Image of “a woman shopping in a grocery store” generated by ChatGTP 4o.

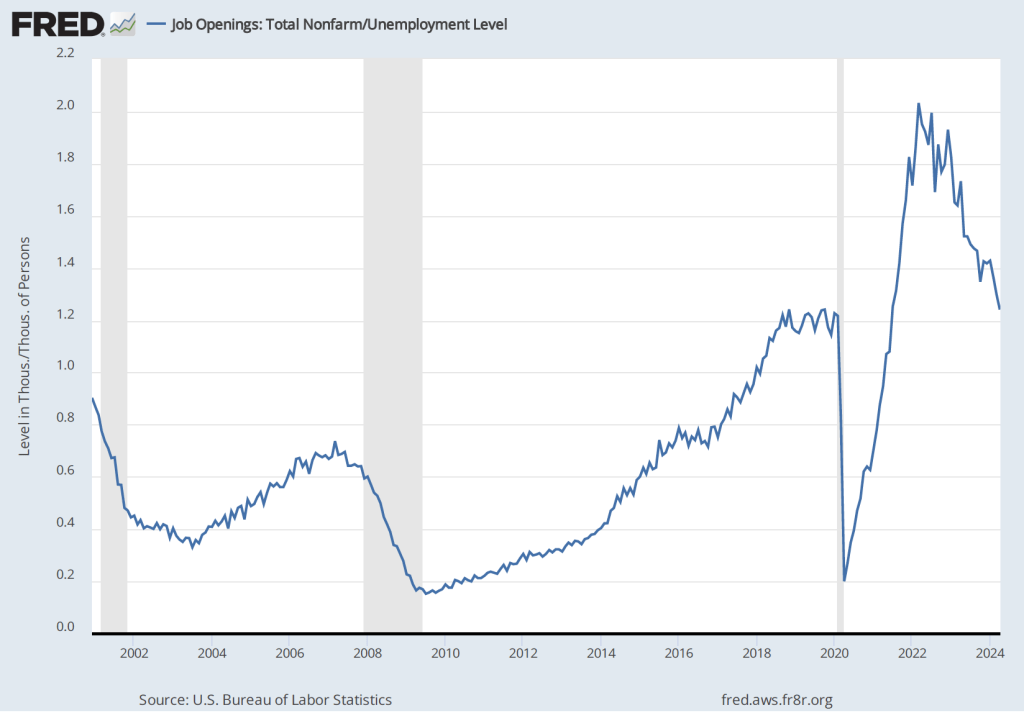

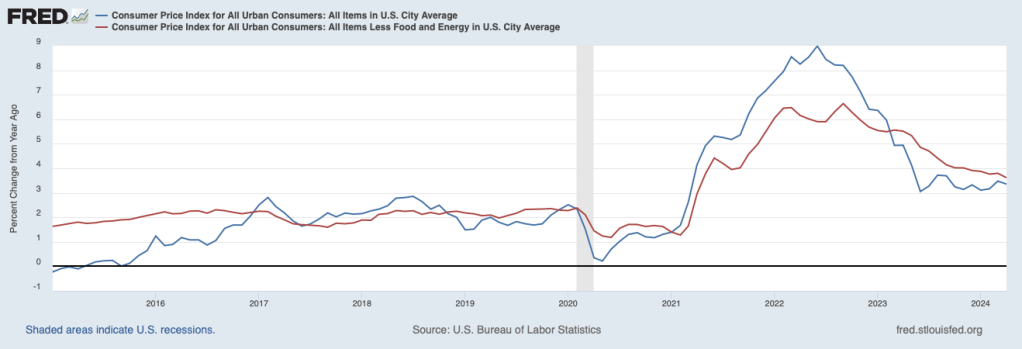

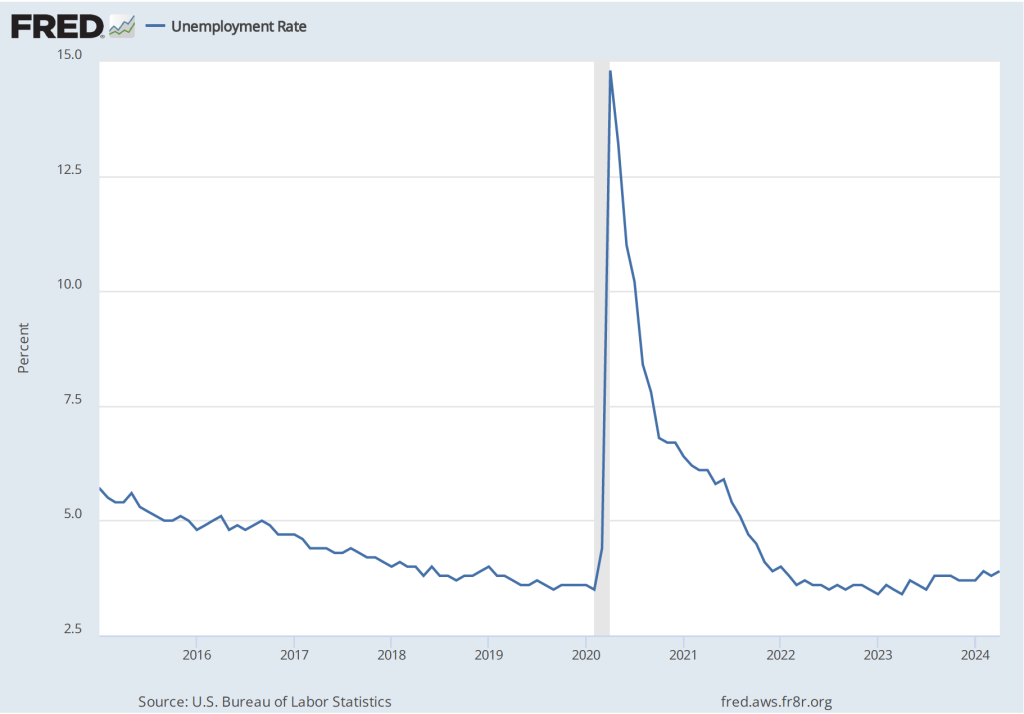

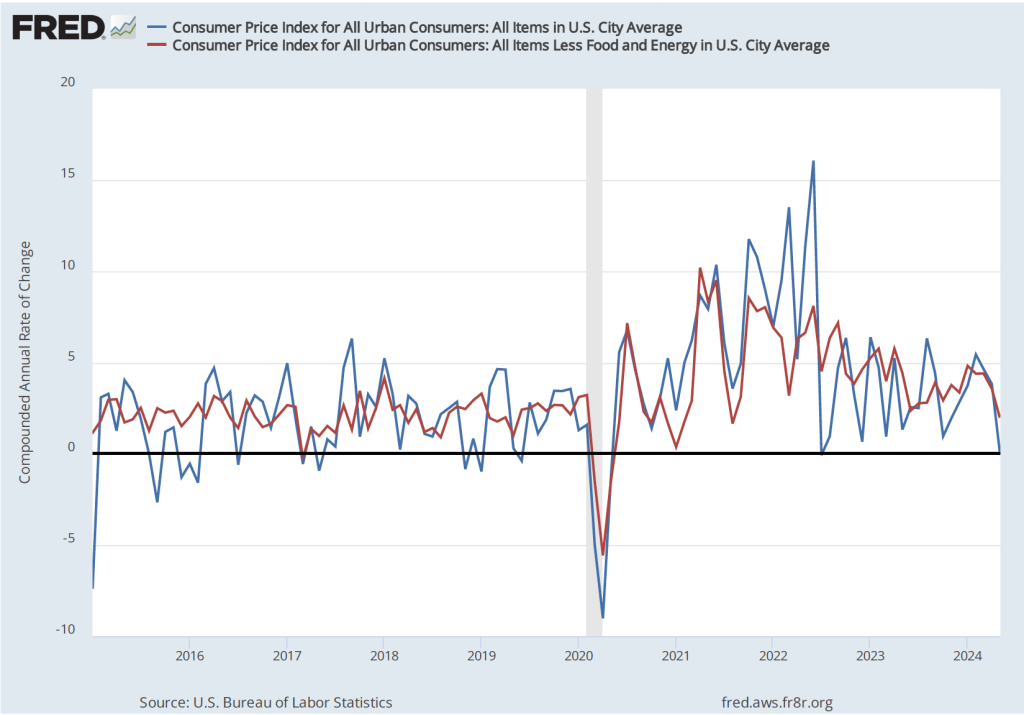

Today (June 12) we had the unusual coincidence of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) releasing its monthly report on the consumer price index (CPI) on the same day that the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) concluded a meeting. The CPI report showed that the inflation rate had slowed more than expected. As the following figure shows, the inflation rate for May measured by the percentage change in the CPI from the same month in the previous month—headline inflation (the blue line)—was 3.3 percent—slightly below the 3.4 percent rate that economists surveyed by the Wall Street Journal had expected, and slightly lower than the 3.4 percent rate in April. Core inflation (the red line(—which excludes the prices of food and energy—was 3.4 percent in May, down from 3.6 percent in April and slightly lower than the 3.5 percent rate that economists had been expecting.

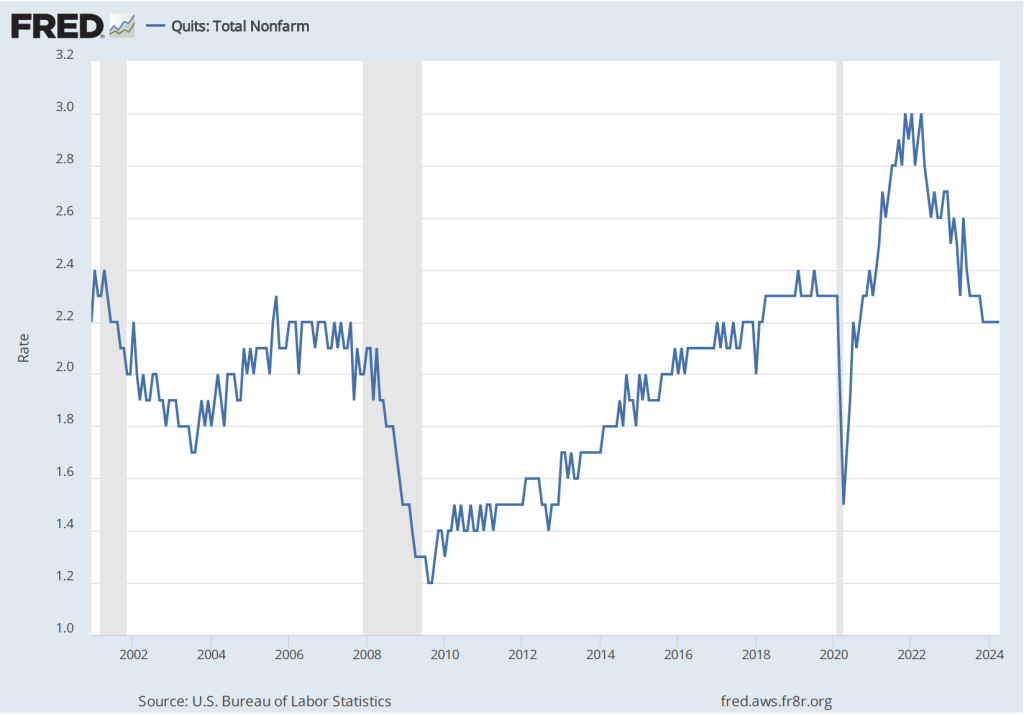

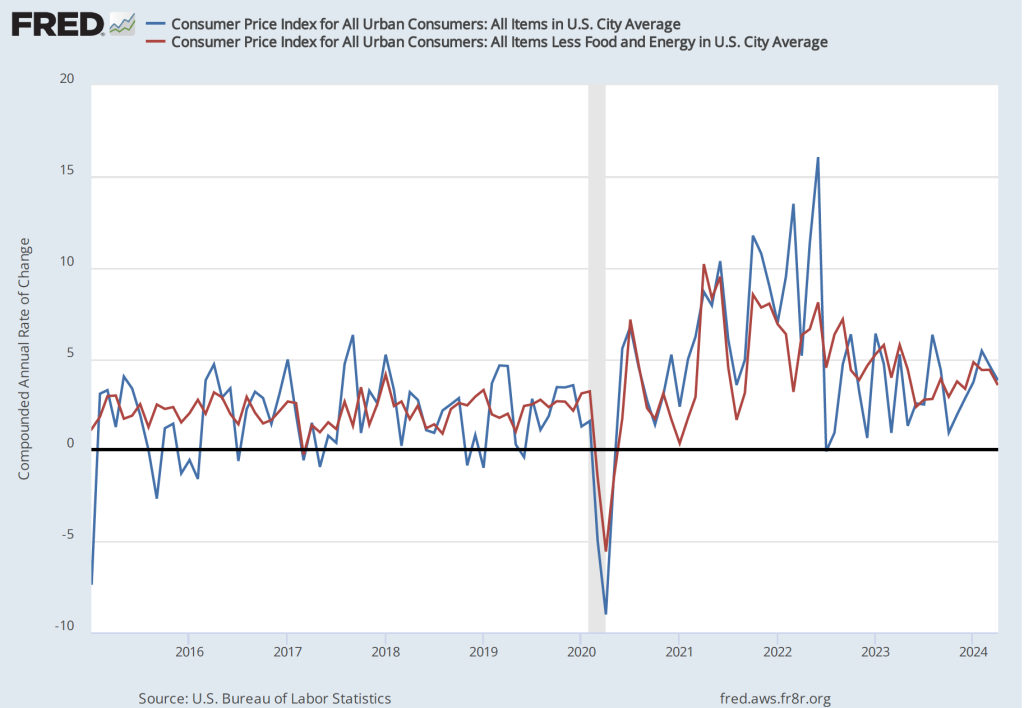

As the following figure shows, if we look at the 1-month inflation rate for headline and core inflation—that is the annual inflation rate calculated by compounding the current month’s rate over an entire year—the declines in the inflation rate are much larger. Headline inflation (the blue line) declined from 3.8 percent in April to 0.1 percent in May. Core inflation (the red line) declined from 3.6 percent in April to 2.0 percent in May. Overall, we can say that inflation has cooled in May and if inflation were to continue at the 1-month rate, the Fed will have succeeded in bringing the U.S. economy in for a soft landing—with the annual inflation rate returning to the Fed’s 2 percent target without the economy being pushed into a recession.

But two important notes of caution:

1. It’s hazardous to rely to heavily on data from a single month. Over the past year, the BLS has reported monthly inflation rates that were higher than economists expected and rates that was lower than economists expected. The current low inflation rate would have to persist over at least a few more months before we can safely conclude that the Fed has achieved a safe landing.

2. As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 15, Section 15.5 (Economics, Chapter 25, Section 25.5), the Fed uses the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index, rather than the CPI in evaluating whether it is hitting its 2 percent inflation target. So, today’s encouraging CPI data would have to carry over to the PCE data that the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) will release on January 28 before we can conclude that inflation as the Fed tracks it did in fact slow significantly in April.

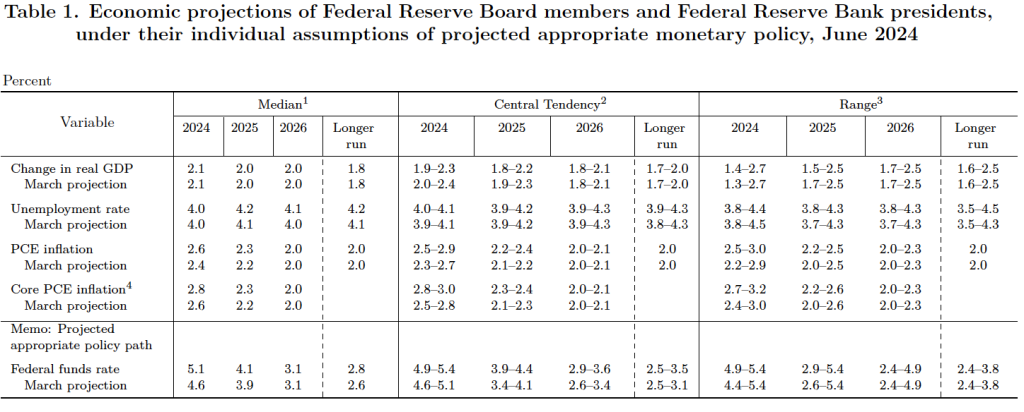

The BLS released the CPI report at 8:30 am eastern time. The FOMC began its meeting later in the day and so committee members were able to include in their deliberations today’s CPI data along with other previously available information on the state of the economy. At the close of the meeting, , the FOMC released a statement in which it stated, as expected, that it would leave its target range for the federal funds rate unchanged at 5.25 percent to 5.50 percent. After the meeting, the committee also released—as it typically does at its March, June, September, and December meetings—a “Summary of Economic Projections” (SEP), which presents median values of the committee members’ forecasts of key economic variables. The values are summarized in the following table, reproduced from the release.

The table shows that compared with their projections in March—the last time the FOMC published the SEP—committee members were expecting higher headline and core PCE inflation and a higher federal funds rate at the end of this year. In the long run, committee members were expecting a somewhat highr unemployment rate and somewhat higher federal funds rate than they had expected in March.

Note, as we discuss in Macreconomics, Chapter 14, Section 14.4 (Economics, Chapter 24, Section 24.4 and Essentials of Economics, Chapter 16, Section 16.4), there are twelve voting members of the FOMC: the seven members of the Board of Governors, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and presidents of four of the other 11 Federal Reserve Banks, who serve one-year rotating terms. In 2024, the presidents of the Richmond, Atlanta, San Francisco, and Cleveland Feds are voting members. The other Federal Reserve Bank presidents serve as non-voting members, who participate in committee discussions and whose economic projections are included in the SEP.

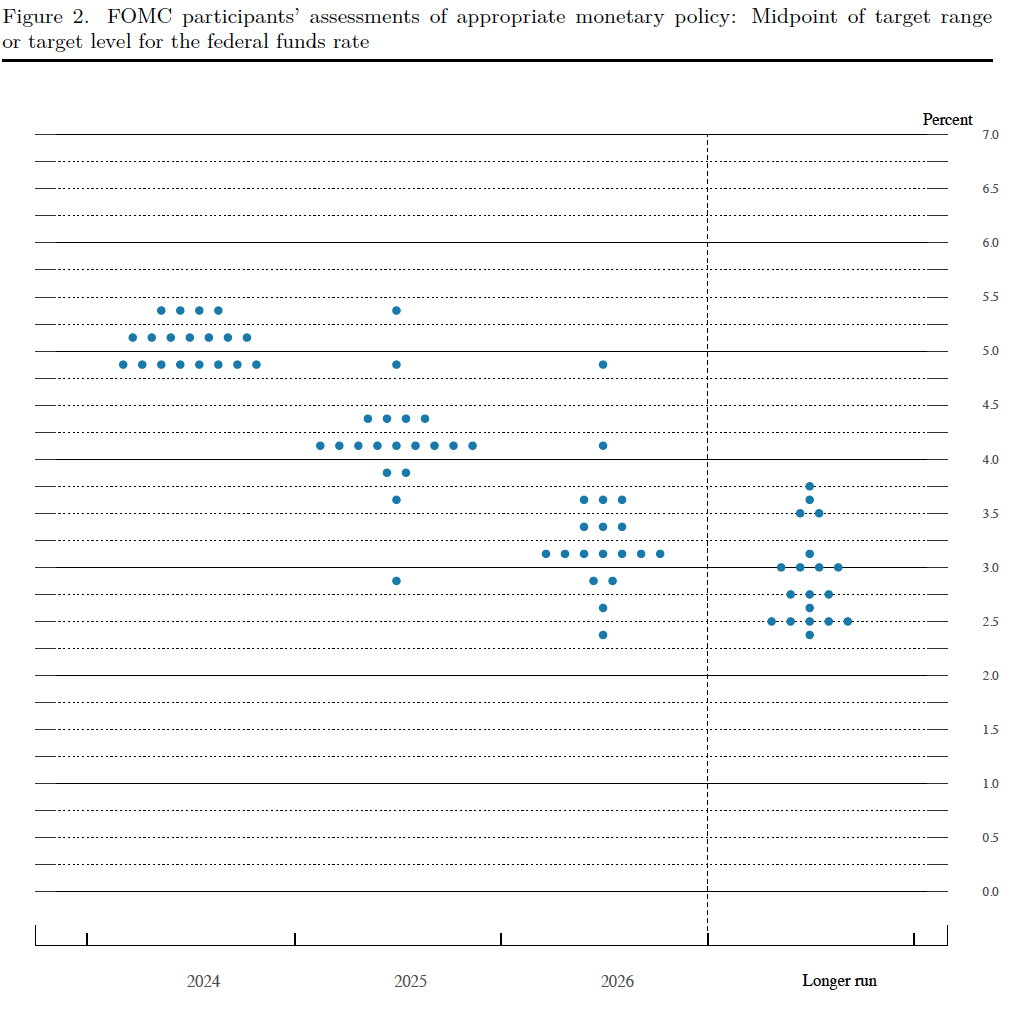

Prior to the meeting there was much discussion in the business press and among investment analysts about the dot plot, shown below. Each dot in the plot represents the projection of an individual committee member. (The committee doesn’t disclose which member is associated with which dot.) Note that there are 19 dots, representing the 7 members of the Fed’s Board of Governors and all 12 presidents of the Fed’s district banks.

The plots on the far left of the figure represent the projections of each of the 19 members of the value of the federal funds rate at the end of 2024. Four members expect that the target for the federal funds rate will be unchanged at the end of the year. Seven members expect that the committee will cut the target range once, by 0.25 percentage point, by the end of the year. And eight members expect that the cut target range twice, by a total of 0.50 percent point, by the end of the year. Members of the business media and financial analysts were expecting tht the dot plot would project either one or two target rate cuts by the end of the year. The committee was closely divided among those two projections, with the median projection being for a single rate cut.

In its statement following the meeting, the committee noted that:

“In considering any adjustments to the target range for the federal funds rate, the Committee will carefully assess incoming data, the evolving outlook, and the balance of risks. The Committee does not expect it will be appropriate to reduce the target range until it has gained greater confidence that inflation is moving sustainably toward 2 percent. In addition, the Committee will continue reducing its holdings of Treasury securities and agency debt and agency mortgage‐backed securities. The Committee is strongly committed to returning inflation to its 2 percent objective.”

In his press conference after the meeting, Fed Chair Jerome Powell noted that the morning’s CPI report was a “Better inflation report than nearly anyone expected.” But, Powell also noted that: “You don’t want to be motivated any one data point.” Reinforcing the view quoted above in the committee’s statement, Powell emphasized that before cutting the target for the federal funds rate, the committee would need “Greater confidence that inflation is moving back to 2% on a sustainable basis.”

In summary, today’s CPI report was an indication that the Fed is on track to bring about a soft landing, but the FOMC will be closely analyzing macroeconomic data over at least the next few months before it is willing to cut its target for the federal funds rate.