Image generated by ChatGPT

This morning (September 5), the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released its “Employment Situation” report (often called the “jobs report”) for August. The data in the report show that the labor market was weaker than expected in August.

The jobs report has two estimates of the change in employment during the month: one estimate from the establishment survey, often referred to as the payroll survey, and one from the household survey. As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 9, Section 9.1 (Economics, Chapter 19, Section 19.1), many economists and Federal Reserve policymakers believe that employment data from the establishment survey provide a more accurate indicator of the state of the labor market than do the household survey’s employment data and unemployment data. (The groups included in the employment estimates from the two surveys are somewhat different, as we discuss in this post.)

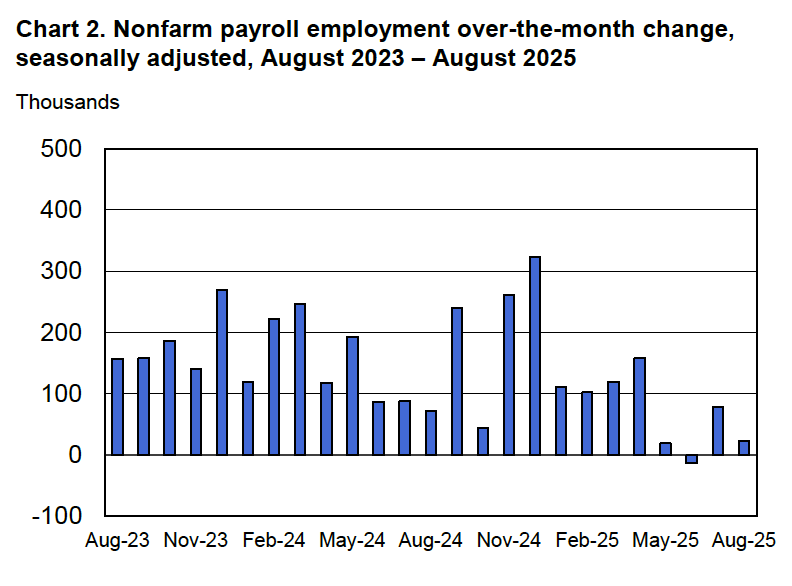

According to the establishment survey, there was a net increase of only 22,000 nonfarm jobs during August. This increase was well below the increase of 110,000 that economists surveyed by FactSet had forecast. Economists surveyed by the Wall Street Journal had forecast a smaller increase of 75,000 jobs. In addition, the BLS revised downward its previous estimates of employment in June and July by a combined 21,000 jobs. The estimate for June was revised from a net gain of 14,000 to a net loss of 13,000. This was the first month with a net job loss since December 2020. (The BLS notes that: “Monthly revisions result from additional reports received from businesses and government agencies since the last published estimates and from the recalculation of seasonal factors.”)

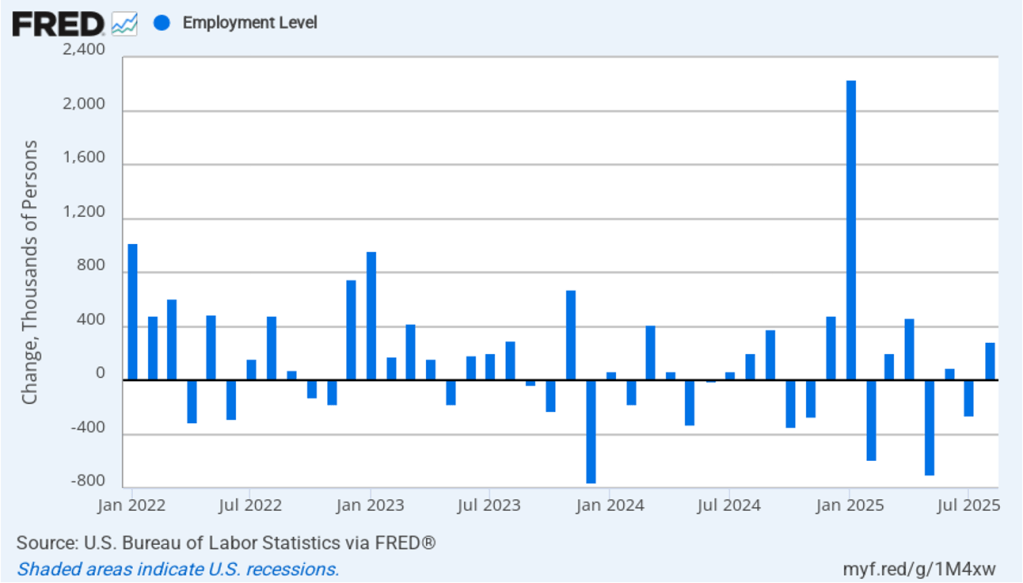

The following figure from the jobs report shows the net change in nonfarm payroll employment for each month in the last two years. The figure makes clear the striking deceleration in job growth since April. The Trump administration announced sharp increases in U.S. tariffs on April 2. Media reports indicate that some firms have slowed hiring due to the effects of the tariffs or in anticipation of those effects.

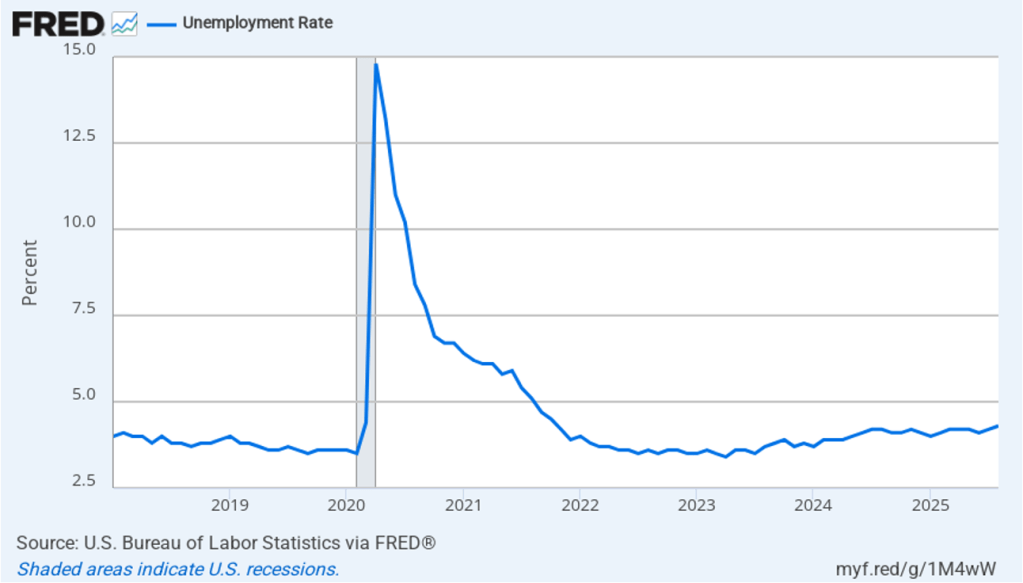

The unemployment rate increased from 4.2 percent in July to 4.3 percent in August, the highest rate since October 2021. The unemployment rate is above the 4.2 percent rate economists surveyed by FactSet had forecast. As the following figure shows, the unemployment rate had been remarkably stable over the past year, staying between 4.0 percent and 4.2 percent in each month May 2024 to July 2025 before breaking out of that range in August. In June, the members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) forecast that the unemployment rate during the fourth quarter of 2025 would average 4.5 percent. The unemployment rate would still have to rise significantly for that forecast to be accurate.

Each month, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta estimates how many net new jobs are required to keep the unemployment rate stable. Given a slowing in the growth of the working-age population due to the aging of the U.S. population and a sharp decline in immigration, the Atlanta Fed currently estimates that the economy would have to create 97,591 net new jobs each month to keep the unemployment rate stable at 4.3 percent. If this estimate is accurate, continuing monthly net job increases of 22,000 would result in a a rising unemployment rate.

As the following figure shows, the monthly net change in jobs from the household survey moves much more erratically than does the net change in jobs from the establishment survey. As measured by the household survey, there was a net increase of 288,000 jobs in August, following a net decrease of 260,000 jobs in July. As an indication of the volatility in the employment changes in the household survey note the very large swings in net new jobs in January and February. In any particular month, the story told by the two surveys can be inconsistent. as was the case this month with employment increasing much more in the household survey than in the employment survey. (In this blog post, we discuss the differences between the employment estimates in the two surveys.)

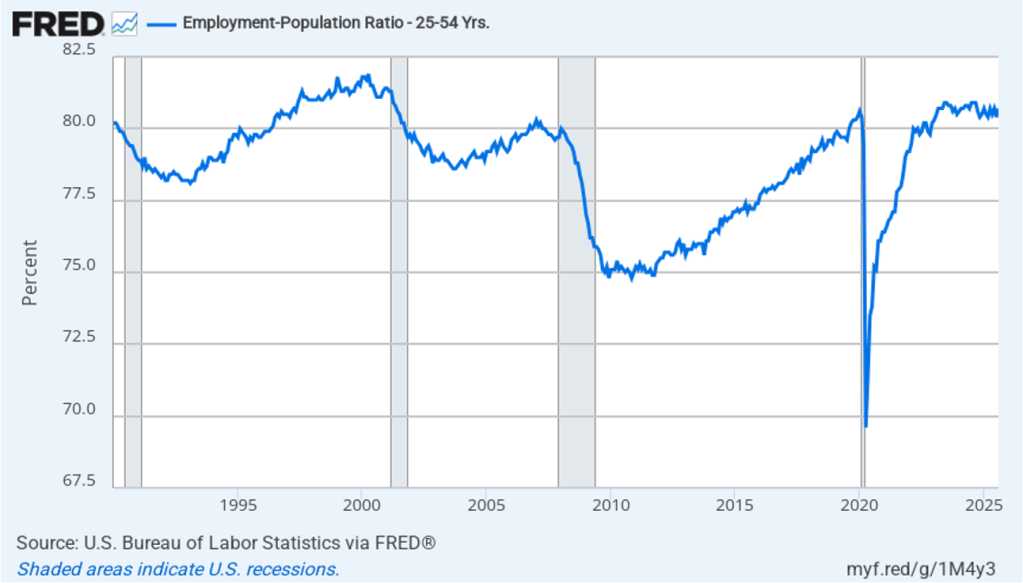

The household survey has another important labor market indicator: the employment-population ratio for prime age workers—those aged 25 to 54. In August the ratio rose to 80.7 percent from 8.4 percent in July. The prime-age employment-population ratio is somewhat below the high of 80.9 percent in mid-2024, but is still above what the ratio was in any month during the period from January 2008 to February 2020. The increase in the prime-age employment-population ratio is a bright spot in this month’s jobs report.

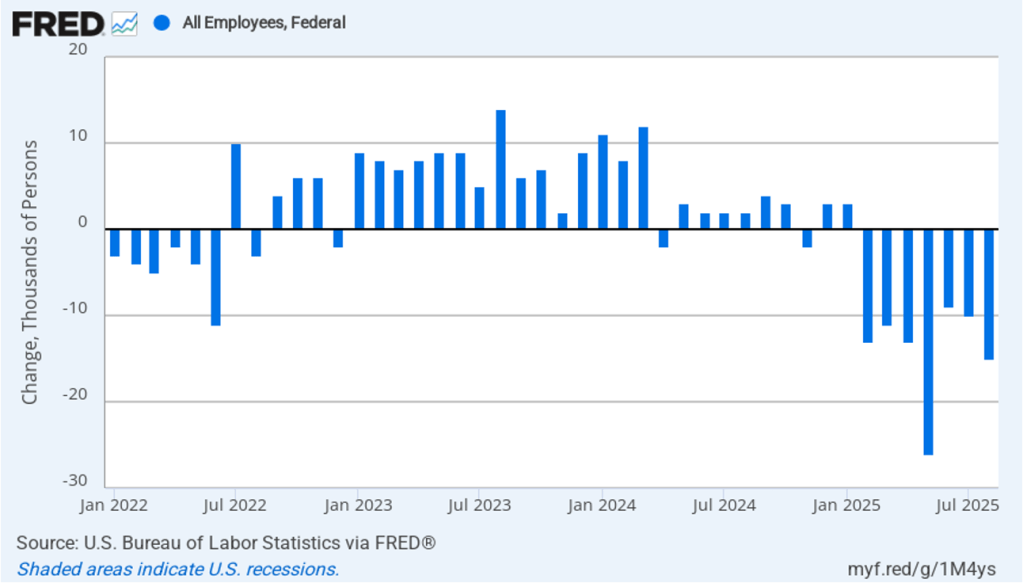

It is still unclear how many federal workers have been laid off since the Trump Administration took office. The establishment survey shows a decline in federal government employment of 15,000 in August and a total decline of 97,000 since the beginning of February 2025. However, the BLS notes that: “Employees on paid leave or receiving ongoing severance pay are counted as employed in the establishment survey.” It’s possible that as more federal employees end their period of receiving severance pay, future jobs reports may report a larger decline in federal employment. To this point, the decline in federal employment has had a small effect on the overall labor market.

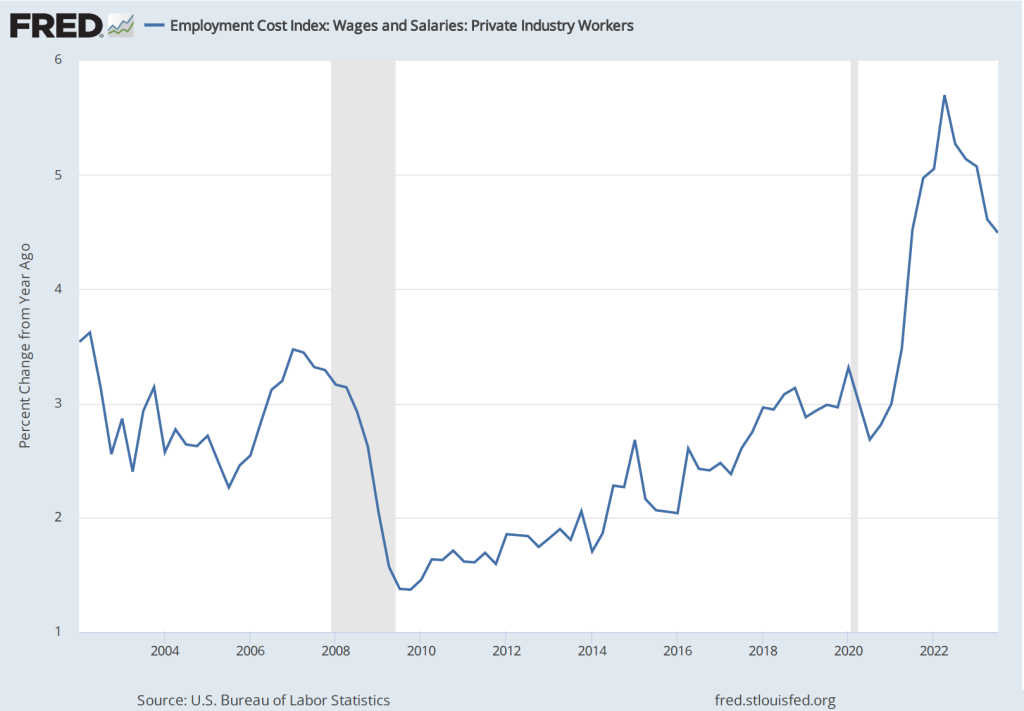

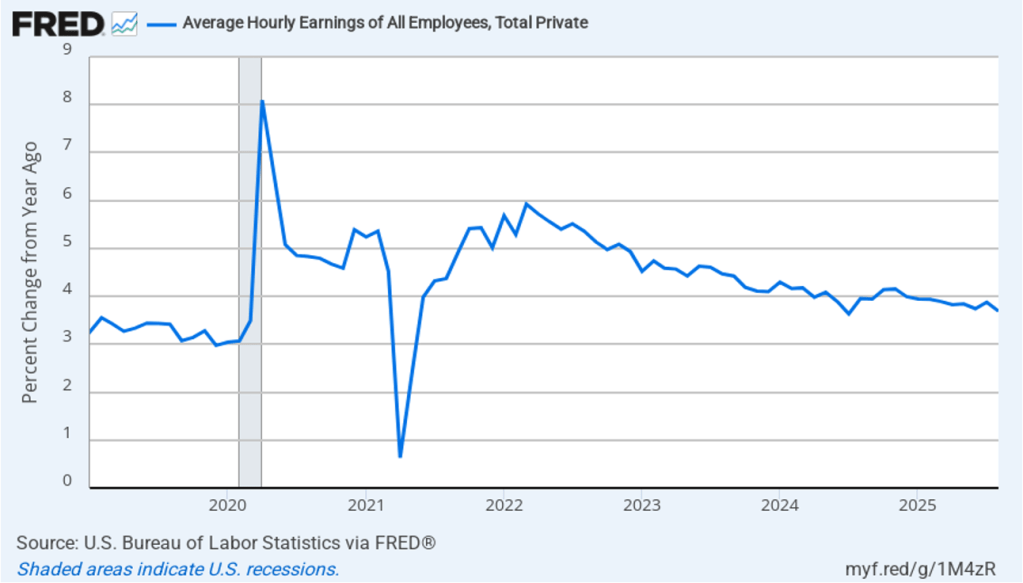

The establishment survey also includes data on average hourly earnings (AHE). As we noted in this post, many economists and policymakers believe the employment cost index (ECI) is a better measure of wage pressures in the economy than is the AHE. The AHE does have the important advantage of being available monthly, whereas the ECI is only available quarterly. The following figure shows the percentage change in the AHE from the same month in the previous year. The AHE increased 3.7 percent in August, down from an increase of 3.9 percent in July.

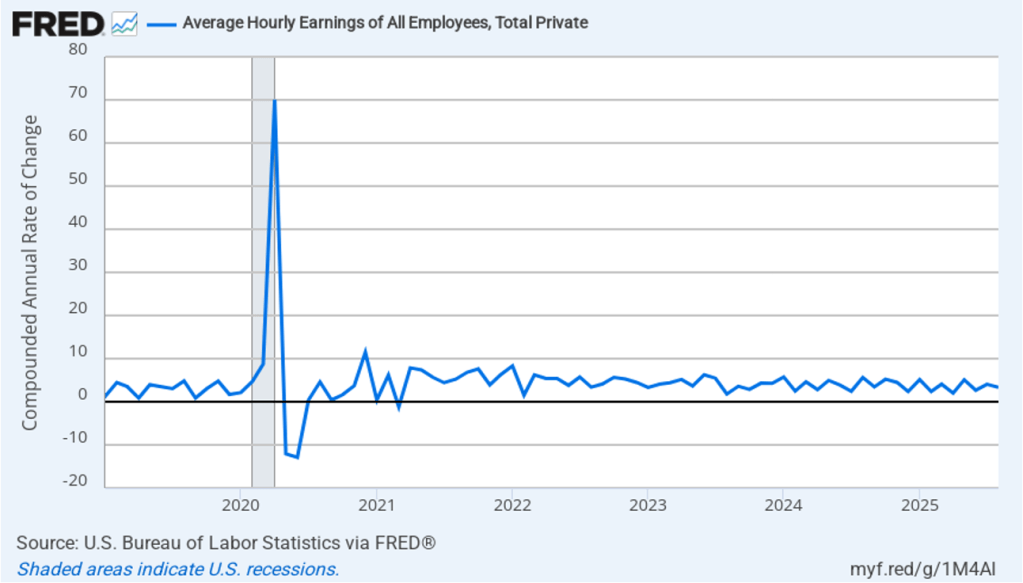

The following figure shows wage inflation calculated by compounding the current month’s rate over an entire year. (The figure above shows what is sometimes called 12-month wage inflation, whereas this figure shows 1-month wage inflation.) One-month wage inflation is much more volatile than 12-month wage inflation—note the very large swings in 1-month wage inflation in April and May 2020 during the business closures caused by the Covid pandemic. In August, the 1-month rate of wage inflation was 3.3 percent, down from 4.0 percent in July. This slowdown in wage growth may be another indication of a weakening labor market. But one month’s data from such a volatile series may not accurately reflect longer-run trends in wage inflation.

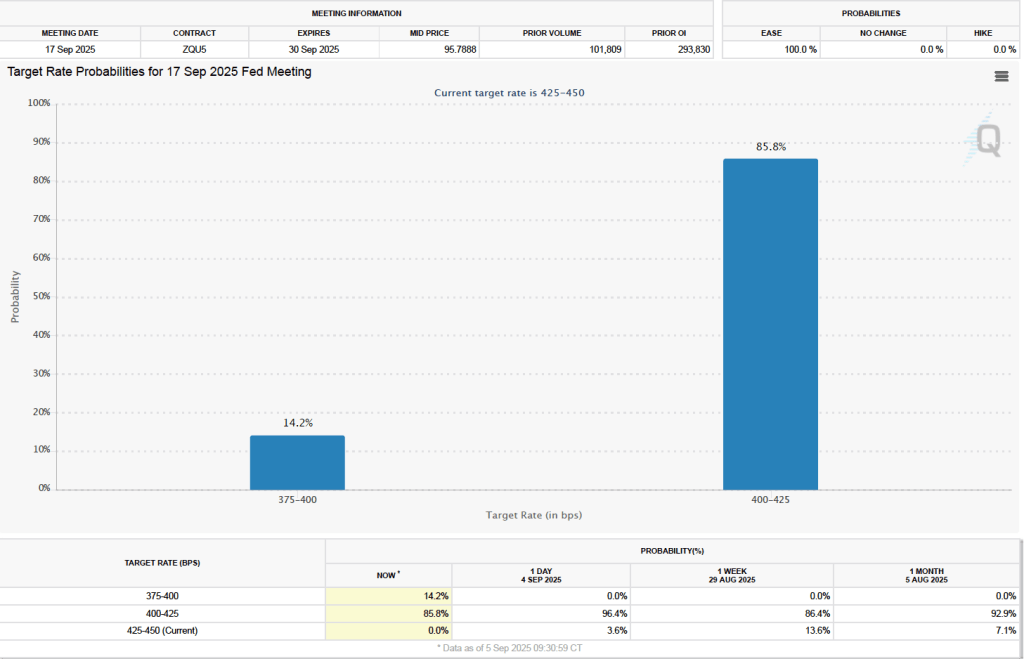

What effect might today’s jobs report have on the decisions of the Federal Reserve’s policymaking Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) with respect to setting its target for the federal funds rate? One indication of expectations of future changes in the FOMC’s target for the federal funds rate comes from investors who buy and sell federal funds futures contracts. (We discuss the futures market for federal funds in this blog post.) As we’ve noted in earlier blog posts, since the weak July jobs report, investors have assigned a very high probability to the committee cutting its target by 0.25 percentage point (25 basis points) from its current range of 4.25 percent to 4.50 percent at its September 16–17 meeting. This morning, as the following figure shows, investors raised the probability they assign to a 50 basis point reduction at the September meeting from 0 percent to 14.2 percent. Investors are also now assigning a 78.4 percent probability to the committee cutting its target range by at least an additional 25 basis points at its October 28–29 meeting.