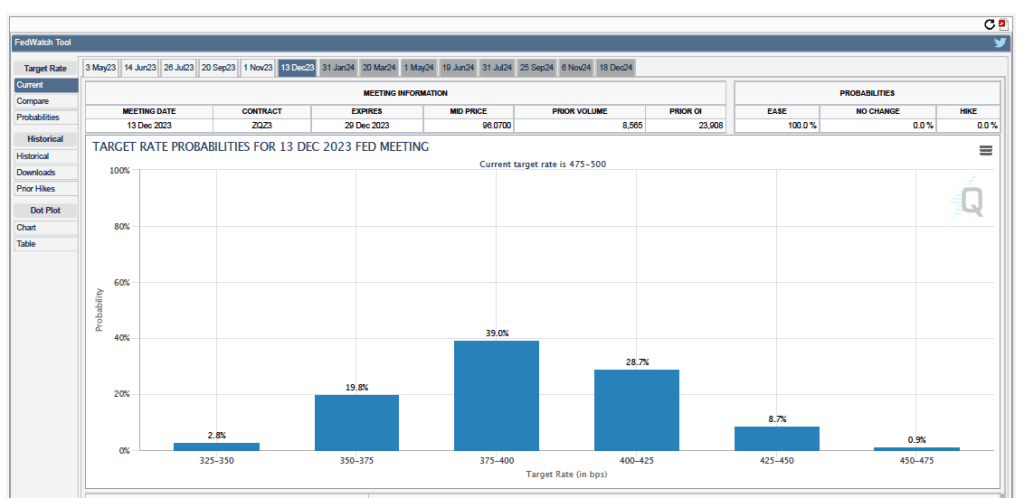

At its Wednesday, May 3, 2023 meeting, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) raised its target for the federal funds rate by 0.25 percentage point to a range of 5.00 to 5.25. The decision by the committee’s 11 voting members was unanimous. After each meeting, the FOMC releases a statement (the statement for this meeting can be found here) explaining its reasons for its actions at the meeting.

The statement for this meeting had a key change from the statement the committee issued after its last meeting on March 22. The previous statement (found here) included this sentence:

“The Committee anticipates that some additional policy firming may be appropriate in order to attain a stance of monetary policy that is sufficiently restrictive to return inflation to 2 percent over time.”

In the statement for this meeting, the committee rewrote that sentence to read:

“In determining the extent to which additional policy firming may be appropriate to return inflation to 2 percent over time, the Committee will take into account the cumulative tightening of monetary policy, the lags with which monetary policy affects economic activity and inflation, and economic and financial developments.”

This change indicates that the FOMC has stopped—or at least suspended—use of forward guidance. As we explain in Money, Banking, and the Financial System, Chapter 15, Section 5.2, forward guidance refers to statements by the FOMC about how it will conduct monetary policy in the future.

After the March meeting, the committee was providing investors, firms, and households with the forward guidance that it intended to continue raising its target for the federal funds rate—which is what the reference to “additional policy firming” means. The statement after the May meeting indicated that the committee was no longer giving guidance about future changes in its target for the federal funds rate other than to state that it would depend on the future state of the economy. In other words, the committee was indicating that it might not raise its target for the federal funds rate after its next meeting on June 14. The committee didn’t indicate directly that it was pausing further increases in the federal funds rate but indicated that pausing further increases was a possible outcome.

Following the end of the meeting, Fed Chair Jerome Powell conducted a press conference. Although not yet available when this post was written, a transcript will be posted to the Fed’s website here. Powell made the following points in response to questions:

- He was not willing to move beyond the formal statement to indicate that the committee would pause further rate increases.

- He believed that the bank runs that had led to the closure and sale of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and First Republic Bank were likely to be over. He didn’t believe that other regional banks were likely to experience runs. He indicated that the Fed needed to adjust its regulatory and supervisory actions to help ensure that similar runs didn’t happen in the future.

- He repeated that he believed that the Fed could achieve its target inflation rate of 2 percent without the U.S. economy experiencing a recession. In other words, he believed that a soft landing was still possible. He acknowledged that some other members of the committee and the committee’s staff economist disagreed with him and expected a mild recession to occur later this year.

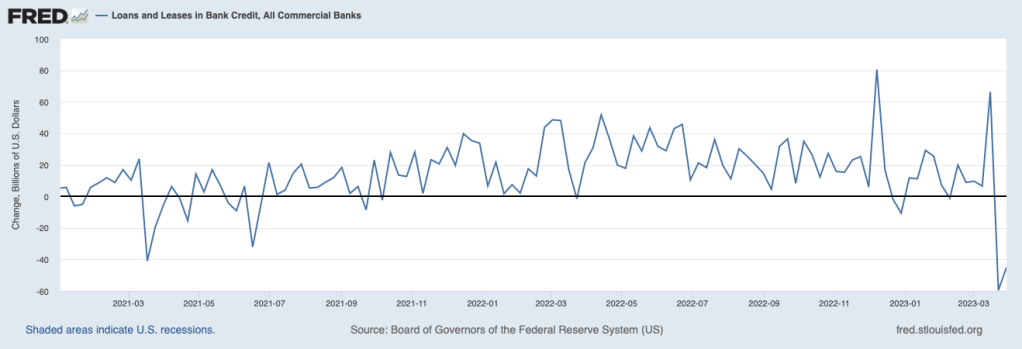

- He stated that as banks have attempted to become more liquid following the failure of the three regional banks, they have reduced the volume of loans they are making. This credit contraction has an effect on the economy similar to that of an increase in the federal funds rate in that increases in the target for the federal funds rate are also intended to reduce demand for goods, such as housing and business fixed investment, that depend on borrowing. He noted that both those sectors had been contracting in recent months, slowing the economy and potentially reducing the inflation rate.

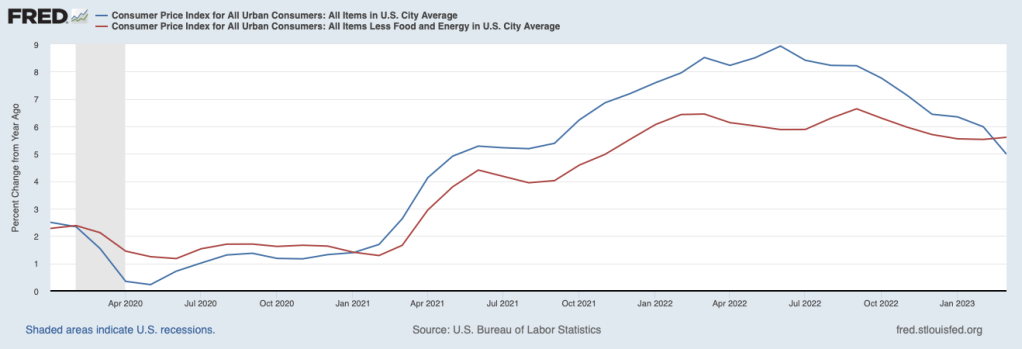

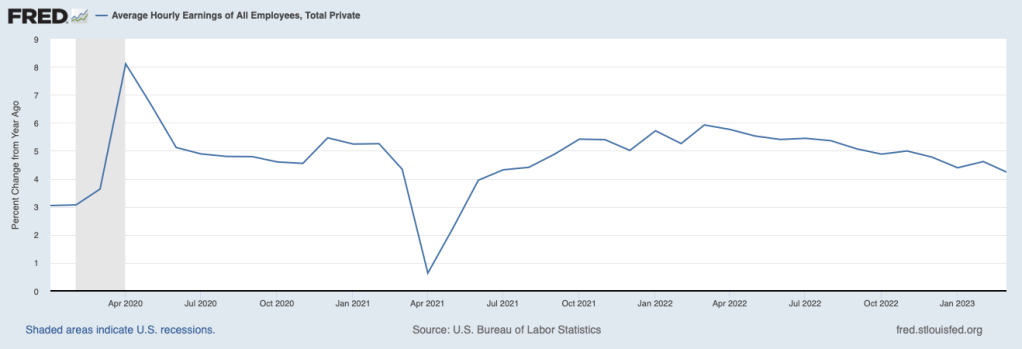

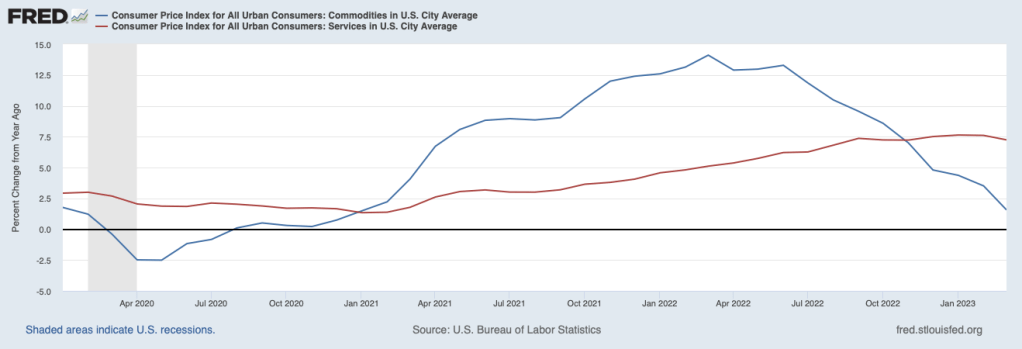

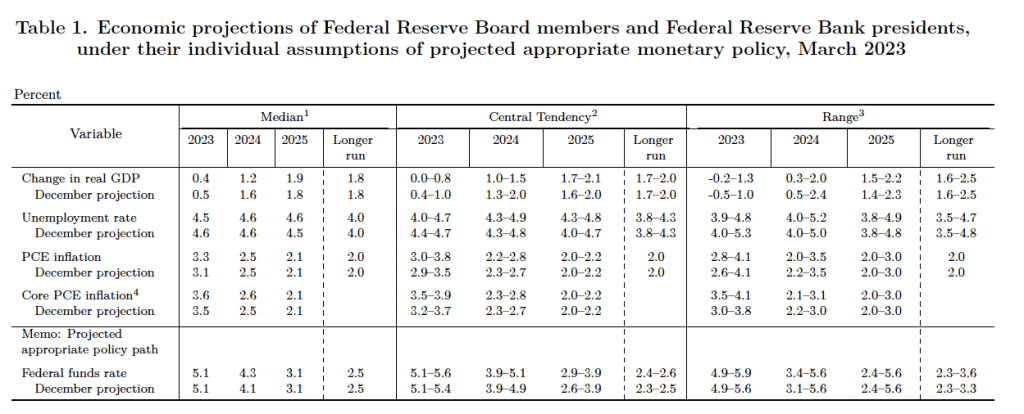

- He indicated that although inflation had declined somewhat during the past year, it was still well above the Fed’s target. He mentioned that wage increases were still higher than is consistent with an inflation rate of 2 percent. In response to a question, he indicated that if the inflation rate were to fall from current rates above 4 percent to 3 percent, the FOMC would not be satisfied to accept that rate. In other words, the FOMC still had a firm target rate of 2 percent.

In summary, the FOMC finds itself in the same situation it has been in since it began raising its target for the federal funds rate in March 2022: Trying to bring high inflation rates back down to its 2 percent target without causing the U.S. economy to experience a significant recession.