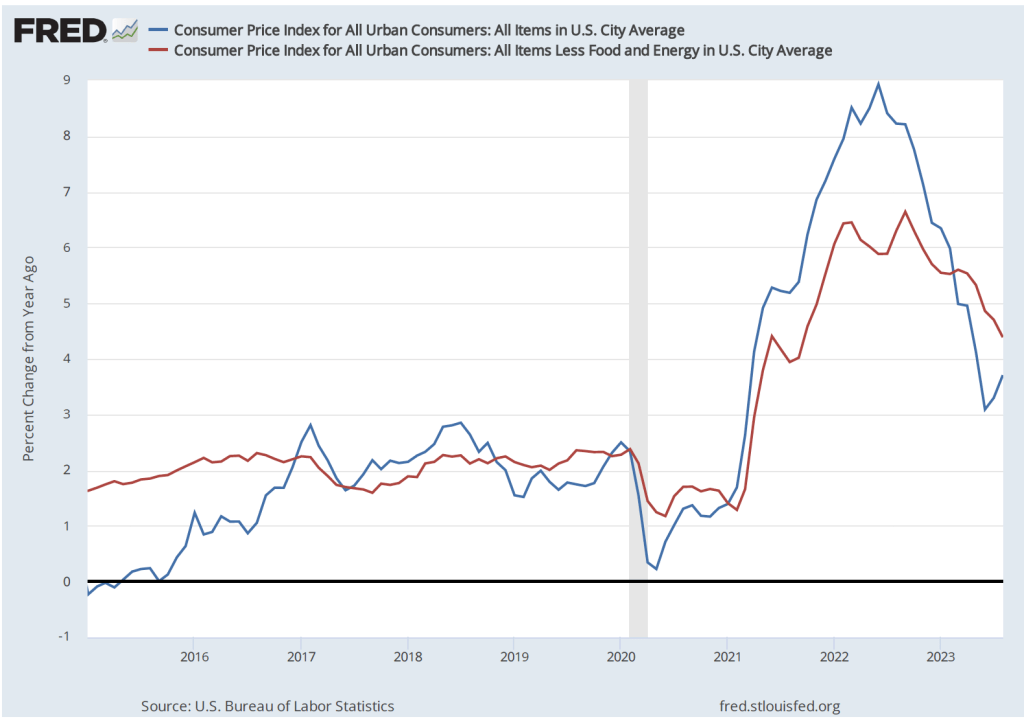

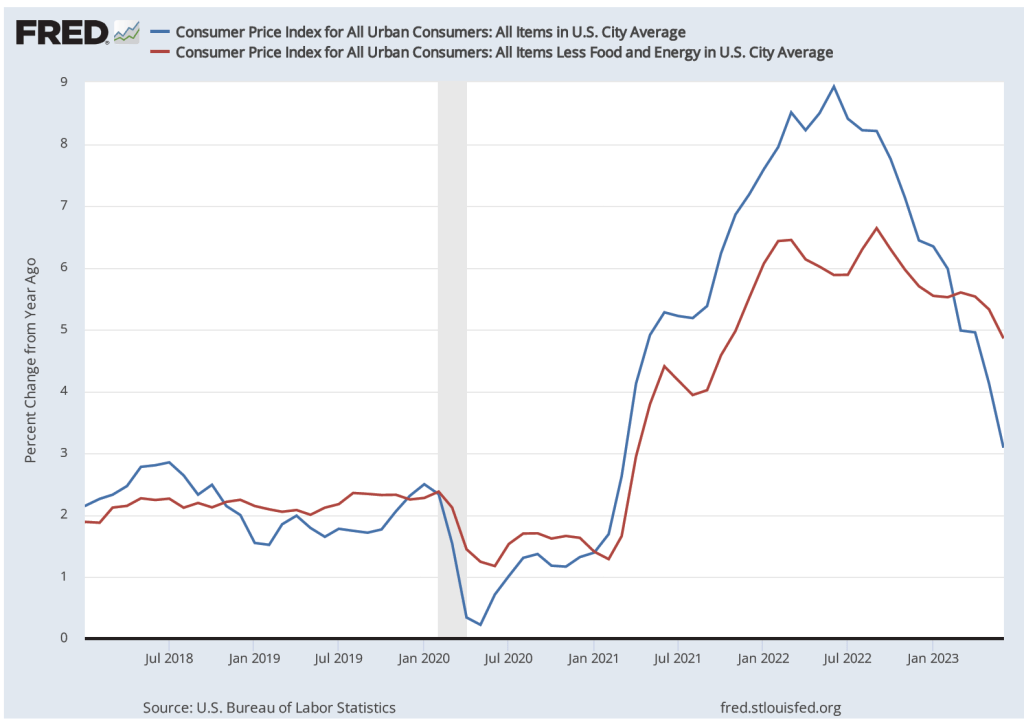

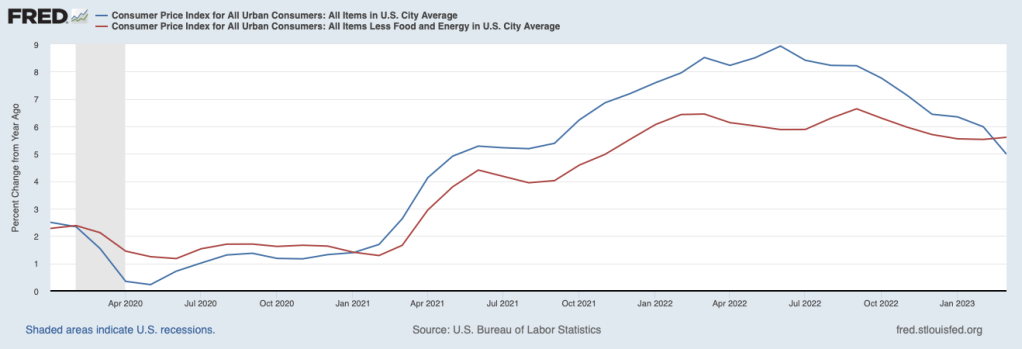

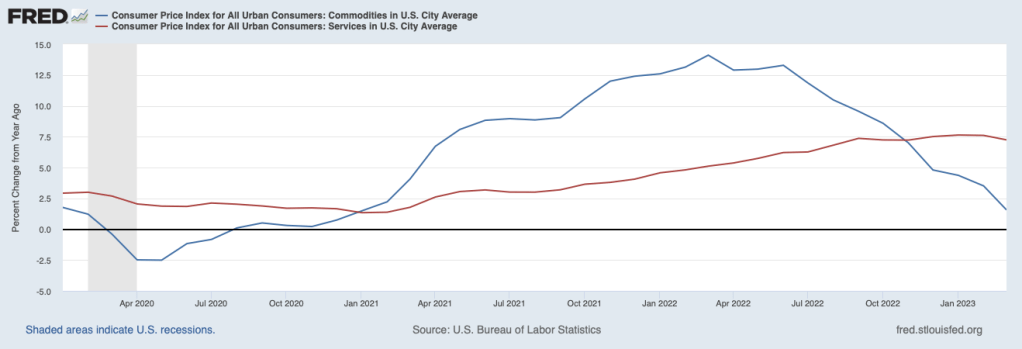

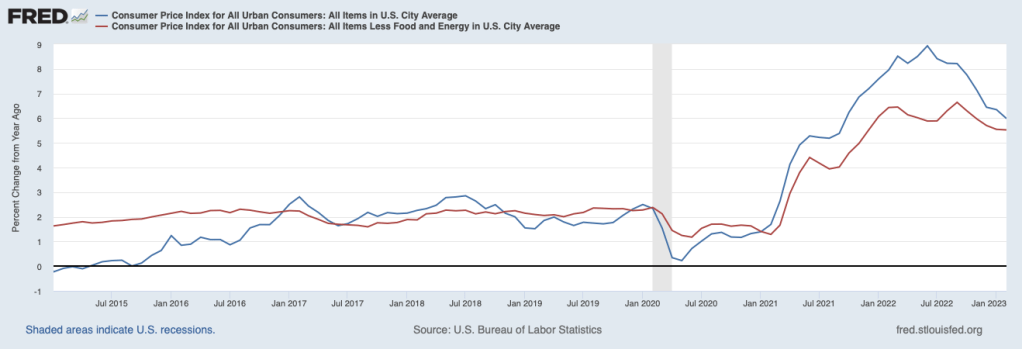

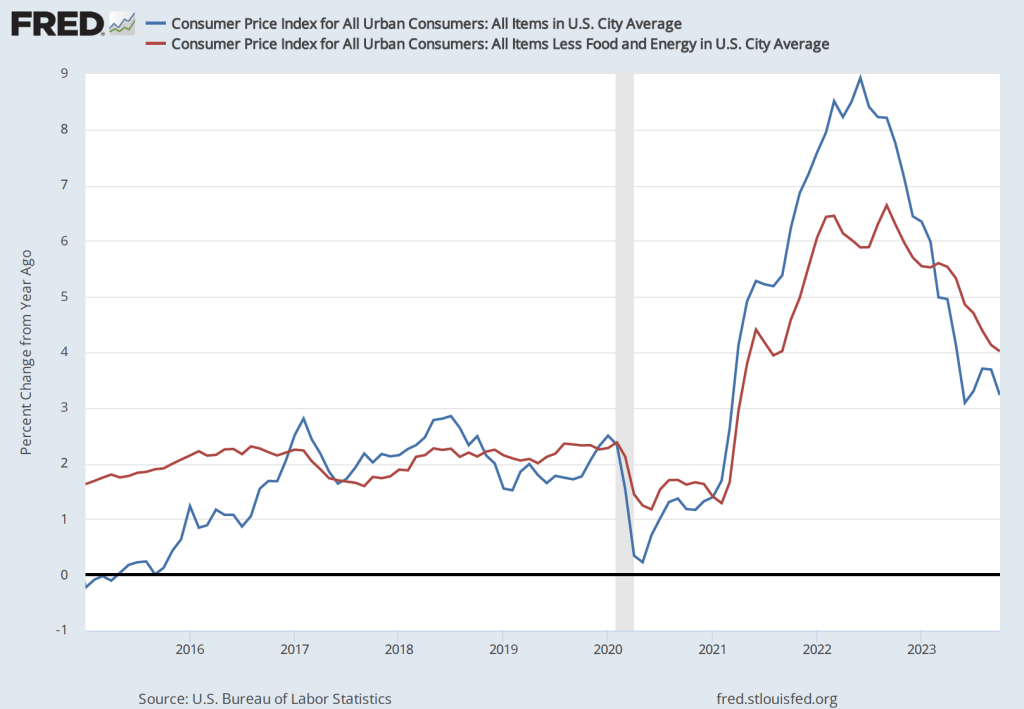

The Bureau of Labor Statistics released its latest report on consumer prices the morning of November 14. The Wall Street Journal’s headline reflects the general reaction to the report: The inflation rate continued to decline, which made it less likely that the Fed’s Federal Open Market Committee will raise its target range for the federal funds rate again at its December meeting. The following figure shows inflation measured as the percentage change in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) from the same month in the previous year. It also shows the inflation rate measure using “core” CPI, which excludes prices for food and energy.

The inflation rate for the CPI declined from 3.7 percent in September to 3.2 percent in October. Core CPI declined from 4.1 percent in September to 4.0 percent in October. So, measured this way, inflation declined substantially when measured by the CPI including prices of all goods and services but only slightly when measured using core CPI.

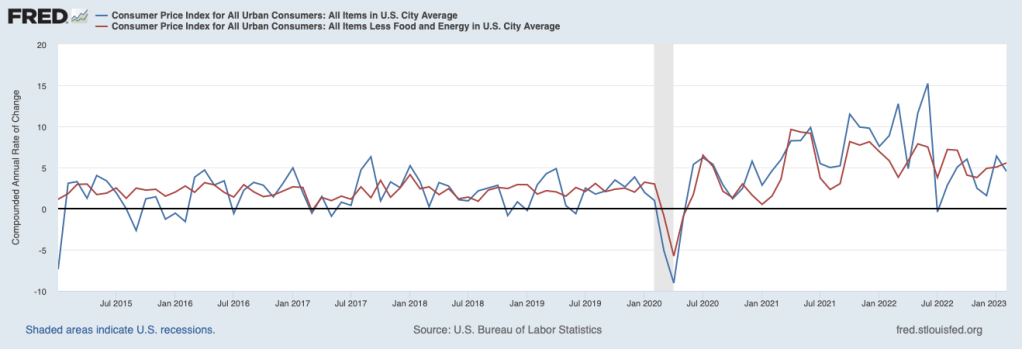

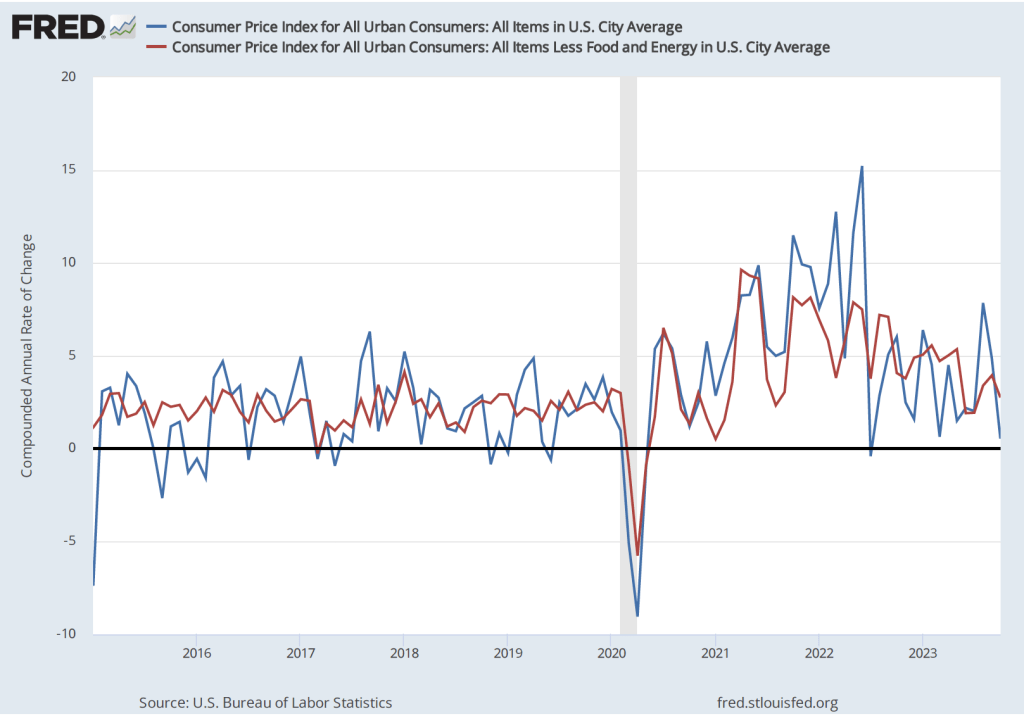

The 12-month inflation rate is the one typically reported in the Wall Street Journal and elsewhere, but it has the drawback that it doesn’t always reflect accurately the current trend in prices. The following figure shows the 1-month inflation rate—that is the annual inflation rate calculated by compounding the current month’s rate over an entire year— for CPI and core CPI. The 1-month inflation rate is naturally more volatile than the 12-month inflation rate. In this case, 1-month rate shows a sharp decline in the inflation rate for the CPI from 4.9 percent in September to 0.5 percent in October. Core inflation declined less sharply from 3.9 percent in September to 2.8 percent in October.

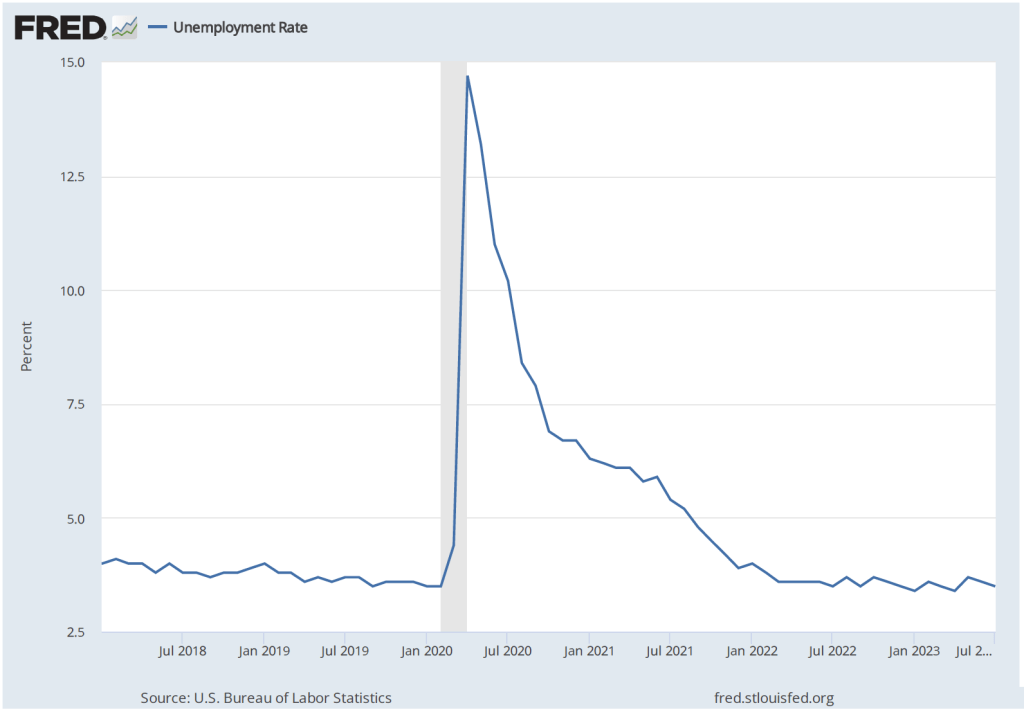

The release of the CPI report was treated as good news on Wall Street, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average increasing by 500 points and the interest rate on the 10-year U.S. Treasury Note declining from 4.6 percent just before the report was released to 4.4 percent immediately after. The increases in stock and bond prices (recall that the prices of bonds and the yields on the bonds move in opposite directions, so bond prices rose following release of the report) reflect the view of financial investors that if the FOMC stops increasing its target for the federal funds rate, the chance that the U.S. economy will fall into a recession is reduced.

A word of caution, however. In a speech on November 9, Fed Chair Jerome Powell noted that the FOMC may need still need to implement additional increases to its federal funds rate target:

“My colleagues and I are gratified by this progress [against inflation] but expect that the process of getting inflation sustainably down to 2 percent has a long way to go…. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is committed to achieving a stance of monetary policy that is sufficiently restrictive to bring inflation down to 2 percent over time; we are not confident that we have achieved such a stance. We know that ongoing progress toward our 2 percent goal is not assured: Inflation has given us a few head fakes. If it becomes appropriate to tighten policy further, we will not hesitate to do so.”

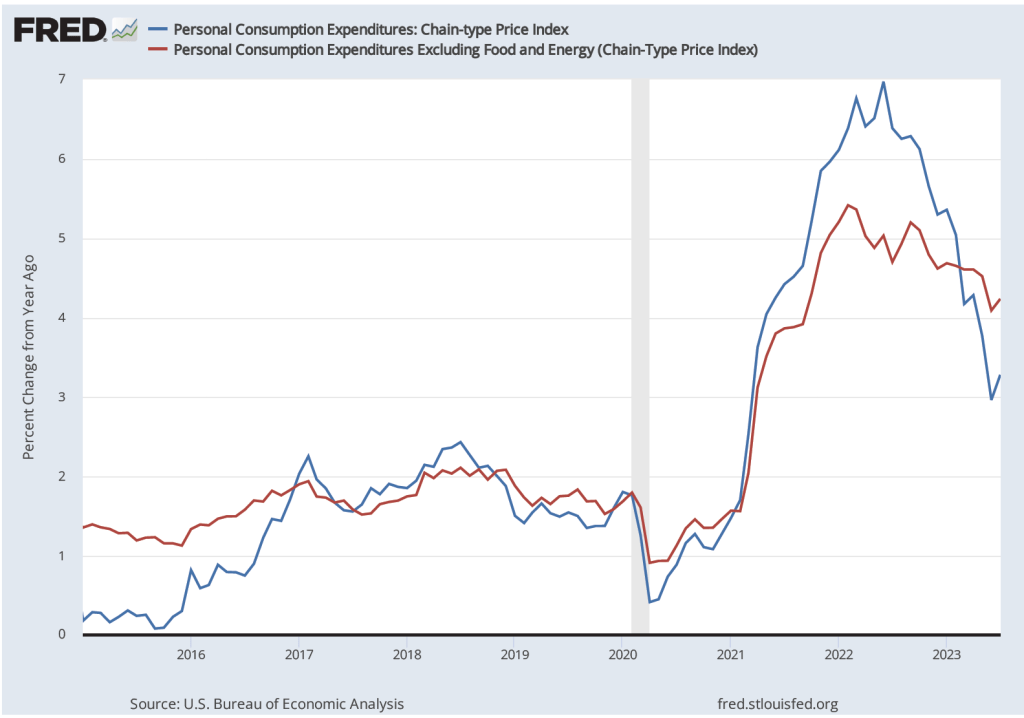

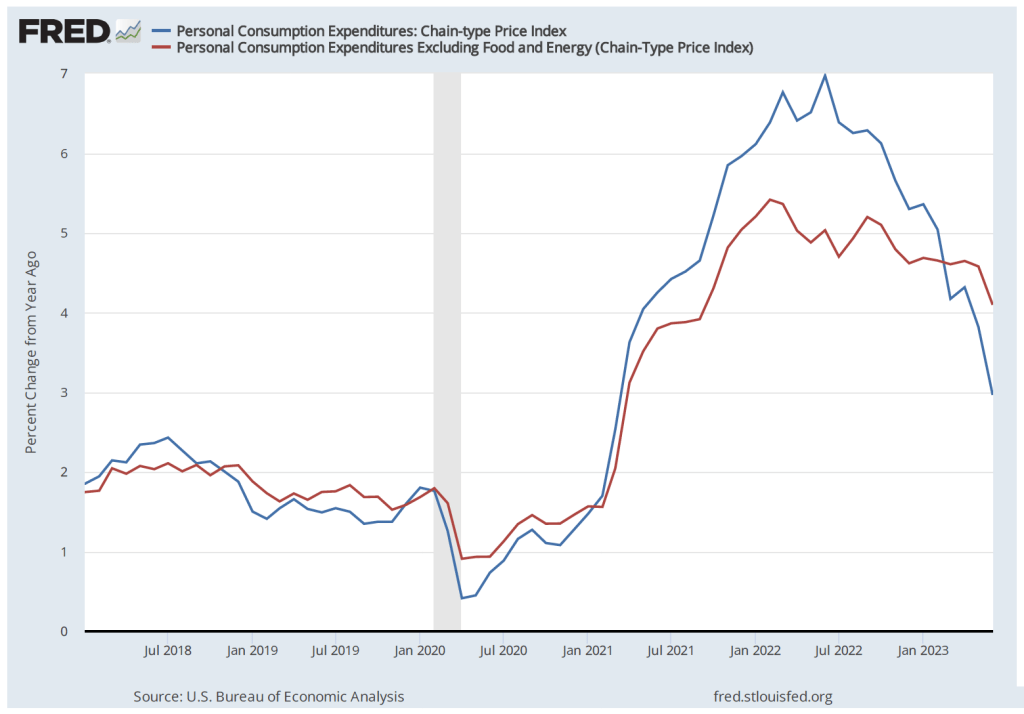

So, while the latest inflation report is good news, it’s still too early to know whether inflation is on a stable path to return to the Fed’s 2 percent target. (It’s worth noting that the Fed uses inflation as measured by the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) price index rather than as measured by the CPI when evaluating whether it has achieved its 2 percent target.)