Photo from Lena Buonanno

This morning the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) released its advance estimate of GDP for the third quarter of 2023. (The report can be found here.) The BEA estimates that real GDP increased by 4.9 percent at an annual rate in the third quarter—July through September. That was more than double the 2.1 percent increase in real GDP in the second quarter, and slightly higher than the 4.7 percent that economists surveyed by the Wall Street Journal last week had expected. The following figure shows the rates of GDP growth each quarter beginning in 2021.

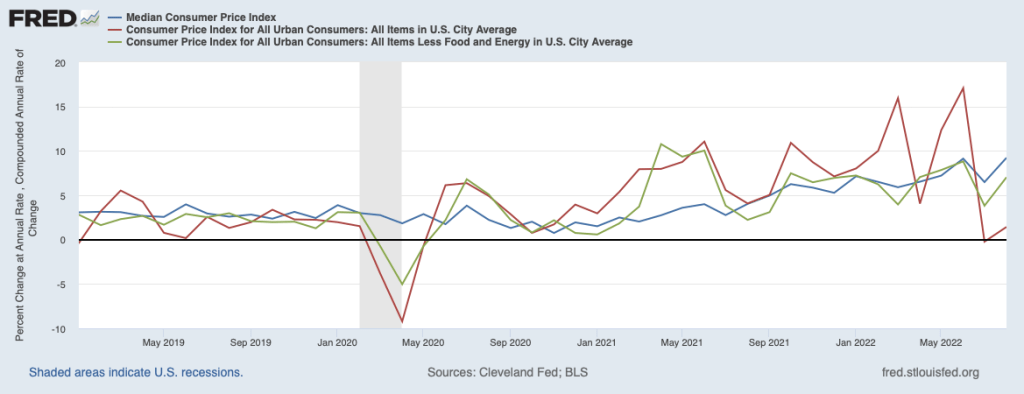

Note that the BEA’s most recent estimates of real GDP during the first two quarters of 2022 still show a decline. The Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee only switched from a strongly expansionary monetary policy, with a target for the federal funds of effectively zero, to a contractionary monetary policy following its March 16, 2022 meeting. That real GDP was declining even before the Fed had pivoted to a contractionary monetary policy helps explain why, despite strong increases employment during this period, most economists were expecting that the U.S. economy would experience a recession at some point during 2022 or 2023. This expectation was reinforced when inflation soared during the summer of 2022 and it became clear that the FOMC would have to substantially raise its target for the federal funds rate.

Clearly, today’s data on real GDP growth, along with the strong September employment report (which we discuss in this blog post), indicates that the chances of the U.S. economy avoiding a recession in the future have increased and are much better than they seemed at this time last year.

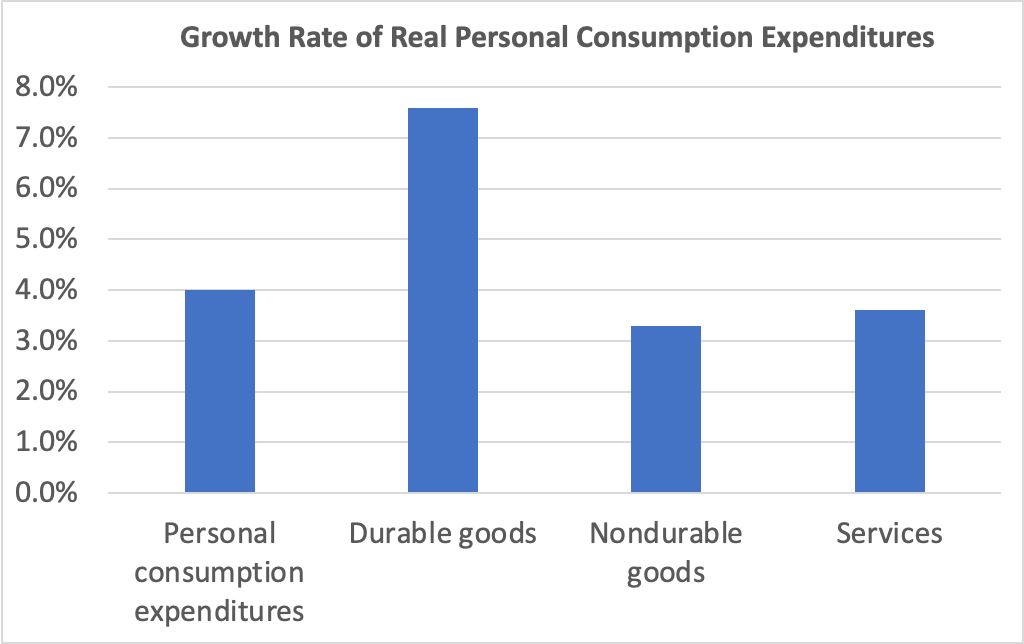

Consumer spending was the largest contributor to third quarter GDP growth. The following figure shows growth rates of real personal consumption expenditures and the subcategories of expenditures on durable goods, nondurable goods, and services. There was strong growth in each component of consumption spending. The 7.6 percent increase in expenditures on durables was particularly strong, particularly given that spending on durables had fallen by 0.3 percent in the second quarter.

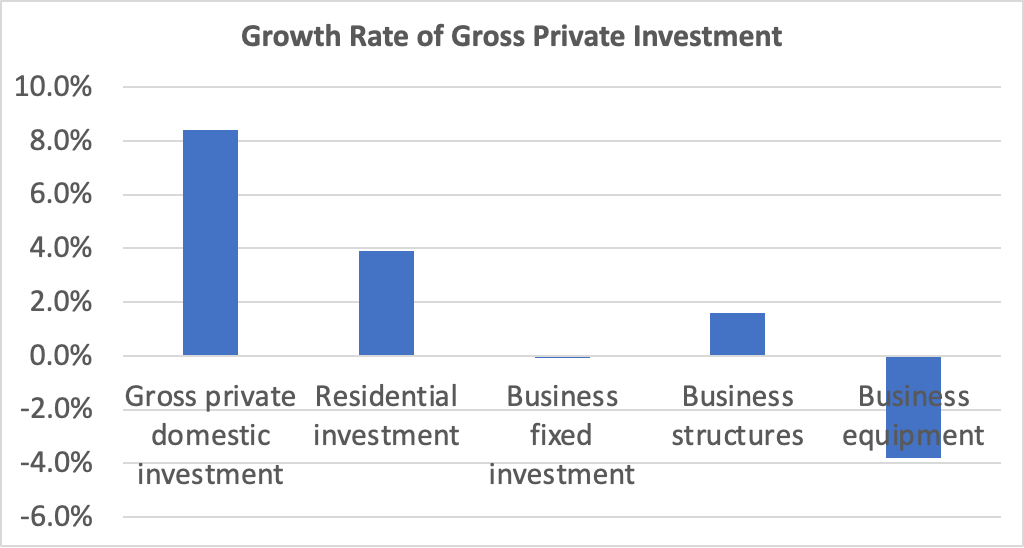

Investment spending and its components were a more mixed bag, as shown in the following figure. Overall, gross private domestic investment increased at a very strong rate of 8.4 percent—the highest rate since the fourth quarter of 2021. Residential investment increased 3.9 percent, which was particularly notable following nine consecutive quarters of decline and during a period of soaring mortgage interest rates. But business fixed investment was noticeably weak, falling by 0.1 percent. Spending on structures—such as factories and office buildings—increased by only 1.6 percent, while spending on equipment fell by 3.8 percent.

Today’s real GDP report also contained data on the private consumption expenditure (PCE) price index, which the FOMC uses tp determine whether it is achieving its goal of a 2 percent inflation rate. The following figure shows inflation as measured using the PCE and the core PCE—which excludes food and energy prices—since the beginning of 2015. (Note that these inflation rates are measured using quarterly data and as compound annual rates of change.) Despite the strong growth in real GDP and employment, inflation as measured by PCE increased only from 2.5 percent in the second quarter to 2.9 percent in the third quarter. Core PCE, which may be a better indicator of the likely course of inflation in the future, continued the long decline that began in first quarter of 2022 by failling from 3.7 percent to 2.9 percent.

The combination of strong growth in real GDP and declining inflation indicates that the Fed appears well on its way to a soft landing—achieving a return to its 2 percent inflation target without pushing the economy into a recession. There are reasons to be cautious, however.

GDP, inflation, and employment data are all subject to—possibly substantial—revisions. So growth may have been significantly slower than today’s advance estimate of real GDP indicates. Even if the estimate of real GDP growth of 4.9 percent proves in the long run to have been accurate, there are reasons to doubt whether output growth can be maintained at near that level. Since 2000, annual growth in real GDP has average only 2.1 percent. For GDP to begin increasing at a rate substantially higher than that would require a significant expansion in the labor force and an increase in productivity. While either or both of those changes may occur, they don’t seem likely as of now.

In addition, the largest contributor to GDP growth in the third quarter was from consumption expenditures. As households continue to draw down the savings they built up as a result of the federal government’s response to the Covid recession of 2020, it seems unlikely that the current pace of consumer spending can be maintained. Finally, the lagged effects of monetary policy—particularly the effects of the interest rate on the 10-year Treasury note having risen to nearly 5 percent (which we discuss in our most recent podcast)—may substantially reduce growth in real GDP and employment in future quarters.

But those points shouldn’t distract from the fact that today’s GDP report was good news for the economy.