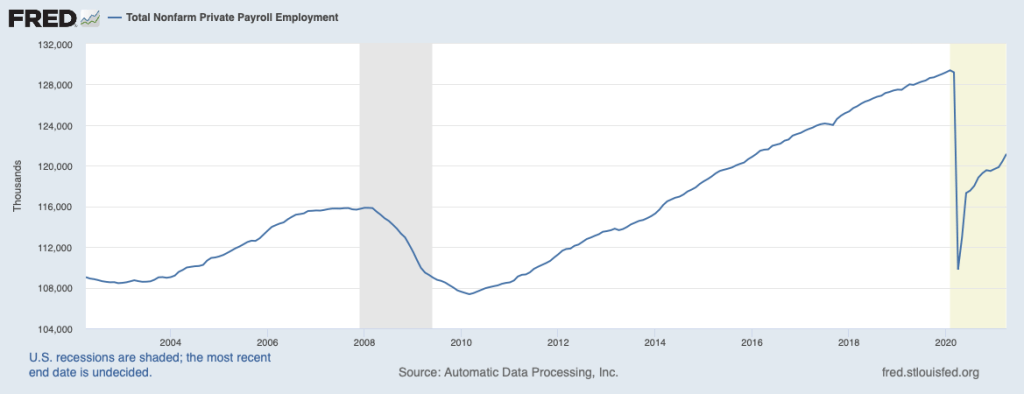

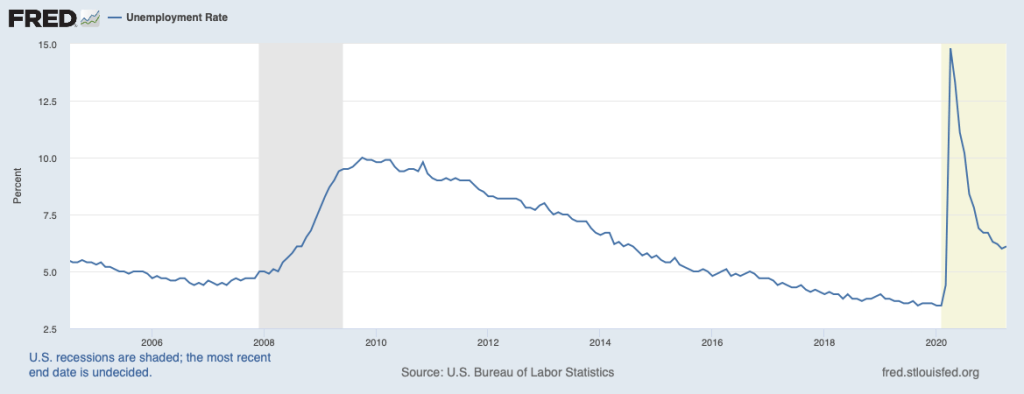

On Friday May 7, 2021, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released its monthly “Employment Situation Report.” The BLS estimated that nonfarm payroll employment had increased by 266,000 from March to April. The average forecast of the Wall Street Journal’s panel of economists was for a much higher increase in employment of 1 million. The unemployment rate increased from 6.0% to 6.1%, rather than falling to 5.8% as economists had forecast.

Keep in mind that employment data is subject to revisions. What does this employment report tell us about the state of the economy and the state of the labor market? First, it’s always worth remembering that the BLS revises its employment estimates at least three times in subsequent months as more complete data become available. (The unemployment rate estimates are calculated in a separate survey of households and are not revised other than as seasonal adjustment factors change.)

Employment data gathered during and immediately after a recession are particularly subject to large revisions. In the principles textbook, Chapter 19, Section 19.1 includes a discussion of the substantial revisions the BLS made to its initial employment estimates during the 2007–2009 recession. Today’s report noted that the increase in employment from February to March, which had originally been reported as 916,000 had been revised downward to 770,000.

Explaining the slow increase in employment. So, the estimated employment increase the BLS reported today may well end up being revised upward. But the revisions will almost certainly leave the increase far short of the forecast increase of 1 million. We can discuss two types of explanations for this relatively disappointing employment increase: 1) factors affecting the demand for labor, and 2) factors affecting the supply of labor.

The demand for labor. During the recovery from a typical recession, increases in labor demand may lag behind increases in production, limiting employment increases and causing temporary increases in the unemployment rate. Employers may be reluctant to hire more workers if the employers are uncertain that the increase in demand for their products will be maintained. During a recession, firms also typically reduce employment by less than they reduce output because searching for workers during a recovery is costly and because they may fear that if they lay off their most productive workers, these workers may accept jobs at competing firms. As a result, during the early months of a recovery, firms are in position to increase output by more than they increase employment. That this outcome occurred during the first months of 2021 is indicated by the fact that productivity increased 5.4% during the first quarter of 2021, as firms increased output by 8.4% but hours worked by only 2.9%.

The recession caused by the pandemic was unusual in that many businesses decreased their supply of goods and services not because of a decline in consumer demand but because of government social distancing requirements. During March 2021, as more people became vaccinated against Covid-19, state and local governments in many areas of the country were relaxing or eliminating these requirements. But upsurges in infection in some areas slowed this process and may also have made consumers reluctant to shop at stores or attend movie theaters even where such activities were not restricted. Finally, partly due to the pandemic, some U.S. manufacturers were having trouble receiving deliveries of intermediate goods. In particular, automobile companies had to reduce production or close some factories because of the difficulty of obtaining computer chips. As a result, during April 2021, employment declined in the motor vehicle and parts industry despite strong consumer demand for cars and light trucks.

The supply of labor. In the weeks leading up to the release of employment report, the media published many articles focusing on firms that were having difficulty hiring workers. BLS data for February 2021 (the most recent month with available data) showed that the estimated number of job opening nationwide was actually 5% higher than in February 2020, the last month before the pandemic.

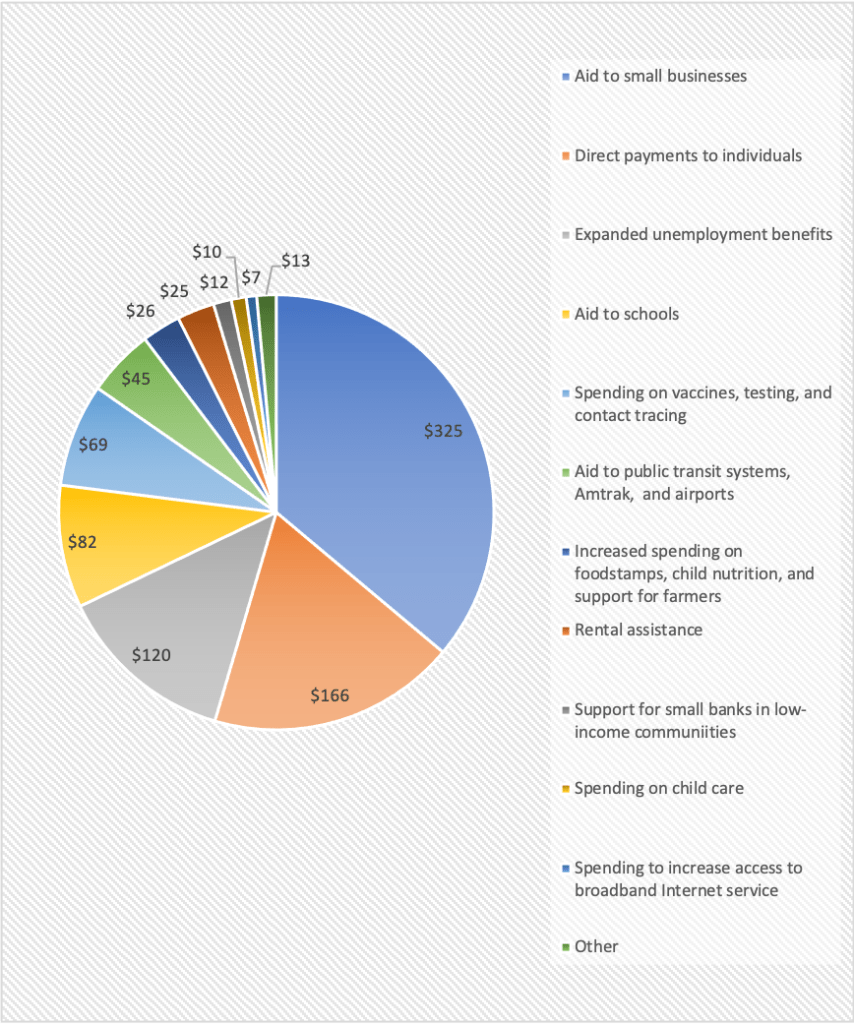

That employment grew slowly despite a large number of available jobs may be an indication that labor supply had declined relative to the situation before the pandemic. That is, fewer people were willing to work at any given wage than a year earlier. There are several related reasons that the labor supply curve may have shifted: 1) Many K-12 schools were still conducting instruction either wholly or partially online making it more difficult for parents of school-age children to accept work outside the home; 2) although vaccinations had become widely available, some people were still hesitant to be in close proximity to other people as is required in many jobs; and 3) under the American Rescue Plan Act proposed by President Biden and passed by Congress in March 2021, many unemployed workers were eligible for an additional $300-per-week federal payment on top of their normal state unemployment insurance payment. These expanded unemployment benefits were scheduled to end September 2021. In the case of some low-wage workers, their total unemployment payment during April was greater than the wage they would have earned if employed.

These three factors affecting labor supply were potentially interrelated in that the expanded unemployment insurance benefits provided the financial means that allowed some workers to remain unemployed so that they could be home with their children or so that they could avoid a work situation that they believed exposed them to the risk of contracting Covid-19.

That at least some firms were having difficulty hiring workers seemed confirmed by the fact that average weekly hours worked steadily increased from February through April, indicating that employers were asking their existing employees to work longer hours.

Summary. It’s never a good idea to draw firm conclusions about the state of the economy from one month’s employment report. That observation is particularly true in this case because April 2021 was a period of continuing transition in the U.S. economy as vaccination rates increased, infection rates declined, and government restrictions on business operations were relaxed. All of these factors made it likely that during the following months more businesses would be able to resume normal operations, increasing the demand for labor.

In addition, by the fall, the factors affecting labor supply may have largely been resolved as most children return to full-time on-site schooling, increased vaccination rates reduce fears of infection, and the supplementary unemployment benefits end.

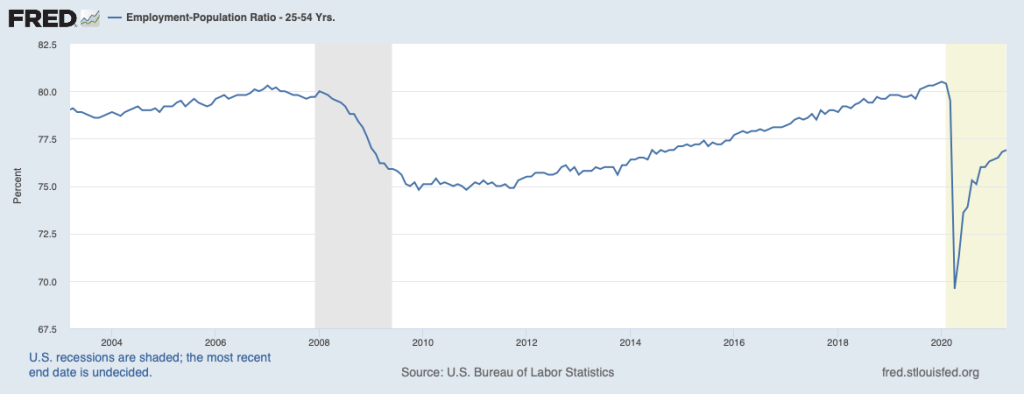

The three figures below show: 1) total nonfarm private employment; 2) the employment-population ratio for workers aged 25 to 54; and 3) the unemployment rate. Together the figures indicate that in April 2021 the recovery from the worst effects of the pandemic on the labor market was well underway, but there was still a long way to go.