Join authors Glenn Hubbard & Tony O’Brien as they react to the jobs report of over 300K jobs created which was way over expectations of about 200K. They consider the impact of this report as the Fed considers the next steps for the economy. Are we on a glide path for a soft landing at 2% inflation or will the Fed reconsider its long-standing target by adopting a higher 3% target? Glenn and Tony offer interesting viewpoints on where this is headed.

Tag: inflation

Latest PCE Report Shows Moderate, but Persistent, Inflation

McDonald’s raising the price of its burgers by 10 percent in 2023 led to a decline in sales. (Photo from mcdonalds.com)

Inflation as measured by changes in the consumer price index (CPI) receives the most attention in the media, but the Federal Reserve looks instead to inflation as measured by changes in personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index when evaluating whether it is meeting its 2 percent inflation target. The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) released PCE data for February as part of its “Personal Income and Outlays” report on March 29.

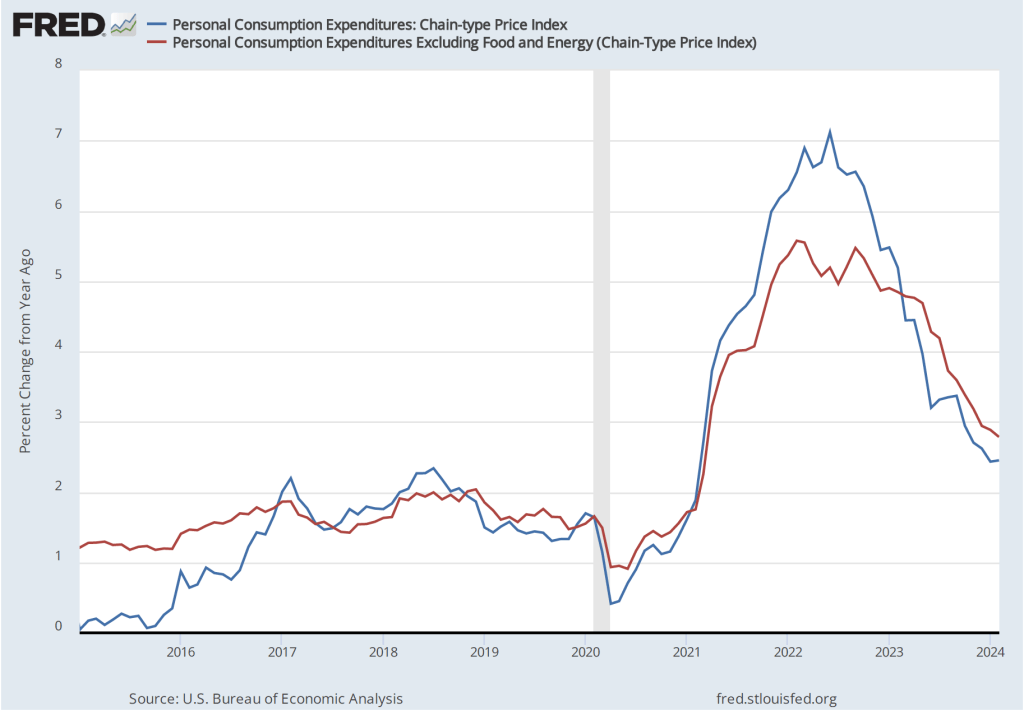

The following figure shows PCE inflation (blue line) and core PCE inflation (red line)—which excludes energy and food prices—for the period since January 2015 with inflation measured as the change in PCE from the same month in the previous year. Measured this way, PCE inflation increased slightly from 2.4 percent in January to 2.5 percent in February. Core PCE inflation decreased slightly from 2.9 percent to 2.8 percent.

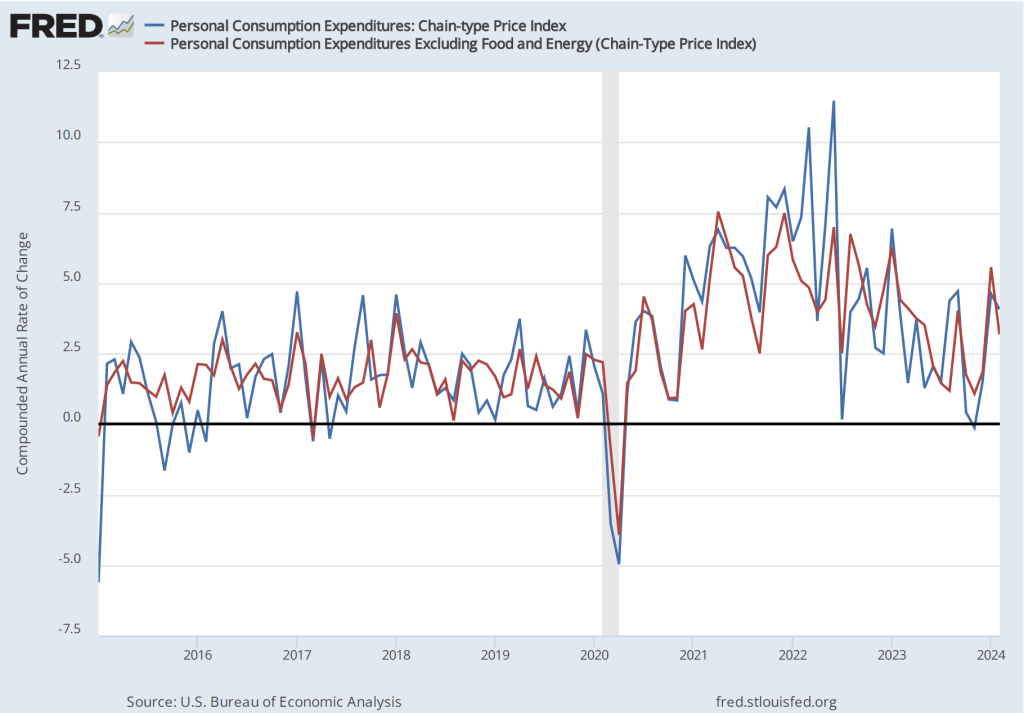

The following figure shows PCE inflation and core PCE inflation calculated by compounding the current month’s rate over an entire year. (The figure above shows what is sometimes called 12-month inflation, while this figure shows 1-month inflation.) Measured this way, both PCE inflation and core PCE inflation declined in February, but the decline only partly offset the sharp increases in December and January. Both PCE inflation—at 4.1 percent—and core PCE inflation—at 3.2 percent—remained well above the Fed’s 2 percent target.

The following figure shows another way of gauging inflation by including the 12-month inflation rate in the PCE (the same as shown in the figure above—although note that PCE inflation is now the red line rather than the blue line), inflation as measured using only the prices of the services included in the PCE (the green line), and the trimmed mean rate of PCE inflation (the blue line). Fed Chair Jerome Powell has said that he is particularly concerned by elevated rates of inflation in services. The trimmed mean measure is compiled by economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas by dropping from the PCE the goods and services that have the highest and lowest rates of inflation. It can be thought of as another way of looking at core inflation.

In February, 12-month trimmed mean PCE inflation was 3.1 percent, a little below core inflation of 3.3 percent. Twelve-month inflation in services was 3.8 percent, a slight decrease from 3.9 percent in January. Trimmed mean and services inflation tell the same story as PCE and PCE core inflation: Inflation has decline significantly from its highs of mid-2022, but remains stubbornly above the Fed’s 2 percent target.

It seems unlikely that this month’s PCE data will have much effect on when the members of the Federal Open Market Committee will decide to lower the target for the federal funds rate.

Upward Revision of 2023 Fourth Quarter Real GDP Growth May Add to Fed’s Hesitancy to Raise Fed Funds Target

(Photo courtesy of Lena Buonanno)

The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) has issued its third estimate of real GDP for the fourth quarter of 2023. The BEA now estimates that real GDP increased in the fourth quarter of 2023 at an annual rate of 3.4 percent, an increase from the BEA’s second estimate of 3.2 percent. The BEA noted that: “The update primarily reflected upward revisions to consumer spending and nonresidential fixed investment that were partly offset by a downward revision to private inventory investment.”

As the blue line in the following figure shows, despite the upward revision, fourth quarter growth in real GDP decline significantly from the very high growth rate of 4.9 percent in the third quarter. In addition, two widely followed “nowcast” estimates of real GDP growth in the first quarter of 2024 show a futher slowdown. The nowcast from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta estimates that real GDP will have grown at an annualized rate of 2.1 percent in the first quarter and the nowcast from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York estimates a growth rate of 1.9 percent. (The Atlanta Fed describes its nowcast as “a running estimate of real GDP growth based on available economic data for the current measured quarter.” The New York Fed explains: “Our model reads the flow of information from a wide range of macroeconomic data as they become available, evaluating their implications for current economic conditions; the result is a ‘nowcast’ of GDP growth ….”)

Data on growth in real gross domestic income (GDI), on the other hand, show an upward trend, as indicated by the red line in the figure. As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 8, Section 8.4 (Economics, Chapter 18, Section 18.4), gross domestic product measures the economy’s output from the production side, while gross domestic income does so from the income side. The two measures are designed to be equal, but they can differ because each measure uses different data series and the errors in data on production can differ from the errors in data on income. Economists differ on whether data on growth in real GDP or data on growth in real GDI do a better job of forecasting future changes in the economy. Accordingly, economists and policymakers will differ on how much weight to put on the fact that while the growth in real GDI had been well below growth in real GDP from the fourth quarter of 2022 to the fourth quarter of 2023, during the fourth quarter of 2023, growth in real GDI was 1.5 percentage points higher than growth in real GDP.

On balance, it seems likely that these data will reinforce the views of those members of the Fed’s policy-making Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) who were cautious about reducing the target for the federal funds rate until the macroeconomic data indicate more clearly that the economy is slowing sufficiently to ensure that inflation is returning to the Fed’s 2 percent target. In a speech on March 27 (before the latest GDP revisions became available), Fed Governor Christopher Waller reviewed the most recent macro data and concluded that:

“Adding this new data to what we saw earlier in the year reinforces my view that there is no rush to cut the [federal funds] rate. Indeed, it tells me that it is prudent to hold this rate at its current restrictive stance perhaps for longer than previously thought to help keep inflation on a sustainable trajectory toward 2 percent.”

Most other members of the FOMC appear to share Waller’s view.

Another Steady-as-She-Goes FOMC Meeting

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell (Photo from the New York Times)

As always, economists and investors had been awaiting the outcome of today’s meeting of the Federal Reserve’s policy-making Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to get further insight into future monetary policy. The expectation has been that the FOMC would begin reducing its target for the federal funds rate, mostly likely beginning with its meeting on June 11-12. Financial markets were expecting that the FOMC would make three 0.25 percentage point cuts by the end of the year, reducing its target range from the current 5.25 to 5.50 percent to 4.50 to 4.75 percent.

There appears to be nothing in the committees statement (found here) or in Powell’s press conference following the meeting to warrant a change in expectations of future Fed policy. The committee’s statement noted that: “The Committee does not expect it will be appropriate to reduce the target range until it has gained greater confidence that inflation is moving sustainably toward 2 percent.” As Powell stated in his press conference, although the committee found the general trend in inflation data to be encouraging, they would have to see additional months of data that were consistent with their 2 percent inflation target before reducing their target for the federal funds rate.

As we’ve noted in earlier blog posts (here, here, and here), inflation during January and February has been somewhat higher than expected. Some economists and investors had wondered if, as a result, the committee might delay its first cut in the federal funds target range or implement only two cuts rather than three. In his press conference, Powell seemed unconcerned about the January and February data and expected that falling inflation rates of the second half of 2023 to resume.

Typically, at the FOMC’s December, March, June, and September meetings, the committee releases a “Summary of Economic Projections” (SEP), which presents median values of the committee members’ forecasts of key economic variables.

The table shows that the committee members made relatively small changes to their projections since their December meeting. Most notable was an increase in the median projection of growth in real GDP for 2024 from 1.4 percent at the December meeting to 2.1 percent at this meeting. Correspondingly, the median projection of unemployment during 2024 dropped from 4.1 percent to 4.0 percent. The key projection of the value of the federal funds rate at the end of 2024 was left unchanged at 4.6 percent. As noted earlier, that rate is consistent with three 0.25 percent cuts in the target range during the remainder of the year.

The SEP also includes a “dot plot.” Each dot in the plot represents the projection of an individual committee member. (The committee doesn’t disclose which member is associated with which dot.) Note that there are 19 dots, representing the 7 members of the Fed’s Board of Governors and the 12 presidents of the Fed’s district banks. Although only the president of the New York Fed and the presidents of 4 of the 11 district banks are voting members of the committee, all the district bank presidents attend the committee meetings and provide economic projections.

The plots on the far left of the figure represent the projections of each of the 19 members of the value of the federal funds rate at the end of 2024. These dots are bunched fairly closely around the median projection of 4.6 percent. The dots representing the projections for 2025 and 2026 are more dispersed, representing greater uncertainty among committee members about conditions in the future. The dots on the far right represent the members’ projections of the value of the federal funds rate in the long run. As Table 1 shows, the median projected value is 2.6 percent (up slightly from 2.5 percent in December), although the plot indicates that all but one member expects that the long-run rate will be 2.5 percent or higher. In other words, few members expect a return to the very low federal funds rates of the period from 2008 to 2016.

The Latest Employment Report: How Can Total Employment and the Unemployment Rate Both Increase?

Photo courtesy of Lena Buonanno.

On the first Friday of each month, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) releases its “Employment Sitution” report for the previous month. The data for February in today’s report at first glance seem contradictory: The BLS reported that the net increase in employment in February was 275,000, which was above the increase of 200,000 that economists participating in media surveys had expected (see here and here). But the unemployment rate, which had been expected to remain constant at 3.7 percent, rose to 3.9 percent.

The apparent paradox of employment and the unemployment rate both increasing in the same month is (partly) attributable to the two numbers being from different surveys. The employment number most commonly reported in media accounts is from the establishment survey (sometimes referred to as the payroll survey), whereas the unemployment rate is taken from the household survey. The results of both surveys are included in the BLS’s monthly “Employment Situation” report. As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 9, Section 9.1 (Economics, Chapter 19, Section 19.1), many economists and policymakers at the Federal Reserve believe that employment data from the establishment survey provides a more accurate indicator of the state of the labor market than do either the employment data or the unemployment data from the household survey. Accordingly, most media accounts interpreted the data released today as indicating continuing strength in the labor market.

However, it can be worth looking more closely at the differences between the measures of employment in the two series because it’s possible that the household survey data is signalling that the labor market is weaker than it appears from the establishment survey data. The following table shows the data on employment from the two surveys for January and February.

| Establishment Survey | Household Survey | |

| January | 157,533,000 | 161,152,000 |

| February | 157,808,000 | 160,968,000 |

| Change | +275,000 | -184,000 |

Note that in addition to the fact that employment as measured by the household survey is falling, while employment as measured by the establishment survey is increasing, household survey employment is significantly higher in both months. Household survey employment is always higher than establishment survey employment because the household survey includes employment of three groups that are not included in the establishment survey:

- Self-employed workers

- Unpaid family workers

- Agricultural workers

(A more complete discuss of the differences in employment in the two surveys can be found here.) The BLS also publishes a useful data series in which it attempts to adjust the household survey data to more closely mirror the establishment survey data by, among other adjustments, removing from the household survey categories of workers who aren’t included in the payroll survey. The following figure shows three series—the establishment series (gray line), the reported household series (orange line), and the adjusted household series (blue line)—for the months since 2021. For ease of comparison the three series have been converted to index numbers with January 2021 set equal to 100.

Note that for most of this period, the adjusted household survey series tracks the establishment survey series fairly closely. But in November 2023, both household survey measures of employment begin to fall, while the establishment survey measure of employment continues to increase. Falling employment in the household survey may be signalling weakness in the labor market that employment in the establishment survey may be missing, but it might also be attributed to the greater noisiness in the household survey’s employment data.

There are three other things to note in this month’s employment report. First, the BLS revised the initially reported increase in December establishement survey employment downward by 35,000 jobs and the January increase downward by 124,000 jobs. The January adjustment was large—amounting to more than 35 percent of the initially reported increase of 353,000. It’s normal for the BLS to revise its initial estimates of employment from the establishment survey but a series of negative revisions is typical of periods just before or at the beginning of a recession. It’s important to note, though, that several months of negative revisions to establishment employment are far from an infallible predictor of recessions.

Second, as shown in the following figure, the increase in average hourly earnings slowed from the high rate of 6.8 percent in January to 1.7 percent in February—the smallest increase since early 2022.. (These increases are measured at a compounded annual rate, which is the rate wages would increase if they increased at that month’s rate for an entire year.) A slowing in wage growth may be another sign that the labor market is weakening, although the data are noisy on a month-to-month basis.

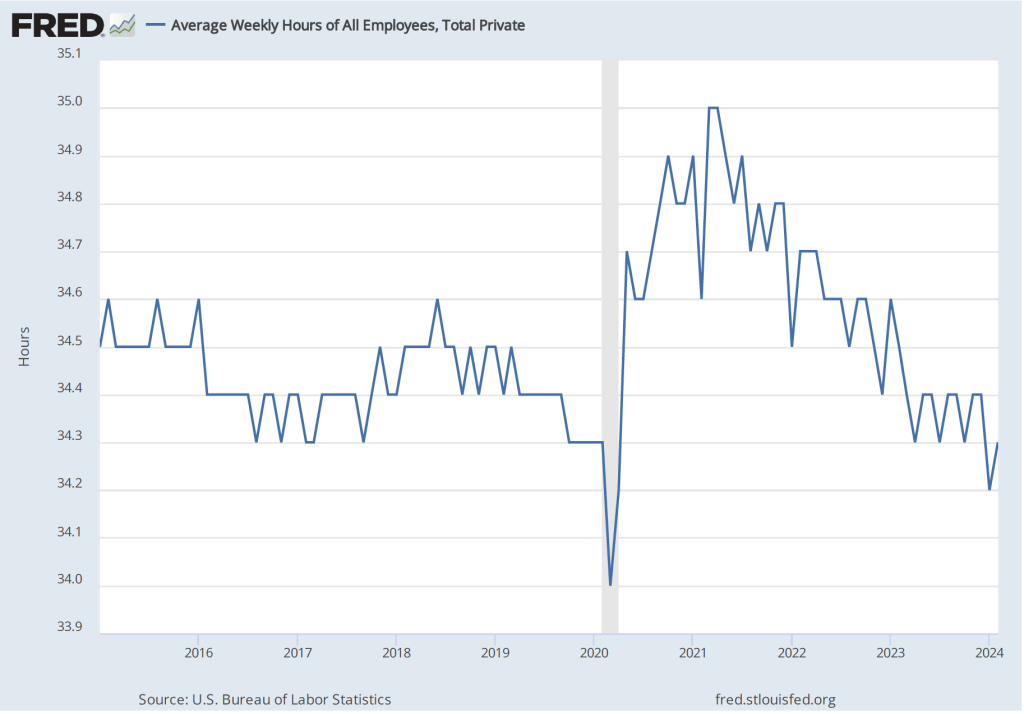

Finally, one positive indicator of the state of the labor market is that average weekly hours worked increased. As shown in the following figure, average hours worked had been slowly, if irregularly, trending downward since early 2021. In February, average hours worked increased slightly to 34.3 hours per week from 34.2 hours per week in January. But, again, it’s difficult to draw strong conclusions from one month’s data.

In testifying before Congress earlier this week, Fed Chair Jerome Powell noted that:

“We believe that our policy rate [the federal funds rate] is likely at its peak for this tightening cycle. If the economy evolves broadly as expected, it will likely be appropriate to begin dialing back policy restraint at some point this year. But the economic outlook is uncertain, and ongoing progress toward our 2 percent inflation objective is not assured.”

It seems unlikely that today’s employment report will change how Powell and the other memebers of the Fed’s Federal Open Market Committee evaluate the current economic situation.

The Latest PCE Report and PCE Inflation v. CPI Inflation

Photo courtesy of Lena Buonanno.

Wall Street Journal columnist Justin Lahart notes that when the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) releases its monthly report on the consumer price index (CPI), the report “generates headlines, features in politicians’ speeches and moves markets.” When the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) releases its monthly report “Personal Income and Outlays,” which includes data on the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index, there is much less notice in the business press or, often, less effect on financial markets. (You can see the difference in press coverage by comparing the front page of today’s online edition of the Wall Street Journal after the BEA released the latest PCE data with the paper’s front page on February 13 when the BLS released the latest CPI data.)

This difference in the weight given to the two inflation reports seems curious because the Federal Reserve uses the PCE, not the CPI, to determine whether it is achieving its 2 percent annual inflation target. When a new monthly measure of inflation is released much of the discussion in the media is about the effect the new data will have on the Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) decision on whether to change its target for the federal funds rate. You might think the result would be greater media coverage of the PCE than the CPI. (The PCE includes the prices of all the goods and services included in the consumption component of GDP. Because the PCE includes the prices of more goods and services than does the CPI, it’s a broader measure of inflation, which is the key reason that the Fed prefers it.)

That CPI inflation data receive more media discussion than PCE inflation data is likely due to three factors:

- The CPI is more familiar to most people than the PCE. It is also the measure that politicians and political commentators tend to focus on. The media are more likely to highlight a measure of inflation that the average reader easily understands rather than a less familiar measure that would require an explanation.

- The monthly report on the CPI is typically released about two weeks before the monthly report on the PCE. Therefore, if the CPI measure of inflation turns out to be higher or lower than expected, the stock and bond markets will react to this new information on the value of inflation in the previous month. If the PCE measure is roughly consistent with the CPI measure, then the release of new data on the PCE measure contains less new information and, therefore, has a smaller effect on stock and bond prices.

- Over longer periods, the two measures of inflation often move fairly closely together as the following figure shows, although CPI inflation tends to be somewhat higher than PCE inflation. The values of both series are the percentage change in the index from the same month in the previous year.

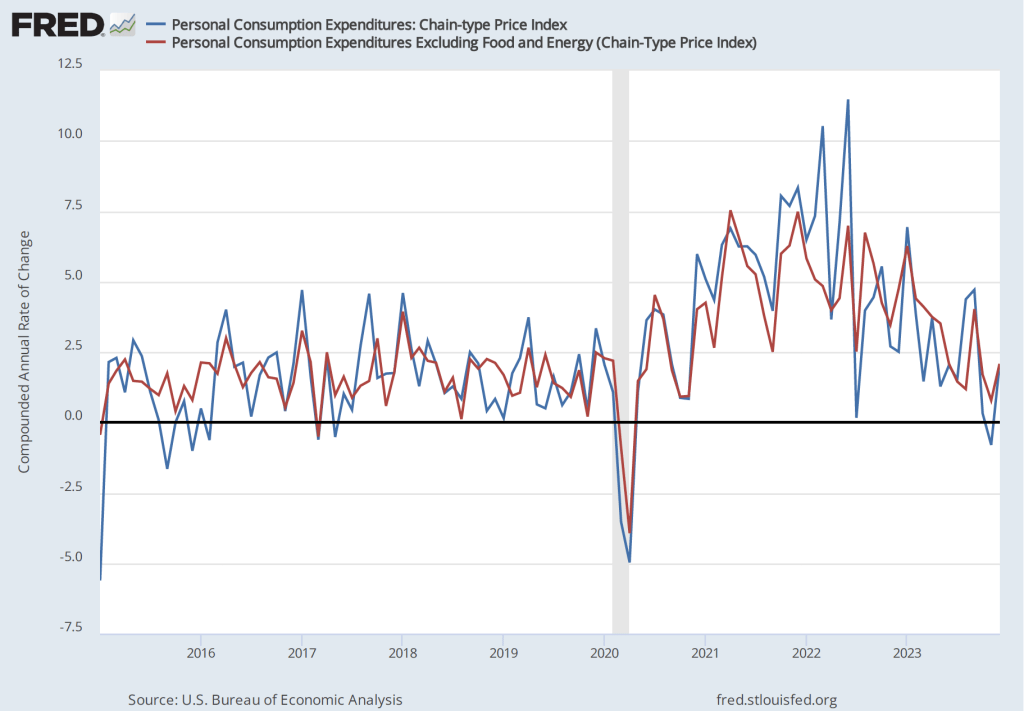

Turning to the PCE data for January released in the BEA’s latest “Personal Income and Outlays” report, the PCE inflation data were broadly consistent with the CPI data: Inflation in January increased somewhat from December. The first of the following figures shows PCE inflation and core PCE inflation—which excludes energy and food prices—for the period since January 2015 with inflation measured as the change in PCE from the same month in the previous year. The second figure shows PCE inflation and core PCE inflation measured as the inflation rate calculated by compounding the current month’s rate over an entire year. (The first figure shows what is sometimes called 12-month inflation and the second figure shows 1-month inflation.)

The two inflation measures are telling markedly different stories: 12-month inflation shows a continuation in the decline in inflation that began in 2022. Twelve-month PCE inflation fell from 2.6 percent in December to 2.4 percent in January. Twelve-month core PCE inflation fell from 2.9 percent in December to 2.8 percent in December. So, by this measure, inflation continues to approach the Fed’s 2 percent inflation target.

One-month PCE and core PCE inflation both show sharp increases from December to January: From 1.4 percent in December to 4.2 percent for 1-month PCE inflation and from 1.8 percent in December to 5.1 percent in January for 1-month core PCE inflation.

The one-month inflation data are bad news in that they may indicate that inflation accelerated in January and that the Fed is, therefore, further away than it seemed in December from hitting its 2 percent inflation target. But it’s important not to overinterpret a single month’s data. Although 1-month inflation is more volatile than 12-month inflation, the broad trend in 1-month inflation had been downwards from mid-2022 through December 2023. It will take at least a more months of data to assess whether this trend has been broken.

Fed officials didn’t appear to be particularly concerned by the news. For instance, according to an article on bloomberg.com, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta President Raphael Bostic noted that: “The last few inflation readings—one came out today—have shown that this is not going to be an inexorable march that gets you immediately to 2%, but that rather there are going to be some bumps along the way.” Investors appear to continue to expect that the Fed will cut its target for the federal funds rate at its meeting on June 11-12.

Surprisingly Strong CPI Report

Photo courtesy of Lena Buonanno.

As we’ve discussed in several blog posts (for instance, here and here), recent macro data have been consistent with the Federal Reserve being close to achieving a soft landing. The Fed’s increases in its target for the federal funds rate have slowed the growth of aggregate demand sufficiently to bring inflation closer to the Fed’s 2 percent target, but haven’t, to this point, slowed the growth of aggregate demand so much that the U.S. economy has been pushed into a recession.

By January 2024, many investors in financial markets and some economists were expecting that at its meeting on March 19-20, the Fed’s Federal Open Market Committee would be cutting its target for the federal funds. However, members of the committee—notably, Chair Jerome Powell—have been cautious about assuming prematurely that inflation had, in fact, been brought under control. In fact, in his press conference on January 31, following the committee’s most recent meeting, Powell made clear that the committee was unlikely to reduce its target for the federal funds rate at its March meeting. Powell noted that “inflation is still too high, ongoing progress in bringing it down is not assured, and the path forward is uncertain.”

Powell’s caution seemed justified when, on February 2, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released its most recent “Employment Situation Report” (discussed in this post). The report’s data on growth in employment and growth in wages, as measured by the change in average hourly earnings, might be indicating that aggregate demand is growing too rapidly for inflation to continue to decline.

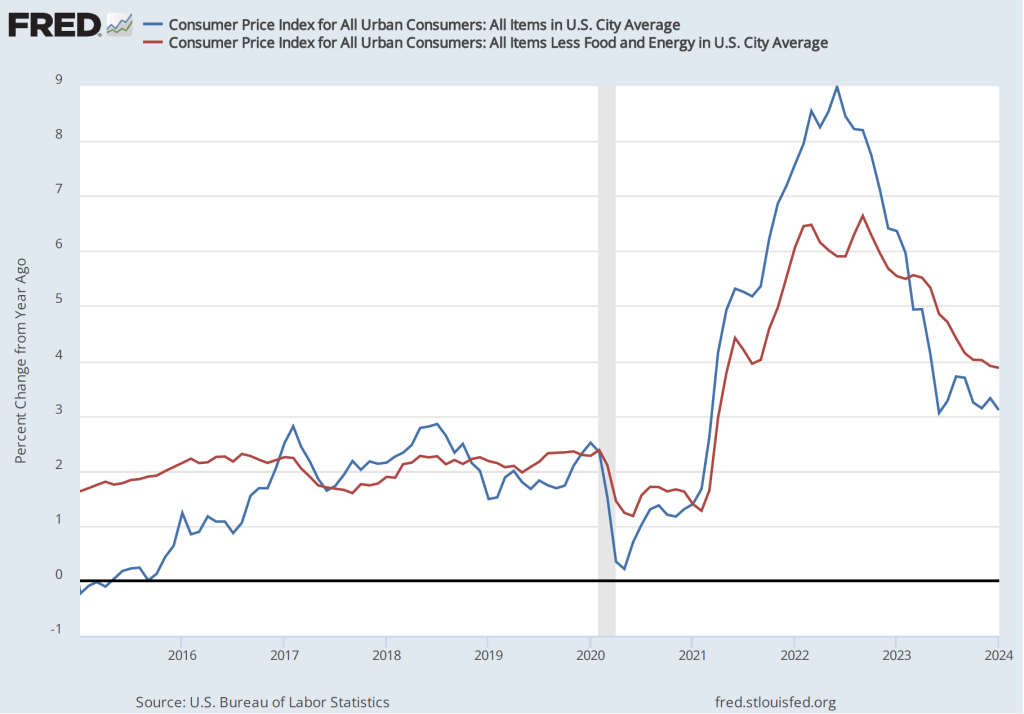

The BLS’s release today (February 13) of its report on the consumer price index (CPI) (found here) for January provided additional evidence that the Fed may not yet have put inflation on a firm path back to its 2 percent target. The average forecast of economists surveyed before the release of the report was that the increase in the version of the CPI that includes the prices of all goods and services in the market basket—often called headline inflation—would be 2.9 percent. (We discuss how the BLS constructs the CPI in Macroeconomics, Chapter 9, Section 19.4, Economics, Chapter 19, Section 19.4, and Essentials of Economics, Chapter 3, Section 13.4.) As the following figure shows, headline inflation for January was higher than expected at 3.1 percent (measured by the percentage change from the same month in the previous year), while core inflation—which excludes the prices of food and energy—was 3.9 percent. Headline inflation was lower than in December 2023, while core inflation was almost unchanged.

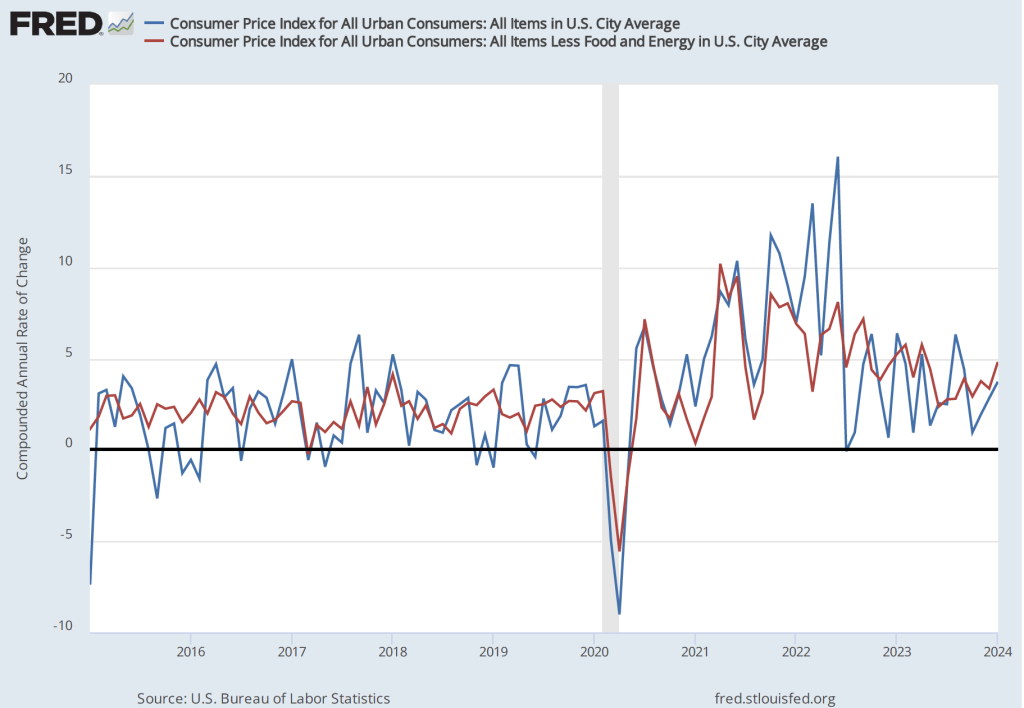

Although the values for January might seem consistent with a gradual decline in inflation, that conclusion may be misleading. Headline inflation in January 2023 had been surprisingly high at 6.4 percent. Hence, the comparision between the value of the CPI in January 2024 with the value in January 2023 may be making the annual CPI inflation rate seem artificially low. If we look at the 1-month inflation rate for headline and core inflation—that is the annual inflation rate calculated by compounding the current month’s rate over an entire year—the values are more concerning, as indicated in the following figure. Headline CPI inflation is 3.7 percent and core CPI inflation is 4.8 percent.

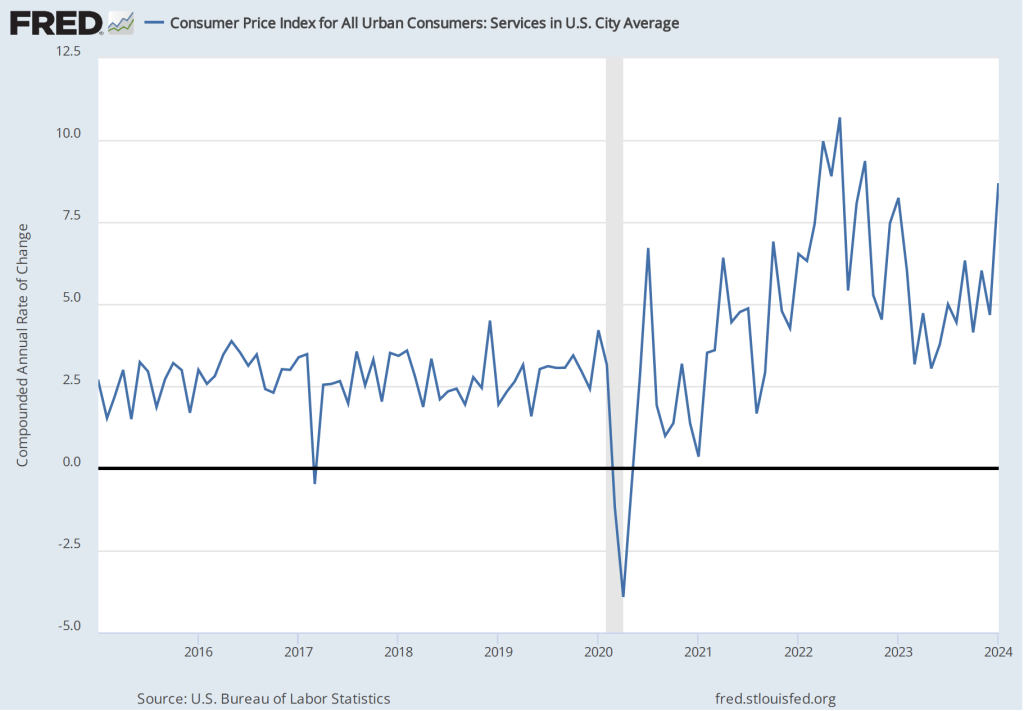

Even more concerning is the path of inflation in the prices of services. Chair Powell has emphasized that as supply chain problems have gradually been resolved, inflation in the prices of goods has been rapidly declining. But inflaion in services hasn’t declined nearly as much. Last summer he stated the point this way:

“Part of the reason for the modest decline of nonhousing services inflation so far is that many of these services were less affected by global supply chain bottlenecks and are generally thought to be less interest sensitive than other sectors such as housing or durable goods. Production of these services is also relatively labor intensive, and the labor market remains tight. Given the size of this sector, some further progress here will be essential to restoring price stability.”

The following figure shows the 1-month inflation rate in services prices. The figure shows that inflation in services has been above 4 percent in every month since July 2023. Inflation in services was a very high 8.7 percent in January. Clearly such large increases in the prices of services aren’t consistent with the Fed meeting its 2 percent inflation target.

How should we interpret the latest CPI report? First, it’s worth bearing in mind that a single month’s report shouldn’t be relied on too heavily. There can be a lot of volatility in the data month-to-month. For instance, inflation in the prices of services jumped from 4.7 percent in December to 8.7 percent in January. It seems unlikely that inflation in the prices of services will continue to be over 8 percent.

Second, housing prices are a large component of service prices and housing prices can be difficult to measure accurately. Notably, the BLS includes in its measure the implicit rental price that someone who owns his or her own home pays. The BLS calculates that implict rental price by asking consumers who own their own homes the following question: “If someone were to rent your home today, how much do you think it would rent for monthly, unfurnished and without utilities?” (The BLS discusses how it measures the price of housing services here.) In practice, it may be difficult for consumers to accurately answer the question if very few houses similar to theirs are currently for rent in their neighborhood.

Third, the Fed uses the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index, not the CPI, to gauge whether it is achieving its 2 percent inflation target. The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) includes the prices of more goods and services in the PCE than the BLS includes in the CPI and measures housing services using a different approach than that used by the BLS. Although inflation as measured by changes in the CPI and as measured by changes in the PCE move roughly together over long periods, the two measures can differ significantly over a period of a few months. The difference between the two inflation measures is another reason not to rely too heavily on a single month’s CPI data.

Despite these points, investors on Wall Street clearly interpreted the CPI report as bad news. Investors have been expecting that the Fed will soon cut its target for the federal funds rate, which should lead to declines in other key interest rates. If inflation continues to run well above the Fed’s 2 percent target, it seems likely that the Fed will keep its federal funds target at its current level for longer, thereby slowing the growth of aggregate demand and raising the risk of a recession later this year. Accordingly, the Dow Jones Industrial Average declined by more than 500 points today (February 13) and the interest rate on the 10-year Treasury note rose above 4.3 percent.

The FOMC has more than a month before its next meeting to consider the implications of the latest CPI report and the additional macro data that will be released in the meantime.

Surprisingly Strong Jobs Report

Photo courtesy of Lena Buonanno.

This morning of Friday, February 2, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) issued its “Employment Situation Report” for January 2024. Economists and policymakers—notably including the members of the Fed’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC)—typically focus on the change in total nonfarm payroll employment as recorded in the establishment, or payroll, survey. That number gives what is generally considered to be the best gauge of the current state of the labor market.

Economists surveyed in the past few days by business news outlets had expected that growth in payroll employment would slow to an increase of between 180,000 and 190,000 from the increase in December, which the BLS had an initially estimated as 216,00. (For examples of employment forecasts, see here and here.) Instead, the report indicated that net employment had increased by 353,000—nearly twice the expected amount. (The full report can be found here.)

In this previous blog post on the December employment report, we noted that although the net increase in employment in that month was still well above the increase of 70,000 to 100,000 new jobs needed to keep up with population growth, employment increases had slowed significantly in the second half of 2023 when compared with the first.

That slowing trend in employment growth did not persist in the latest monthly report. In addition, to the strong January increase of 353,000 jobs, the November 2023 estimate was revised upward from 173,000 jobs to 182,000 jobs, and the December estimate was substantially revised from 216,000 to 333,000. As the following figure from the report shows, the net increase in jobs now appears to have trended upward during the last three months of 2023.

Economists surveyed were also expecting that the unemployment rate—calculated by the BLS from data gathered in the household survey—would increase slightly to 3.8 percent. Instead, it remained constant at 3.7 percent. As the following figure shows, the unemployment rate has been remarkably stable for more than two years and has been below 4.0 percent each month since December 2021. The members of the FOMC expect that the unemployment rate during 2024 will be 4.1 percent, a forcast that will be correct only if the demand for labor declines significantly over the rest of the year.

The “Employment Situation Report” also presents data on wages, as measured by average hourly earnings. The growth rate of average hourly earnings, measured as the percentage change from the same month in the previous year, had been slowly declining from March 2022 to October 2023, but has trended upward during the past few months. The growth of average hourly earnings in January 2024 was 4.5 percent, which represents a rise in firms’ labor costs that is likely too high to be consistent with the Fed succeeding in hitting its goal of 2 percent inflation. (Keep in mind, though, as we note in this blog post, changes in average hourly earnings have shortcomings as a measure of changes in the costs of labor to businesses.)

Taken together, the data in today’s “Employment Situation Report” indicate that the U.S. labor market remains very strong. One implication is that the FOMC will almost certainly not cut its target for the federal funds rate at its next meeting on March 19-20. As Fed Chair Jerome Powell noted in a statement to reporters after the FOMC earlier this week: “The Committee does not expect it will be appropriate to reduce the target range until it has gained greater confidence that inflation is moving sustainably toward 2 percent. We will continue to make our decisions meeting by meeting.” (A transcript of Powell’s press conference can be found here.) Today’s employment report indicates that conditions in the labor market may not be consistent with a further decline in price inflation.

It’s worth keeping several things in mind when interpreting today’s report.

- The payroll employment data and the data on average hourly earnings are subject to substantial revisions. This fact was shown in today’s report by the large upward revision in net employment creation in December, as noted earlier in this post.

- A related point: The data reported in this post are all seasonally adjusted, which means that the BLS has revised the raw (non-seasonally adjusted) data to take into account normal fluctuations due to seasonal factors. In particular, employment typically increases substantially during November and December in advance of the holiday season and then declines in January. The BLS attempts to take into account this pattern so that it reports data that show changes in employment during these months holding constant the normal seasonal changes. So, for instance, the raw (non-seasonally adjusted) data show a decrease in payroll employment during January of 2,635,000 as opposed to the seasonally adjusted increase of 353,000. Over time, the BLS revises these seasonal adjustment factors, thereby also revising the seasonally adjusted data. In other words, the BLS’s initial estimates of changes in payroll employment for these months at the end of one year and the beginning of the next should be treated with particular caution.

- The establishment survey data on average weekly hours worked show a slow decline since November 2023. Typically, a decline in hours worked is an indication of a weakening labor market rather than the strong labor market indicated by the increase in employment. But as the following figure shows, the data on average weekly hours are noisy in that the fluctuations are relatively large, as are the revisons the BLS makes to these data over time.

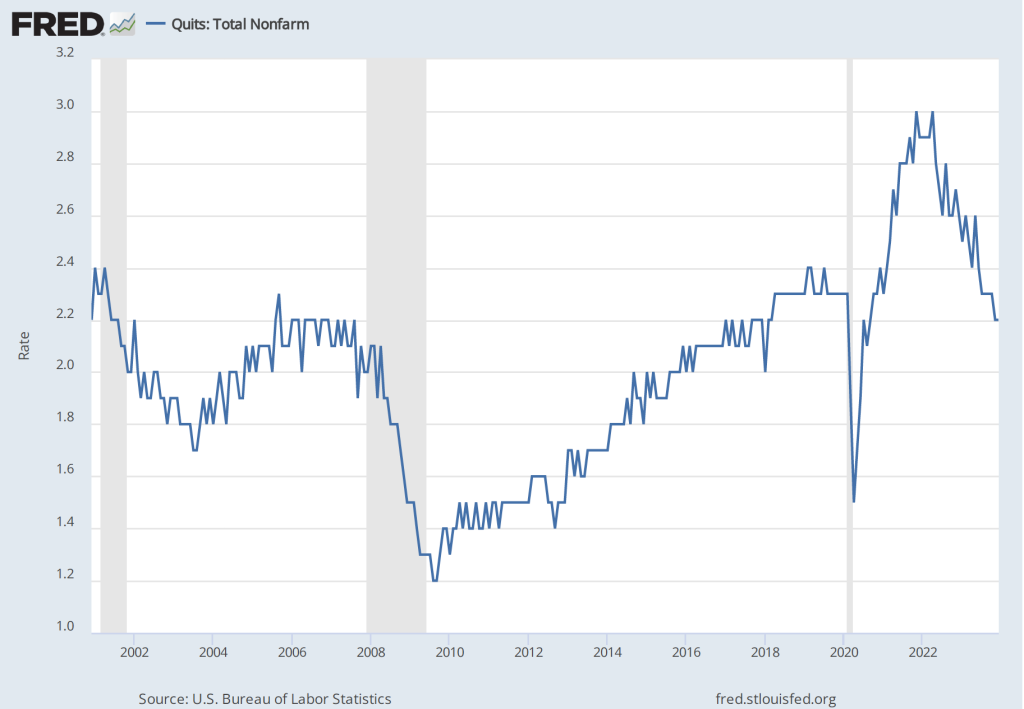

4. In contrast to today’s jobs report, other labor market data seem to indicate that the demand for labor is slowing. For instance, quit rates—or the number of people voluntarily leaving their jobs as a percentage of the total number of people employed—have been declining. As shown in the following figure, the quit rate peaked at 3.0 percent in November 2021 and March 2022, and has declined to 2.2 percent in December 2023—a rate lower than just before the beginning of the Covid–19 pandemic.

Similarly, as the following figure shows, the number of job openings per unemployed person has declined from a high of 2.0 in March 2022 to 1.4 in December 2023. This value is still somewhat higher than just before the beginning of the Covid–19 pandemic.

To summarize, recent data on conditions in the labor market have been somewhat mixed. The strong increases in net employment and in average hourly earnings in recent months are in contrast with declining average number of hours worked, a declining quit rate, and a falling number of job openings per unemployed person. Taken together, these data make it likely that the FOMC will be in no hurry to cut its target for the federal funds rate. As a result, long-term interest rates are also likely to remain high in the coming months. The following figure from the Wall Street Journal provides a striking illustration of the effect of today’s jobs report on the bond market, as the interest rate on the 10-year Treasury note rose above 4.0 percent for the first time in more than a month. The interest rate on the 10-year Treasury note plays an important role in the financial system, influencing interest rates on mortgages and corporate bonds.

FOMC Meeting: Steady as She Goes

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell (Photo from the New York Times.)

This afternoon, Wednesday, January 31, the Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) held the first of its eight scheduled meetings during 2024. As we noted in a recent post, macroeconomic data have been indicating that the Fed is close to achieving its goal of bringing the U.S. economy in for a soft landing—reducing inflation down to the Fed’s 2 percent target without pushing the economy into a recession. But as we also noted in that post, it was unlikely that at this meeting Fed Chair Jerome Powell and the other members of the FOMC would declare victory in their fight to reduce inflation from the high levels it reached during 2022.

In fact, in Powell’s press conference following the meeting, when asked directly by a reporter whether he believed that the economy had made a safe landing, Powell said that he wasn’t yet willing to draw that conclusion. Accordingly, the committee kept its target range for the federal funds rate unchanged at 5.25 percent to 5.50 percent. This was the fifth meeting in a row at which the FOMC had left the target unchanged. Although some policy analysts expect that the FOMC might reduce its federal funds rate target at its next meeting in March, the committee’s policy statement made that seem unlikely:

“In considering any adjustments to the target range for the federal funds rate, the Committee will carefully assess incoming data, the evolving outlook, and the balance of risks. The Committee does not expect it will be appropriate to reduce the target range until it has gained greater confidence that inflation is moving sustainably toward 2 percent.”

Powell reinforced the point during his press conference by stating it was unlikely that the committee would cut the target rate at the next meeting. He noted that:

“The economy has surprised forecasters in many ways since the pandemic, and ongoing progress toward our 2 percent inflation objective is not assured. The economic outlook is uncertain, and we remain highly attentive to inflation risks. We are prepared to maintain the current target range for the federal funds rate for longer, if appropriate.”

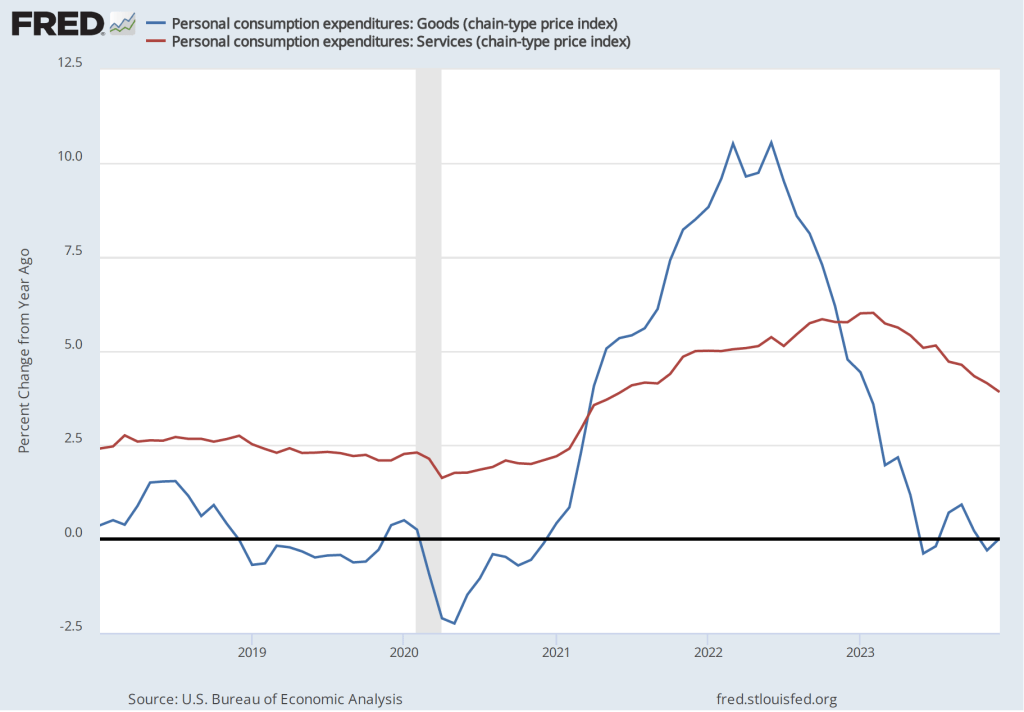

Powell highlighted a couple of areas of potential concern. The Fed gauges its progress towards achieving its 2 percent inflation goal using the percentage change in the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index. As we noted in a recent post, PCE inflation has declined from a high of 7.1 percent in June 2022 to 2.9 percent in December 2023. But Powell noted that PCE inflation in goods has followed a different path from PCE inflation in services, as the following figure shows.

Inflation during 2022 was much greater in the prices of goods than in the prices of services, reflecting the fact that supply chain disruptions caused by the pandemic had a greater effect on goods than on services. Inflation in goods has been less than 1 percent every month since June 2023 and has been negative in three of those months. Inflation in services peaked in February 2023 at 6.0 percent and has been declining since, but was still 3.9 percent in December. Powell noted that the very low rates of inflation in the prices of goods probably aren’t sustainable. If inflation in the prices of goods increases, the Fed may have difficulty achieving its 2 percent inflation target unless inflation in the prices of services slows.

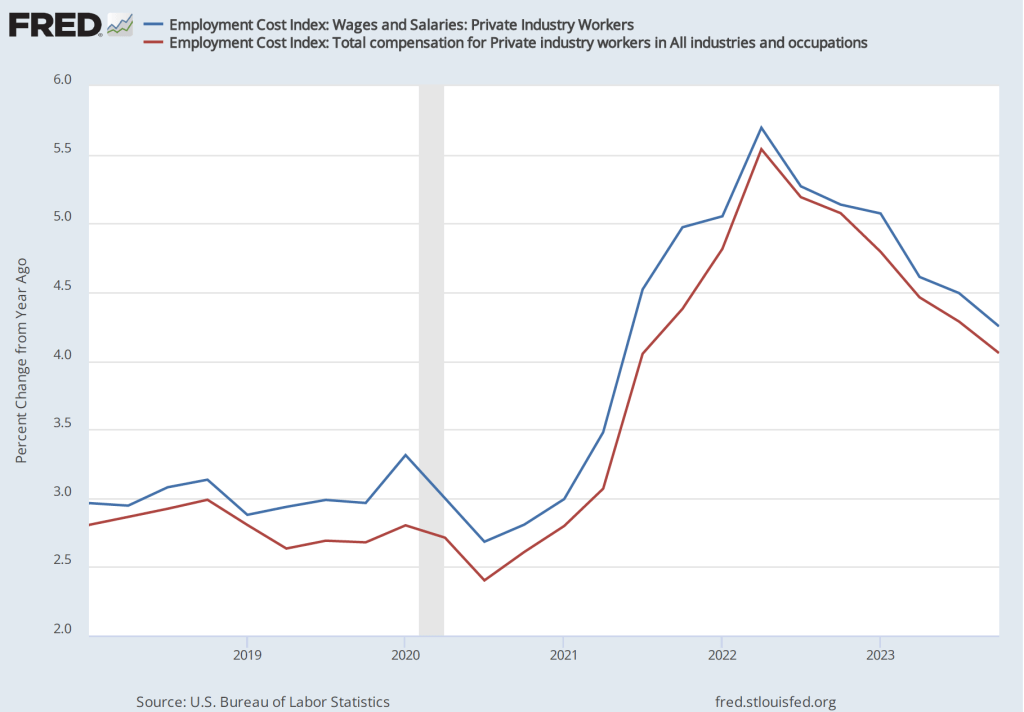

Powell also noted that the most recent data on the employment cost index (ECI) had been released the morning of the meeting. The ECI is compiled by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and is published quarterly. It measures the cost to employers per employee hour worked. The BLS publishes data that includes only wages and salaries and data that includes, in addition to wages and salaries, non-wage benefits—such as contributions to retirement accounts or health insurance—that firms pay workers. The figure below shows the percentage change from the same month in the previous year for the ECI including just wages and salaries (blue line) and for the ECI including all compensation (red line). Although ECI inflation has declined significantly from its peak in he second quarter of 2022, in the fourth quarter of 2023, both measures of ECI inflation were above 4 percent. Wages increasing at that pace may not be consistent with a 2 percent rate of price inflation.

Powell’s tone at his news conference (which can be watched here) was one of cautious optimism. He and the other committee members expect to be able to cut the target for the federal funds rate later this year but remain on guard for any indications that the inflation rate is increasing again.

Has the Federal Reserve Achieved a Soft Landing?

The Federal Reserve building in Washington, DC. (Photo from the New York Times.)

Since inflation began to increase rapidly in the late spring of 2021, the key macroeconomic question has been whether the Fed would be able to achieve a soft landing—pushing inflation back to its 2 percent target without causing a recession. The majority of the members of the Fed’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) believed that increases in inflation during 2021 were largely caused by problems with supply chains resulting from the effects of the Covid–19 pandemic.

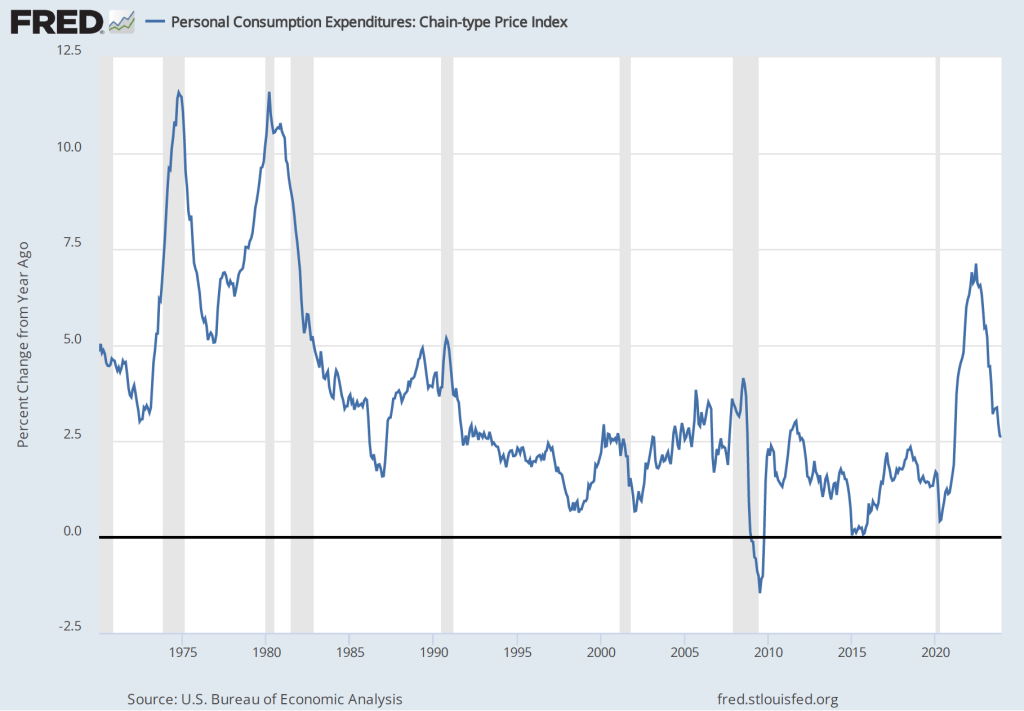

These committee members believed that once supply chains returned to normal, the increase in he inflation rate would prove to have been transitory—meaning that the inflation rate would decline without the need for the FOMC to pursue a contractionary monetary by substantially raising its target range for the federal funds rate. Accordingly, the FOMC left its target range unchanged at 0 to 0.25 percent until March 2022. As the following figure shows, by that time the inflation rate had increased to 6.9 percent, the highest it had been since January 1982. (Note that the figure shows inflation as measured by the percentage change from the same month in the previous year in the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index. Inflation as measured by the PCE is the gauge the Fed uses to determine whether it is achieving its goal of 2 percent inflation.)

By the time inflation reached its peak in mid-2022, many economists believed that the FOMC’s decision to delay increasing the federal funds rate until March 2022 had made it unlikely that the Fed could return inflation to 2 percent without causing a recession. But the latest macroeconomic data indicate that—contrary to that expectation—the Fed does appear to have come very close to achieving a soft landing. On January 26, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) released data on the PCE for December 2023. The following figure shows for the period since 2015, inflation as measured by the percentage change in the PCE from the same month in the previous year (the blue line) and as measured by the percentage change in the core PCE, which excludes the prices of food and energy (the red line).

The figure shows that PCE inflation continued its decline, falling slightly in December to 2.6 percent. Core PCE inflation also declined in December to 2.9 percent from 3.2 percent in November. Note that both measures remained somewhat above the Fed’s inflation target of 2 percent.

If we look at the 1-month inflation rate—that is the annual inflation rate calculated by compounding the current month’s rate over an entire year—inflation is closer to Fed’s target, as the following figure shows. The 1-month PCE inflation rate has moved somewhat erratically, but has generally trended down since mid-2022. In December, PCE inflation increased from from –0.8 percent in November (which acutally indicates that deflation occurred that month) to 2.0 percent in December. The 1-month core PCE inflation rate has moved less erratically, also trending down since mid-2022. In December, the 1-month core PCE inflation increased from 0.8 percent in November to 2.1 percent in December. In other words, the December reading on inflation indicates that inflation is very close to the Fed’s target.

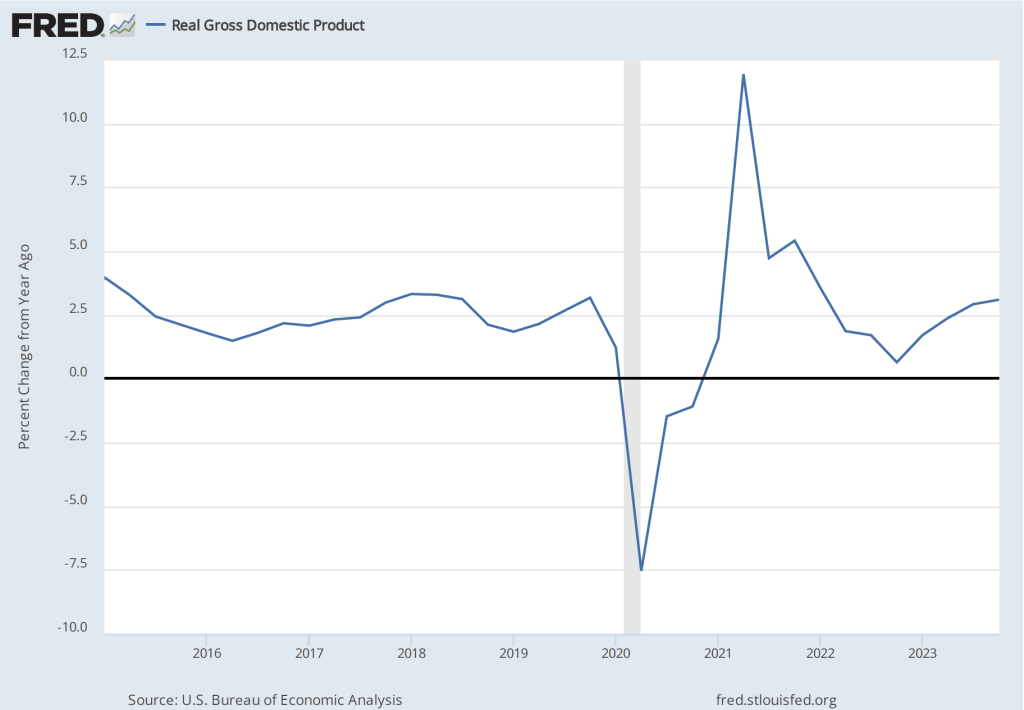

The following figure shows for each quarter since the beginning of 2015, the growth rate of real GDP measured as the percentage change from the same quarter in the previous year. The figure indicates that although real GDP growth dropped to below 1 percent in the fourth quarter of 2022, the growth rate rose during each quarter of 2023. The growth rate of 3.1 percent in the fourth quarter of 2023 remained well above the FOMC’s 1.8 percent estimate of long-run economic growth. (The average of the members of the FOMC’s estimates of the long-run growth rate of real GDP can be found here.) To this point, there is no indication from the GDP data that the U.S. economy is in danger of experiencing a recession in the near future.

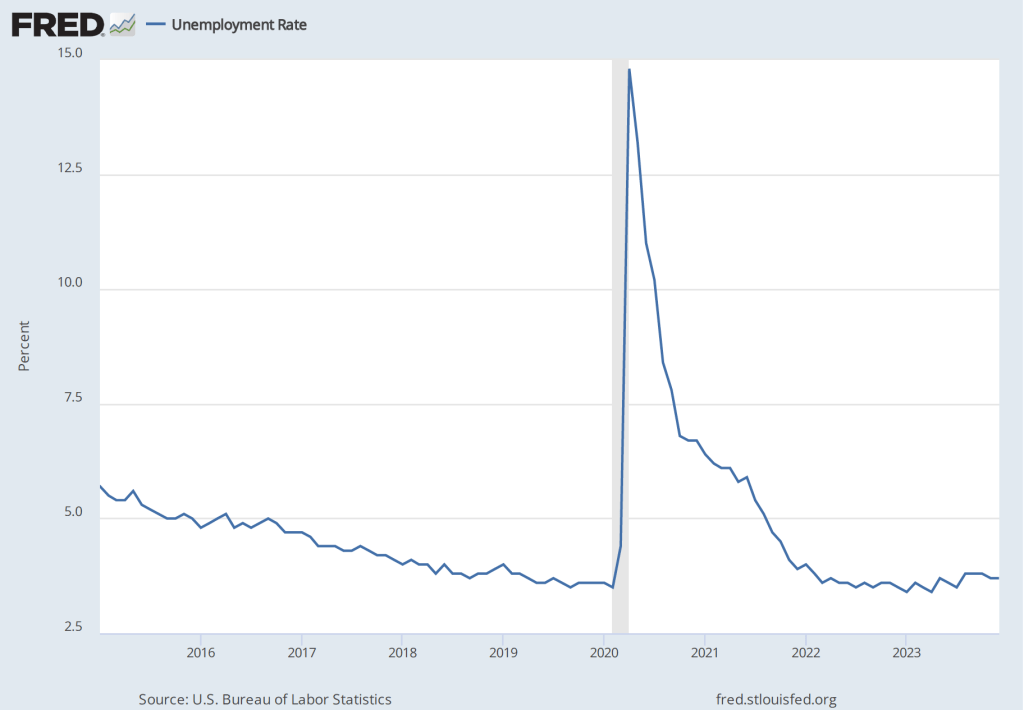

The labor market also shows few signs of a recession, as indicated by the following figure, which shows the unemployment rate in the months since January 2015. The unemployment rate has remained below 4 percent in each month since December 2021. The unemployment rate was 3.7 percent in December 2023, below the FOMC’s projection of a long-run unemployment rate of 4.1 percent.

The FOMC’s next meeting is on Tuesday and Wednesday of this week (February 1-2). Should we expect that at that meeting Fed Chair Jerome Powell will declare that the Fed has succeeded in achieving a soft landing? That seems unlikely. Powell and the other members of the committee have made clear that they will be cautious in interpreting the most recent macroeconomic data. With the growth rate of real GDP remaining above its long run trend and the unemployment rate remaining below most estimates of the natural rate of unemployment, there is still the potential that aggregate demand will increase at a rate that might cause the inflation rate to once again rise.

In a speech at the Brookings Institution on January 16, Fed Governor Christopher Waller echoed what appear to be the views of most members of the FOMC:

“Time will tell whether inflation can be sustained on its recent path and allow us to conclude that we have achieved the FOMC’s price-stability goal. Time will tell if this can happen while the labor market still performs above expectations. The data we have received the last few months is allowing the Committee to consider cutting the policy rate in 2024. However, concerns about the sustainability of these data trends requires changes in the path of policy to be carefully calibrated and not rushed. In the end, I am feeling more confident that the economy can continue along its current trajectory.”

At his press conference on February 1, following the FOMC meeting, Chair Powell will likely provide more insight into the committee’s current thinking.