Image generated by GTP-4o of someone searching online for a job

It’s become clear during the past few years that most people really, really, really don’t like inflation. Dating as far back as the 1930s, when very high unemployment rates persisted for years, many economists have assumed that unemployment is viewed by most people as a bigger economic problem than inflation. Bu the economic pain from unemployment is concentrated among those people who lose their jobs—and their families—although some people also have their hours reduced by their employers and in severe recessions even people who retain their jobs can be afraid of being laid off.

Although nearly everyone is affected by an increase in the inflation rate, the economic losses are lower than those suffered by people who lose their jobs during a period in which it may difficult to find another one. In addition, as we note in Macroeconomics, Chapter 9, Section 9.7 (Economics, Chapter 19, Section 19.7), that:

“An expected inflation rate of 10 percent will raise the average price of goods and services by 10 percent, but it will also raise average incomes by 10 percent. Goods and services will be as affordable to an average consumer as they would be if there were no inflation.”

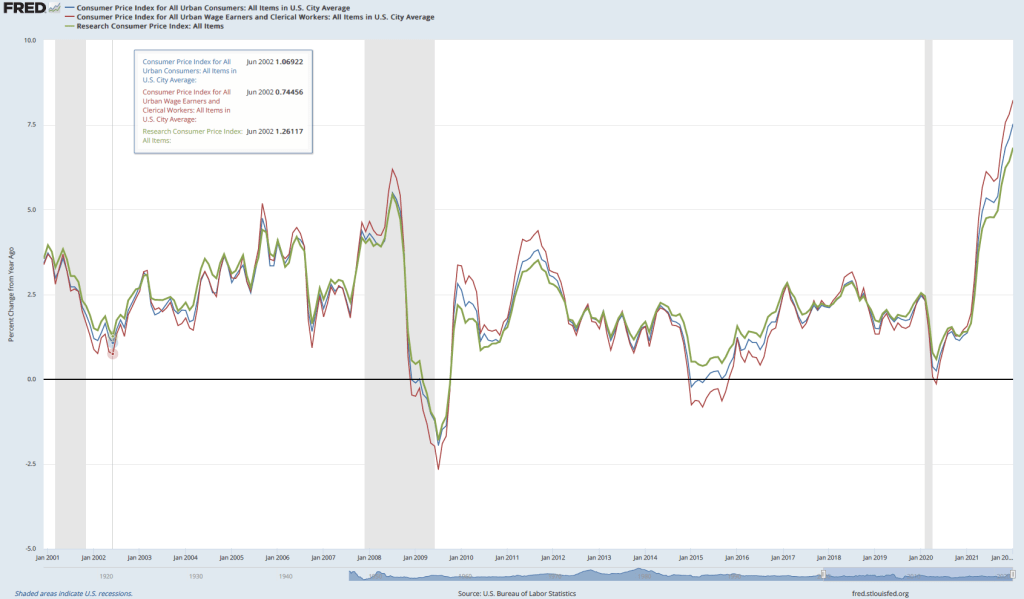

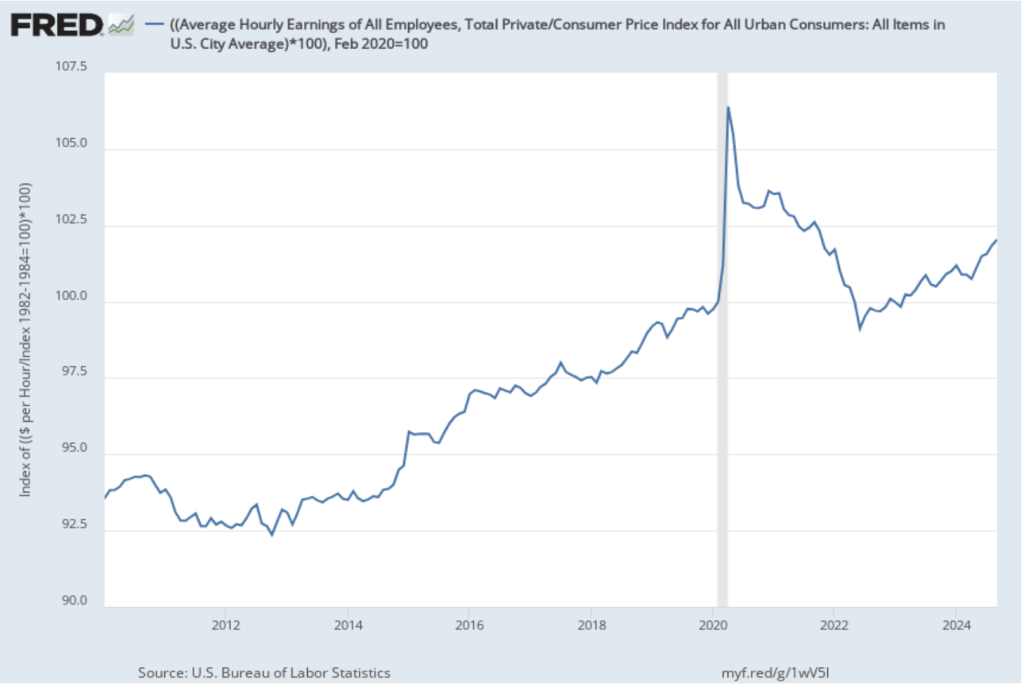

In other words, inflation affects nominal variables, but over the long run inflation won’t affect real variables such as the real wage, employment, or the real value of output. The following figure shows movements in real wages from January 2010 through September 2024. Real wages are calculated as nominal average hourly earnings deflated by the consumer price index, with the value for February 2020—the last month before the effects of the Covid pandemic began affecting the United States—set equal to 100. Measured this way, real wages were 2 percent higher in September 2024 than in February 2020. (Although note that real wages were below where they would have been if the trend from 2013 to 2020 had continued.)

Although increases in wages do keep up with increases in prices, many people doubt this point. In Chapter 17, Section 17.1, we discuss a survey Nobel Laurete Rober Shiller of Yale conducted of the general public’s views on inflation. He asked in the survey how “the effect of general inflation on wages or salary relates to your own experience or your own job.” The most populat response was: “The price increase will create extra profifs for my employer, who can now sell output for more; there will be no increase in my pay. My employer will see no reason to raise my pay.”

Recently, Stefanie Stantcheva of Harvard conducted a survey similar to Schiller’s and received similar responses:

“If there is a single and simple answer to the question ‘Why do we dislike inflation,’ it is because many individuals feel that it systematically erodes their purchasing power. Many people do not perceive their wage increases sufficiently to keep up with inflation rates, and they often believe that wages tend to rise at a much slower rate compared to prices.”

A recent working paper by Joao Guerreiro of UCLA, Jonathon Hazell of the London School of Economics, Chen Lian of UC Berkeley, and Christina Patterson of the University of Chicago throws additional light on the reasons that people are skeptical that once the market adjusts, their wages will keep up with inflation. Economists typically think of the real wage as adjusting to clear the labor market. If inflation temporarily reduces the real wage, the nominal wage will increase to restore the market-clearing value of the real wage.

But the authors of thei paper note that, in practice, to receive an increase in your nominal wage you need to either 1)ask your employer to increase your wage, or 2) find another job that pays a higher nominal wage. They note that both of these approachs result in “conflict”: “We argue that workers must take costly actions (‘conflict’) to have nominal wages catch up with inflation, meaning there are welfare costs even if real wages do not fall as inflation rises.” The results of a survey they undertook revealed that:

“A significant portion of workers say they took costly actions—that is, they engaged in conflict—to achieve higher wage growth than their employer offered. These actions include having tough conversations with employers about pay, partaking in union activity, or soliciting job offers.”

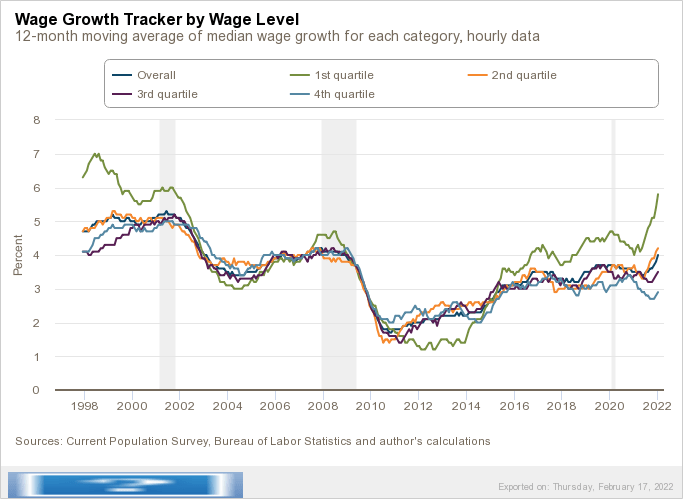

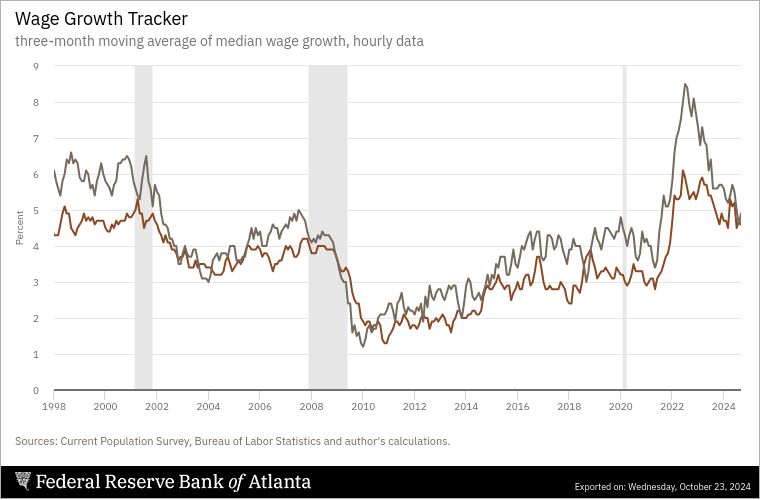

Their result is consistent with data showing that workers who switch jobs receive larger wage increases than do workers who remain in their jobs. The following figure is from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland and shows the increase in the median nominal hourly wage over the previous year for workers who stayed in their job over that period (brown line) and for workers who switched jobs (gray line).

Job switchers consistently earn larger wage increases than do job stayers with the difference being particularly large during the high inflation period of 2022 and 2023. For instance, in July 2022, job switchers earned average wage increases of 8.5 percent compared with average increases of 5.9 percent for job stayers.

The fact that to keep up with inflation workers have to either change jobs or have a potentially contentious negotiation with their employer provides another reason why the recent period of high inflation led to widespread discontent with the state of the U.S. economy.