Should you just throw these away?

It’s not surprising that waste management firms often recycle metals that have either been separated by households and firms in recycling bins or have been thrown away mixed in with other trash. But according to a recent article in the Wall Street Journal, Reworld, a nationwide waste management firm headquartered in Morristown, New Jersey, has been recovering metal that you wouldn’t ordinarily expect to find in garbage: U.S. coins. Are these coins that people have accidentally thrown in the garbage? Some of the coins were probably mistakenly included in garbage but the article indicates that most were likely intentionally thrown away:

“Coins are as good as junk for many Americans…. [Many people believe that] change is often more trouble than it is worth to carry around.”

Why would people throw coins—things of obvious value—into the garbarge? As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 14, Section 14.1 (Economics, Chapter 24, Sextion 24.1 and Essentials of Economics, Chapter 16, Section 16.1), consumers have been buying things using paper money and coins much less frequently in recent years. People have relied more on making purchases or transferring funds using credit and debit cards, Apple Pay and Google Pay, or smartphones apps like Venmo.

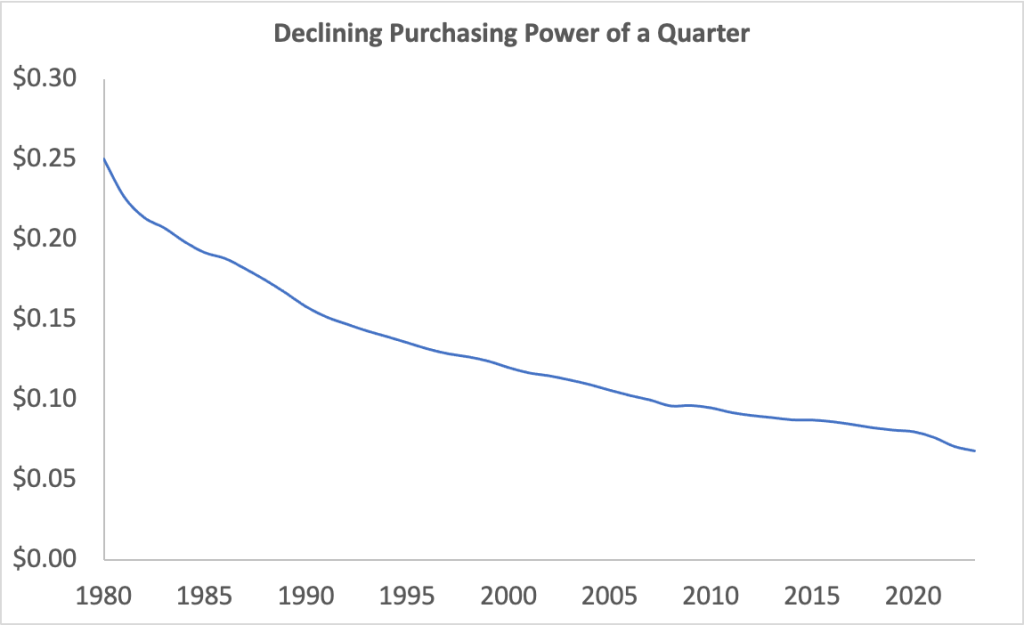

Even if people use cash to buy things, they are more likely to use paper currency rather than coins. As prices increase, the amount of goods or services you can buy with a coin of a given face value decreases. For instance, the following figure shows that with a quarter you could have bought 25 cents worth of goods and services in 1980 but, because of inflation, only 7 cents worth of goods and services in 2023.

In other words, coins have become less useful both because more convenient means of payment, such as Apple Pay or Venmo, have become more widely and available and because inflation has eroded the purchasing power of coins. In addition, for decades, drinks, snacks, and other products sold from vending machines could only be purchased using coins. But in recent years, most vending machines have been modified to accept credit cards. Because fewer people use coins to buy things, if they receive coins in change after paying with paper currency, they are likely to just accumulate the coins in a jar or other container or, as Reworld has discovered, throw the coins in the garbage.

If an increasing number of coins are being thrown away, should the government stop minting them? It’s unlikely that the U.S. Mint will stop producing all coins, but there have been serious proposals to at least stop producing the penny and, perhaps, also the nickel. Governments make a profit from issuing money because it is usually produced using paper or low-value metals that cost far less than the face value of the money. The government’s profit from issuing money is called seigniorage.

As the following figure shows (cents are measured on the vertical axis), in recent decades, the penny and the nickel have cost more to produce than their face value. In other words, the federal government has experienced negative seigniorage in minting pennies and nickels, paying more to produce them than they are worth. For instance, in 2023, as the blue line shows, it cost 3.1 cents to produce a penny and distribute it to Federal Reserve Banks (which, in turn, distribute coins to local commercial banks). Similarly, each nickel (the orange line) cost 11.5 cents to produce and distribute. The penny is made from copper and zinc and the other coins are made from copper and nickel. As the market prices of these metals change, so does the cost to the Mint of producing the coins, as shown in the figure.

Data in the figure were compiled from the U.S. Mint’s biennial reports to Congress.

François Velde, an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, has come up with a possible solution to the problem of the penny: The federal government would simply declare that Lincoln pennies are now worth five cents. There would then be two five-cent coins in circulation—the current Jefferson nickels and the current Lincoln pennies—and no one-cent coins. In the future, only the Lincoln coins—now worth five cents—would be minted. This would solve the problem of consumers and retail stores having to deal with pennies, it would make the face value of the Lincoln five-cent coin greater than its cost of production, and it would also deal with the problem that the current Jefferson nickel costs more than five cents to produce.

With some consumers valuing coins so little that they throw them out in the trash and with the U.S. Mint spending more than their face value to produce pennies and nickels, it seems likely that at some point Congress will make changes to U.S. coinage.