Photo courtesy of Lena Buonanno.

Yesterday, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) released quarterly data on the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index as part of its advance estimate of third quarter GDP. (We discuss that release in this blog post.) Today, the BEA released monthly data on the PCE as part of its Personal Income and Outlays report. In addition, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released quarterly data on the Employment Cost Index (ECI).

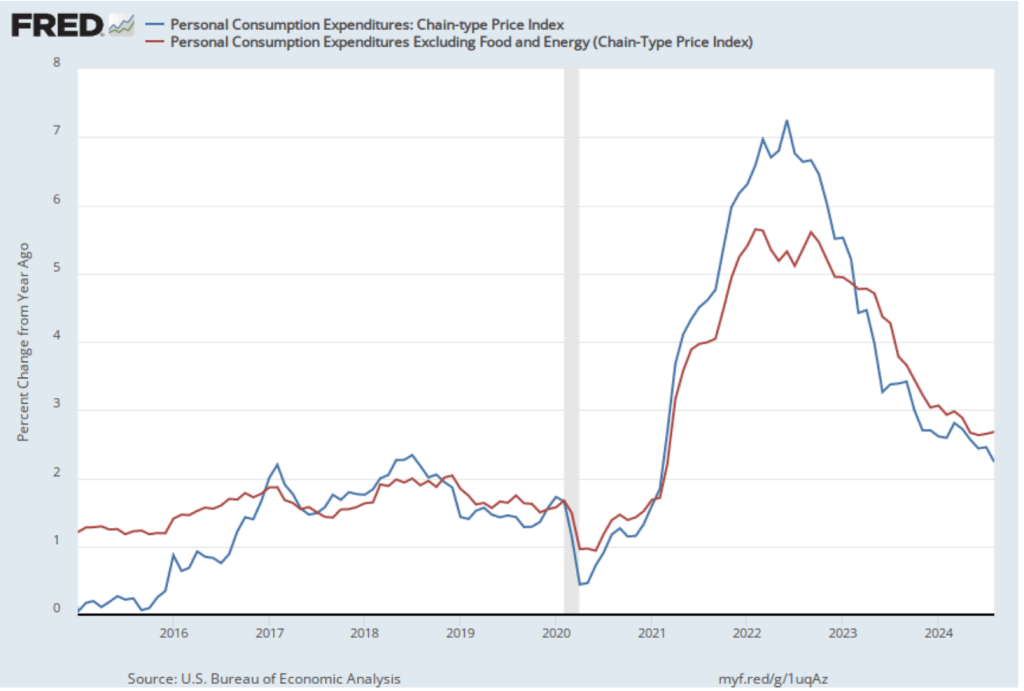

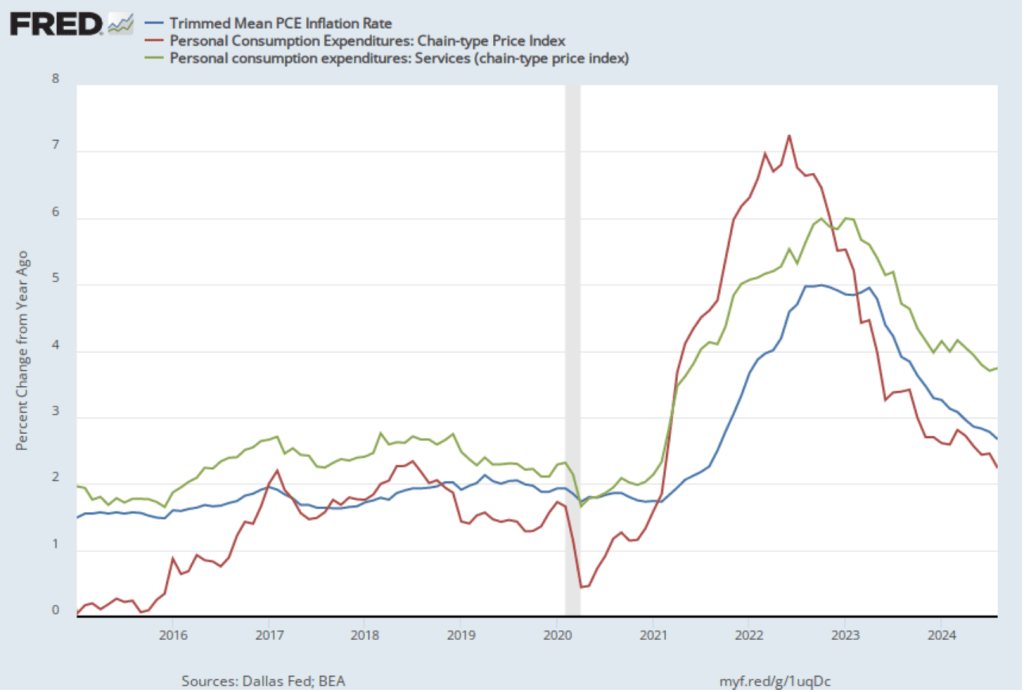

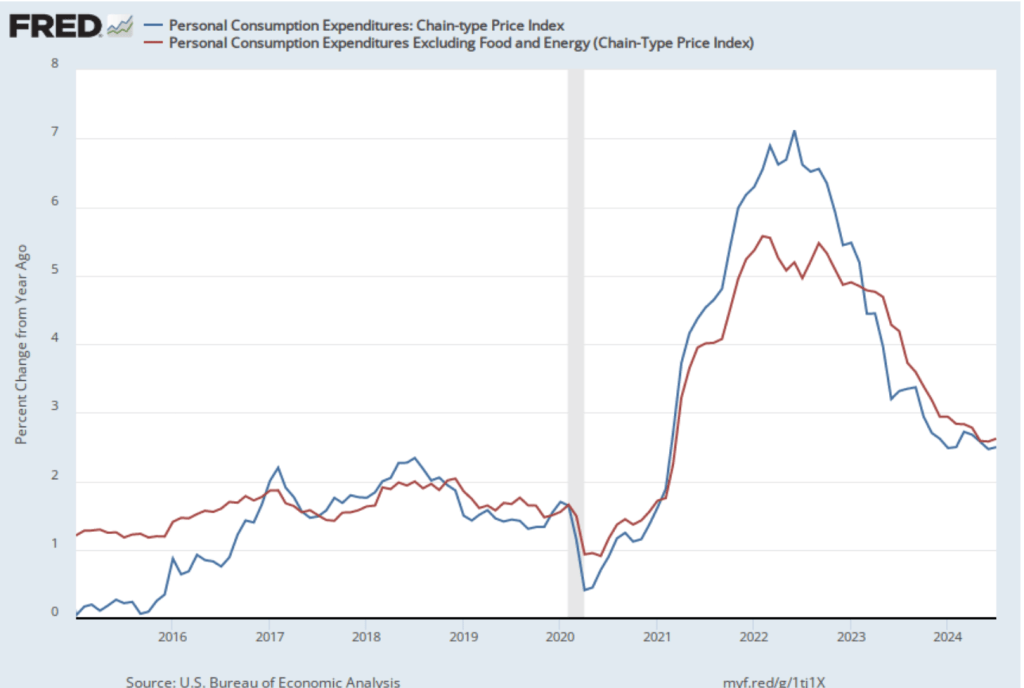

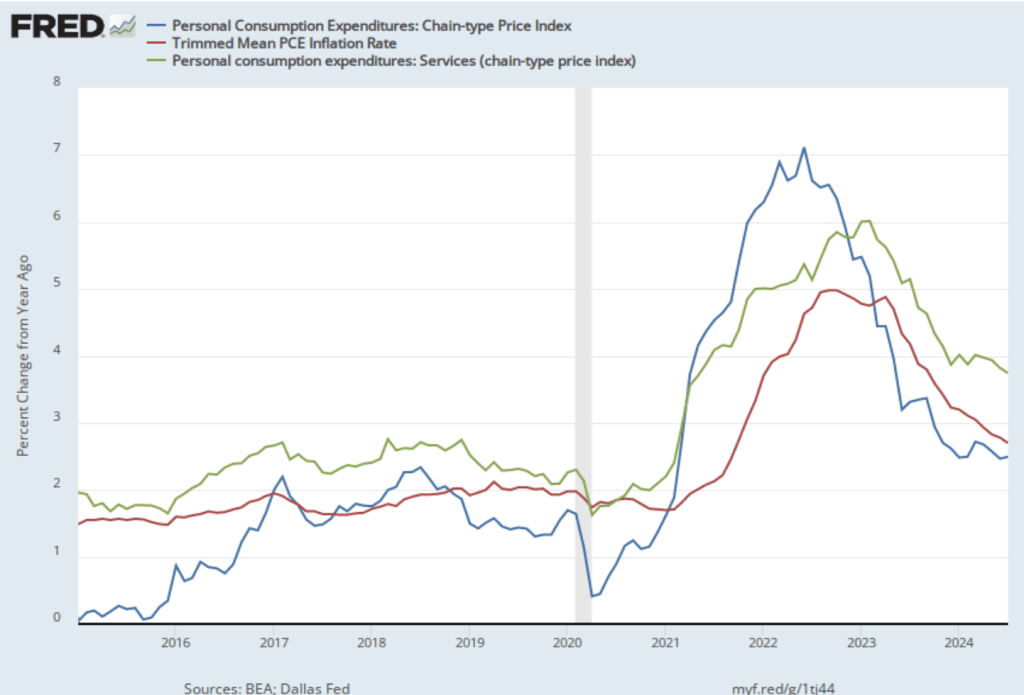

The Fed relies on annual changes in the PCE price index to evaluate whether it’s meeting its 2 percent annual inflation target. The following figure shows PCE inflation (blue line) and core PCE inflation (red line)—which excludes energy and food prices—for the period since January 2016 with inflation measured as the percentage change in the PCE from the same month in the previous year. Measured this way, in September PCE inflation (the blue line) was 2.1 percent, down from 2.3 percent in August. Core PCE inflation (the red line) in September was 2.7 percent, which was unchanged from August. PCE inflation was in accordance with the expectations of economists surveyed by the Wall Street Journal, but core inflation was higher than expected.

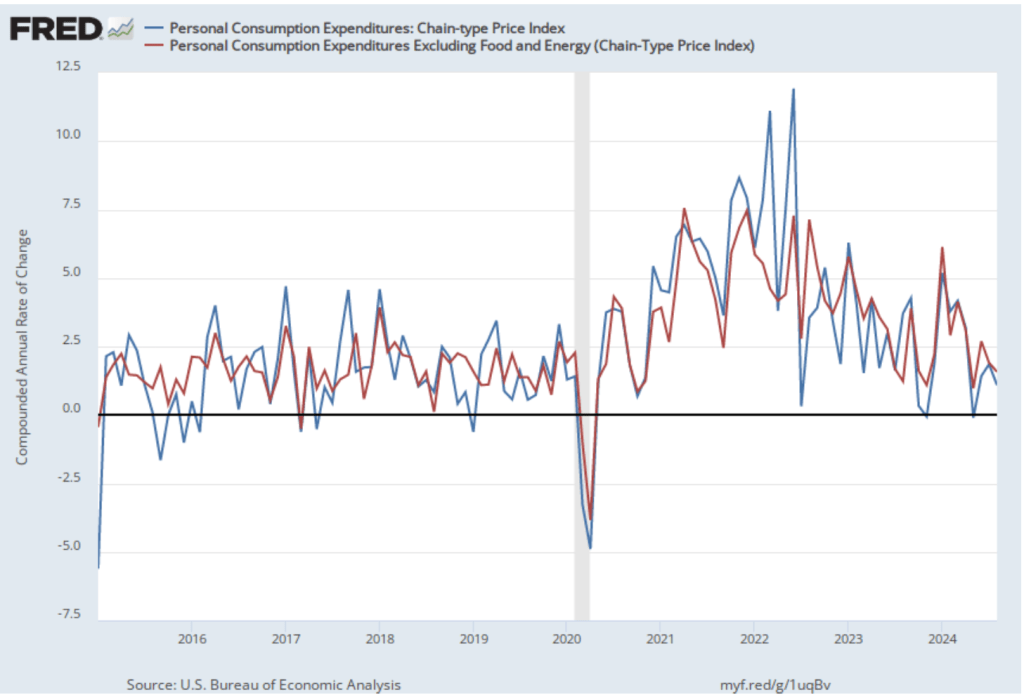

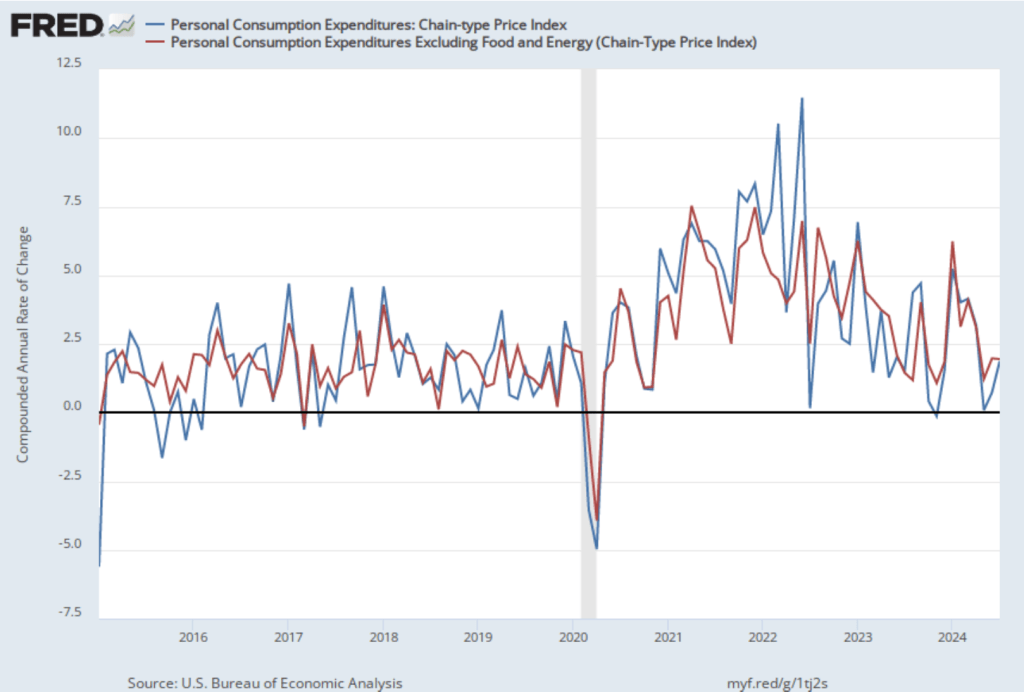

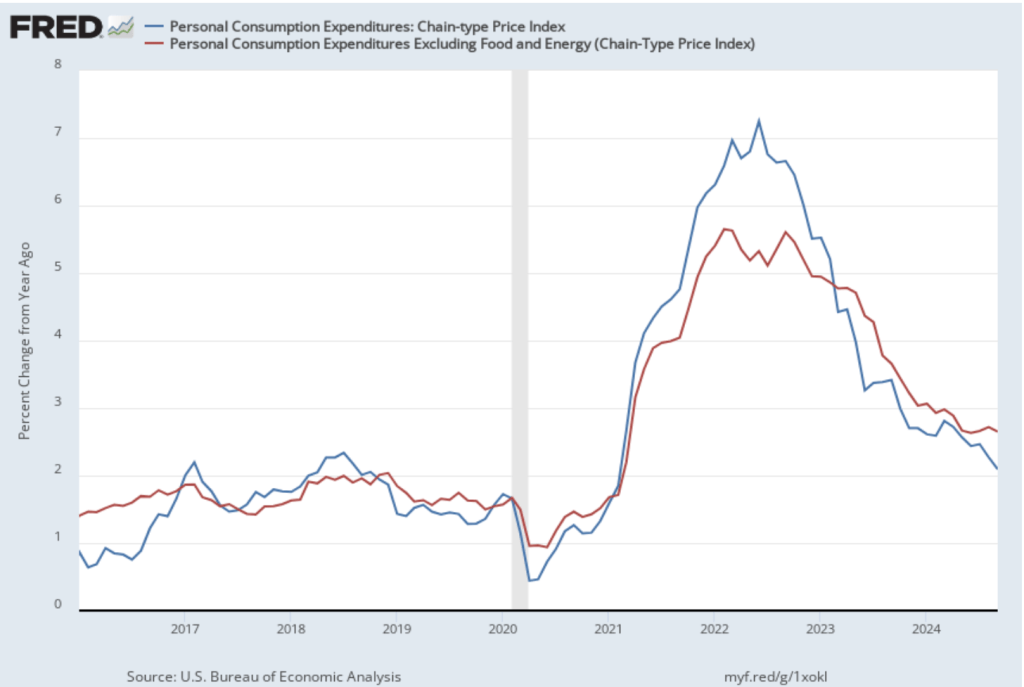

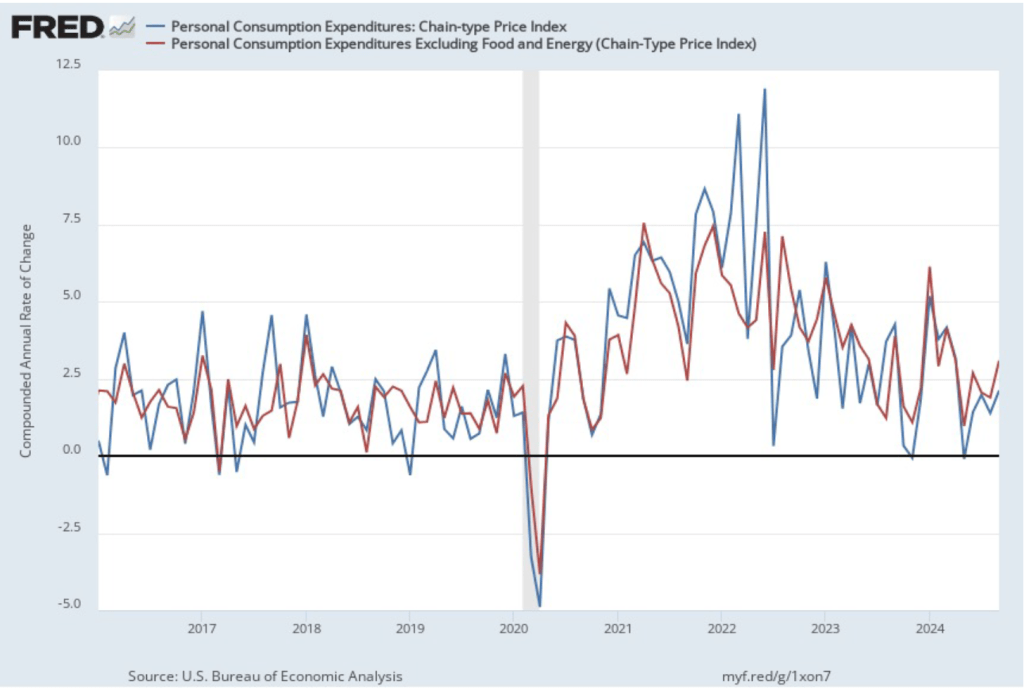

The following figure shows PCE inflation and core PCE inflation calculated by compounding the current month’s rate over an entire year. (The figure above shows what is sometimes called 12-month inflation, while this figure shows 1-month inflation.) Measured this way, PCE inflation rose in September to 2.1 percent from 1.4 percent in August. Core PCE inflation rose from 1.9 percent in August to 3.1 percent in June. Because core inflation is generally a better measure of the underlying trend in inflation, both 12-month and 1-month core PCE inflation indicate that inflation may still run above the Fed’s 2 percent target in coming months. But the usual caution applies that data from one month shouldn’t be overly relied on.

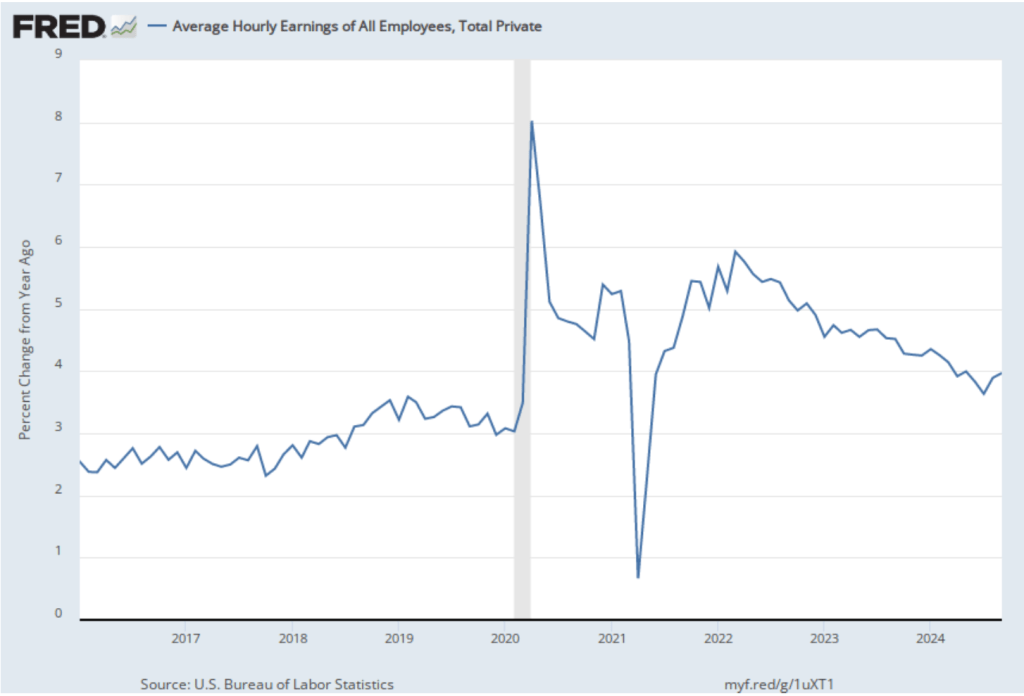

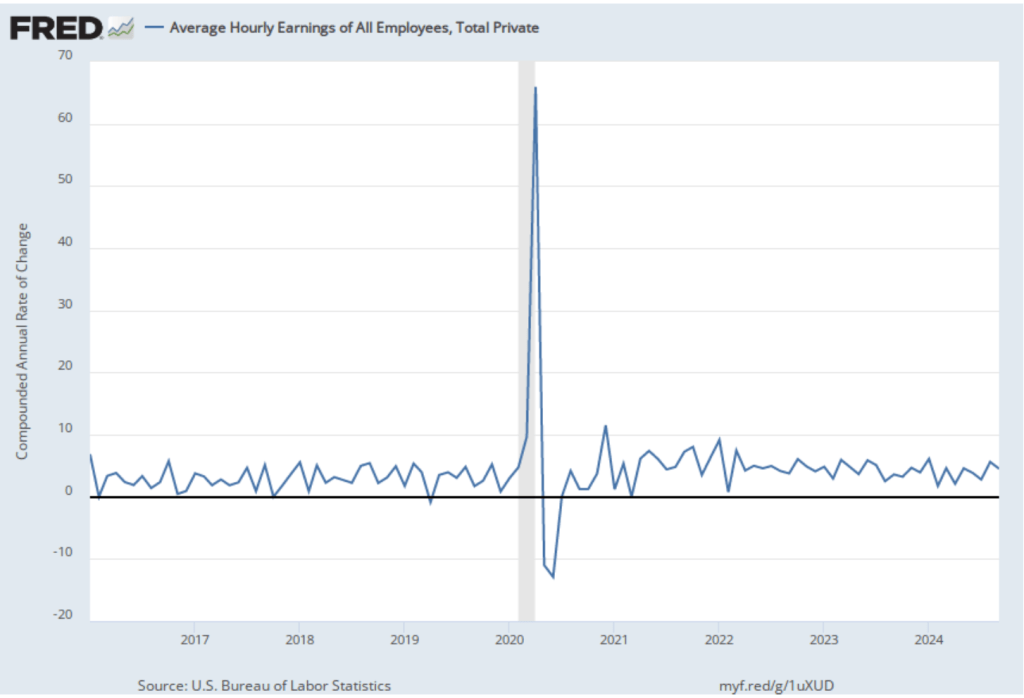

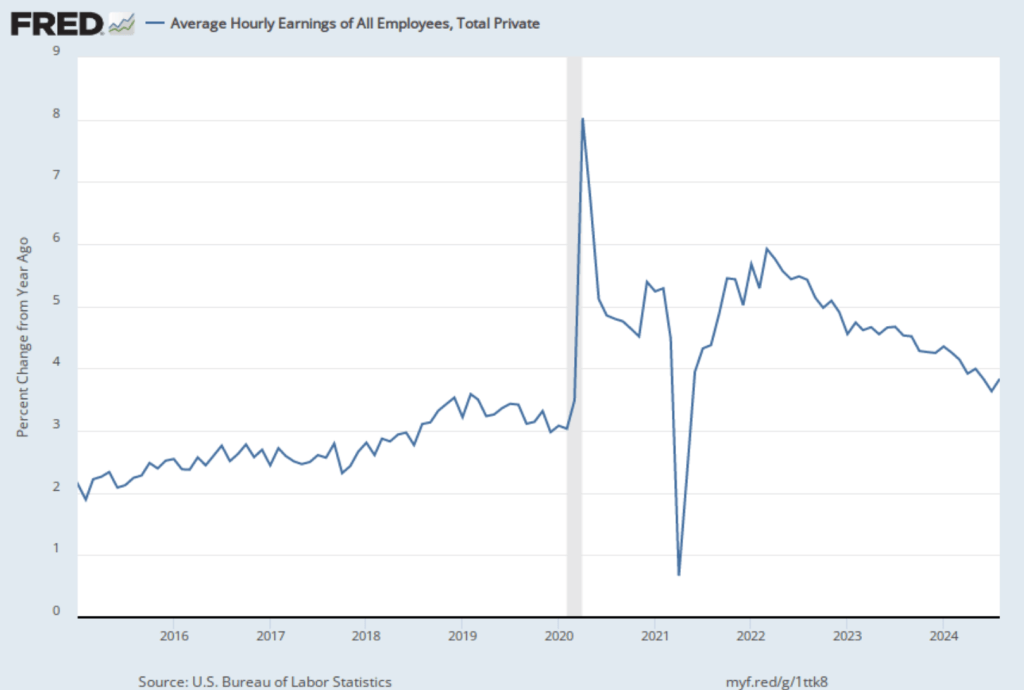

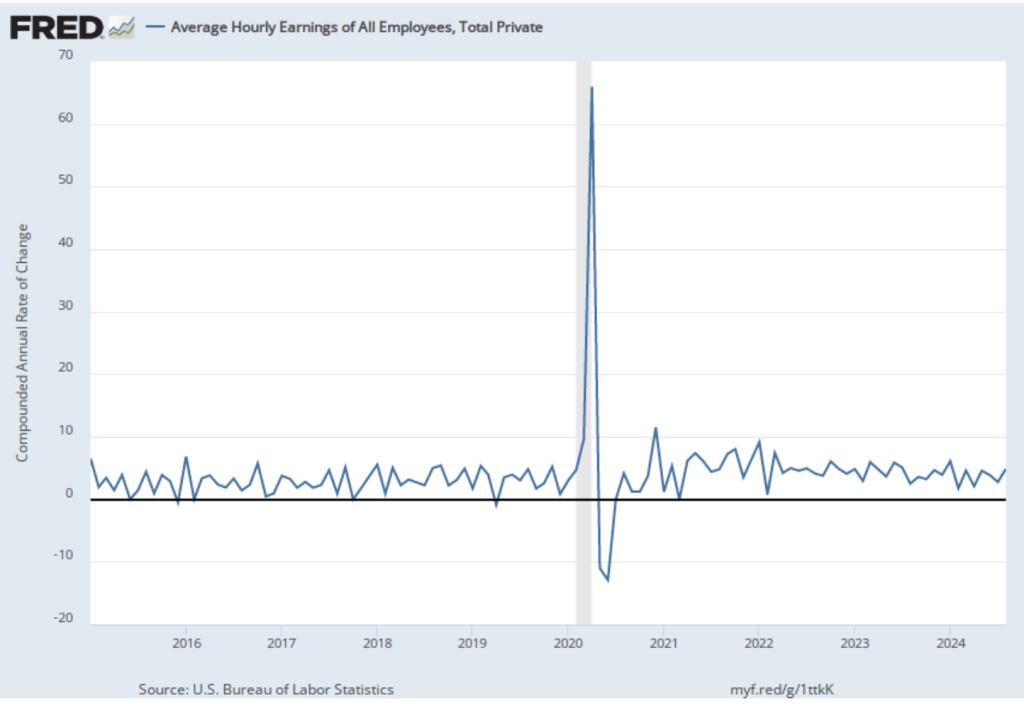

Turning to wages, as we’ve noted in earlier posts, as a measure of the rate of increase in labor costs, the Fed’s policy-making Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) prefers the ECI to average hourly earnings (AHE).

The AHE is calculated by adding all of the wages and salaries workers are paid—including overtime and bonus pay—and dividing by the total number of hours worked. As a measure of how wages are increasing or decreasing during a particular period, AHE can suffer from composition effects because AHE data aren’t adjusted for changes in the mix of occupations workers are employed in. For example, during a period in which there is a decline in the number of people working in occupations with higher-than-average wages, perhaps because of a downturn in some technology industries, AHE may show wages falling even though the wages of workers who are still employed have risen. In contrast, the ECI holds constant the mix of occupations in which people are employed. The ECI does have this drawback: It is only available quarterly whereas the AHE is available monthly.

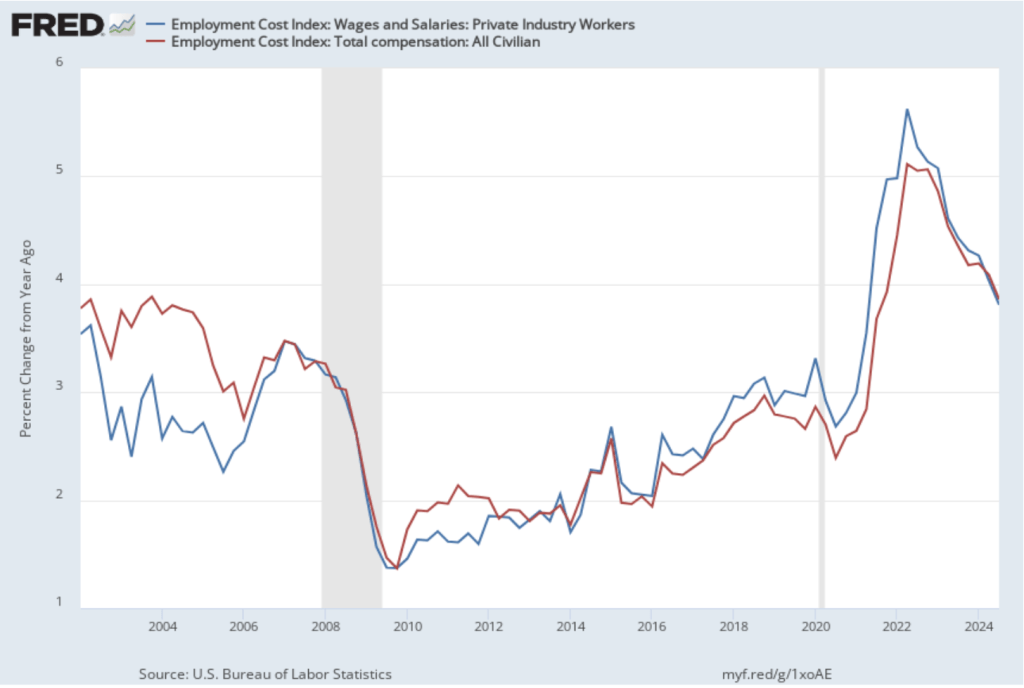

The data released this morning indicate that labor costs continue to increase at a rate that is higher than the rate that is likely needed for the Fed to hit its 2 percent price inflation target. The following figure shows the percentage change in the employment cost index for all civilian workers from the same quarter in 2023. The blue line shows only wages and salaries while the red line shows total compensation, including non-wage benefits like employer contributions to health insurance. The rate of increase in the wage and salary measure decreased from 4.0 percent in the second quarter of 2024 to 3.8 percent in the third quarter. The movement in the rate of increase in compensation was very similar, decreasing from 4.1 percent in the second quarter of 2024 to 3.9 percent in the third quarter.

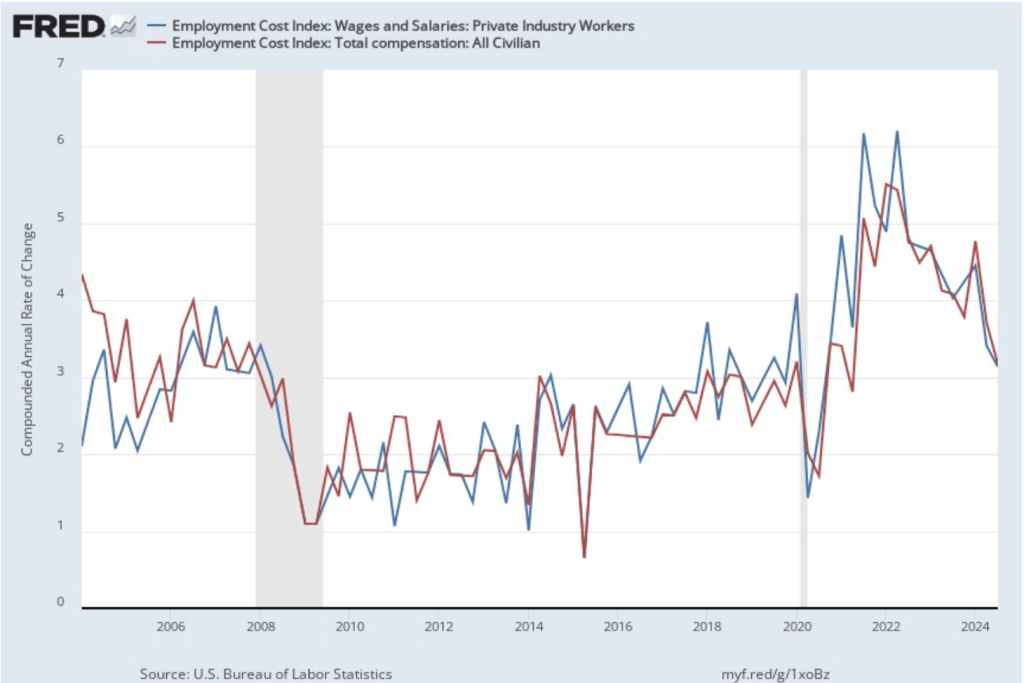

If we look at the compound annual growth rate of the ECI—the annual rate of increase assuming that the rate of growth in the quarter continued for an entire year—we find that the rate of increase in wages and salaries decreased from 3.4 percent in the second quarter of 2024 to 3.1 percent in the third quarter. Similarly, the rate of increase in compensation decreased from 3.7 percent in the second quarter of 2024 to 3.2 percent in the third quarter. So, this measure indicates that there has been some easing of wage inflation in the third quarter, although, again, we have to use caution in interpreting one quarter’s data.

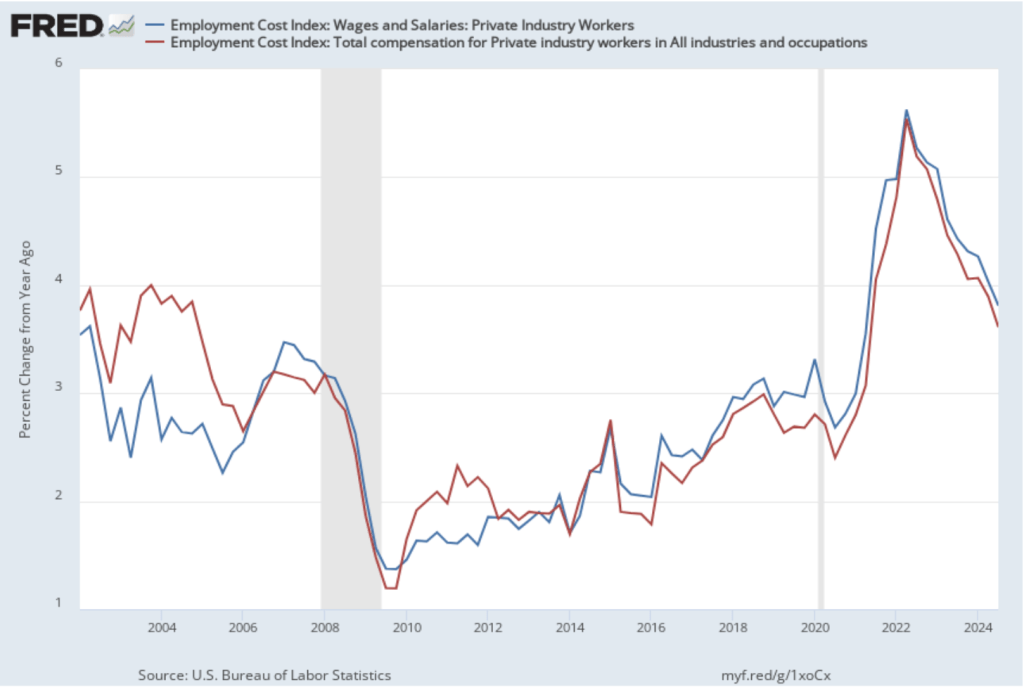

Some economists and policymakers prefer to look at the rate of increase in ECI for private industry workers rather than for all civilian workers because the wages of government workers are less likely to respond to inflationary pressure in the labor market. The first of the following figures shows the rate of increase of wages and salaries and in total compensation for private industry workers measured as the percentage increase from the same quarter in the previous year. The second figure shows the rate of increase calculated as a compound growth rate.

Both figures show results consistent with the 12-month PCE inflation figures: A decrease in wage inflation during the third quarter compared with the second quarter but with wage inflation still running somewhat above the level consistent with the Fed’s 2 percent price inflation target.

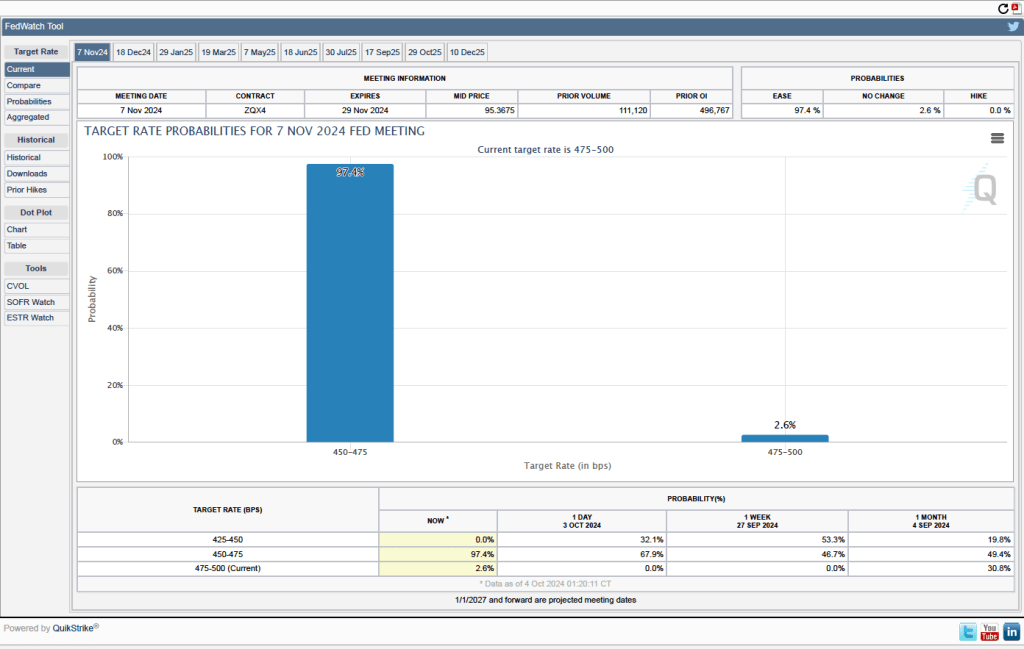

Taken together, the PCE and ECI data released today indicate that the Fed has not yet managed to bring about soft landing—returning inflation to its 2 percent target without pushing the economy into a recession. As we noted in yesterday’s post, although output growth remains strong, there are some indications that the labor market may be weakening. If so, future months may see a further decrease in wage growth that will make it more likely that the Fed will hit its inflation target. The BLS is scheduled to release its “Employment Situation” report for October on Friday, November 1. That report will provide additional data for assessing the current state of the labor market.