Image created by GPT

Most large firms selling consumer goods continually evaluate which new products they should introduce. Managers of these firms are aware that if they fail to fill a market niche, their competitors or a new firm may develop a product to fill the niche. Similarly, firms search for ways to improve their existing products.

For example, Ferrara Candy, had introduced Nerds in 1983. Although Nerds experienced steady sales over the following years, company managers decided to devote resources to improving the brand. In 2020, they introduced Nerds Gummy Clusters, which an article in the Wall Street Journal describes as being “crunchy outside and gummy inside.” Over five years, sales of Nerds increased from $50 millions to $500 million. Although the company’s market research “suggested that Nerds Gummy Clusters would be a dud … executives at Ferrara Candy went with their guts—and the product became a smash.”

Image of Nerds Gummy Clusters from nerdscandy.com

Firms differ on the extent to which they rely on market research—such as focus groups or polls of consumers—when introducing a new product or overhauling an existing product. Henry Ford became the richest man in the United States by introducing the Model T, the first low-priced and reliable mass-produced automobile. But Ford once remarked that if before introducing the Model T he had asked people the best way to improve transportation they would probably have told him to develop a faster horse. (Note that there’s a debate as to whether Ford ever actually made this observation.) Apple co-founder Steve Jobs took a similar view, once remaking in an interview that “it’s really hard to design products by focus groups. A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.” In another interview, Jobs stated: “We do no market research. We don’t hire consultants.”

Unsurprisingly, not all new products large firms introduce are successful—whether the products were developed as a result of market research or relied on the hunches of a company’s managers. To take two famous examples, consider the products shown in image at the beginning of this post—“New Coke” and the Ford Edsel.

Pepsi and Coke have been in an intense rivalry for decades. In the 1980s, Pepsi began to gain market share at Coke’s expense as a result of television commercials showcasing the “Pepsi Challenge.” The Pepsi Challenge had consumers choose from colas in two unlabeled cups. Consumers overwhelming chose the cup containing Pepsi. Coke’s management came to believe that Pepsi was winning the blind taste tests because Pepsi was sweeter than Coke and consumers tend to favor sweeter colas. In 1985, Coke’s managers decided to replace the existing Coke formula—which had been largely unchanged for almost 100 years—with New Coke, which had a sweeter taste. Unfortunately for Coke’s managers, consumers’ reaction to New Coke was strongly negative. Less than three months later, the company reintroduced the original Coke, now labeled “Coke Classic.” Although Coke produced both versions of the cola for a number of years, eventually they stopped selling New Coke.

Through the 1920s, the Ford Motor Company produced only two car models—the low-priced Model T and the high-priced Lincoln. That strategy left an opening for General Motors during the 1920s to introduce a variety of car models at a number of price levels. Ford scrambled during the 1930s and after the end of World War II in 1945 to add new models that would compete directly with some of GM’s models. After a major investment in new capacity and an elaborate marketing campaign, Ford introduced the Edsel in September 1957 to compete against GM’s mid-priced models: Pontiac, Oldsmobile, and Buick.

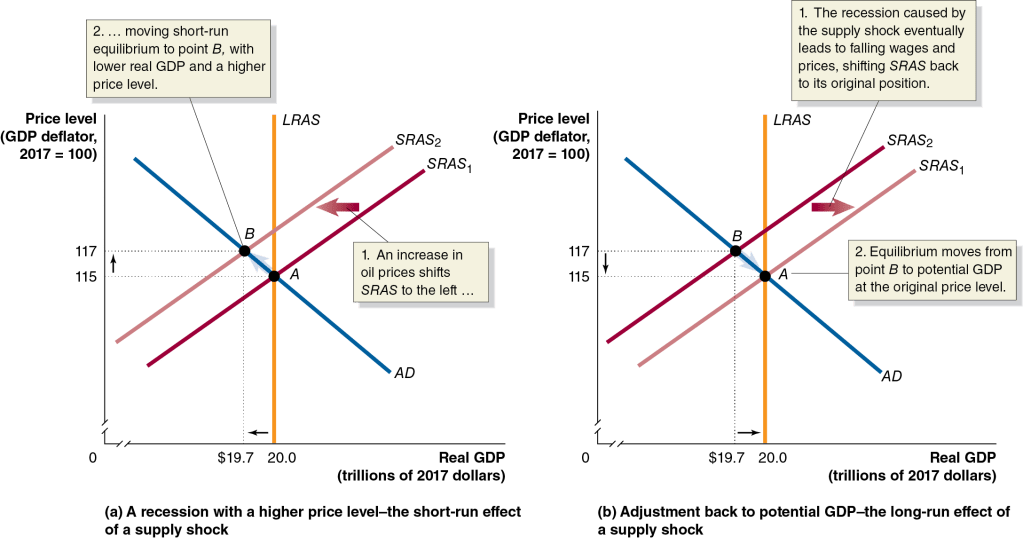

Unfortunately, the Edsel was introduced during a sharp, although relatively short, economic recession. As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 13 (Economics, Chapter 23), consumers typically cut back on purchases of consumer durables like automobiles during a recession. In addition, the Edsel suffered from reliability problems and many consumers disliked the unusual design, particularly of the front of the car. Consumers were also puzzled by the name Edsel. Ford CEO Henry Ford II was the grandson of Henry Ford and the son of Edsel Ford, who had died in 1943. Henry Ford II named in the car in honor of his father but the unusual name didn’t appeal to consumers. Ford ceased production of the car in November 1959 after losing $250 million, which was one of the largest losses in business history to that point. The name “Edsel” has lived on as a synonym for a disastrous product launch.

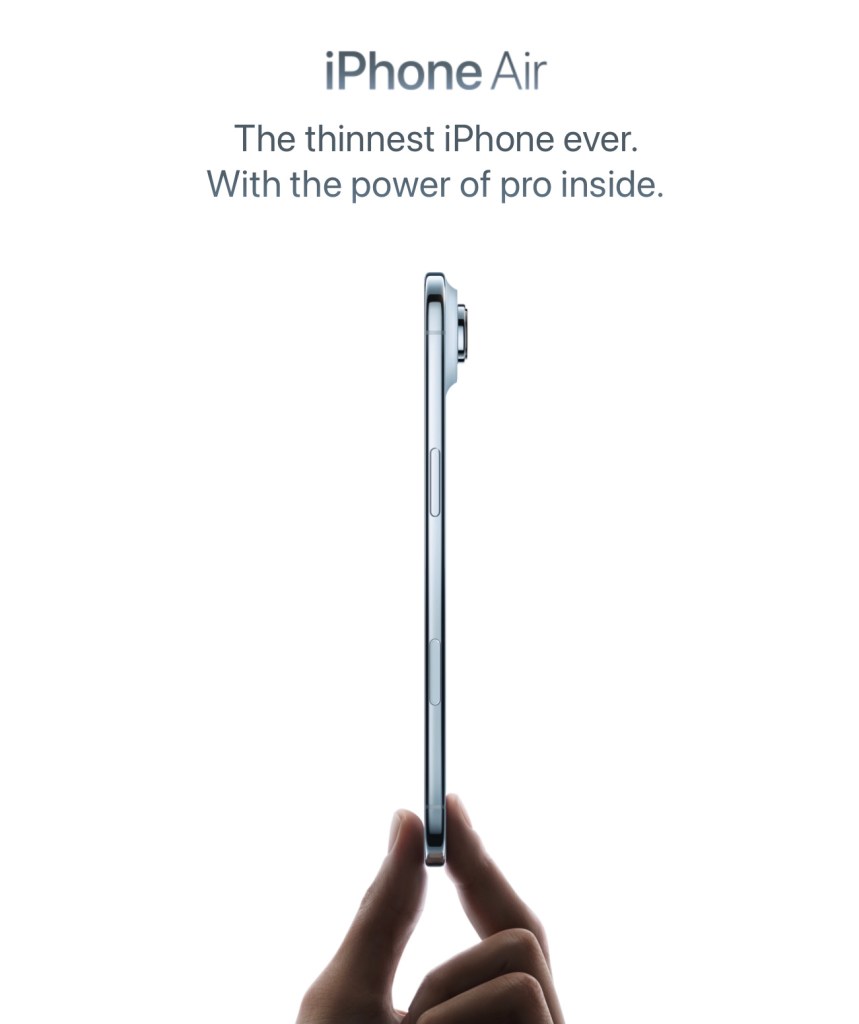

Image of iPhone Air from apple.com

Apple earns about half of its revenue and more than half of its profit from iPhone sales. Making sure that it is able to match or exceed the smartphone features offered by competitors is a top priority for CEO Tim Cook and other Apple managers. Because Apple’s iPhones are higher-priced than many other smartphones, Apple has tried various approaches to competing in the market for lower-priced smartphones.

In 2013, Apple was successful in introducing the iPad Air, a thinner, lower-priced version of its popular iPad. Apple introduced the iPhone Air in September 2025, hoping to duplicate the success of the iPad Air. The iPhone Air has a titanium frame and is lighter than the regular iPhone model. The Air is also thinner, which means that its camera, speaker, and its battery are all a step down from the regular iPhone 17 model. In addition, while the iPhone Air’s price is $100 lower than the iPhone 17 Pro, it’s $200 higher than the base model iPhone 17.

Unlike with the iPad Air, Apple doesn’t seem to have aimed the iPhone Air at consumers looking for a lower-priced alternative. Instead, Apple appears to have targeted consumers who value a thinner, lighter phone that appears more stylish, because of its titanium frame, and who are willing to sacrifice some camera and sound quality, as well as battery life. An article in the Wall Street Journal declared that: “The Air is the company’s most innovative smartphone design since the iPhone X in 2017.” As it has turned out, there are apparently fewer consumers who value this mix of features in a smartphone than Apple had expected.

Sales were sufficiently disappointing that within a month of its introduction, Apple ordered suppliers to cut back production of iPhone Air components by more than 80 percent. Apple was expected to produce 1 million fewer iPhone Airs during 2025 than the company had initially planned. An article in the Wall Street Journal labeled the iPhone Air “a marketing win and a sales flop.” According to a survey by the KeyBanc investment firm there was “virtually no demand for [the] iPhone Air.”

Was Apple having its New Coke moment? There seems little doubt that the iPhone Air has been a very disappointing new product launch. But its very slow sales haven’t inflicted nearly the damage that New Coke caused Coca-Cola or that the Edsel caused Ford. A particularly damaging aspect of New Coke was that was meant as a replacement for the existing Coke, which was being pulled from production. The result was a larger decline in sales than if New Coke had been offered for sale alongside the existing Coke. Similarly, Ford set up a whole new division of the company to produce and sell the Edsel. When Edsel production had to be stopped after only two years, the losses were much greater than they would have been if Edsel production hadn’t been planned to be such a large fraction of Ford’s total production of automobiles.

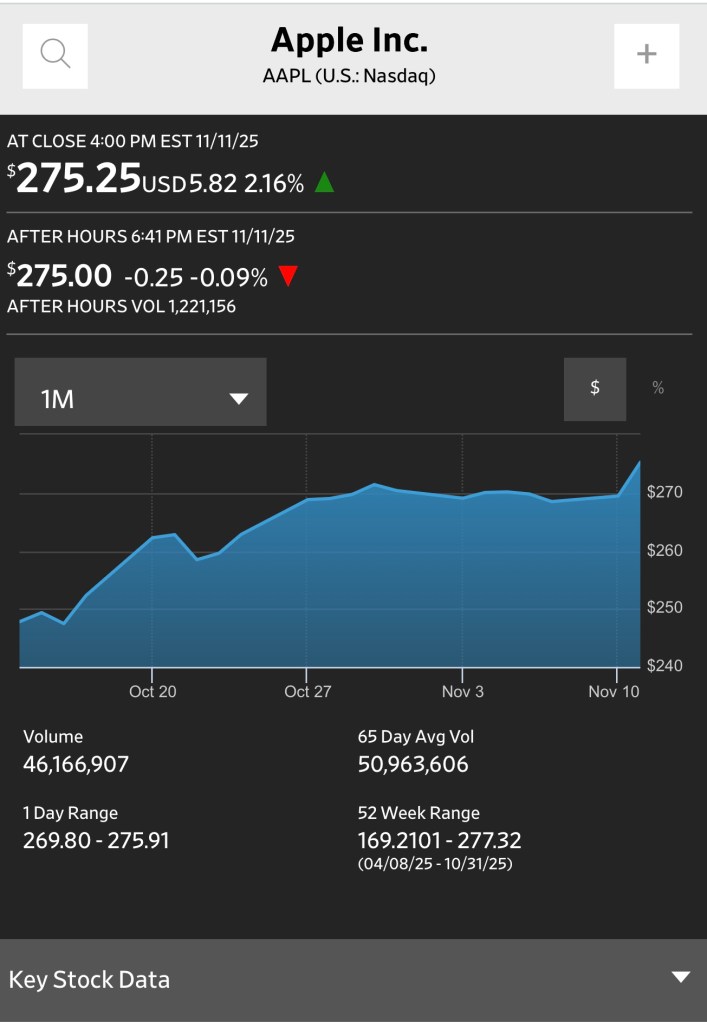

Although very slow iPhone Air sales have caused Apple to incur losses on the model, the Air was meant to be one of several iPhone models and not the only iPhone model. Clearly investors don’t believe that problems with the Air will matter much to Apple’s profits in the long run. The following graphic from the Wall Street Journal shows that Apple’s stock price has kept rising even after news of serious problems with Air sales became public in late October.

So, while the iPhone Air will likely go down as a failed product launch, it won’t achieve the legendary status of New Coke or the Edsel.