Image generated by ChatGTP-4o of a family shopping in a supermarket.

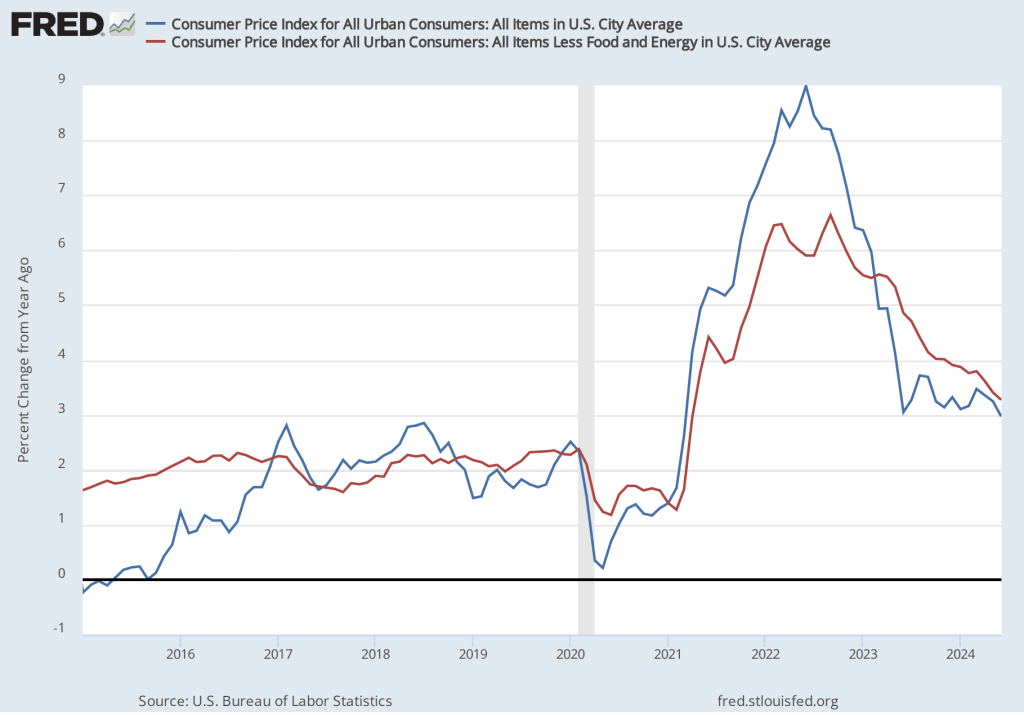

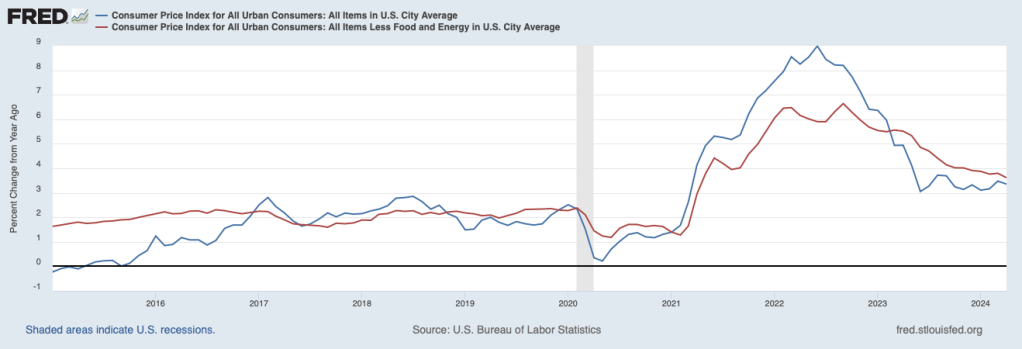

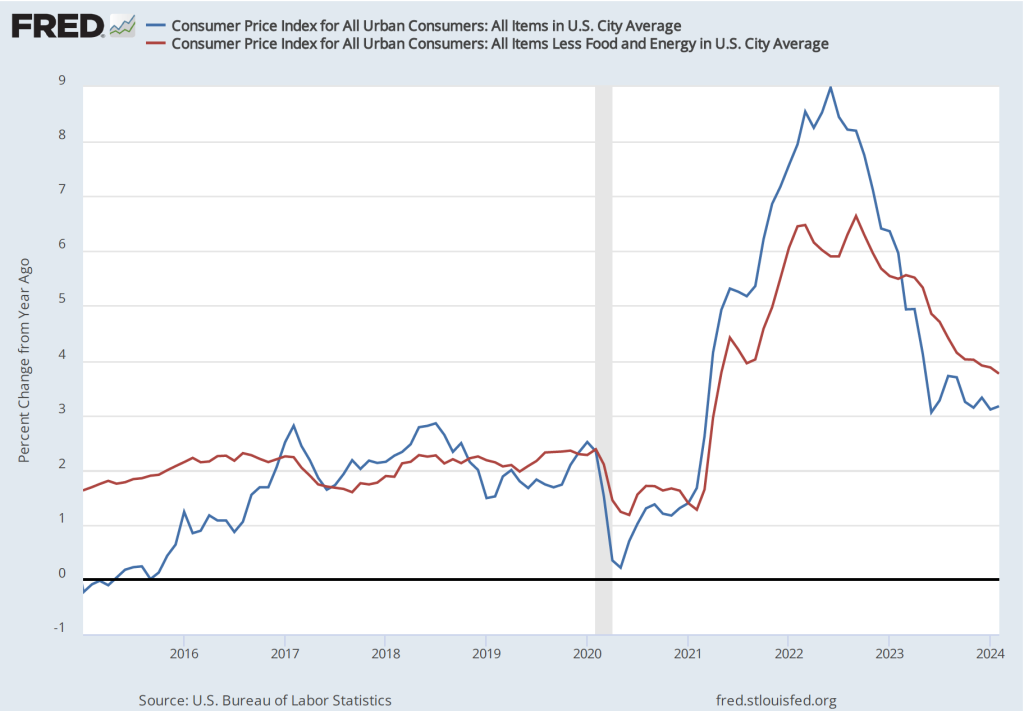

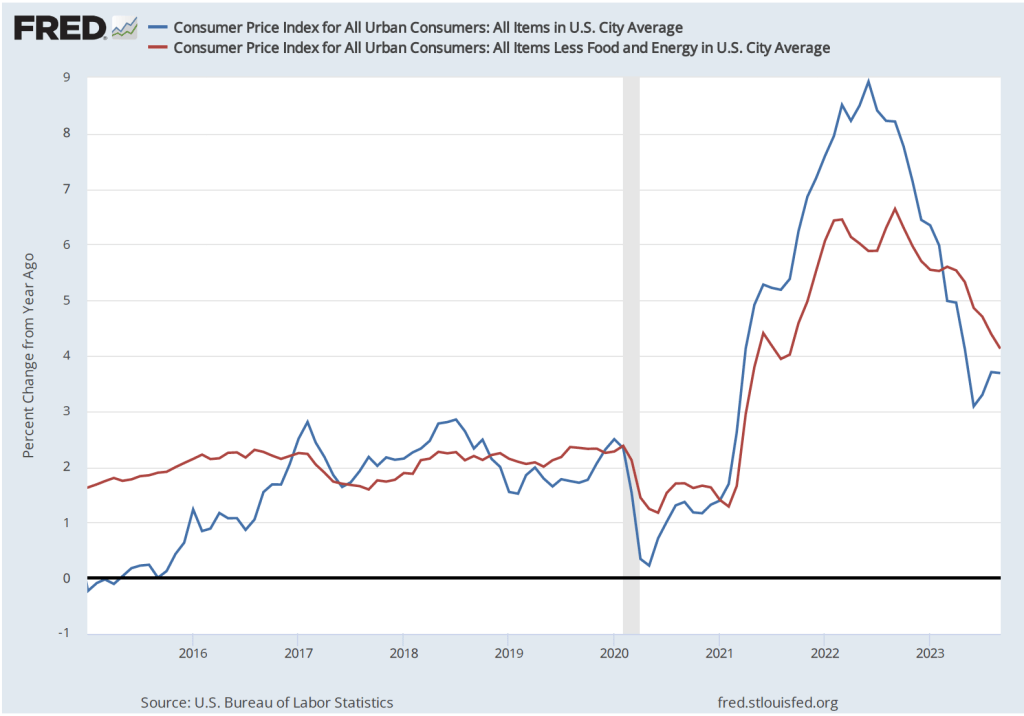

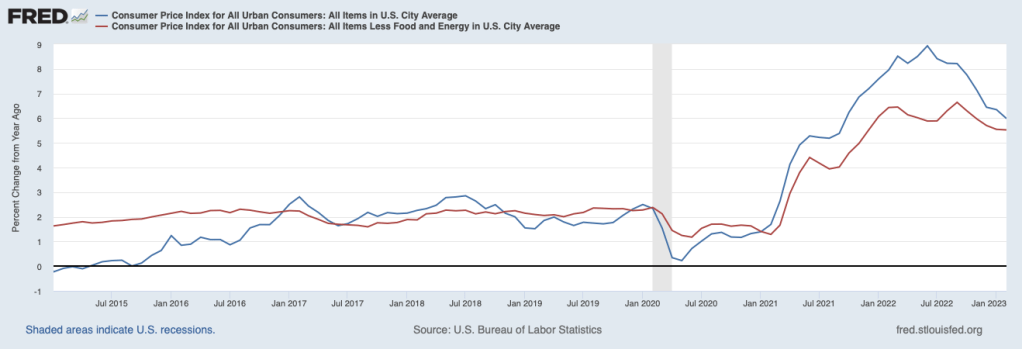

Today (May 13), the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released its report on the consumer price index (CPI) for April. The following figure compares headline inflation (the blue line) and core inflation (the green line).

- The headline inflation rate, which is measured by the percentage change in the CPI from the same month in the previous year, was 2.3 percent in April—down from 2.4 percent in March.

- The core inflation rate, which excludes the prices of food and energy, was 2.8 percent in April—unchanged from March.

Headline inflation was the lowest since February in 2021—before the acceleration in inflation that began in the spring of 2021. Core inflation was the lowest since March 2021. Both headline inflation and core inflation were what economists surveyed had expected.

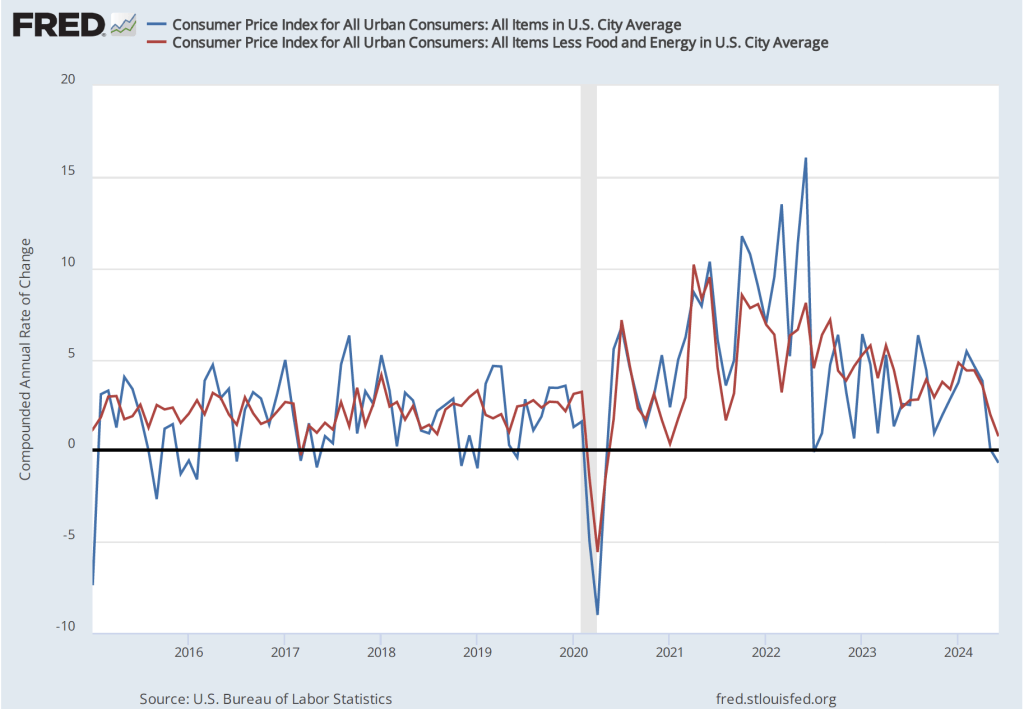

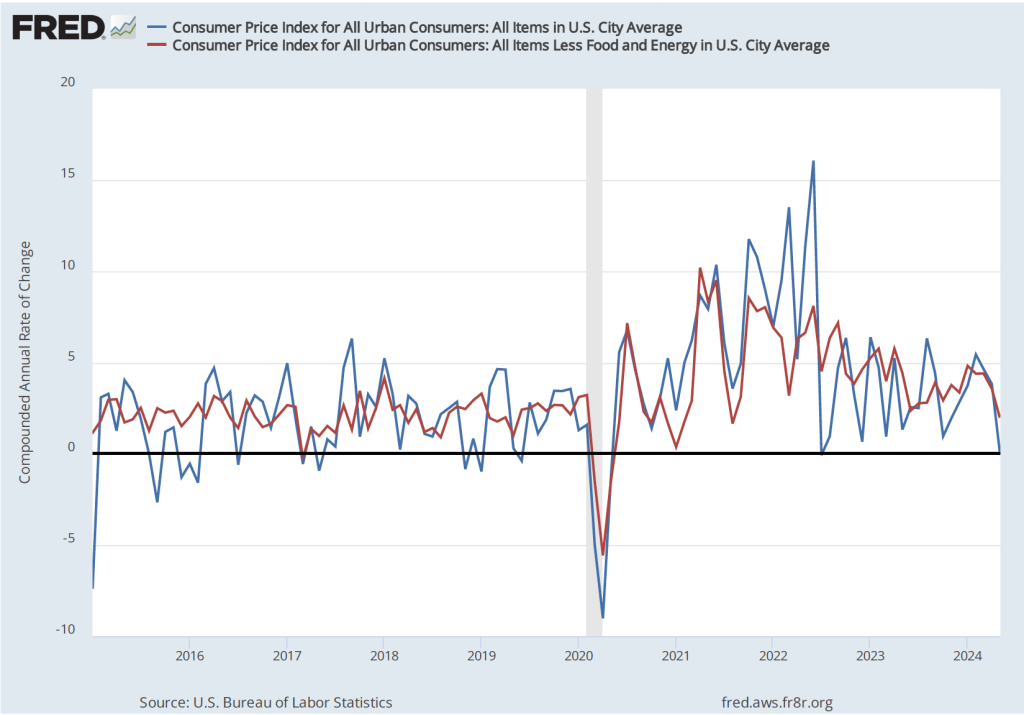

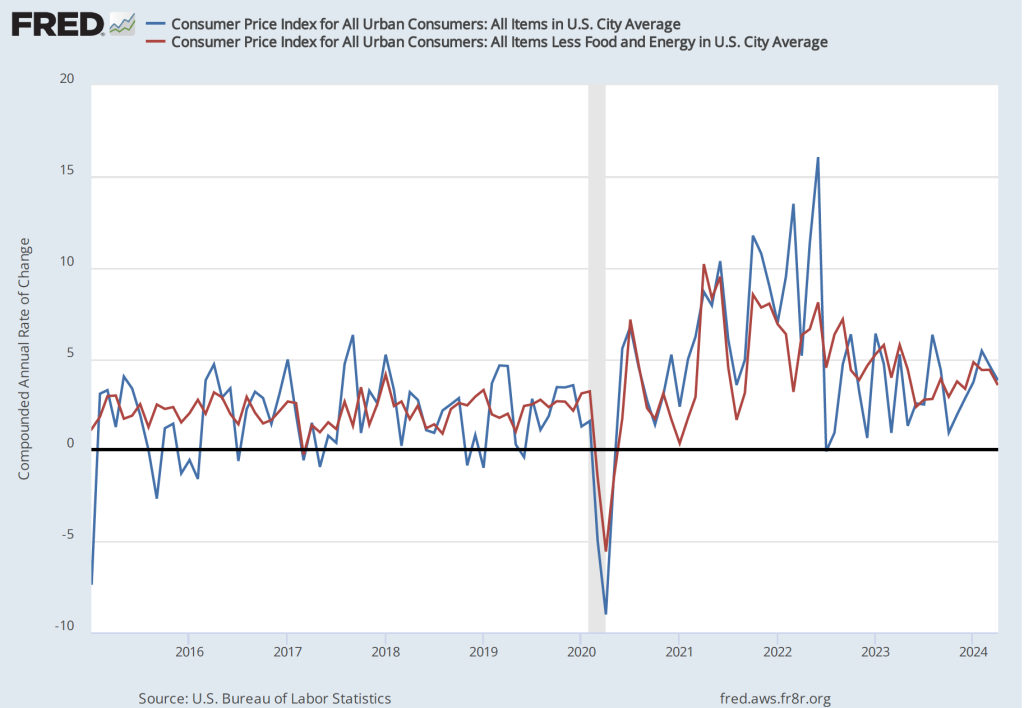

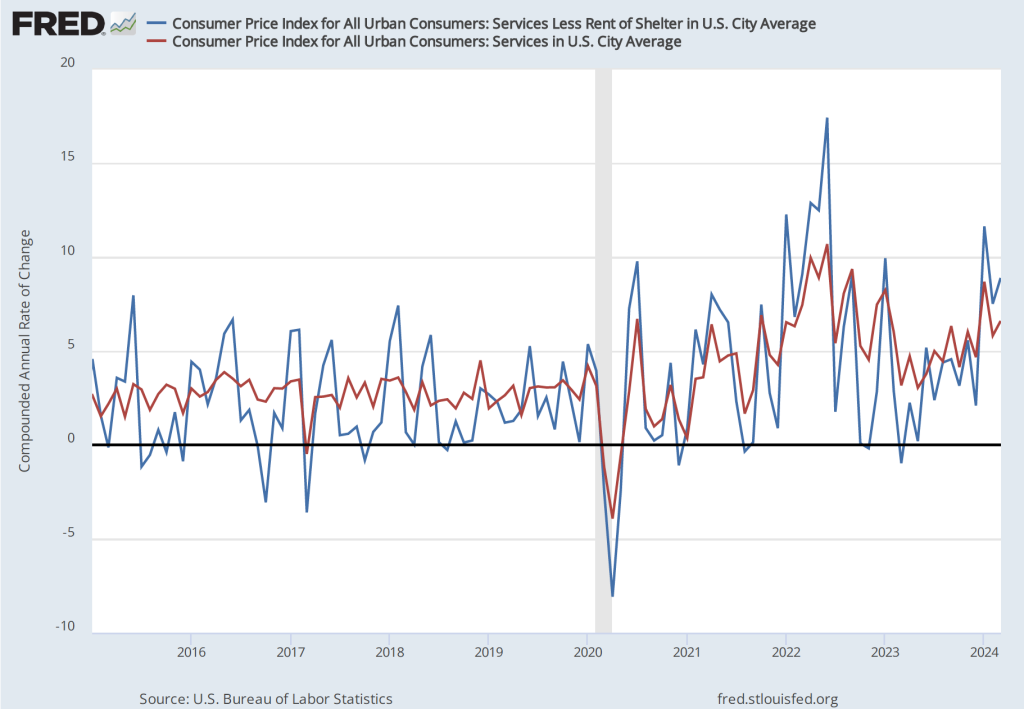

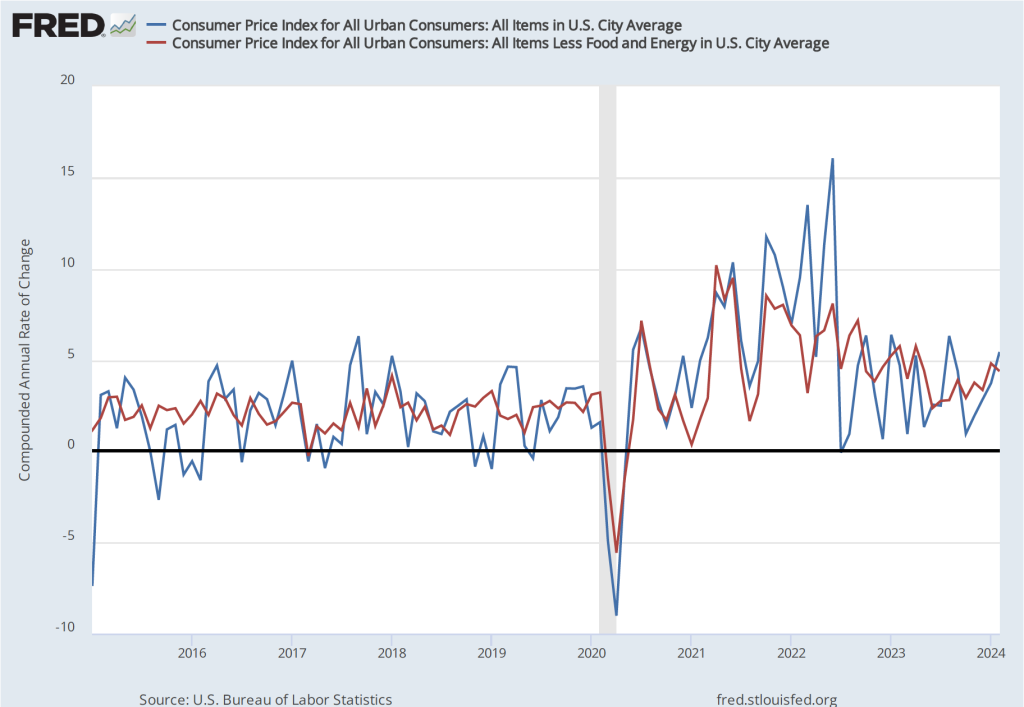

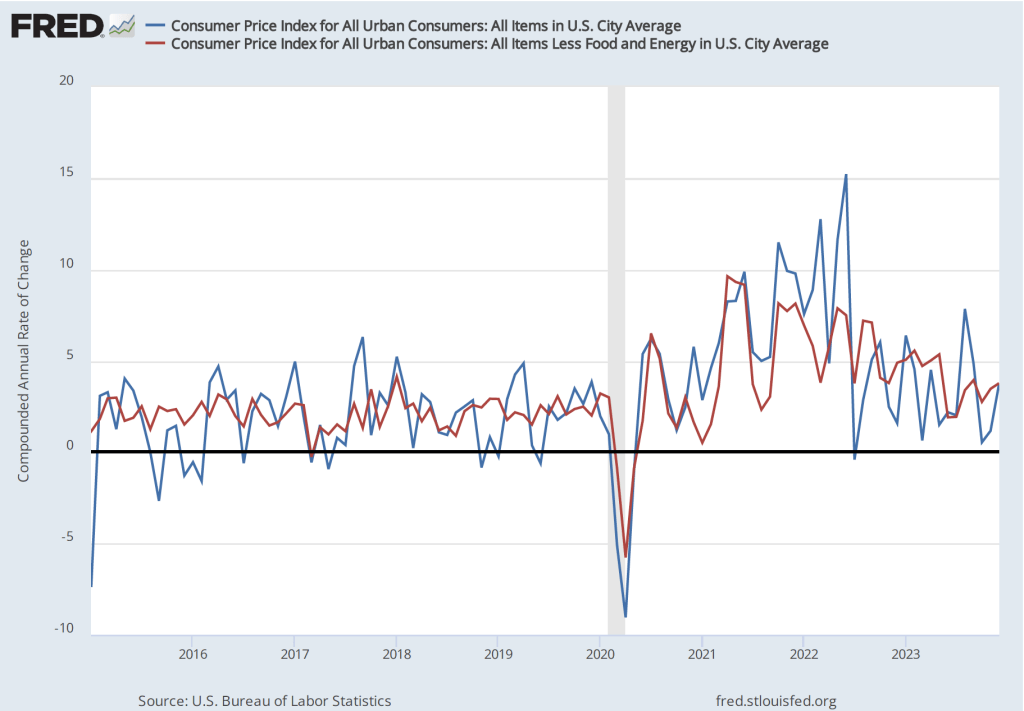

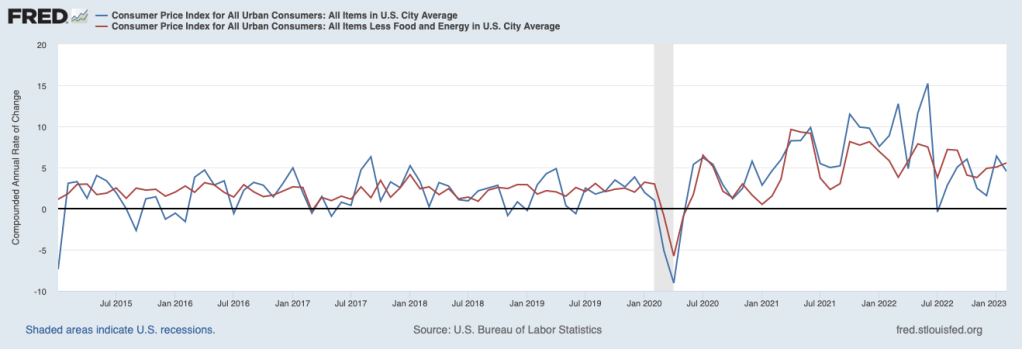

In the following figure, we look at the 1-month inflation rate for headline and core inflation—that is the annual inflation rate calculated by compounding the current month’s rate over an entire year. Calculated as the 1-month inflation rate, headline inflation (the blue line) rose from –0.6 percent in March to 2.7 percent in April. Core inflation (the red line) rose from 0.9 percent in March to 2.9 percent in April.

The 1-month and 12-month inflation rates are telling different stories, with 12-month inflation indicating that the rate of price increase is back to what it was in early 2021. The 1-month inflation rate indicates a significant increase in April from the very low rate of price increase in March. The 1-month inflation rate indicates that inflation is still running ahead of the Fed’s 2 percent annual inflation target.

Of course, it’s important not to overinterpret the data from a single month. The figure shows that 1-month inflation is particularly volatile. It is possible, though, that the increase in 1-month inflation in April reflects the effect on the price level of the large tariff increases the Trump Administration announced on April 2. Whether those effects will persist is unclear because the administration has been engaged in negotiations that may significantly reduce the tariff increases announced in April. Finally, note that the Fed uses the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index, rather than the CPI, to evaluate whether it is hitting its 2 percent annual inflation target.

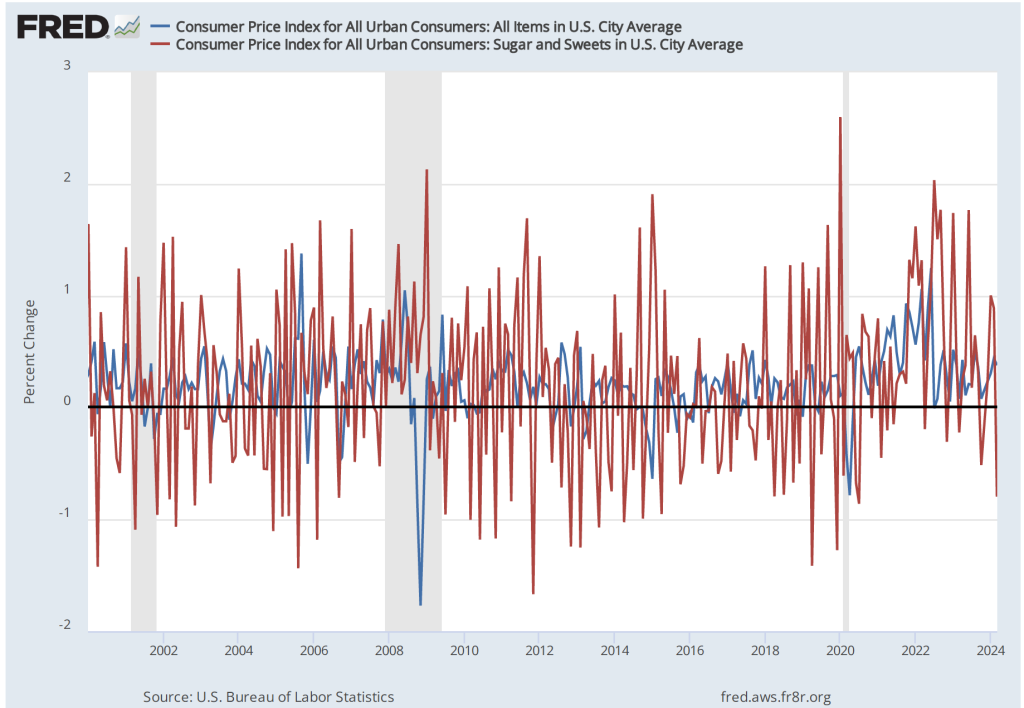

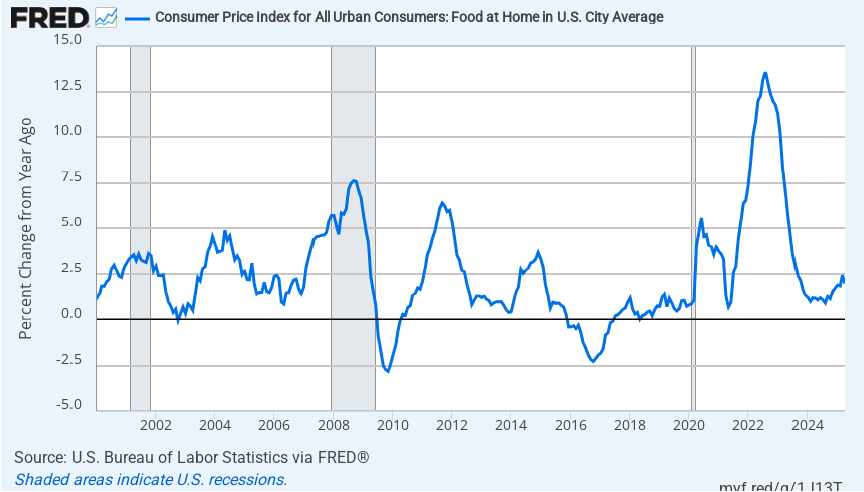

There’s been considerable discussion in the media about continuing inflation in grocery prices. The following figure shows inflation in the CPI category “food at home,” which is primarily grocery prices. Inflation in grocery prices was 2.0 percent in April and has been below 2.5 percent every month since September 2023. Over the past year, there has been a slight upward trend in inflation in grocery prices but to this point it remains relatively low, although well above the very low rates of inflation in grocery prices that prevailed from 2015 to 2019.

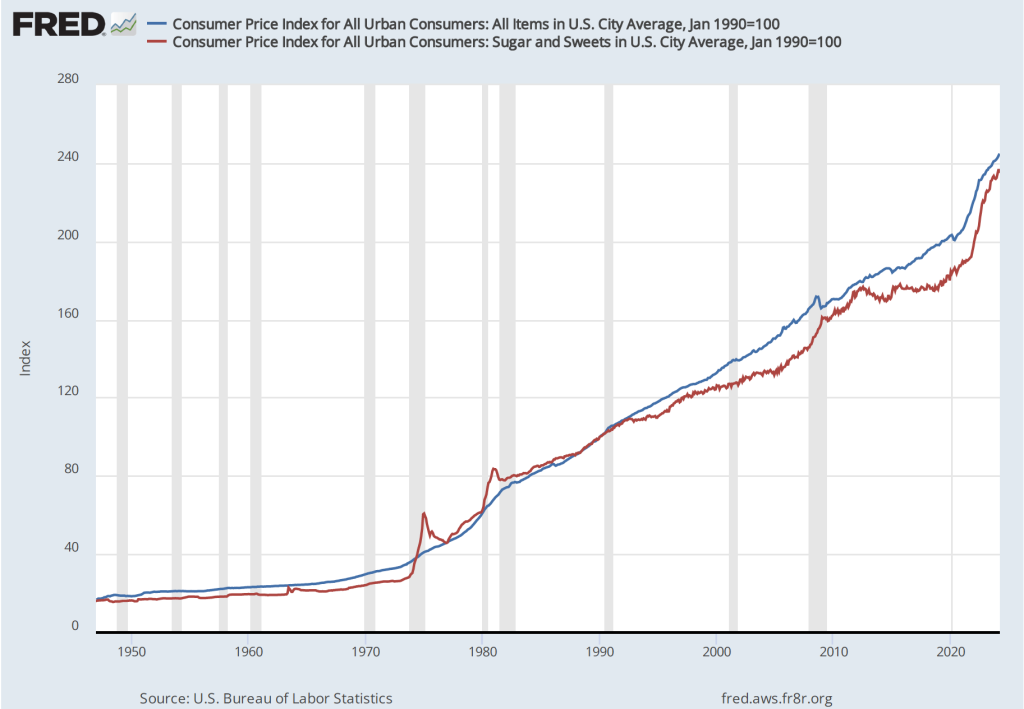

It’s the nature of the CPI that in any given month some prices will increase rapidly while other prices will increase slowly or even decline. Although, on average, grocery price inflation has been relatively low, there have been substantial increases in the prices of some food items. For instance, a recent article in the Wall Street Journal noted that rising cattle prices will likely be reflected in coming months rising prices for beef purchased in supermarkets. The following figure shows inflation in the prices of ground beef and steaks over the period starting in January 2015. As we should expect, the prices of these two goods are more volatile mont to month than are grocery prices as a whole. Ground beef prices increased 10.8 percent in April, an increase that will likely be noticeable to someone planning for a Memorial Day cookout.

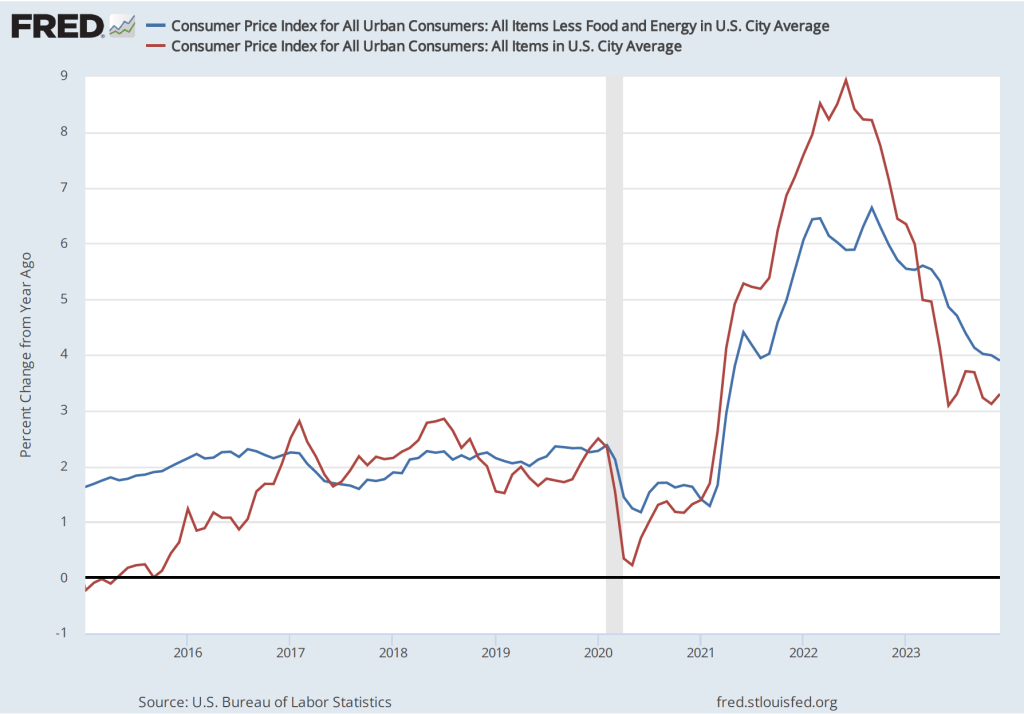

To better estimate the underlying trend in inflation, some economists look at median inflation and trimmed mean inflation.

- Median inflation is calculated by economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland and Ohio State University. If we listed the inflation rate in each individual good or service in the CPI, median inflation is the inflation rate of the good or service that is in the middle of the list—that is, the inflation rate in the price of the good or service that has an equal number of higher and lower inflation rates.

- Trimmed-mean inflation drops the 8 percent of goods and services with the highest inflation rates and the 8 percent of goods and services with the lowest inflation rates.

The following figure shows that 12-month trimmed-mean inflation (the blue line) was 3.0 percent in April, unchanged from March. Twelve-month median inflation (the red line) 3.5 percent in April, also unchanged from March.

The following figure shows 1-month trimmed-mean and median inflation. One-month trimmed-mean inflation increased from 2.6 percent in March to 3.0. percent in April. One-month median inflation declined from 4.2 percent in March to 4.0 percent in April. These data, although mixed, provide some confirmation that inflation likely increased somewhat from March to April.

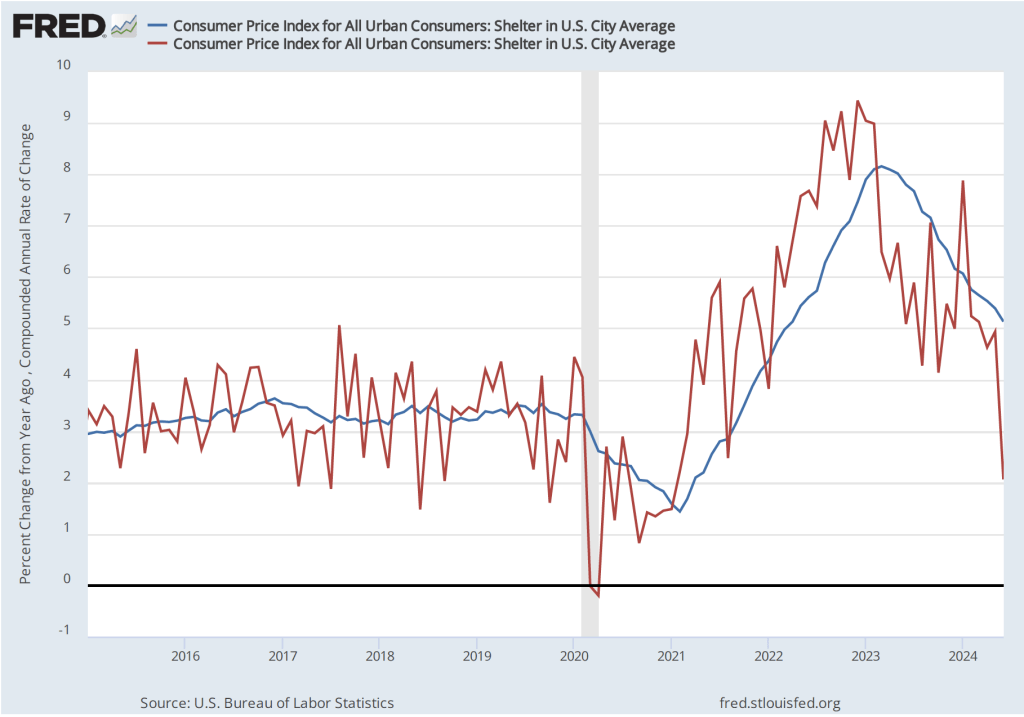

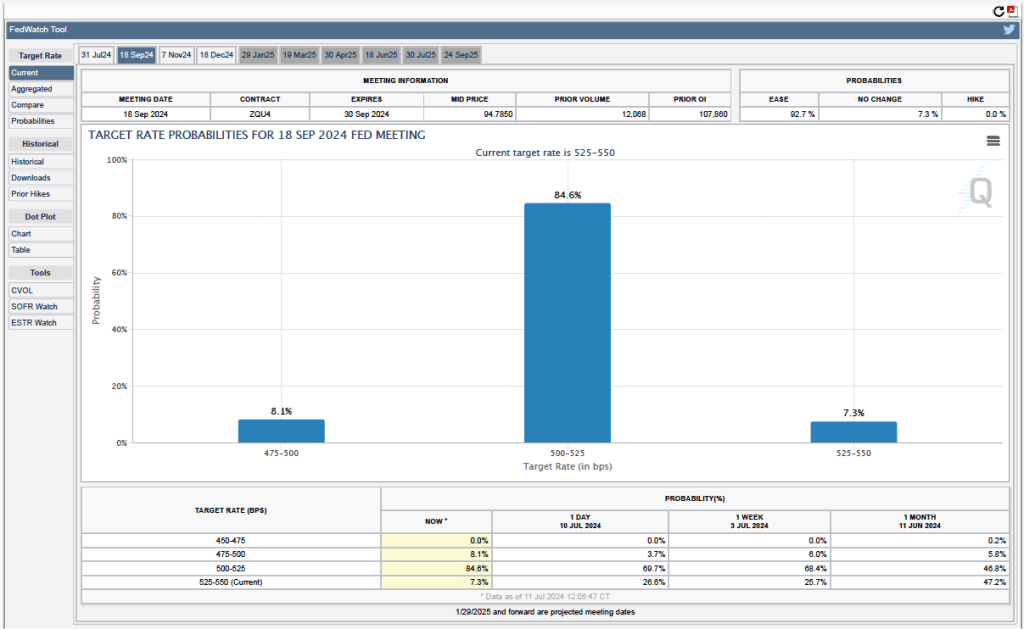

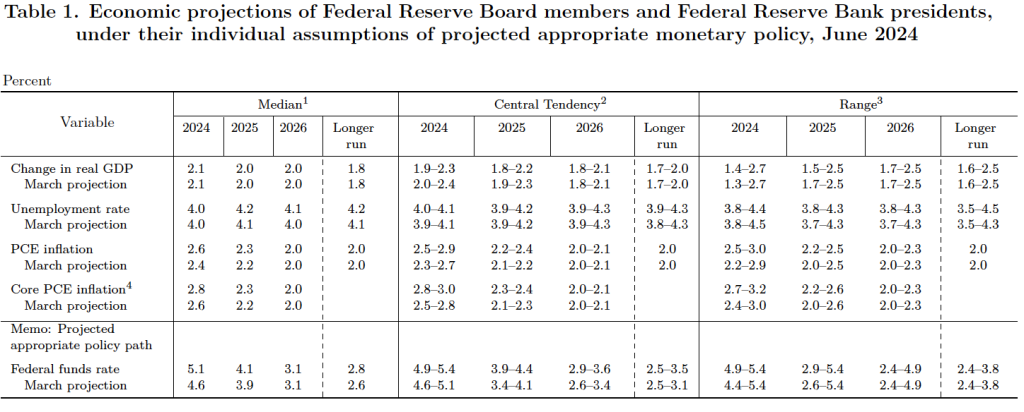

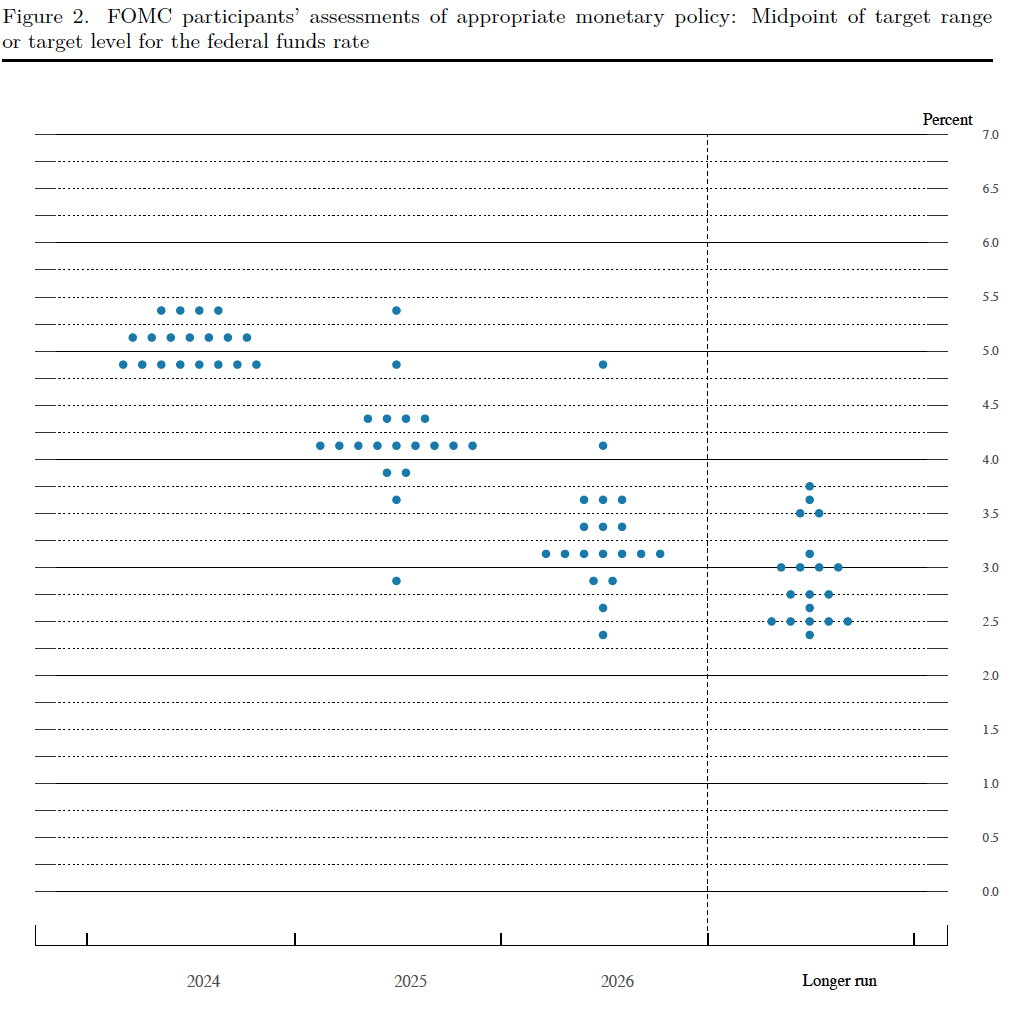

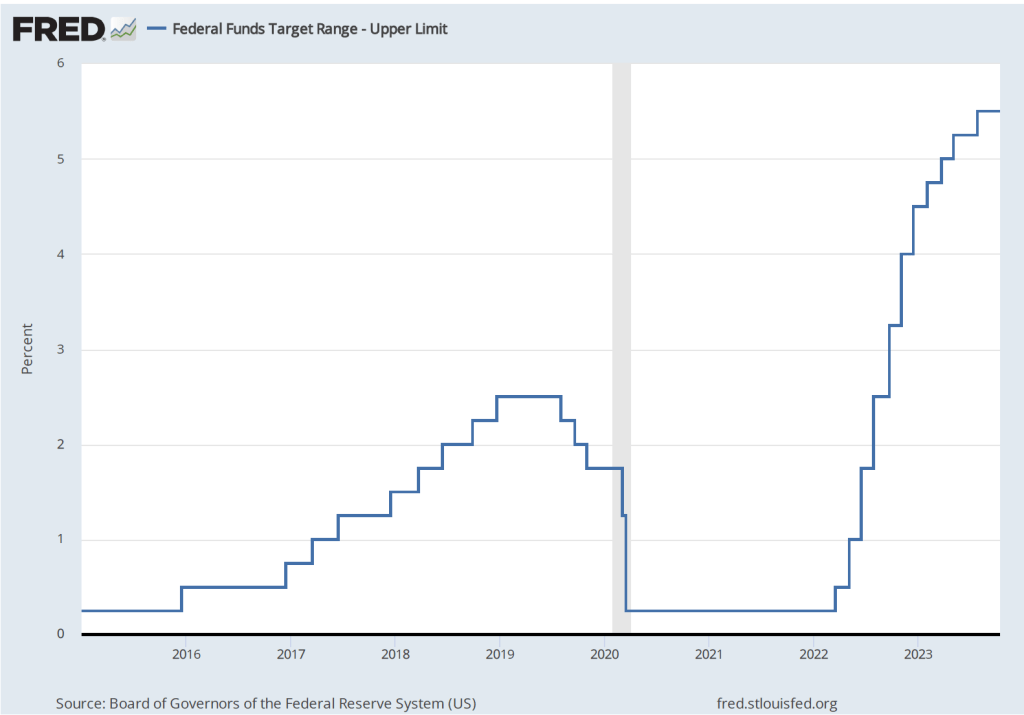

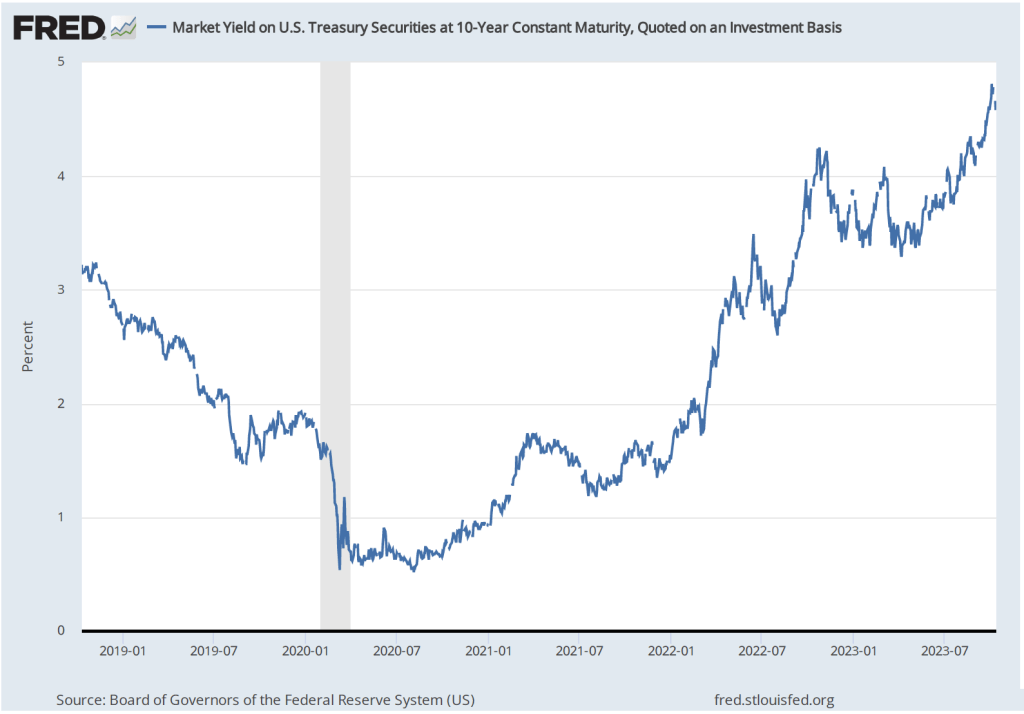

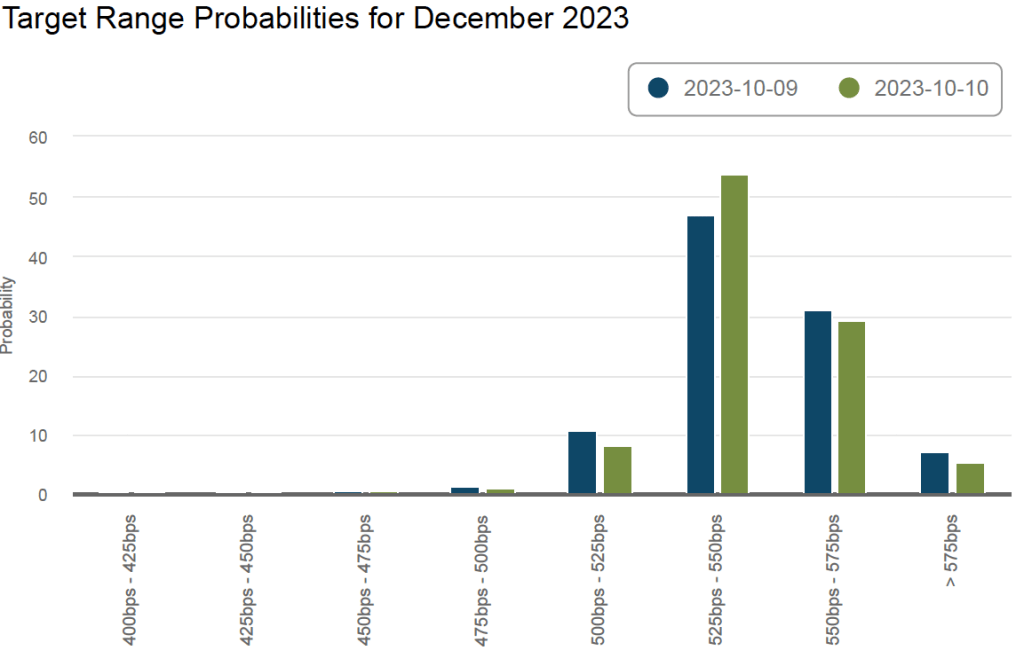

What are the implications of this CPI report for the actions the FOMC may take at its next several meetings? Investors who buy and sell federal funds futures contracts still do not expect that the FOMC will cut its target for the federal funds rate at its next two meetings. (We discuss the futures market for federal funds in this blog post.) Today, investors assigned only an 8.4 percent probability to the Fed’s policymaking Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) cutting its target from the current 4.25 percent to 4.50 percent range at its meeting on June 17–18. Investors assigned a probability of 34.9 percent that the FOMC will cut its target after its meeting on July 29–30. Investors assigned a probability of 73.1 percent that the committee will cut its target after its meeting on September 16–17. The FOMC’s actions will likely depend in part on the success of the current trade negotiations.