Photo from federalreserve.gov

This opinion column originally ran at Project Syndicate.

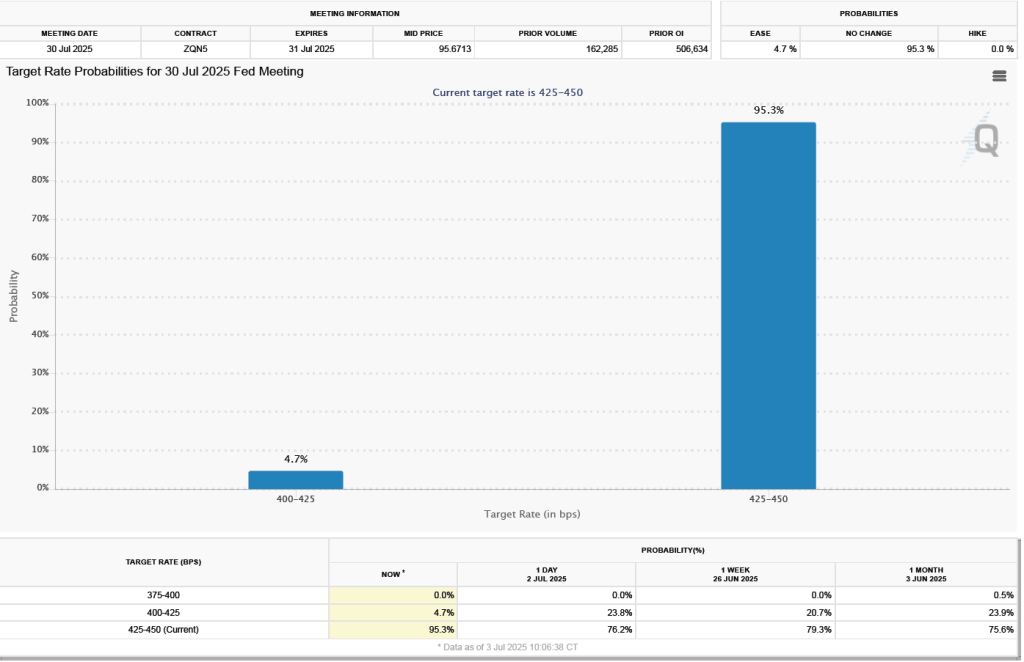

While recent media coverage of the US Federal Reserve has tended to focus on when, and by how much, interest rates will be cut, larger issues loom. The selection of a new Fed chair to succeed Jerome Powell, whose term ends next May, should focus not on short-term market considerations, but on policies and processes that could improve the Fed’s overall performance and accountability.

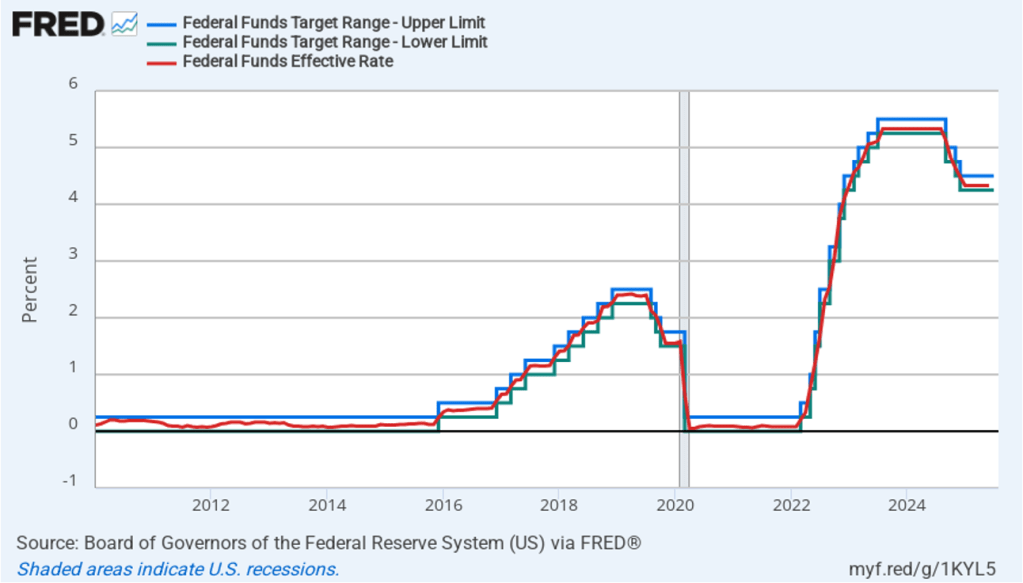

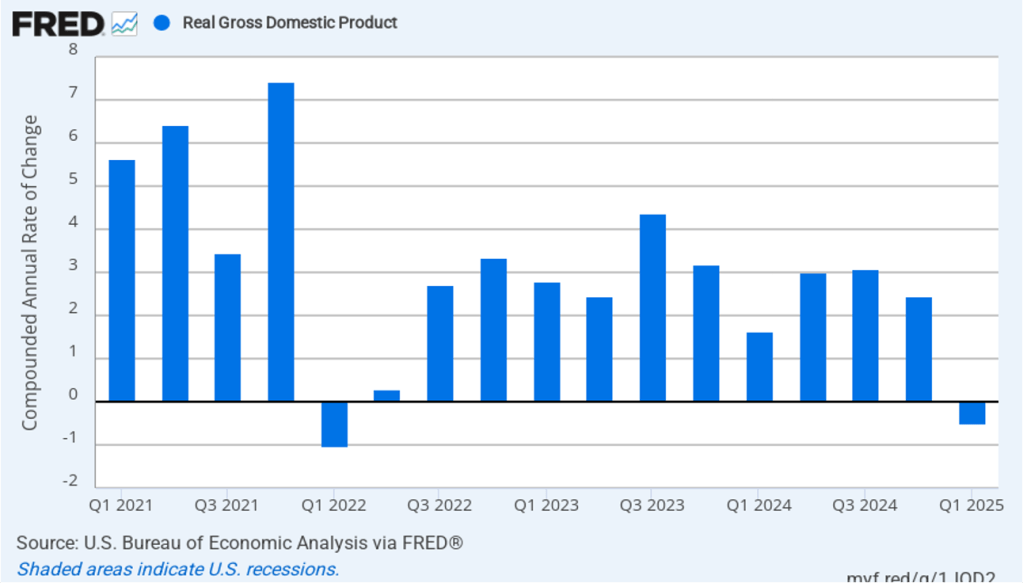

By demanding that the Fed cut the federal funds rate sharply to boost economic activity and lower the government’s borrowing costs, US President Donald Trump risks pushing the central bank toward an overly inflationary monetary policy. And that, in turn, risks increasing the term premium in the ten-year Treasury yield—the very financial indicator that Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has emphasized. A higher premium would raise, not lower, borrowing costs for the federal government, households, and businesses alike. Moreover, concerns about the Fed’s independence in setting monetary policy could undermine confidence in US financial markets and further weaken the dollar’s exchange rate.

But this does not imply that Trump should simply seek continuity at the Fed. The Fed, under Powell, has indeed made mistakes, leading to higher inflation, sometimes inept and uncoordinated communications, and an unclear strategy for monetary policy.

I do not share the opinion of Trump and his advisers that the Fed has acted from political or partisan motives. Even when I have disagreed with Fed officials or Powell on matters of policy, I have not doubted their integrity. However, given their mistakes, I do believe that some institutional introspection is warranted. The next chair—along with the Board of Governors and the Federal Open Market Committee—will have many policy questions to address beyond the near-term path for the federal funds rate.

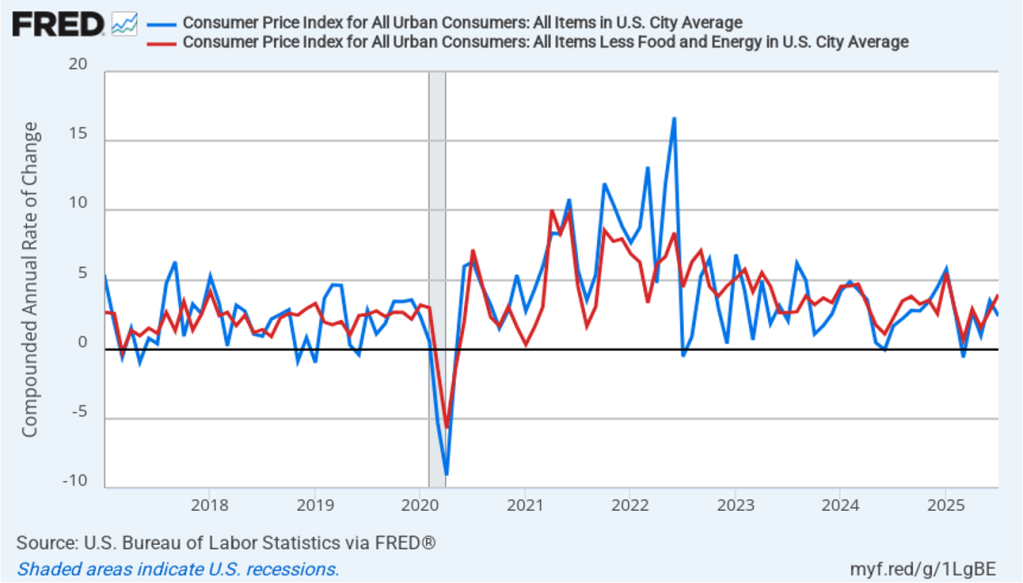

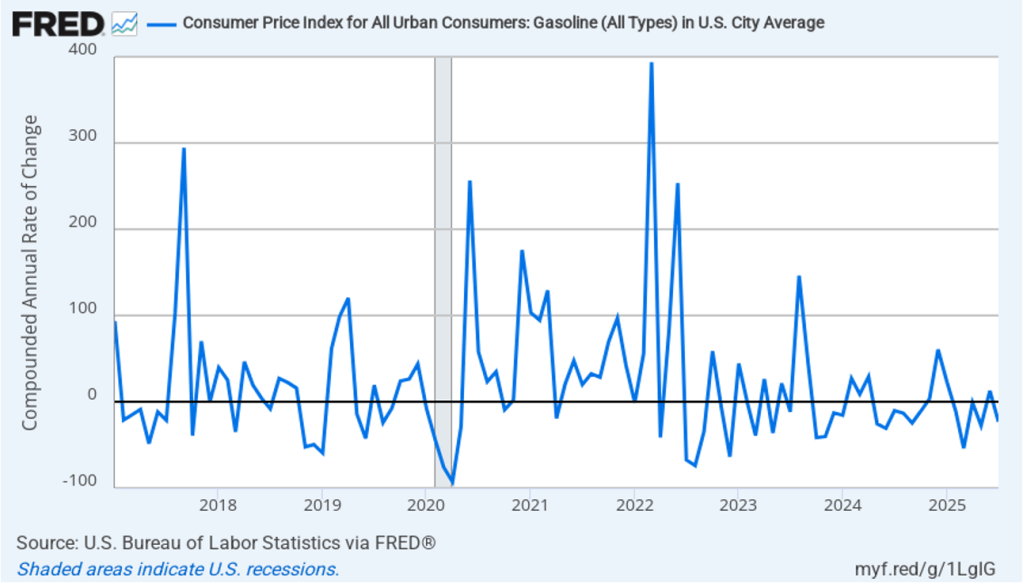

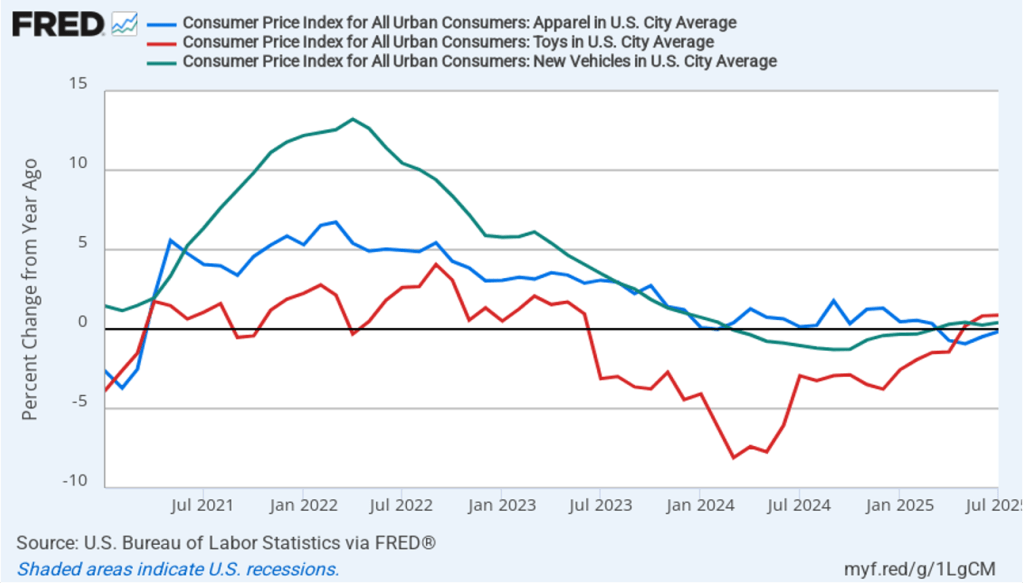

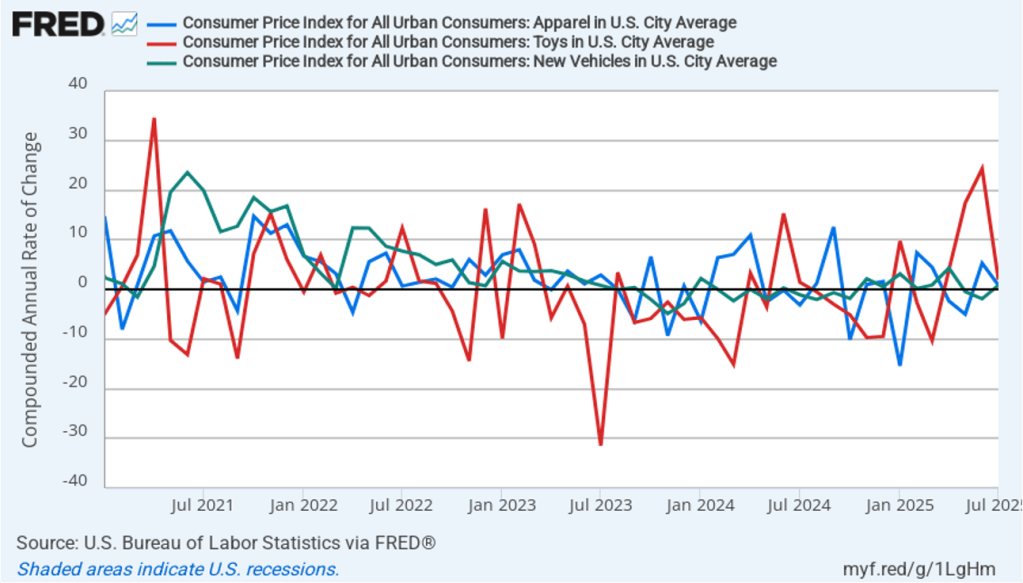

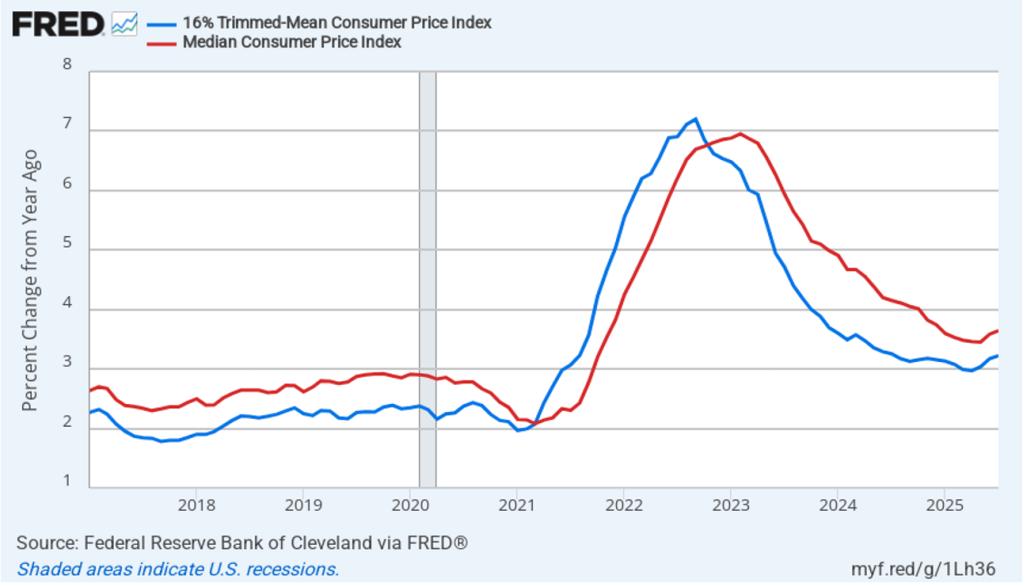

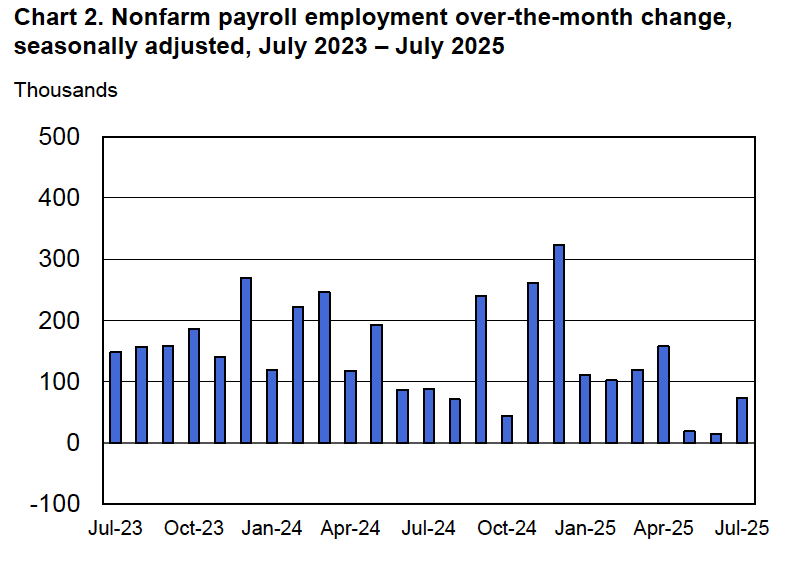

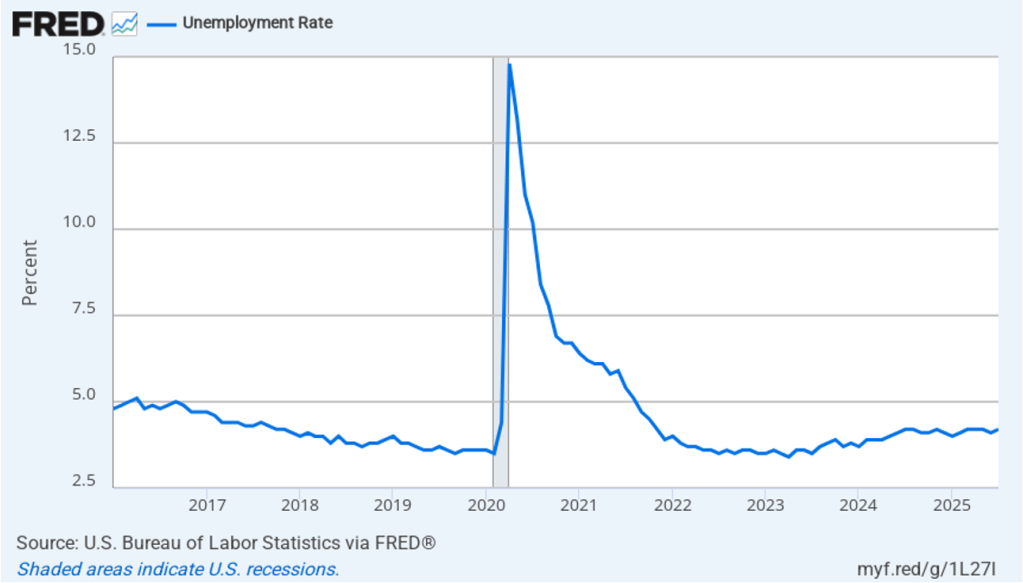

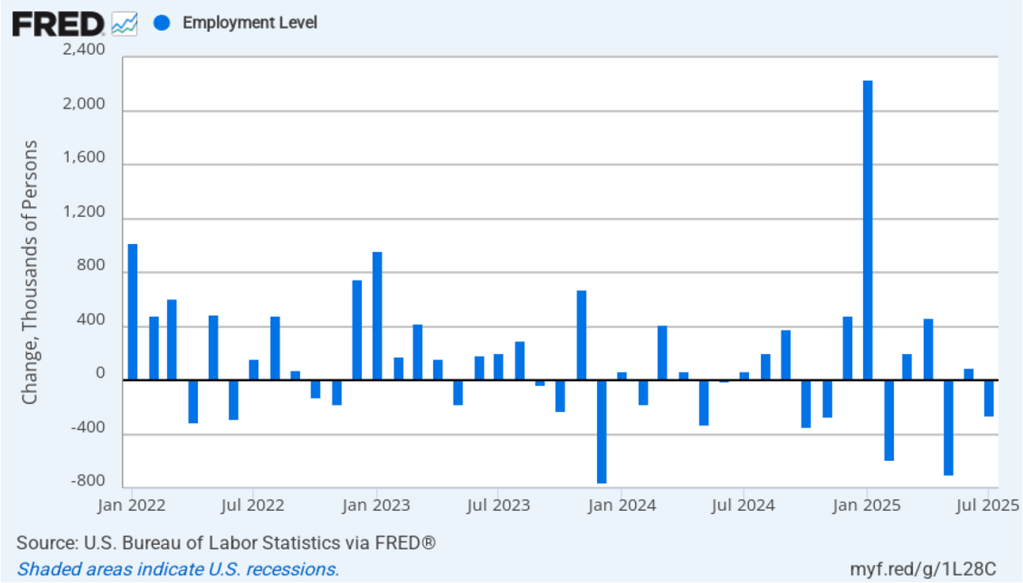

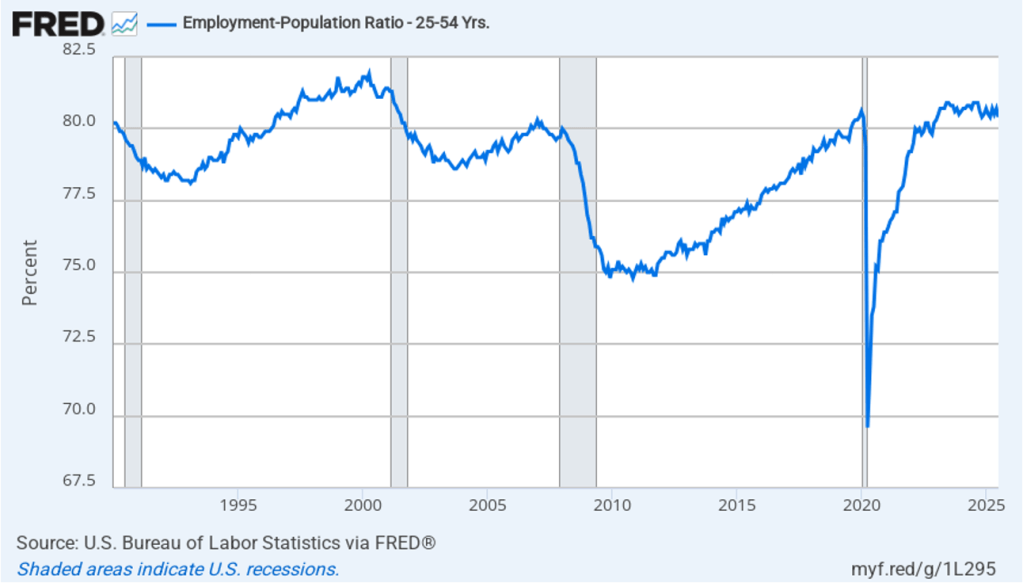

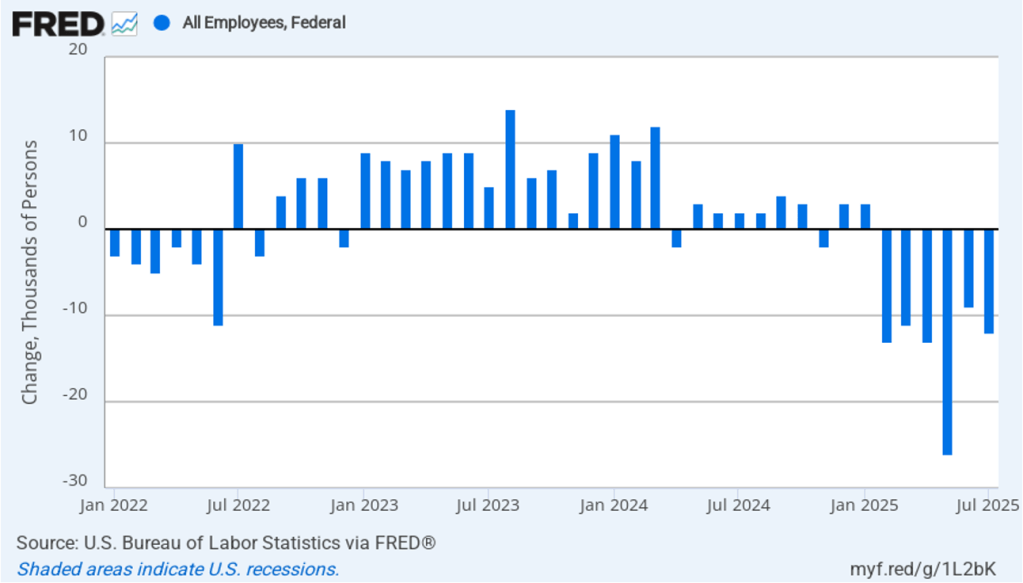

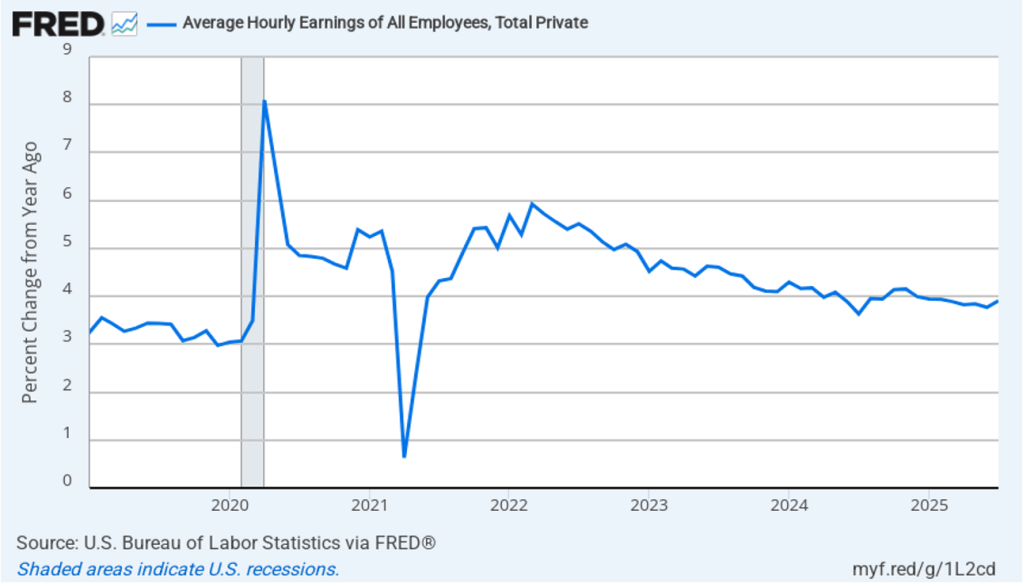

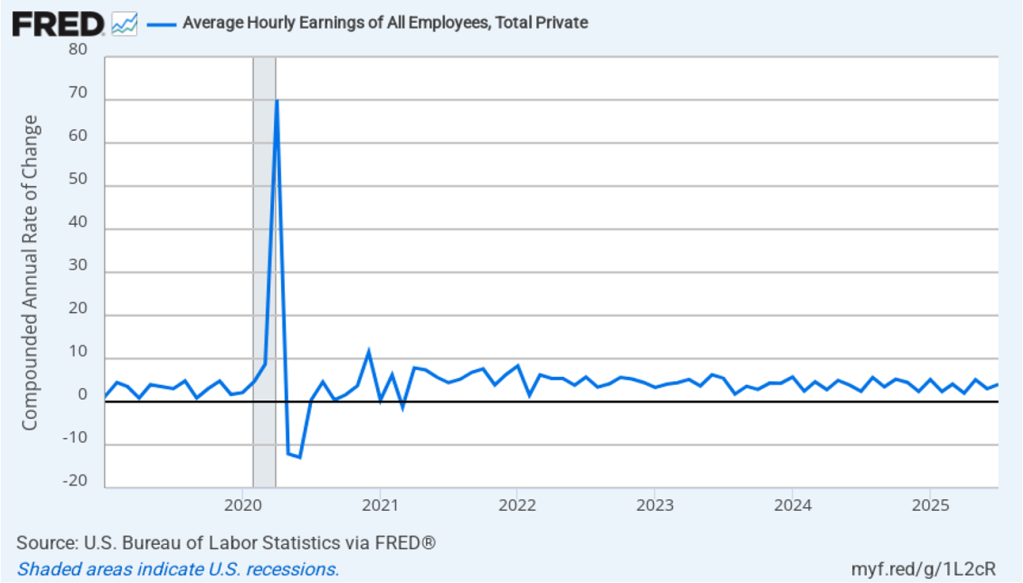

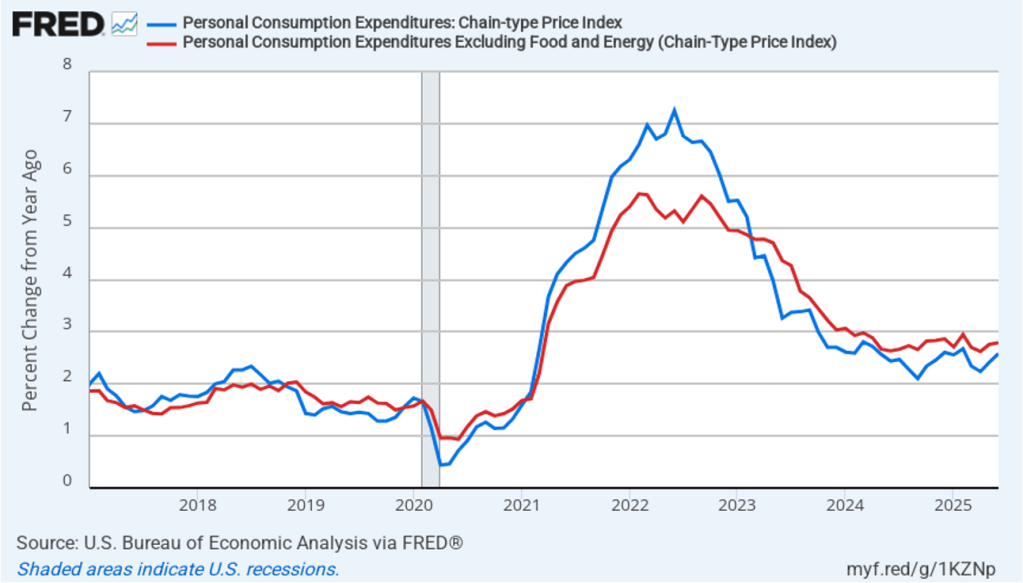

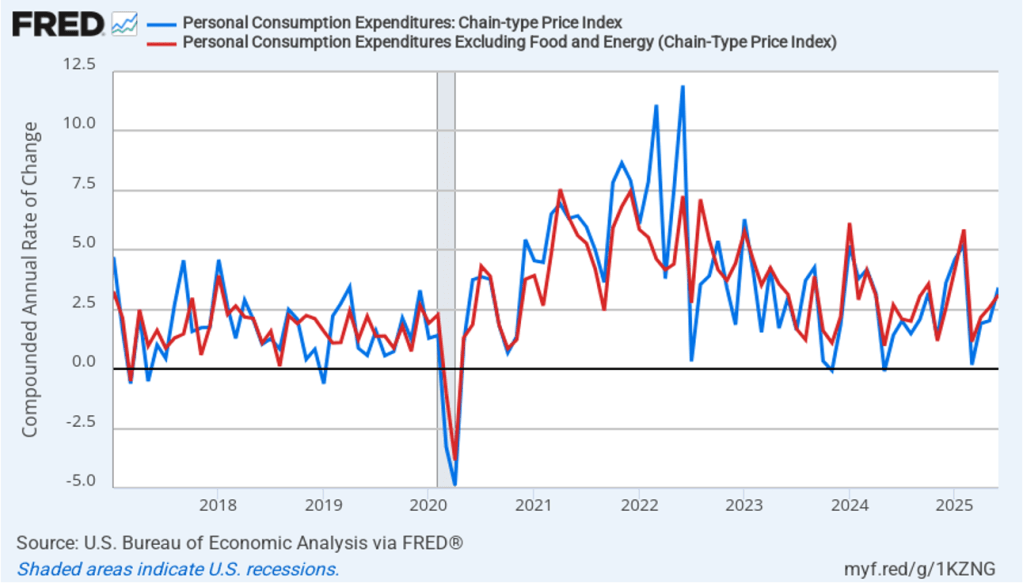

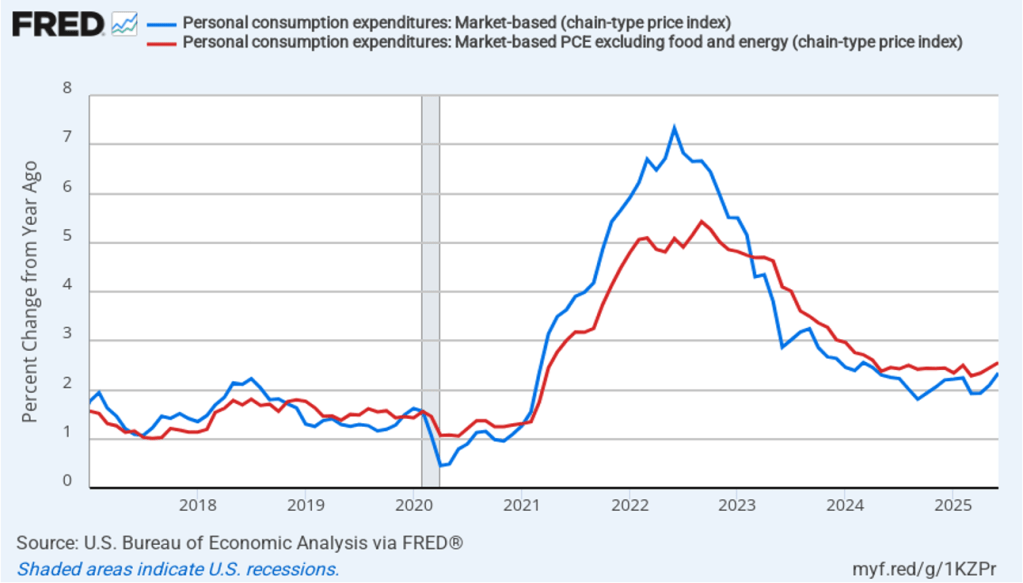

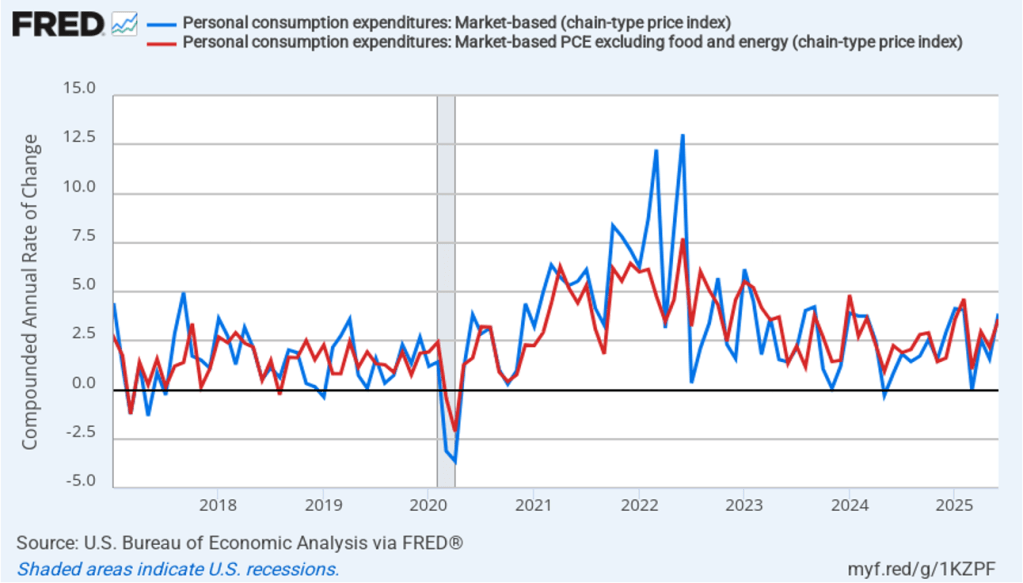

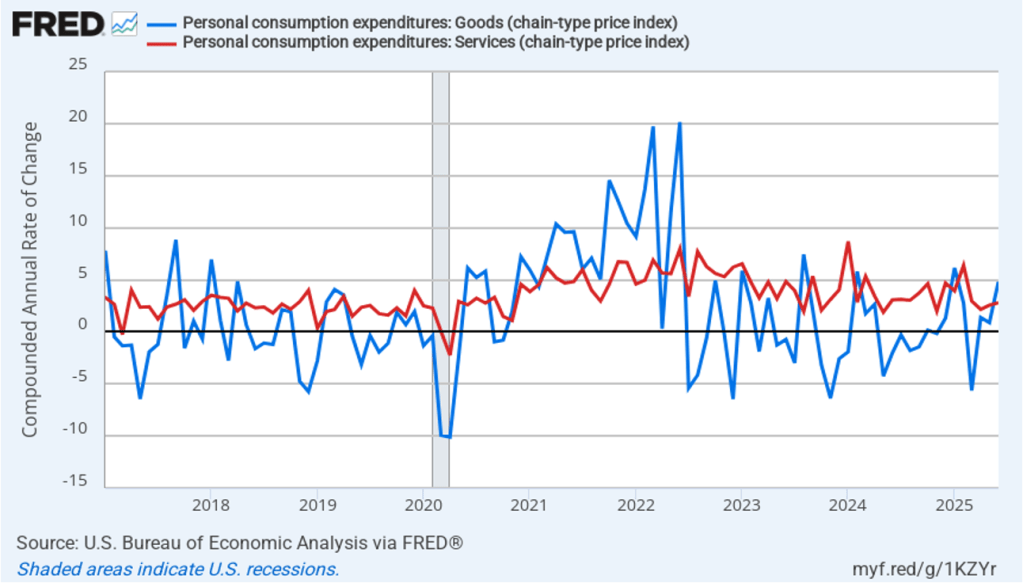

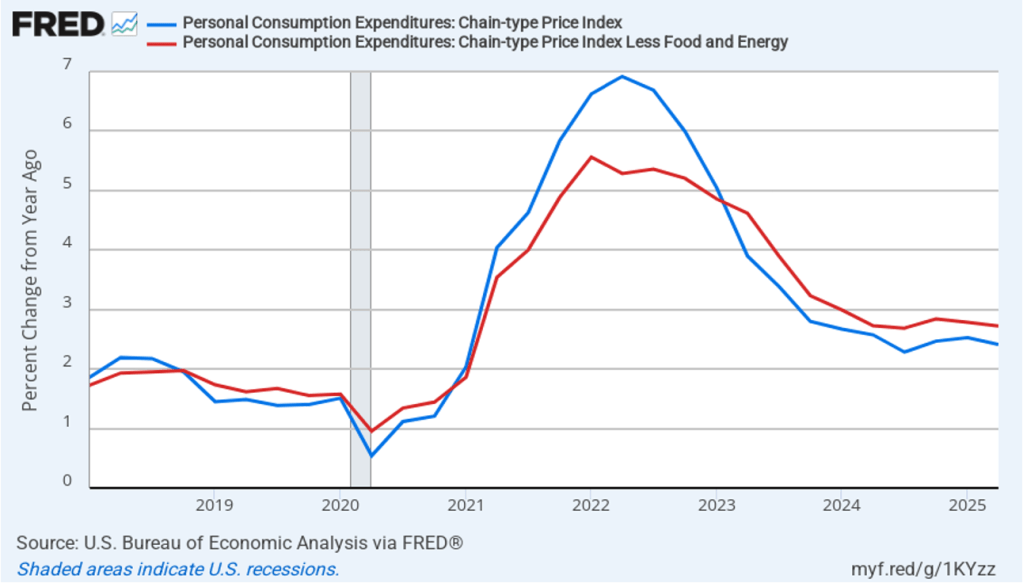

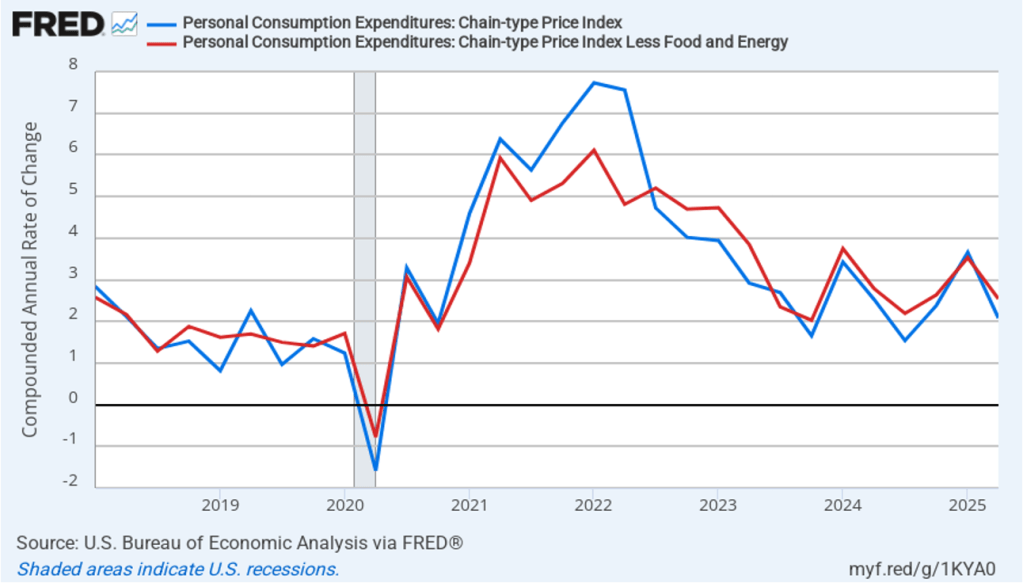

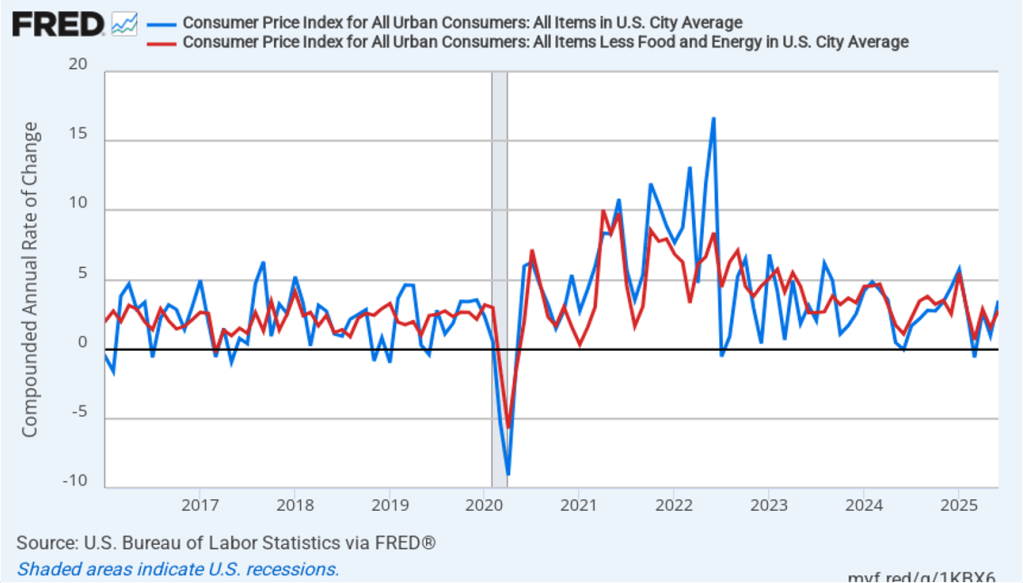

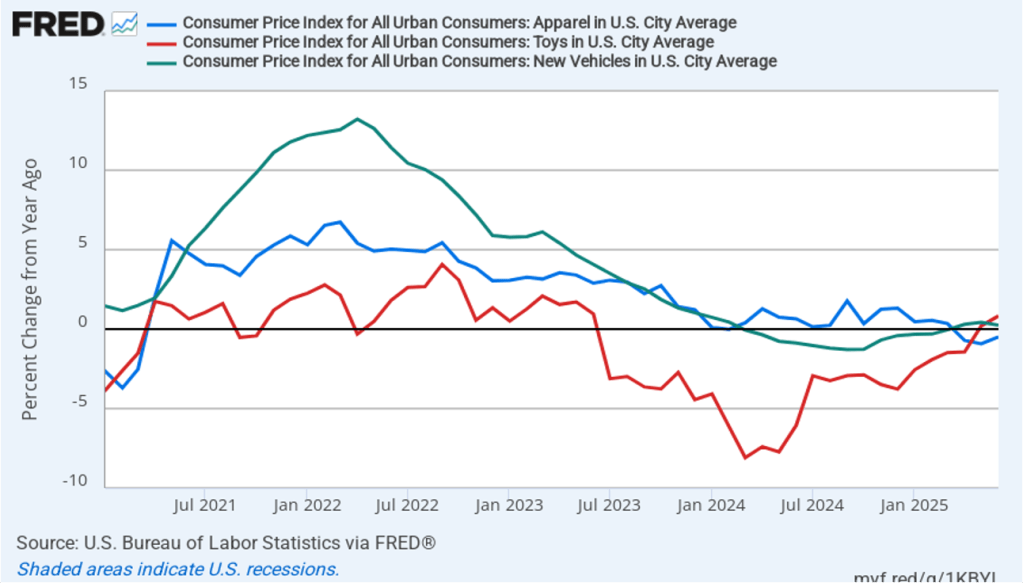

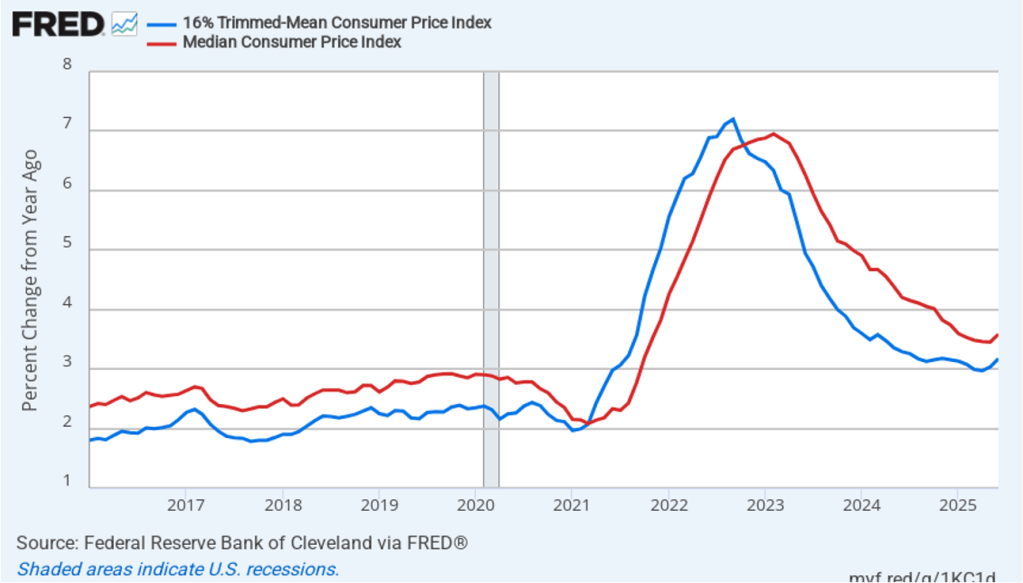

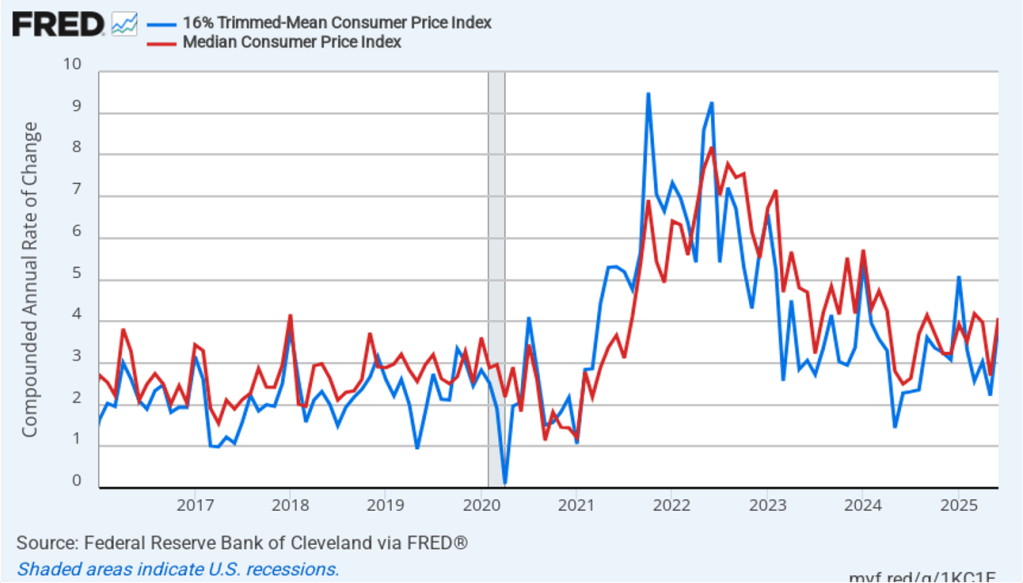

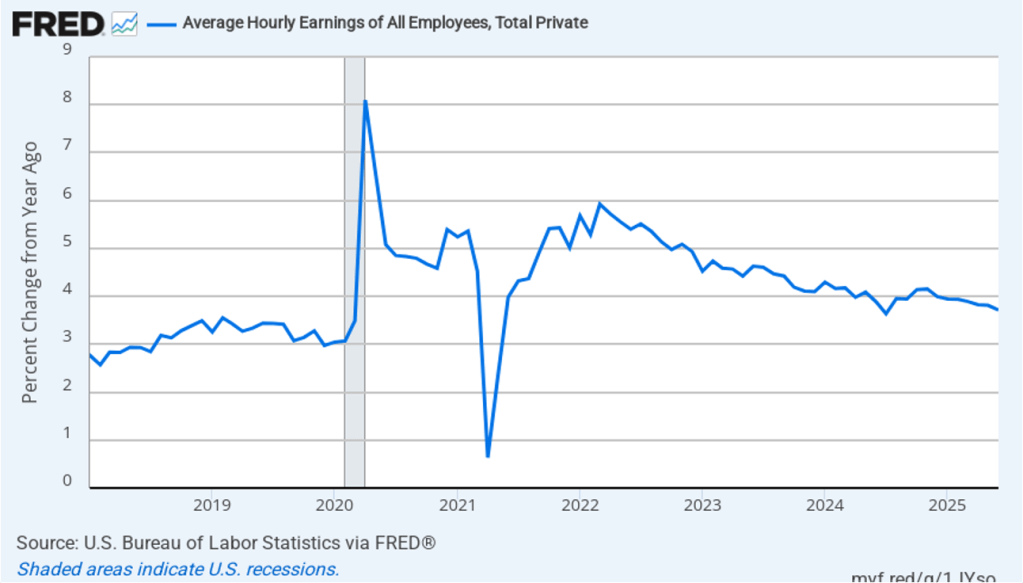

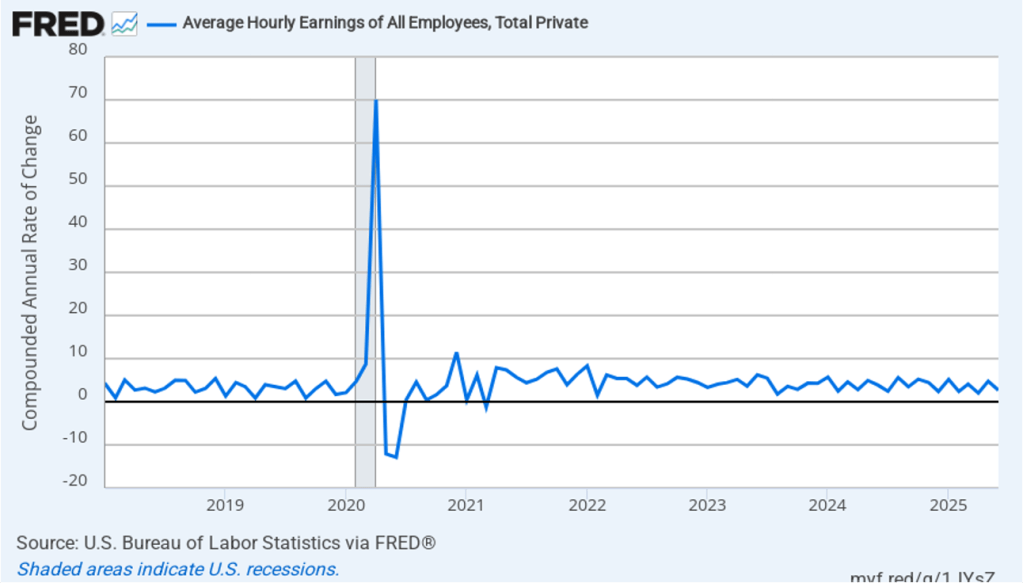

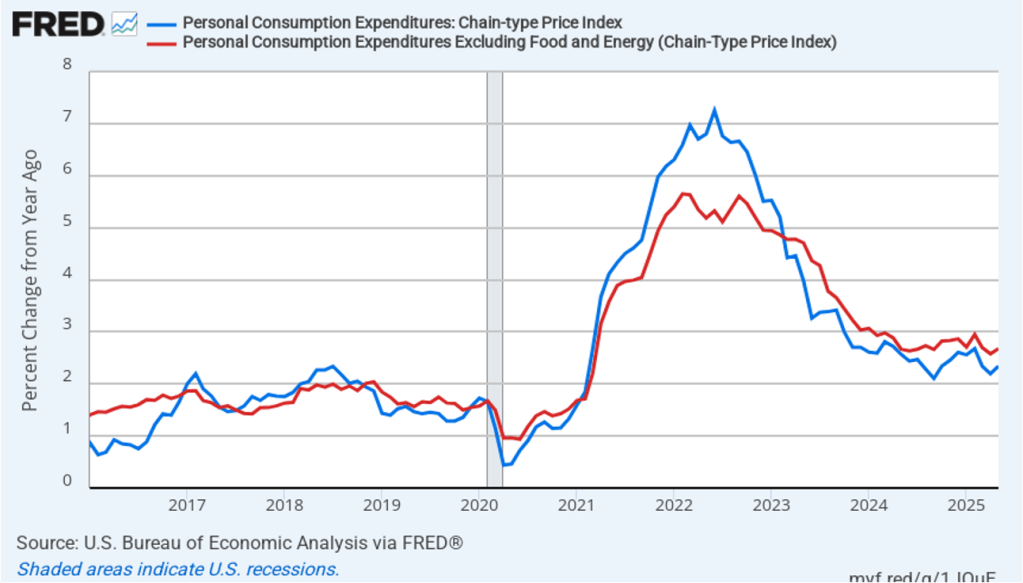

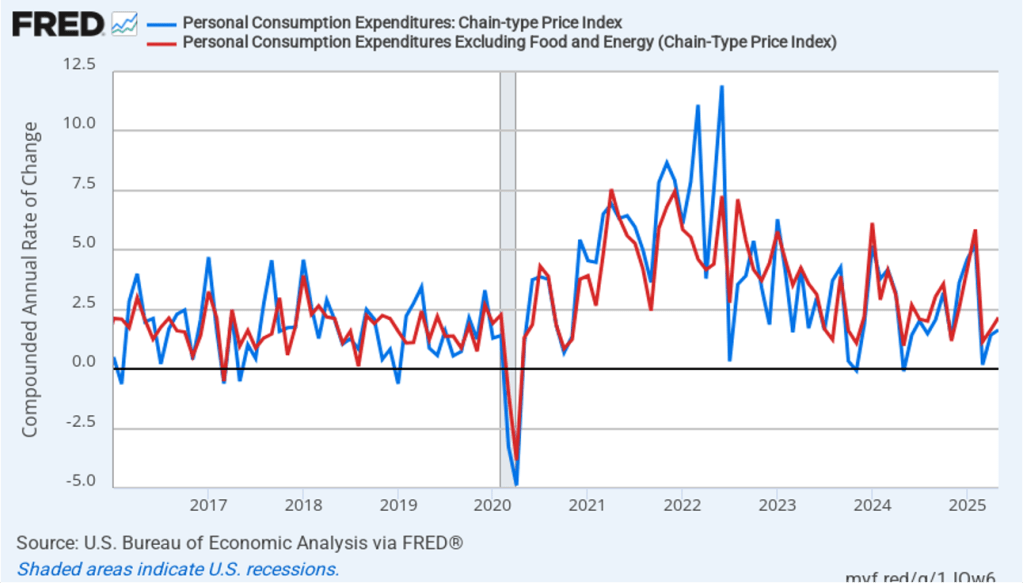

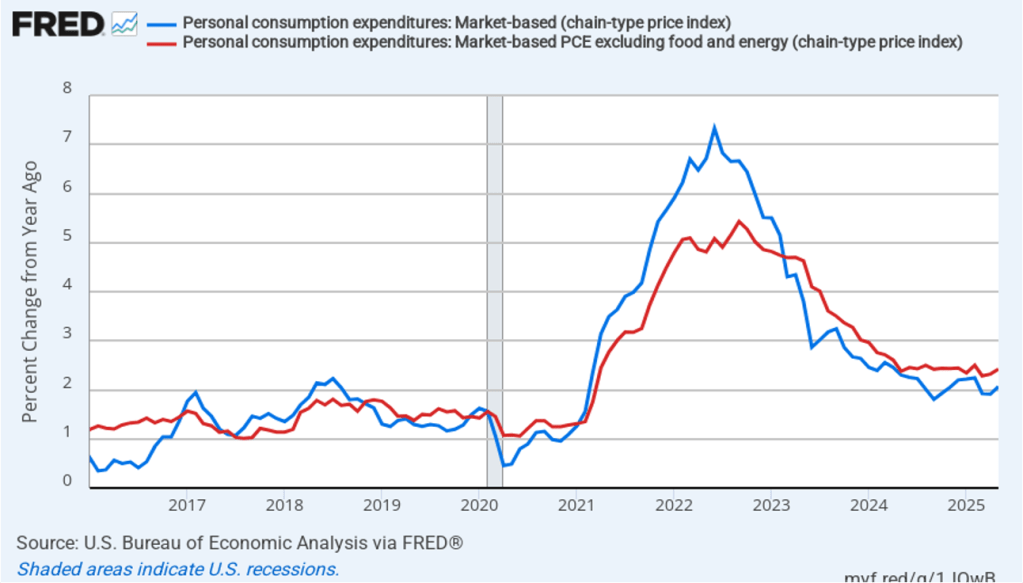

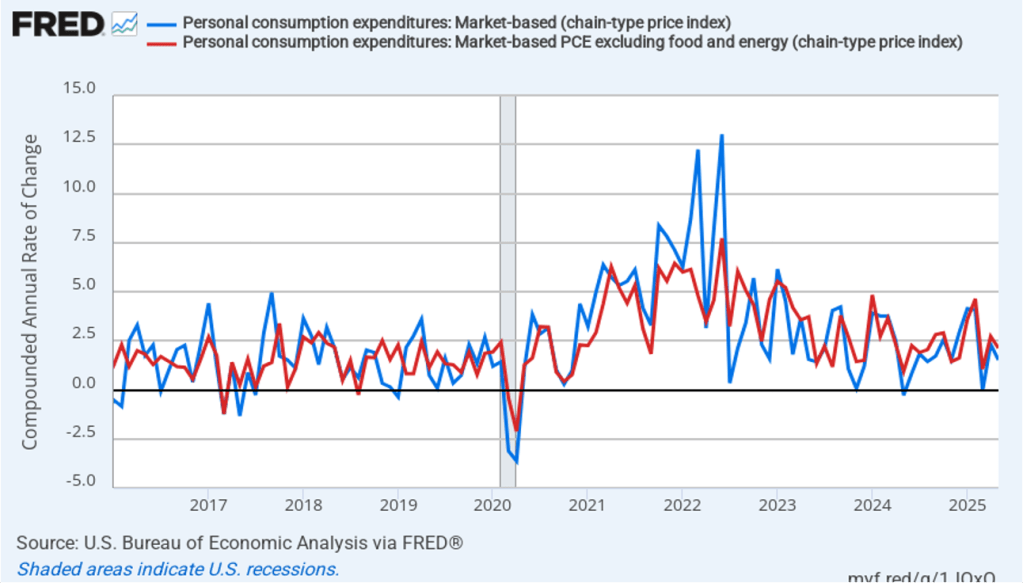

Three issues are particularly important. The first is the Fed’s dual mandate: to ensure stable prices and maximum employment. Many economists (including me) have been critical of the Fed for exhibiting an inflationary bias in 2021 and 2022. The highest inflation rate in 40 years raised pressing questions about whether the Fed has assigned the right weights to inflation and employment.

Clearly, the strategy of pursuing a flexible average inflation target (implying that inflation can be permitted to rise above 2% if it had previously been below 2%) has not been successful. What new approach should the Fed adopt to hit its inflation target? And how can the Fed be held more accountable to Congress and the public? Should it issue a regular inflation report?

The second issue concerns the size and composition of the Fed’s balance sheet. Since the global financial crisis of 2008, the Fed has had a much larger balance sheet and has evolved toward an “ample reserves model” (implying a perpetually high level of reserves). But how large must the balance sheet be to conduct monetary policy, and how important should long-term Treasury debt and mortgage-backed securities be, relative to the rest of the balance sheet? If such assets are to play a central role, how can the Fed best separate the conduct of monetary policy from that of fiscal policy?

The third issue is financial regulation. What regulatory changes does the Fed believe are needed to avoid the kind of costly stresses in the Treasury market we have witnessed in recent years? How can bank supervision be improved? Given that regulation is an inherently political subject, how can the Fed best separate these activities from its monetary policymaking (where independence is critical)?

Addressing these policy questions requires a rethink of process, too. The Fed would be more effective in dealing with a changing economic environment if it acknowledged and debated more diverse viewpoints about the roles of monetary policy and financial regulation in how the economy works.

The Fed’s inflation mistakes, overconfidence in financial regulation, and other errors partly reflect the “groupthink” to which all organizations are prone. Regional Fed presidents’ views traditionally have reflected their own backgrounds and local conditions, but that doesn’t translate easily into a diversity of economic views. Instead of choosing Fed officials based on how they are likely to vote at the next rate-setting meeting, Trump should put more weight on intellectual and experiential diversity. Equally, the Fed itself could more actively seek and listen to dissenting views from academic and business leaders.

Raising questions about policy and process offers guidance about the characteristics that the next Fed chair will need to succeed. These obviously include knowledge of monetary policy and financial regulation and mature, independent judgment; but they also include diverse leadership experience and an openness to new ideas and perspectives that might enhance the institution’s performance and accountability. One hopes that Trump’s selection of the next Fed chair, and the Senate’s confirmation process, will emphasize these attributes.