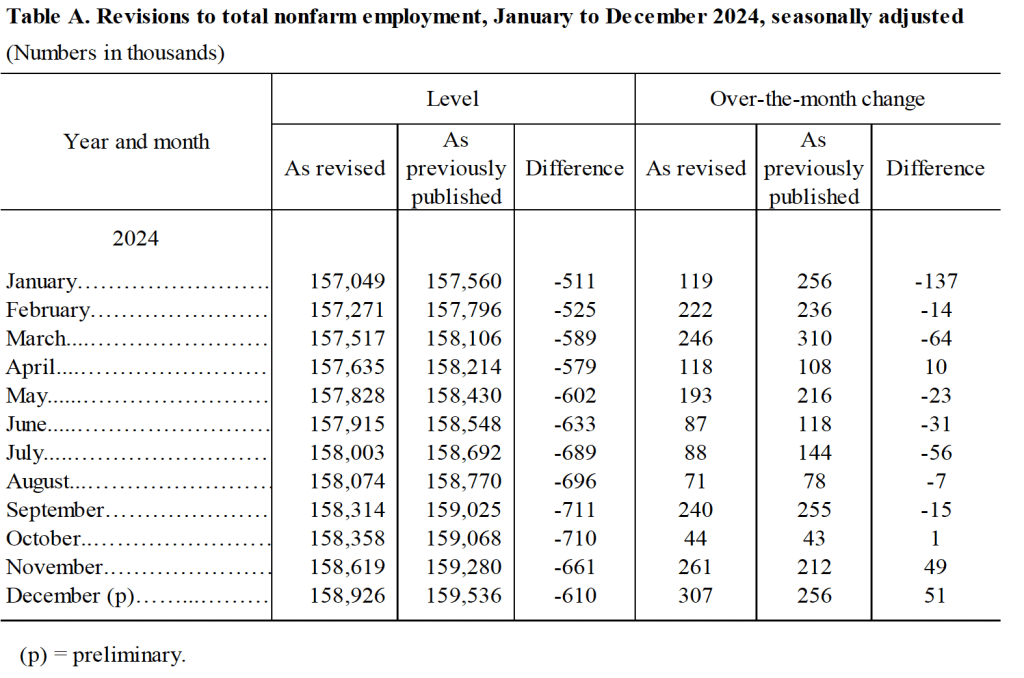

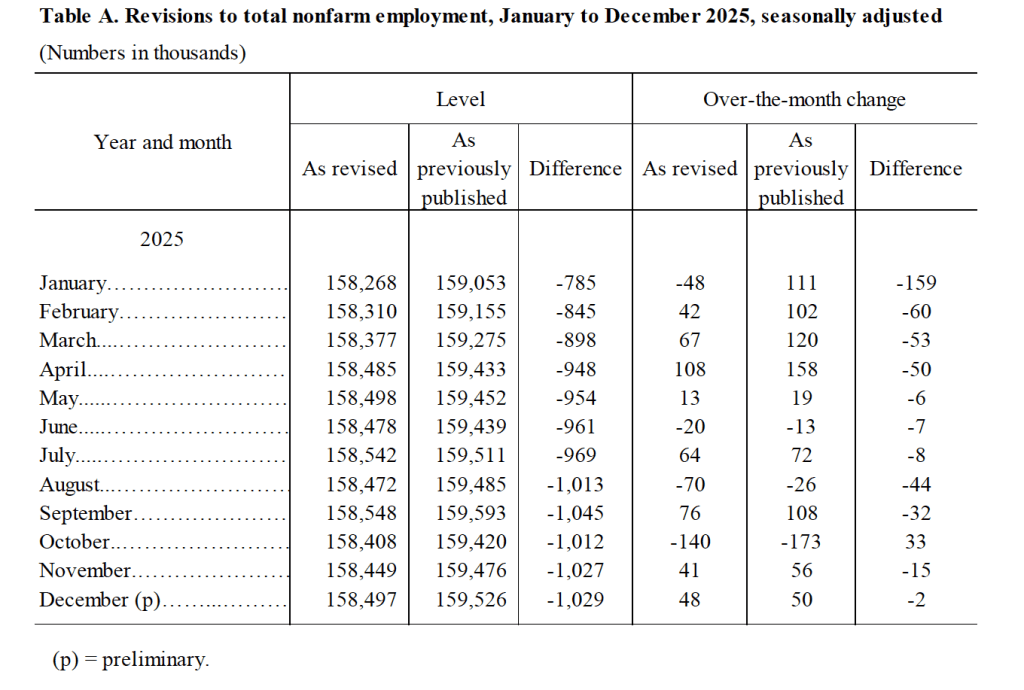

In today’s jobs report, the BLS also included its final annual benchmark revision to the establishment employment data. (We discussed the preliminary annual revision in this blog post last September.) The following table from the jobs report indicates that the revision was quite substantial. The revised estimate of payroll employment is 1,029,000 jobs lower than the original estimate. The increase in total nonfarm employment in 2025 was revised down to only 181,000 from the original estimate of 584,000. Leaving aside the collapse in employment in 2020 during the Covid pandemic, job growth in 2025 was the slowest since 2010 in the immediate aftermath of the Great Recession of 2007–2009.

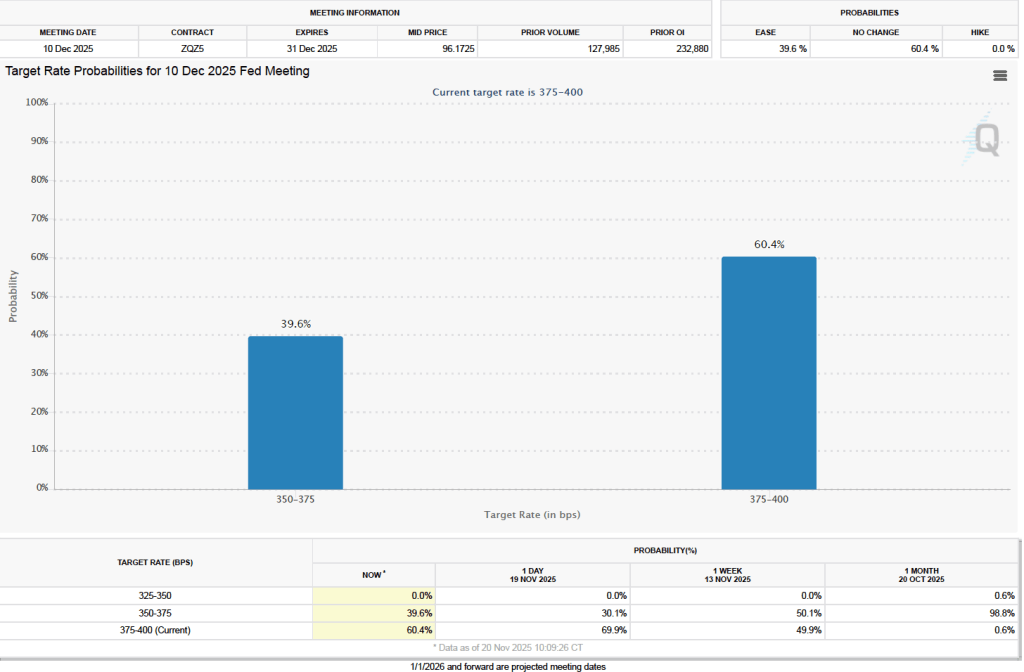

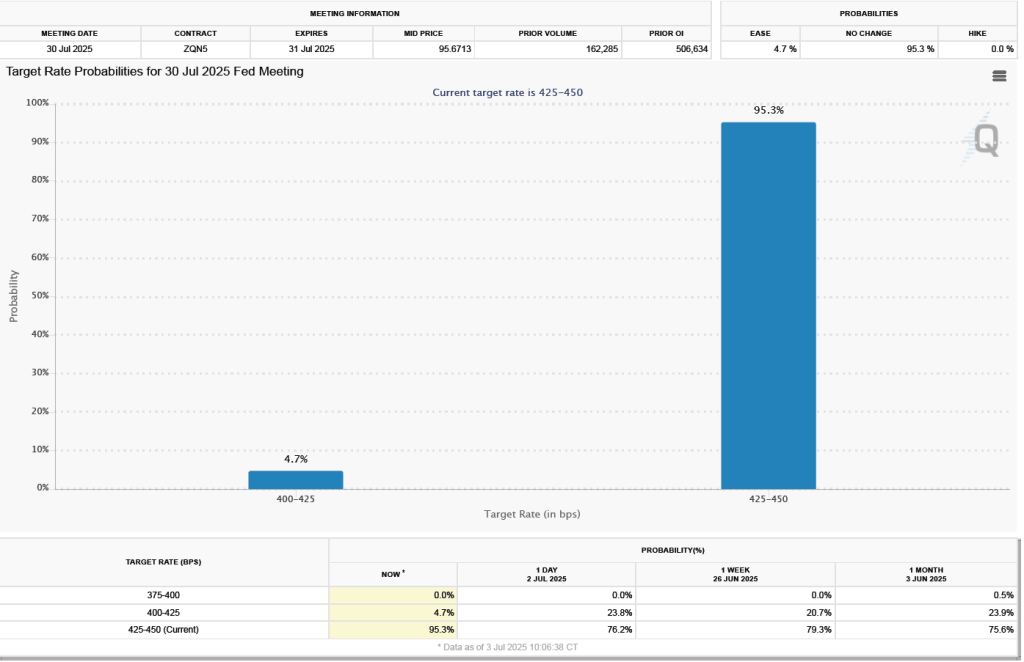

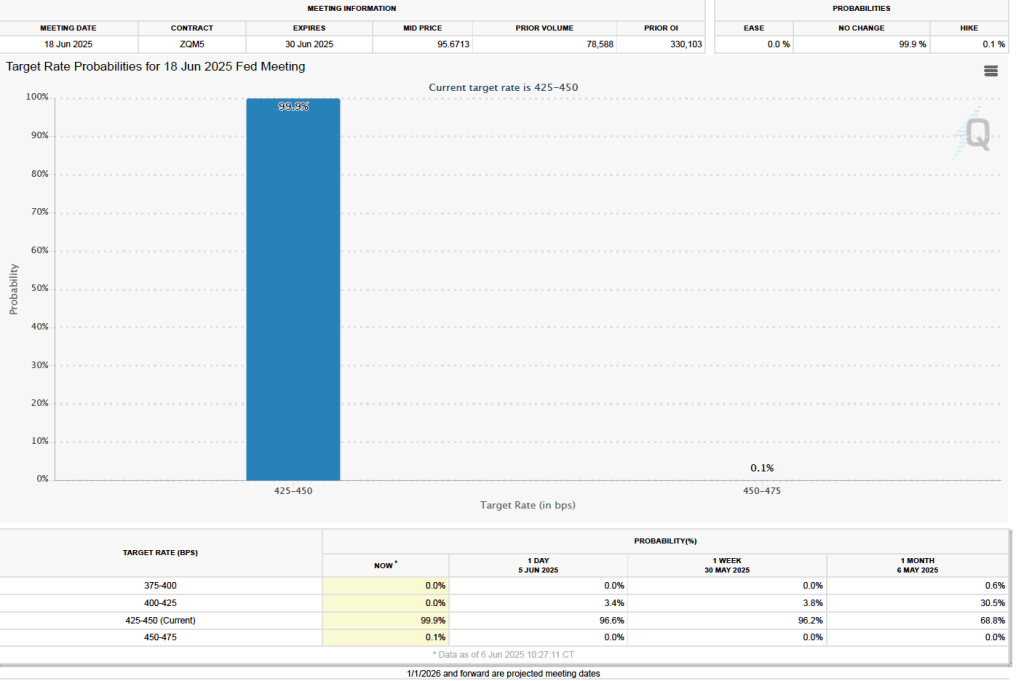

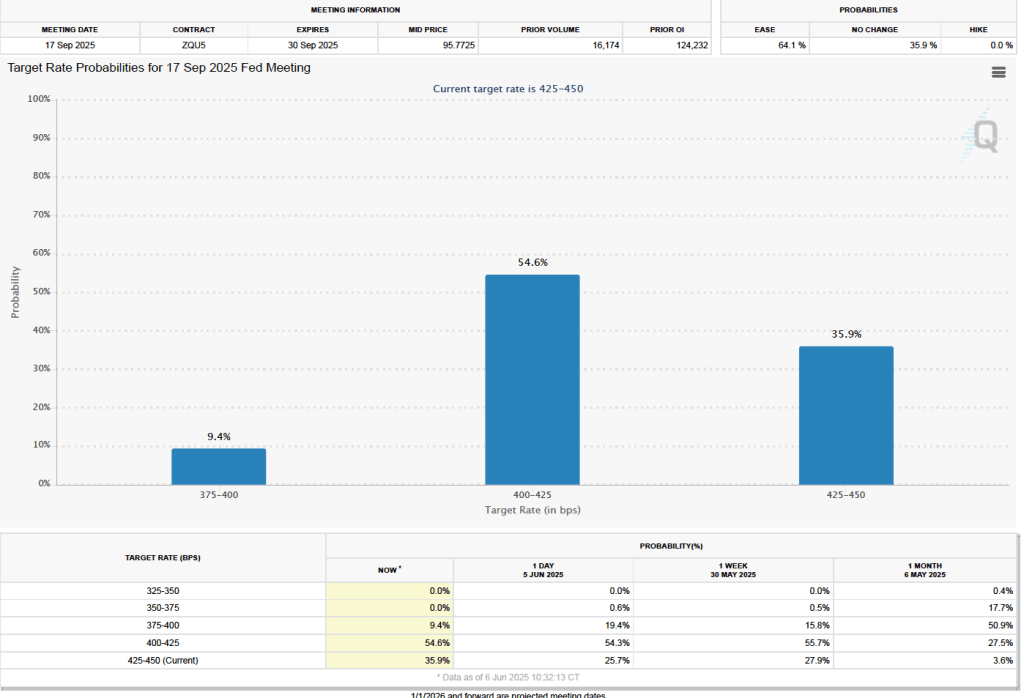

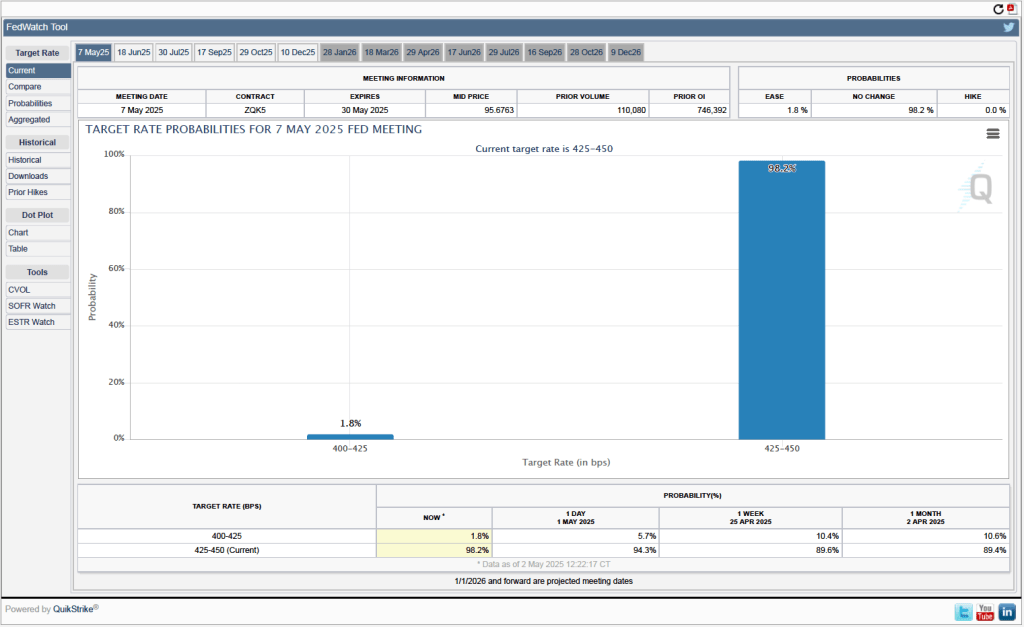

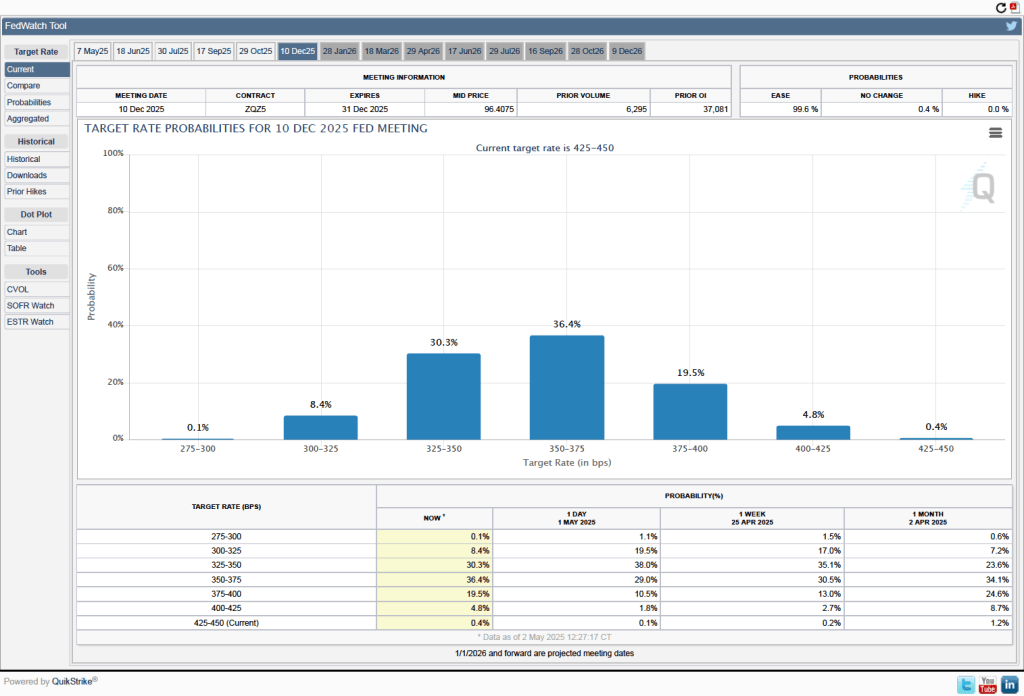

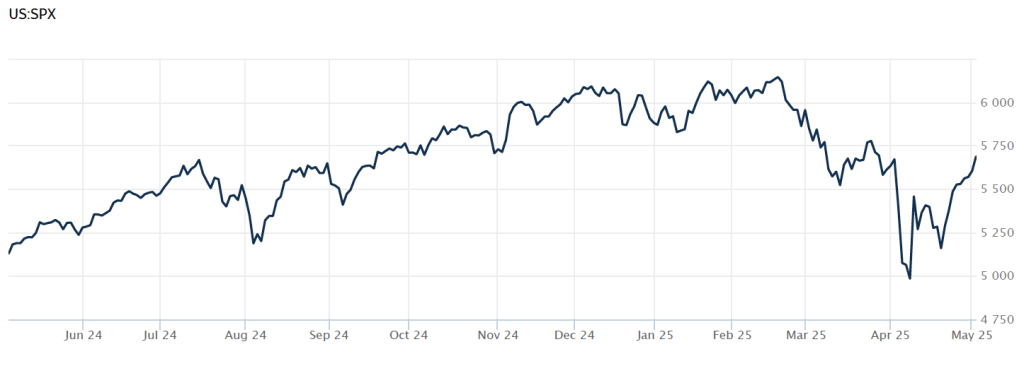

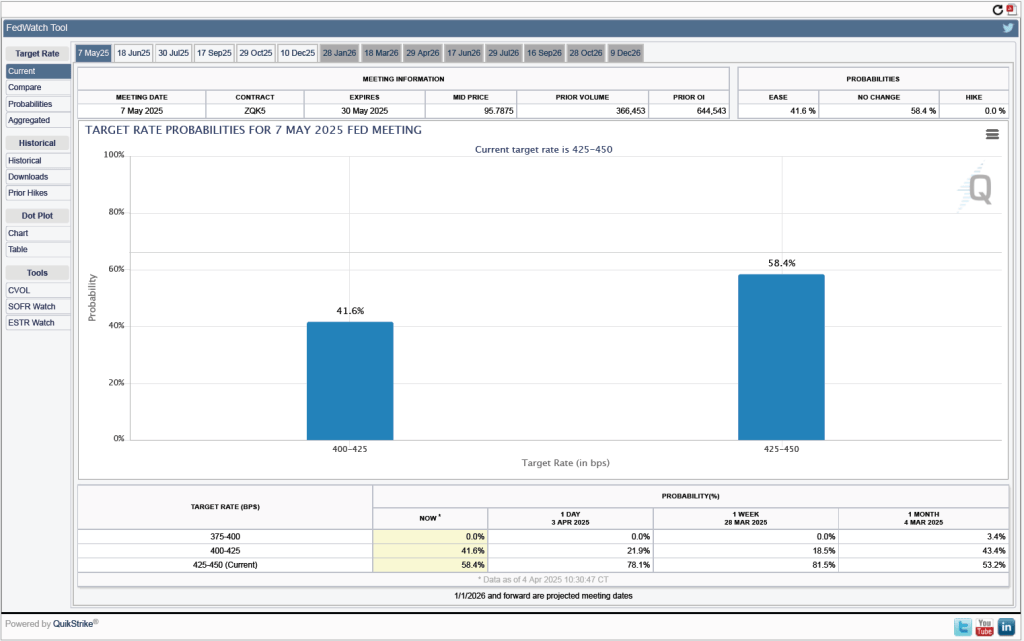

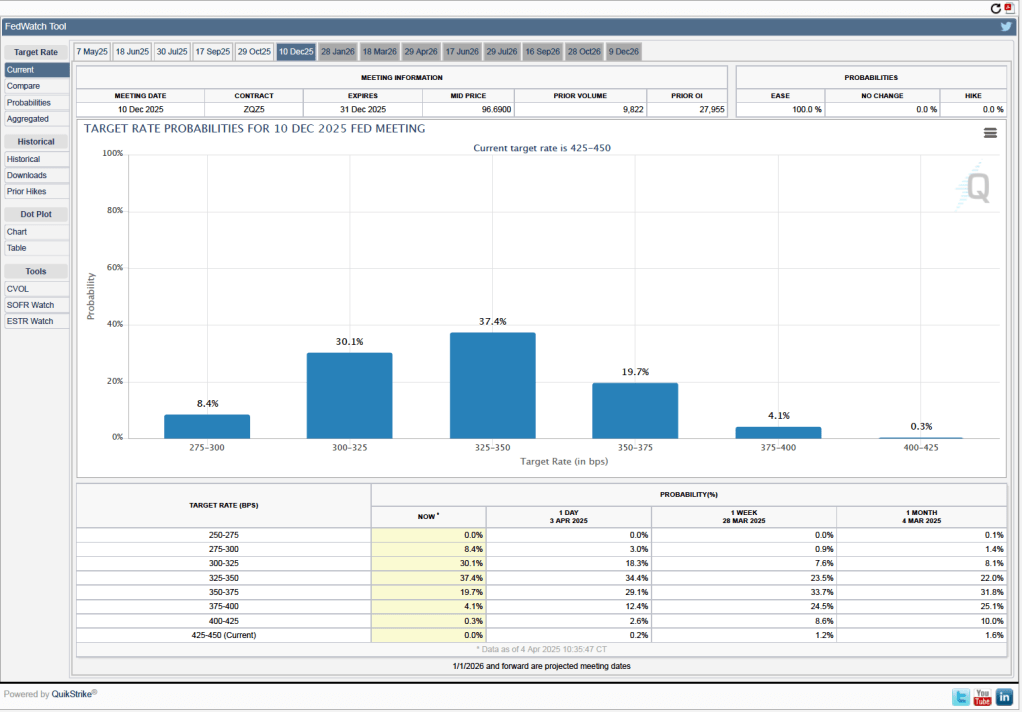

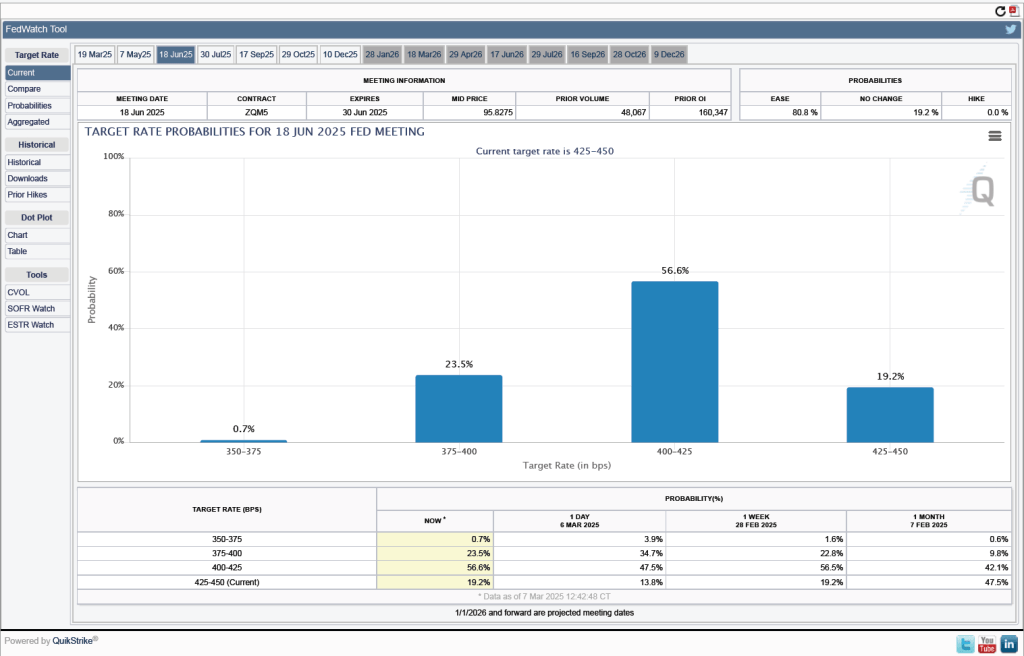

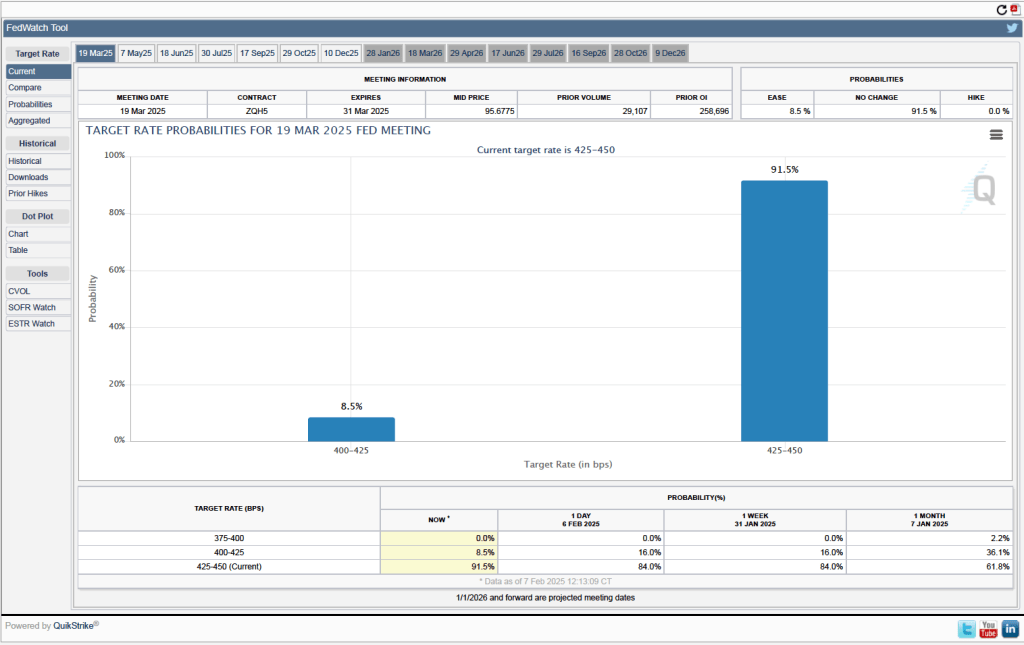

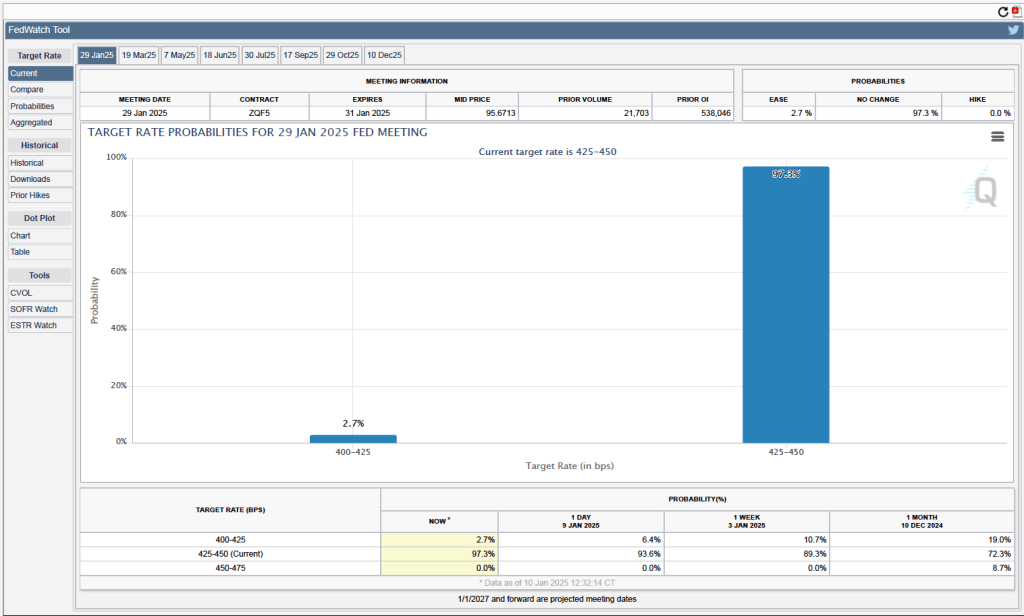

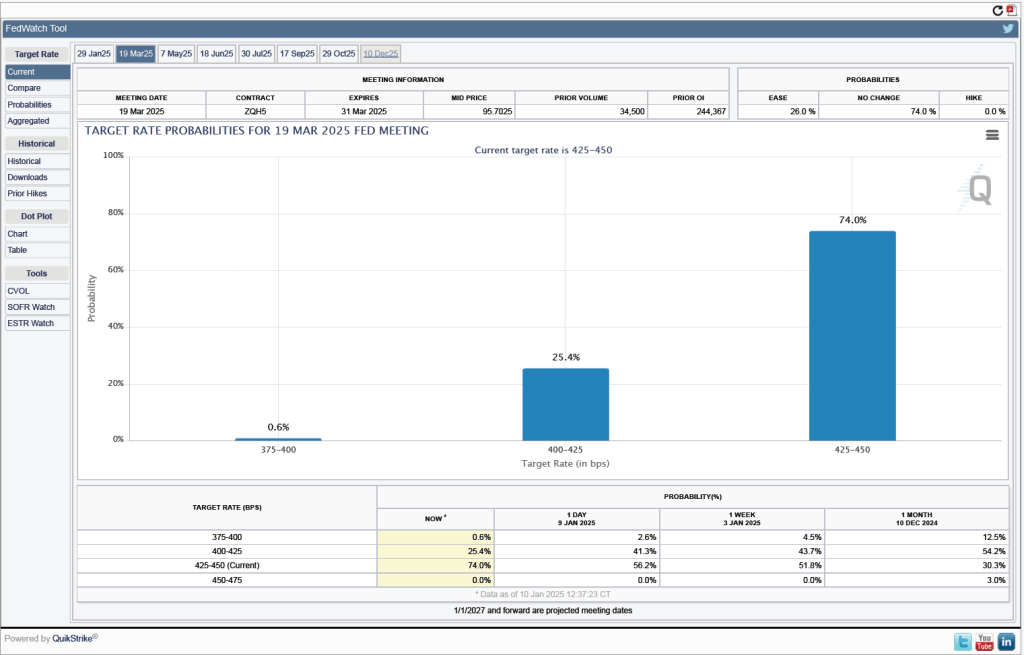

Despite the large downward revision to job growth in 2025, the strong job growth for January in today’s jobs report makes it unlikely that the Federal Reserve’s policymaking Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) will lower its target for the federal funds rate at its next meeting on March 17–18. The probability that investors in the federal funds futures market assign to the FOMC keeping its target rate unchanged at that meeting jumped from 79.9 percent yesterday to 92.1 percent after the release of today’s jobs report.