Image generated by ChatGPT 5

In June, the U.S. Census Bureau released its population estimates for 2024. Included was the following graphic showing the change in the U.S. population pyramid from 2004 to 2024. As the graphic shows, people 65 years and older have increased as a fraction of the total population, while children have decreased as a fraction of the total population. (The Census considers everyone 17 and younger to be a child.) Between 2004 and 2024, people 65 and older increased from 12.4 percent of the population to 18.0 percent. People younger than 18 fell from 25.0 percent of the population in 2004 to 21.5 percent in 2024.

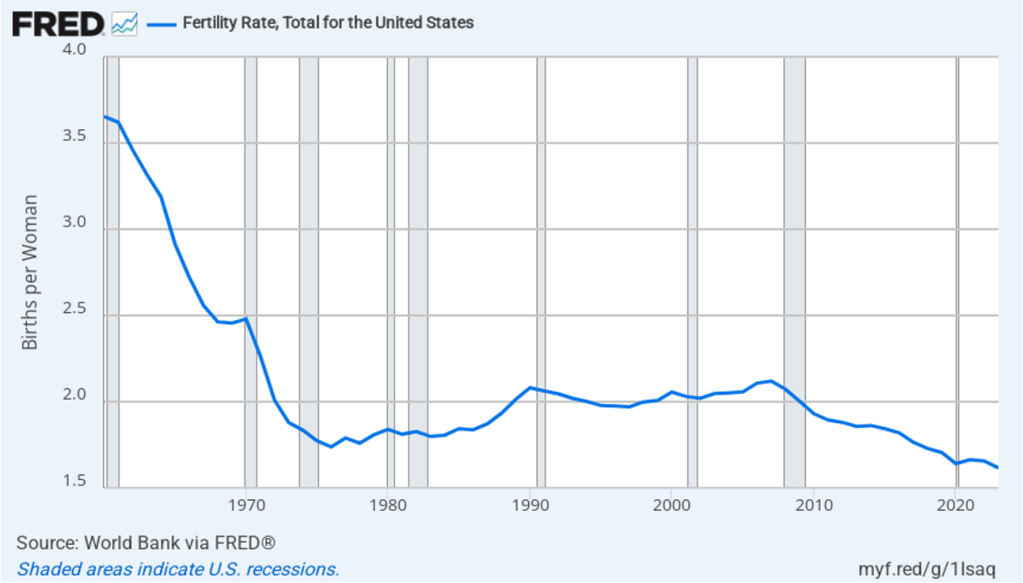

The aging of the U.S. population reflects falling birth rates. Demographers and economists typically measure birth rates as the total fertility rate (TFR), which is defined by the World Bank as: “The number of children that would be born to a woman if she were to live to the end of her childbearing years and bear children in accordance with age-specific fertility rates currently observed.” The TFR has the advantage over the simple birth rate—which is the number of live births per thousand people—because the TFR corrects for the age structure of a country’s female population. Leaving aside the effects of immigration and emigration, a TFR of 2.1 is necessary to keep a country’s population stable. Stated another way, a country needs a TFR of 2.1 to achieve replacement level fertility. A country with a TFR above 2.1 experiences long-run population growth, while a country with a TFR of less than 2.1 experiences long-run population decline.

The following figure shows the TFR for the United States for each year between 1960 and 2023. Since 1971, the TFR has been below 2.1 in every year except for 2006 and 2007. Immigration has helped to offset the effects on population growth of a TFR below 2.1.

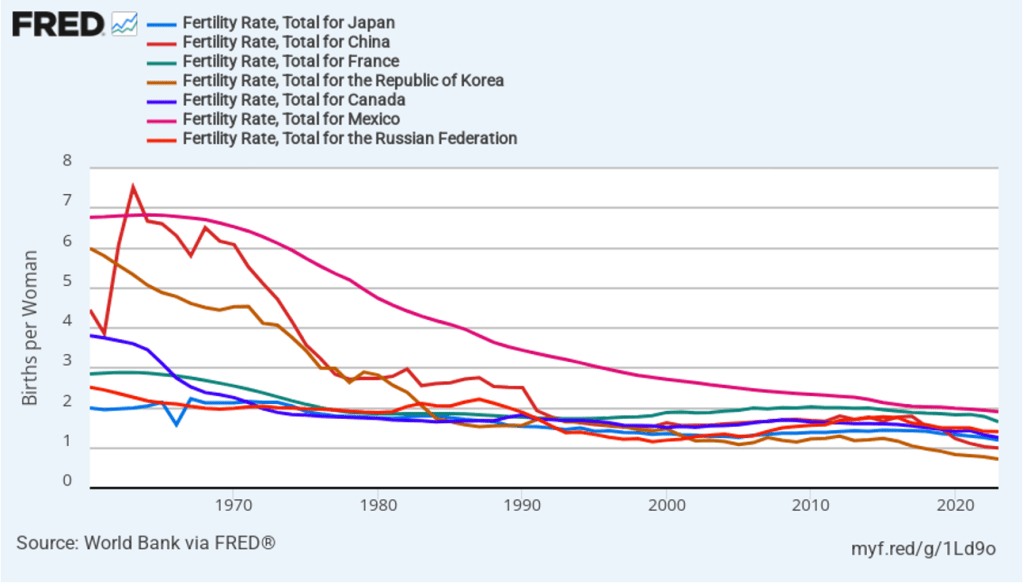

The United States is not alone in experiencing a sharp decline in its TFR since the 1960s. The following figure shows some other countries that currently have below replacement level fertility, including some countries—such as China, Japan, Korea, and Mexico—in which TFRs were well above 5 in the 1960s. In fact, only a relatively few countries, such as Israel and some countries in sub-Saharan Africa are still experiencing above replacement level fertility.

An aging population raises the number of retired people relative to the number of workers, making it difficult for governments to finance pensions and health care for older people. We discuss this problem with respect to the U.S. Social Security and Medicare programs in an Apply the Concept in Macroeconomics, Chapter 16 (Economics, Chapter 26 and Essentials of Economics, Chapter 18). Countries experiencing a declining population typically also experience lower rates of economic growth than do countries with growing populations. Finally, as we discuss in an Apply the Concept in Microeconomics, Chapter 3, different generations often differ in the mix of products they buy. For instance, a declining number of children results in declining demand for diapers, strollers, and toys.