Four times per year, the members of the Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) publish their projections, or forecasts, of the values of the inflation rate, the unemployment, and changes in real gross domestic product (GDP) for the current year, each of the following two years, and for the “longer run.” The following table, released following the FOMC meeting held on March 15 and 16, 2022, shows the forecasts the members made at that time.

| Median Forecast | Meidan Forecast | Median Forecast | |||

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Longer run | Actual values, March 2022 | |

| Change in real GDP | 2.8% | 2.2% | 2.2% | 1.8% | 3.5% |

| Unemployment rate | 3.5% | 3.5% | 3.6% | 4.0% | 3.6% |

| PCE inflation | 4.3% | 2.7% | 2.3% | 2.0% | 6.6% |

| Core PCE inflation | 4.1% | 2.6% | 2.3% | No forecast | 5.2% |

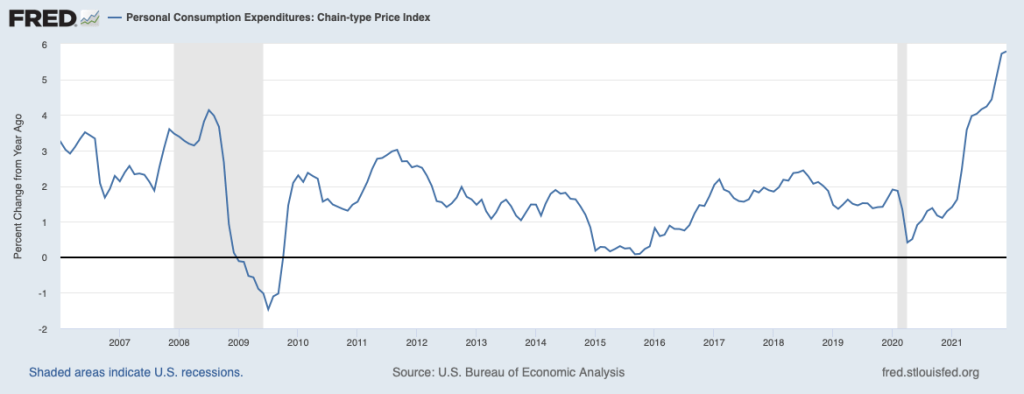

Recall that PCE refers to the consumption expenditures price index, which includes the prices of goods and services that are in the consumption category of GDP. Fed policymakers prefer using the PCE to measure inflation rather than the consumer price index (CPI) because the PCE includes the prices of more goods and services. The Fed uses the PCE to measure whether it is hitting its target inflation rate of 2 percent. The core PCE index leaves out the prices of food and energy products, including gasoline. The prices of food and energy products tend to fluctuate for reasons that do not affect the overall long-run inflation rate. So Fed policymakers believe that core PCE gives a better measure of the underlying inflation rate. (We discuss the PCE and the CPI in the Apply the Concept “Should the Fed Worry about the Prices of Food and Gasoline?” in Macroeconomics, Chapter 15, Section 15.5 (Economics, Chapter 25, Section 25.5)).

The values in the table are the median forecasts of the FOMC members, meaning that the forecasts of half the members were higher and half were lower. The members do not make a longer run forecast for core PCE. The final column shows the actual values of each variable in March 2022. The values in that column represent the percentage in each variable from the corresponding month (or quarter in the case of real GDP) in the previous year. Links to the FOMC’s economic projections can be found on this page of the Federal Reserve’s web site.

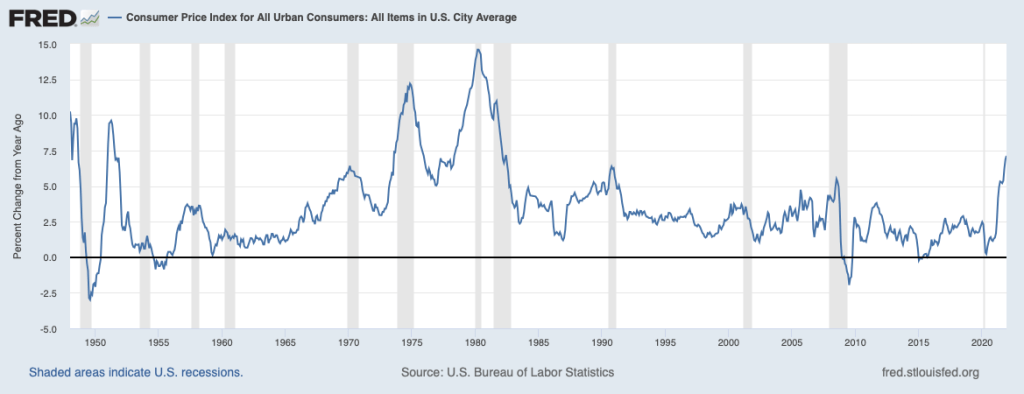

At its March 2022 meeting, the FOMC began increasing its target for the federal funds rate with the expectation that a less expansionary monetary policy would slow the high rates of inflation the U.S. economy was experiencing. Note that in that month, inflation measured by the PCE was running far above the Fed’s target inflation rate of 2 percent.

In raising its target for the federal funds rate and by also allowing its holdings of U.S. Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities to decline, Fed Chair Jerome Powell and the other members of the FOMC were attempting to achieve a soft landing for the economy. A soft landing occurs when the FOMC is able to reduce the inflation rate without causing the economy to experience a recession. The forecast values in the table are consistent with a soft landing because they show inflation declining towards the Fed’s target rate of 2 percent while the unemployment rate remains below 4 percent—historically, a very low unemployment rate—and the growth rate of real GDP remains positive. By forecasting that real GDP would continue growing while the unemployment rate would remain below 4 percent, the FOMC was forecasting that no recession would occur.

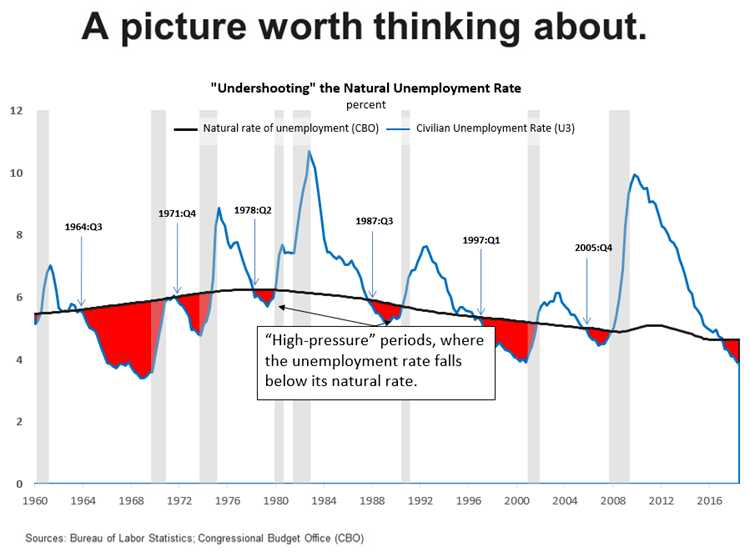

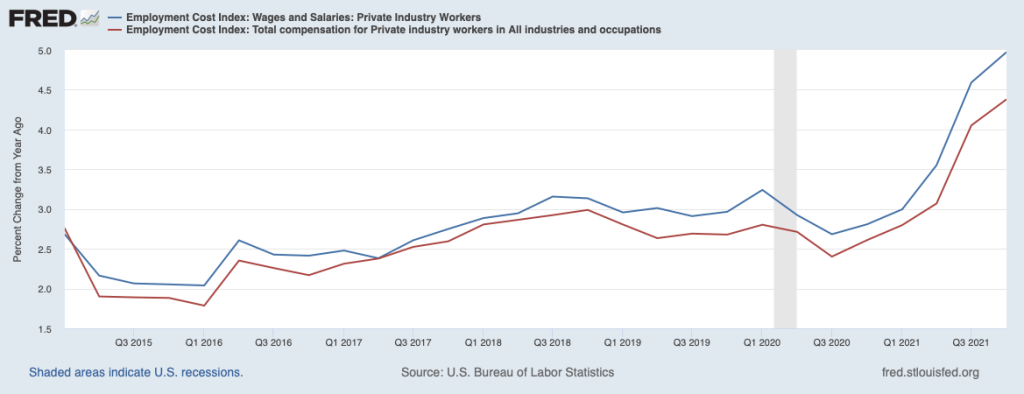

Some economists see an inconsistency in the FOMC’s forecasts of unemployment and inflation as shown in the table. They argued that to bring down the inflation rate as rapidly as the forecasts indicated, the FOMC would have to cause a significant decline in aggregate demand. But if aggregate demand declined significantly, real GDP would either decline or grow very slowly, resulting in the unemployment rising above 4 percent, possibly well above that rate. For instance, writing in the Economist magazine, Jón Steinsson of the University of California, Berkeley, noted that the FOMC’s “combination of forecasts [of inflation and unemployment] has been dubbed the ‘immaculate disinflation’ because inflation is seen as falling rapidly despite a very tight labor market and a [federal funds] rate that is for the most part negative in real terms (i.e., adjusted for inflation).”

Similarly, writing in the Washington Post, Harvard economist and former Treasury secretary Lawrence Summers noted that “over the past 75 years, every time inflation has exceeded 4 percent and unemployment has been below 5 percent, the U.S. economy has gone into recession within two years.”

In an interview in the Financial Times, Olivier Blanchard, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics and former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund, agreed. In their forecasts, the FOMC “had unemployment staying at 3.5 percent throughout the next two years, and they also had inflation coming down nicely to two point something. That just will not happen. …. [E]ither we’ll have a lot more inflation if unemployment remains at 3.5 per cent, or we will have higher unemployment for a while if we are actually to inflation down to two point something.”

While all three of these economists believed that unemployment would have to increase if inflation was to be brought down close to the Fed’s 2 percent target, none were certain that a recession would occur.

What might explain the apparent inconsistency in the FOMC’s forecasts of inflation and unemployment? Here are three possibilities:

- Fed policymakers are relatively optimistic that the factors causing the surge in inflation—including the economic dislocations due to the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the surge in federal spending in early 2021—are likely to resolve themselves without the unemployment rate having to increase significantly. As Steinsson puts it in discussing this possibility (which he believes to be unlikely) “it is entirely possible that inflation will simply return to target as the disturbances associated with Covid-19 and the war in Ukraine dissipate.”

- Fed Chair Powell and other members of the FOMC were convinced that business managers, workers, and investors still expected that the inflation rate would return to 2 percent in the long run. As a result, none of these groups were taking actions that might lead to a wage-price spiral. (We discussed the possibility of a wage-price spiral in earlier blog post.) For instance, at a press conference following the FOMC meeting held on May 3 and 4, 2022, Powell argued that, “And, in fact, inflation expectations [at longer time horizons] come down fairly sharply. Longer-term inflation expectations have been reasonably stable but have moved up to—but only to levels where they were in 2014, by some measures.” If Powell’s assessment was correct that expectations of future inflation remained at about 2 percent, the probability of a soft landing was increased.

- We should mention the possibility that at least some members of the FOMC may have expected that the unemployment rate would increase above 4 percent—possibly well above 4 percent—and that the U.S. economy was likely to enter a recession during the coming months. They may, however, have been unwilling to include this expectation in their published forecasts. If members of the FOMC state that a recession is likely, businesses and households may reduce their spending, which by itself could cause a recession to begin.

Sources: Martin Wolf, “Olivier Blanchard: There’s a for Markets to Focus on the Present and Extrapolate It Forever,” ft.com, May 26, 2022; Lawrence Summers, “My Inflation Warnings Have Spurred Questions. Here Are My Answers,” Washington Post, April 5, 2022; Jón Steinsson, “Jón Steinsson Believes That a Painless Disinflation Is No Longer Plausible,” economist.com, May 13, 2022; Federal Open Market Committee, “Summary of Economic Projections,” federalreserve.gov, March 16, 2022; and Federal Open Market Committee, “Transcript of Chair Powell’s Press Conference May 4, 2022,” federalreserve.gov, May 4, 2022.