Arthur Burns was Fed chair during the stagflation of the 1970s. (Photo from the Wall Street Journal)

This morning, Thursday April 25, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) released its advance estimate of real GDP growth during the first quarter of 2024. The two most striking points in the report are, first, that real GDP increased in the first quarter at an annual rate of only 1.6 percent—well below the 2.5 percent increase expected in a survey of economists and the 2.7 percent increase indicated by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s GDPNow forecast. As the following figure shows, the growth rate of real GDP has declined in each of the last two quarters from the very strong growth rate of 4.9 percent during the third quarter of 2023.

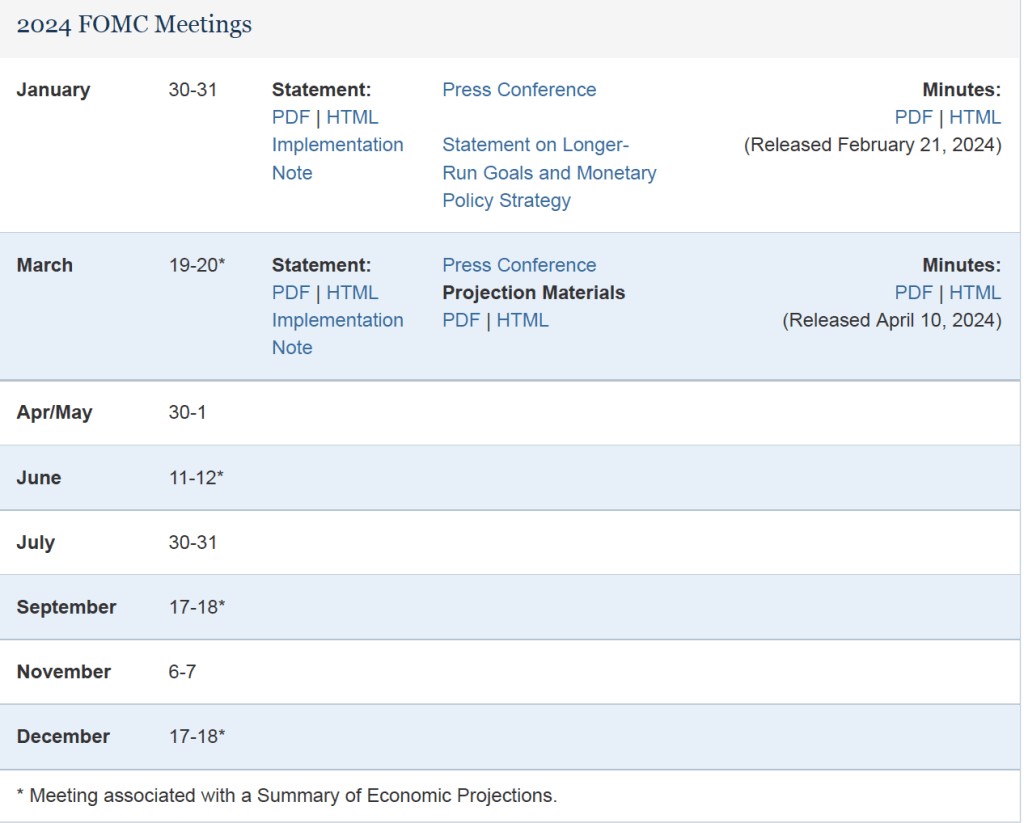

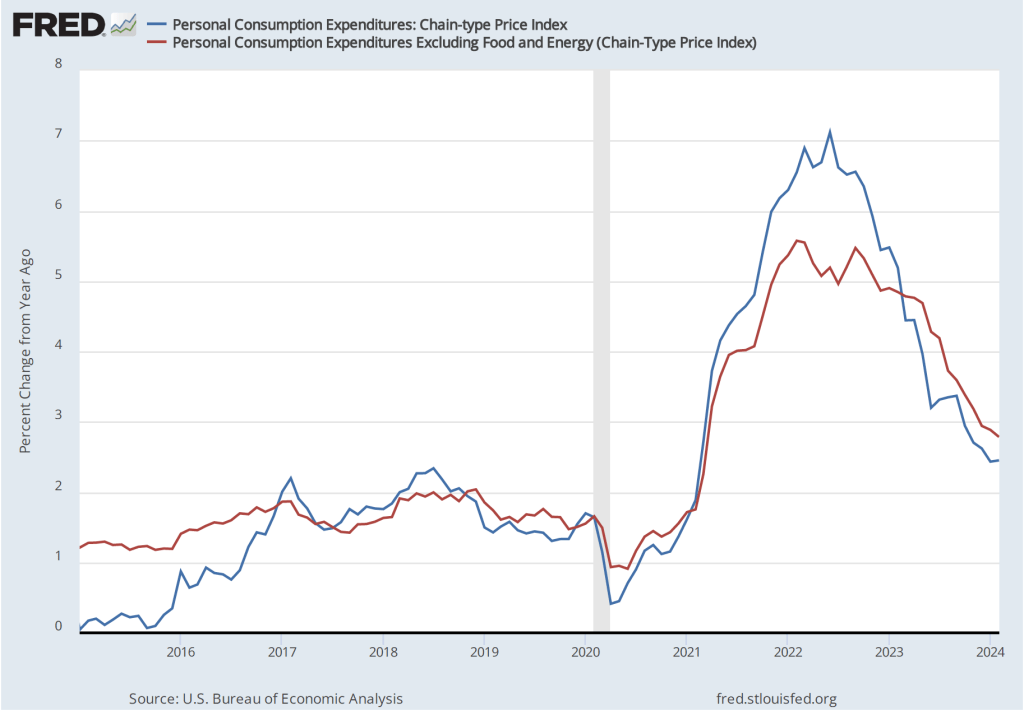

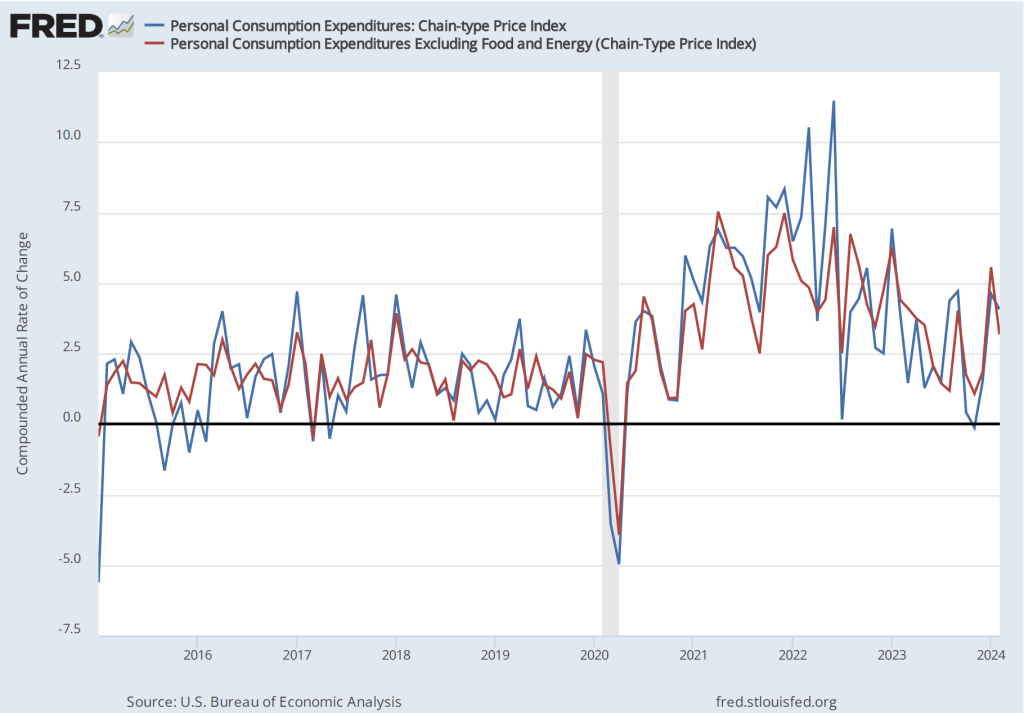

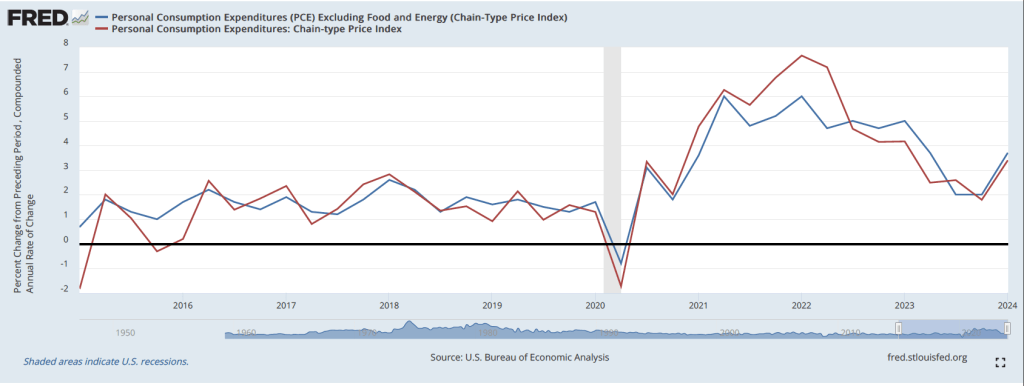

The second striking point in the report was an unexpected increase in inflation, as measured using the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index. As the following figure shows, PCE inflation (the red line), measured as a compound annual rate of change, increased from 1.8 percent in the fourth quarter of 2023 to 3.4 percent in the first quarter of 2024. Core PCE inflation (the blue line), which excludes food and energy prices, increased from 2.0 percent in the fourth quarter of 2023 to 3.7 percent in the first quarter of 2024. These data indicate that inflation in the first quarter of 2024 was running well above the Federal Reserve’s 2.0 percent target.

A combination of weak economic growth and above-target inflation poses a policy dilemma for the Fed. As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 13, Section 13.3 (Economics, Chapter 23, Section 23.3), the combination of slow growth and inflation is called stagflation. During the 1970s, when the U.S. economy suffered from stagflation, Fed Chair Arthur Burns (whose photo appears at the beginning of this post) was heavily criticized by members of Congress for his inability to deal with the problem. Stagflation poses a dilemma for the Fed because using an expansionary monetary policy to deal with slow economic growth may cause the inflation rate to rise. Using a contractionary monetary policy to deal with high inflation can cause growth to slow further, possibly pushing the economy into a recession.

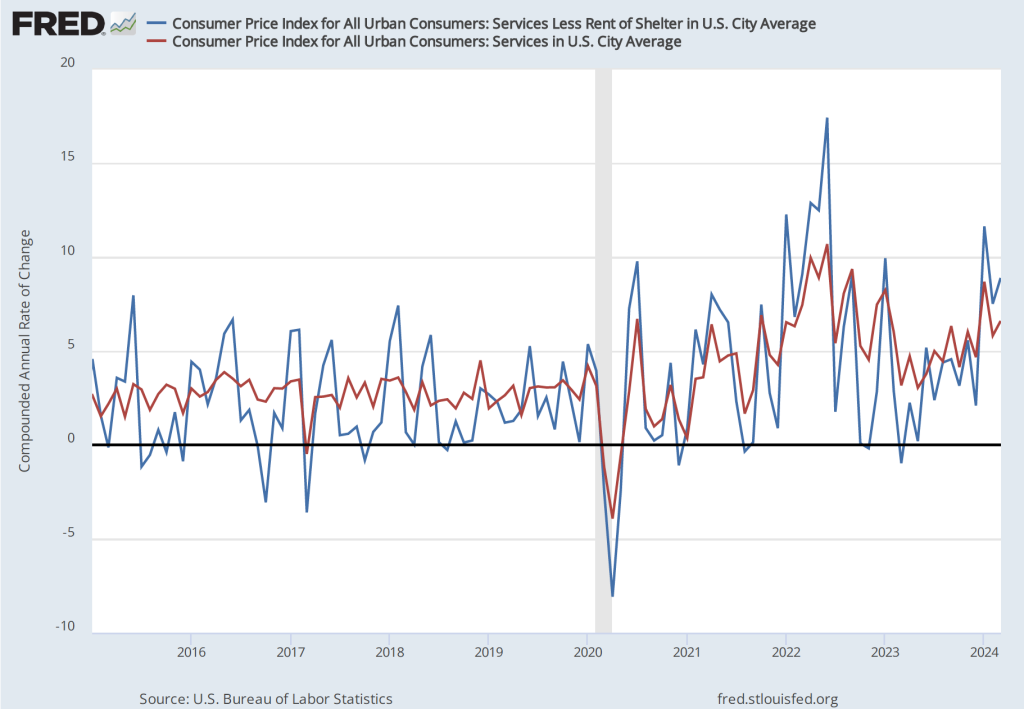

Is Fed Chair Jerome Powell in as difficult a situation as Arthur Burns was in the 1970s? Not yet, at least. First, Burns faced a period of recession—declining real GDP and rising unemployment—whereas currently, although economic growth seems to be slowing, real GDP is still rising and the unemployment rate is still below 4 percent. In addition, the inflation rate in these data are below 4 percent, far less than the 10 percent inflation rates during the 1970s.

Second, it’s always hazardous to draw conclusions on the basis of a single quarter’s data. The BEA’s real GDP estimates are revised several times, so that the value for the first quarter of 2024 may well be revised significantly higher (or lower) in coming months.

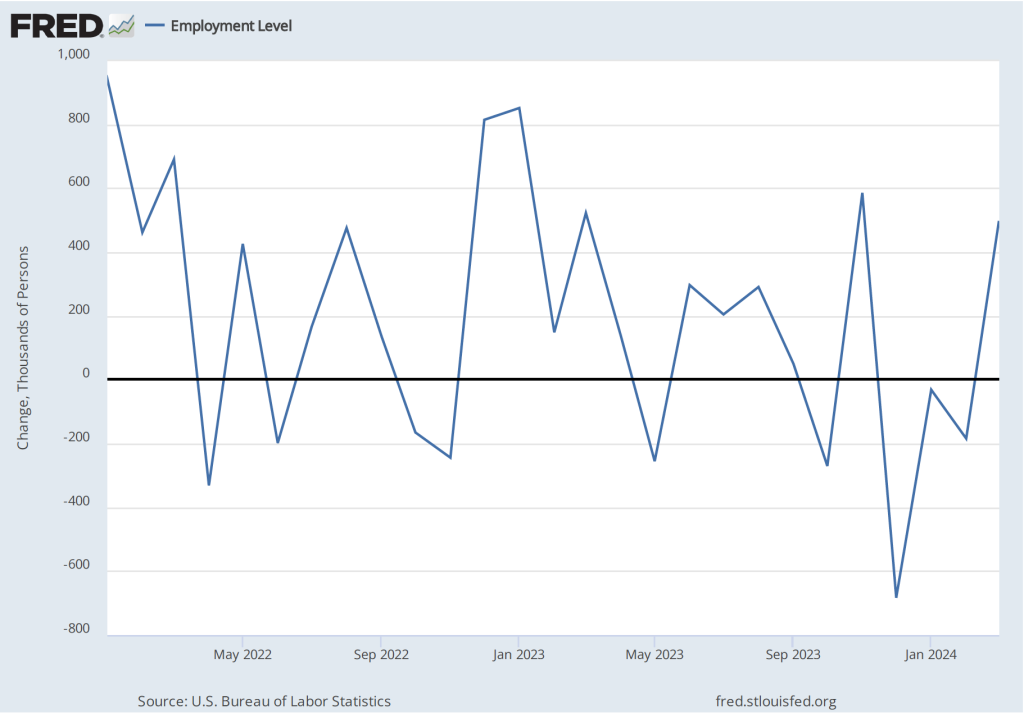

Third, the slow rate of growth of real GDP in the first quarter is accounted for largely by a surge in imports—which are subtracted from GDP—and a sharp decline in inventory investment. Key components of aggregate demand remained strong: Consumption expenditures increased at annual rate of 2.5 per cent and business investment increased at an annual rate of 3.2 percent. Residential investment was particularly strong, growing at an annual rate 0f 13.2 percent—despite the effects of rising mortgage interest rates. One way to strip out the effects of net exports, inventory investment, and government purchases—which can also be volatile—is to look at final sales to domestic purchasers, which includes only spending by U.S. households and firms on domestic production. As the following figure shows, real final sales to domestic purchasers declined only modertately from 3.3 percent in the fourth quarter of 2023 to 3.1 percent in the first quarter of 2024.

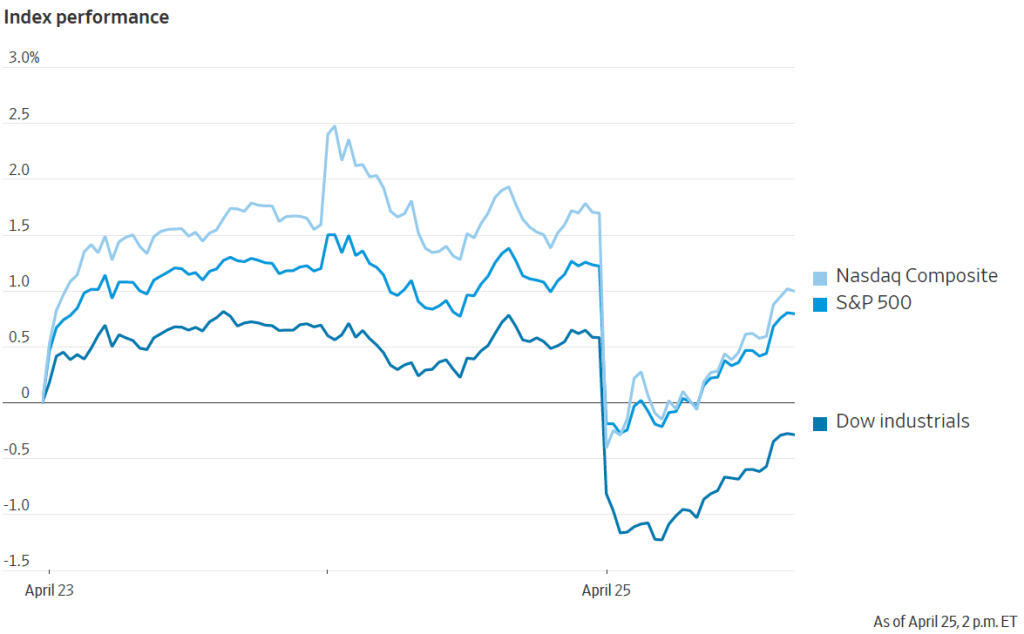

Looking at these details of the GDP report indicate that growth may have slowed less during the first quarter than the growth rate of real GDP seems to indicate. Investors on Wall Street may have come to this same conclusion. As shown by this figure from the Wall Street Journal, shows that stock prices fell sharply when trading opened at 9:30 am, but by 2 pm has recovered some of their losses as investors considered further the implications of the GDP report. (As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 6, Section 6.2 and Economics, Chapter 8, Section 8.2, movements in stock price indexes can provide some insight into investors’ expectations of future movements in corporate profits, which, in turn, depend in part on future movements in economic growth.)

Finally, we may get more insight into the rate of inflation tomorrow morning when the BEA releases its report on “Personal Income and Outlays,” which will include data on PCE inflation during March. The monthly PCE data provide more current information than do the quarterly data in the GDP report.

In short, today’s report wasn’t good news, but may not have been as bad as it appeared at first glance. We are far from being able to conclude that the U.S. economy is entering into a period of stagflation.