Action Comics No. 1, published in June 1938, is often consider the first superhero comic book. (Image from comics.org.)

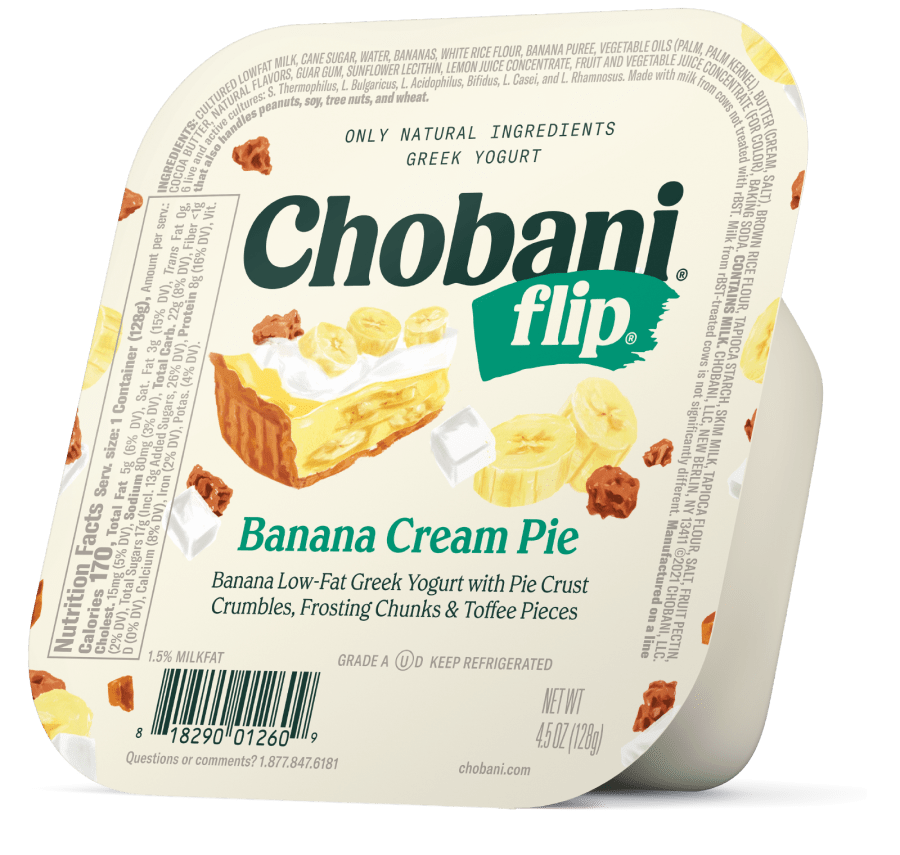

In a political advertisement that ran before the broadcast of the Super Bowl, President Joe Biden discussed shrinkflation, which refers to firms reducing the quantity of a product in container while keeping the price unchanged. In this post from the summer of 2022, we discussed examples of shrinkflation—including Chobani reducing the quantity of yogurt in the package shown here from 5.3 ounces to 4.5 ounces—and noted that shrinkflation complicates the job of the Bureau of Labor Statistics when compiling the consumer price index.

This yogurt remained the same price although the quantity of yogurt in the container shrank from 5.3 ounces to 4.5 ounces.

Shrinkflation isn’t new; firms have used the strategy for decades. Firms are particularly likely to use shrinkflation during periods of high inflation or during periods when the federal government implements price controls. Firms also sometimes resort to shrinkflation when the the price of a product has remained constant for long enough that the firms fear that consumers will react strongly to the firms increasing the price.

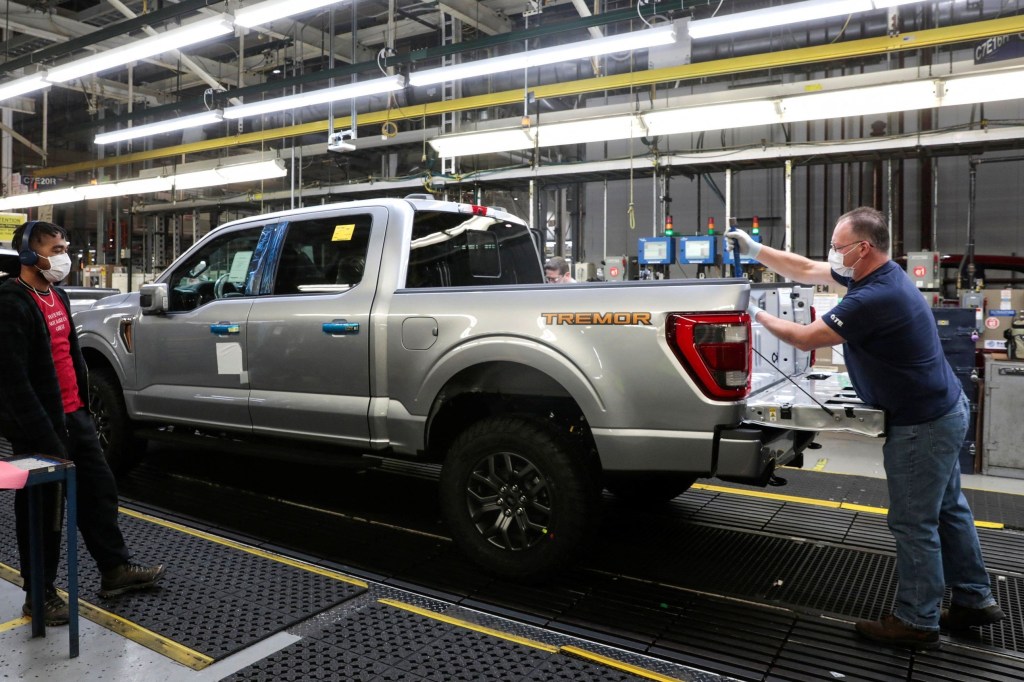

Comic books provide an interesting historical example of shrinkflation. David Palmer, a professor of management at South Dakota State University published an article in 2010 in which he presented data on the price and number of pages in copies of Action Comics from 1938 to 2010. When DC Comics introduced Superman in the first issue of Action Comics in June 1938, it started the superhero genre of comic books. Action Comics No. 1 had a price of $0.10 and was 64 pages.

After the United States entered World War II in December 1941, the federal government imposed price controls to try to limit the inflation caused by the surge in spending to fight the war. Rising costs of producing comic books, combined with the difficulty in raising prices because of the controls, led comic book publishers to engage in shrinkflation. In 1943, the publishers reduced the number of pages in their comics from 64 to 56. In 1944, the publishers engaged in further shrinkflation, reducing the number of pages from 56 to 48.

In 1951, during the Korean War, the federal government again imposed price controls. Comic book publishers responded with further shrinkflation, keeping the price at $0.10, while reducing the number of pages from 48 to 40. In 1954, they shrank the number of pages to 36, which remains the most common number of pages in a comic book today. At that time, the publishers also slightly reduced the width of comics from 7 3/4 inches to 7 1/8 inches. (Today the typical comic book has a width of 6 7/8 inches.)

By the late 1950s, comic book publishers became convinced that they would be better off raising the prices of comic books rather than further shrinking the number of pages. But they were reluctant to raise their prices because they had been a constant $0.10 for more than 20 years, so children and their parents might react very negatively to a price increase, and because no firm wanted to be the first to raise its price for fear of losing sales to its competitors. They were caught in a prisoner’s dilemma: Comic book publishers would all have been better off if they had raised their prices but the antitrust laws kept them from colluding to raise prices and no individual firm had an incentive to raise prices alone. (We discuss collusion, prisoner’s dilemmas, and other aspects of oligopolistic firm behaviour in Chapter 14 of Microeconomics and Economics.)

The most successful publisher in the 1950s was Dell, which sold very popular comic books featuring Donald Duck, Uncle Scrooge, and other characters that particularly appealed to younger children. Because the prices of Dell’s comic books, like those of other publishers, been unchanged at $0.10 since the late 1930s, the firm didn’t have a clear idea of the price elasticity of demand for its comics. In 1957, the firm’s managers decided to use a market experiment to gather data on the price elasticity of demand. In most cities, Dell kept the price of its comics at $0.10, but in some cities it sold the identical comics at a price of $0.15.

The experiment lasted from March 1957 to August 1958 when the company discontinued it by reverting to selling all of its comics for $0.10. Although we lack the data necessary to compare the sales of Dell comics with a $0.15 price to the sales of Dell comics with a $0.10 price, the fact that no other publisher raised its prices during that period and that Dell abandoned the experiment indicates that the demand curve for Dell’s comics was price elastic—the percentage decline in the quantity sold was greater than the 50 percent increase in price—so Dell’s revenue from sales in the cities selling comics with a price of $0.15 likely declined. Dell’s strategy can be seen as a failed example of price leadership. (We discuss the relationship between the price elasticity of demand for a good and the total revenue a firm earns from selling the good in Chapter 6, Section 6.3 of Microeconomics and Economics. We discuss price leadership in Microeconomic and Economics, Chapter 14, Section 14.2.)

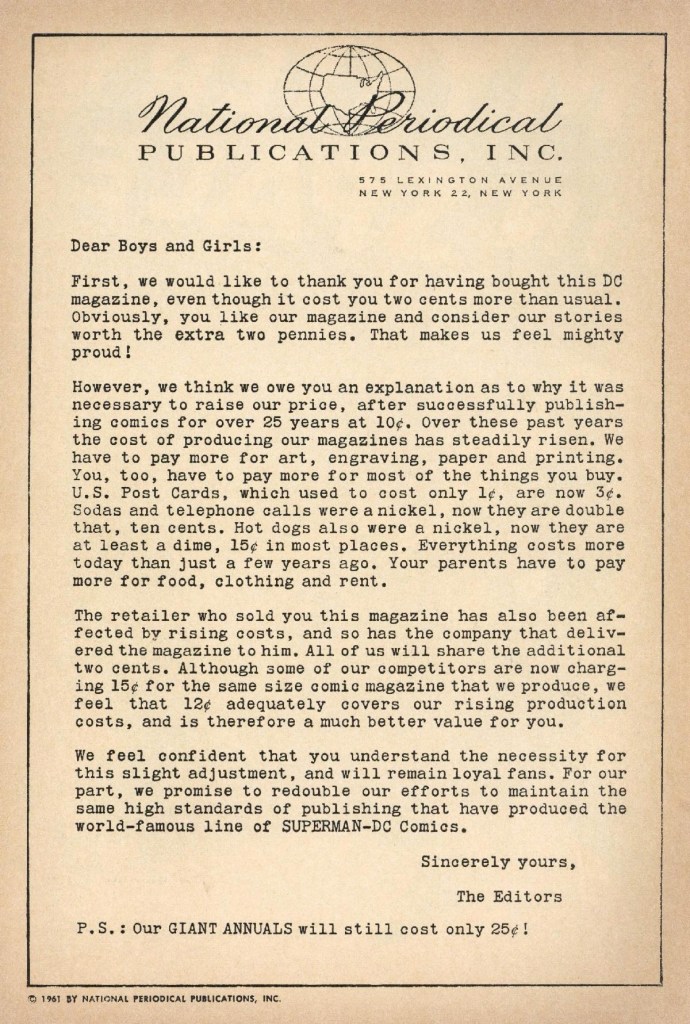

In March 1961, Dell increased the price of all of its comics from $0.10 to $0.15. At first, Dell’s competitors kept the prices of their comics at $0.10. As a result, in September 1961, Dell cut the price of its comics from $0.15 to $0.12. By early 1962, Dell’s competitors, including DC Comics, Marvel Comics—publishers of Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four—along with several smaller publishers, had increased the prices of their comics from $0.10 to $0.12. The managers at DC decided that raising the price of comics after having kept it constant for so long required an explantion. Accordingly, they printed the following letter in each of their comics.

H/T to Buddy Saunders for the image.

Comic book publishers have raised their prices many times since the early 1960s, with most comics currently having a price of $4.99. During the recent period of high inflation, comic publishers did not use a strategy of shrinkflation perhaps because they believe that 36 pages is the minimum number that buyers will accept.

The first 25 years of the comic book industry represents an interesting historical example of shrinkflation.