The recession that resulted from the Covid-19 pandemic affected most sectors of the U.S. economy, but some sectors of the economy fared better than others. As a broad generalization, we can say that online retailers, such as Amazon; delivery firms, such as FedEx and DoorDash; many manufacturers, including GM, Tesla, and other automobile firms; and firms, such as Zoom, that facilitate online meetings and lessons, have done well. Again, generalizing broadly, firms that supply a service, particularly if doing so requires in-person contact, have done poorly. Examples are restaurants, movie theaters, hotels, hair salons, and gyms.

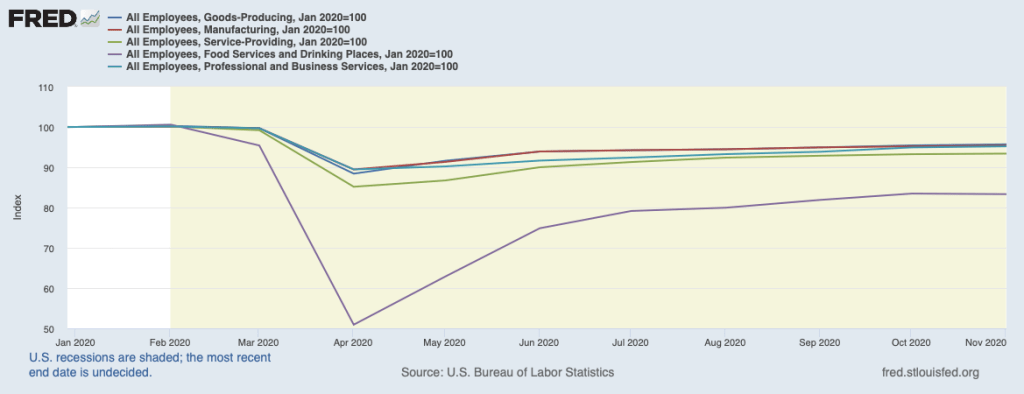

The following figure uses data from the Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) website (fred.stlouisfed.org) on employment in several business sectors—note that the sectors shown in the figure do not account for all employment in the U.S. economy. For ease of comparison, total employment in each sector in February 2020 has been set equal to 100.

Employment in each sector dropped sharply between February and April as the pandemic began to spread throughout the United States, leading governors and mayors to order many businesses and schools closed. Even in areas where most businesses remained open, many people became reluctant to shop in stores, eat in restaurants, or exercise in gyms. From April to November, there were substantial employment gains in each sector, with employment in all goods-producing industries and employment in manufacturing (a subcategory of goods-producing industries) in November being just 5 percent less than in February. Employment in professional and business services (firms in this sector include legal, accounting, engineering, legal, consulting, and business software firms), rose to about the same level, but employment in all service industries was still 7 percent below its February level and employment in restaurants and bars was 17 percent below its February level.

Raj Chetty of Harvard University and colleagues have created the Opportunity Insights website that brings together data on a number of economic indicators that reflect employment, income, spending, and production in geographic areas down to the county or, for some cities, the ZIP code level. The Opportunity Insights website can be found HERE.

In a paper using these data, Chetty and colleagues find that during the pandemic “spending fell primarily because high-income households started spending much less.… Spending reductions were concentrated in services that require in-person physical interaction, such as hotels and restaurants …. These findings suggest that high-income households reduced spending primarily because of health concerns rather than a reduction in income or wealth, perhaps because they were able to self-isolate more easily than lower-income individuals (e.g., by substituting to remote work).”

As a result, “Small business revenues in the highest-income and highest-rent ZIP codes (e.g., the Upper East Side of Manhattan) fell by more than 65% between March and mid-April, compared with 30% in the least affluent ZIP codes. These reductions in revenue resulted in a much higher rate of small business closure in affluent areas within a given county than in less affluent areas.” As the revenues of small businesses declined, the businesses laid off workers and sometimes reduced the wages of workers they continued to employ. The employees of these small businesses, were typically lower- wage workers. The authors conclude from the data that: “Employment for high- wage workers also rebounded much more quickly: employment levels for workers in the top wage quartile [the top 20 percent of wages] were almost back to pre-COVID levels by the end of May, but remained 20% below baseline for low-wage workers even as of October 2020.”

The paper, which goes into much greater detail than the brief summary just given, can be found HERE.