In this photo of a Federal Open Market Committee meeting, Fed Chair Jerome Powell is on the far left and Fed Governor Christopher Waller is the third person to Powell’s left. (Photo from federalreserve.gov)

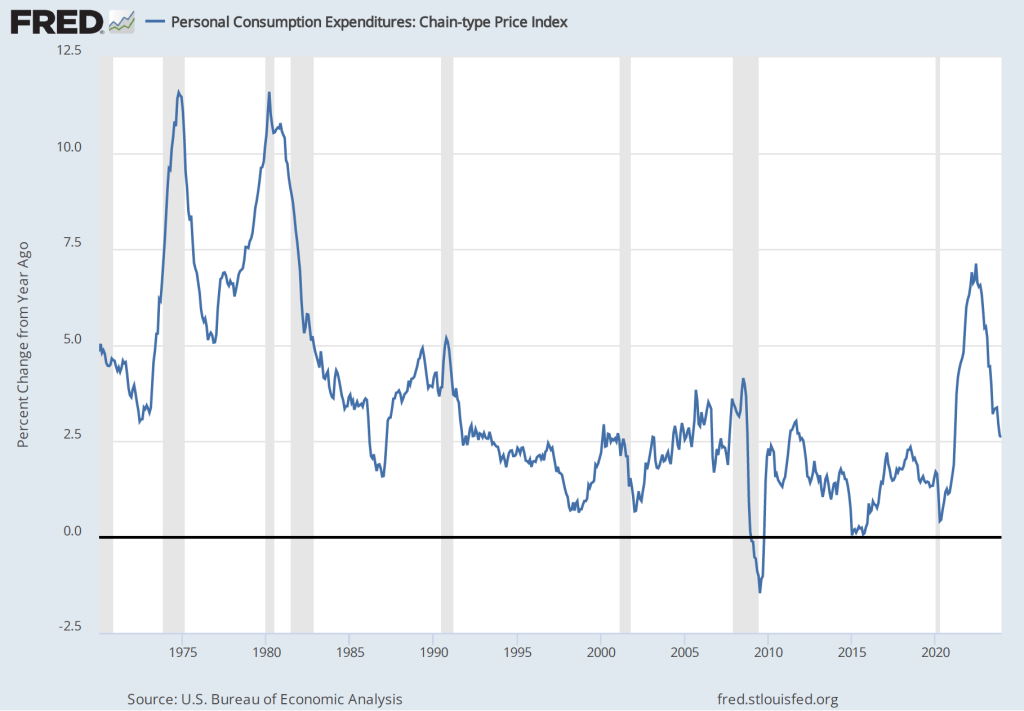

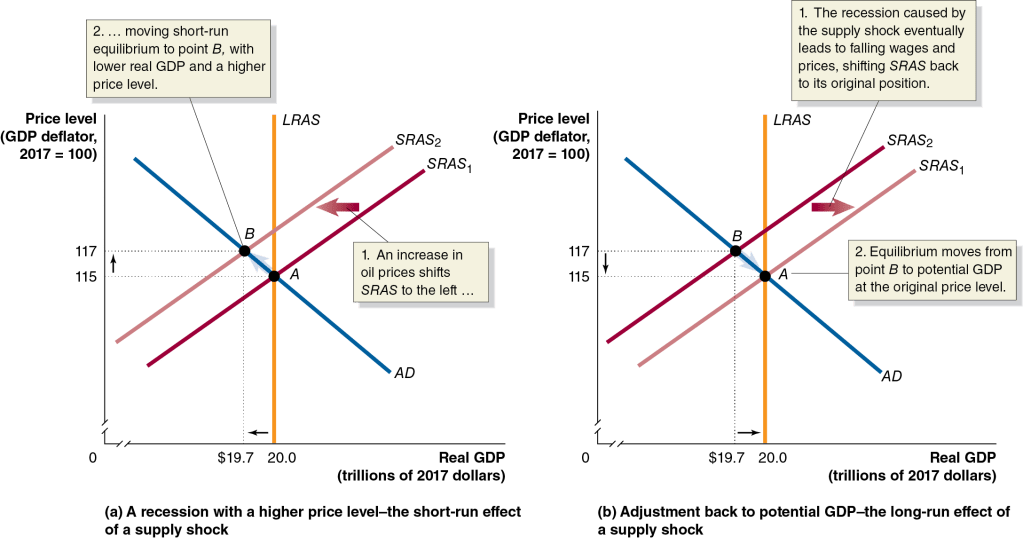

This post discusses two developments this week that involve the Federal Reserve. First, we discuss the apparent disagreement between Fed Chair Jerome Powell and Fed Governor Christopher Waller over the best way to respond to the Trump Administration’s tariff increases. As we discuss in this blog post and in this podcast, in terms of the aggregate demand and aggregate supply model, a large unexpected increase in tariffs results in an aggregate supply shock to the economy, shifting the short-run aggregate supply curve (SRAS) to the left. The following is Figure 13.7 from Macroeconomics (Figure 23.7 from Economics) and illustrates the effects of an aggregate supply shock on short-run macroeconomic equilibrium.

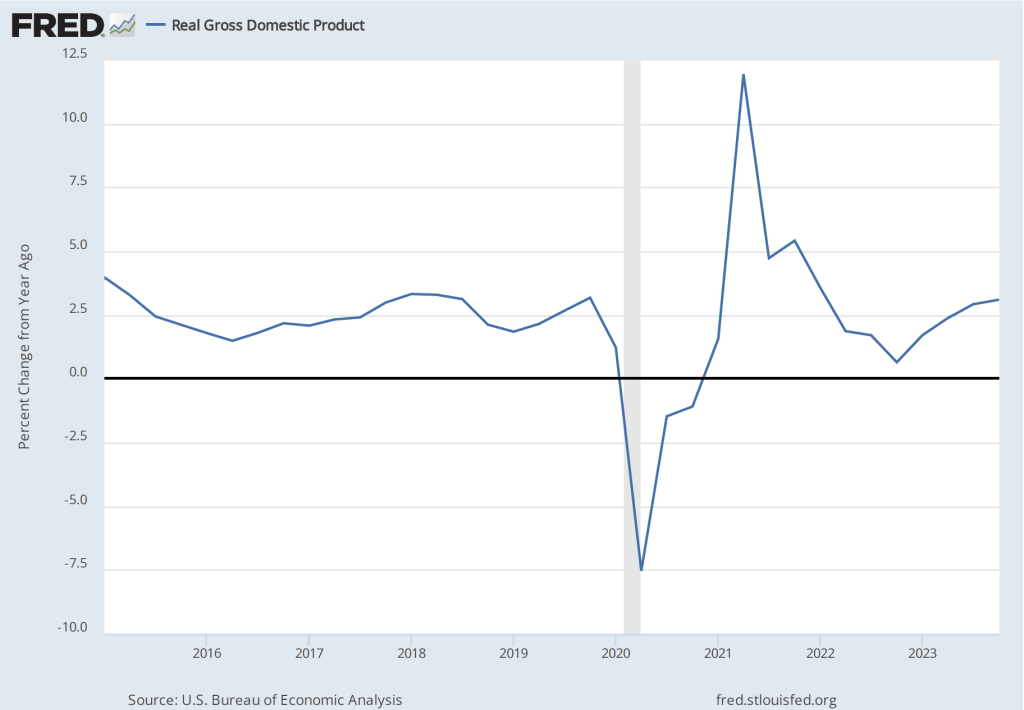

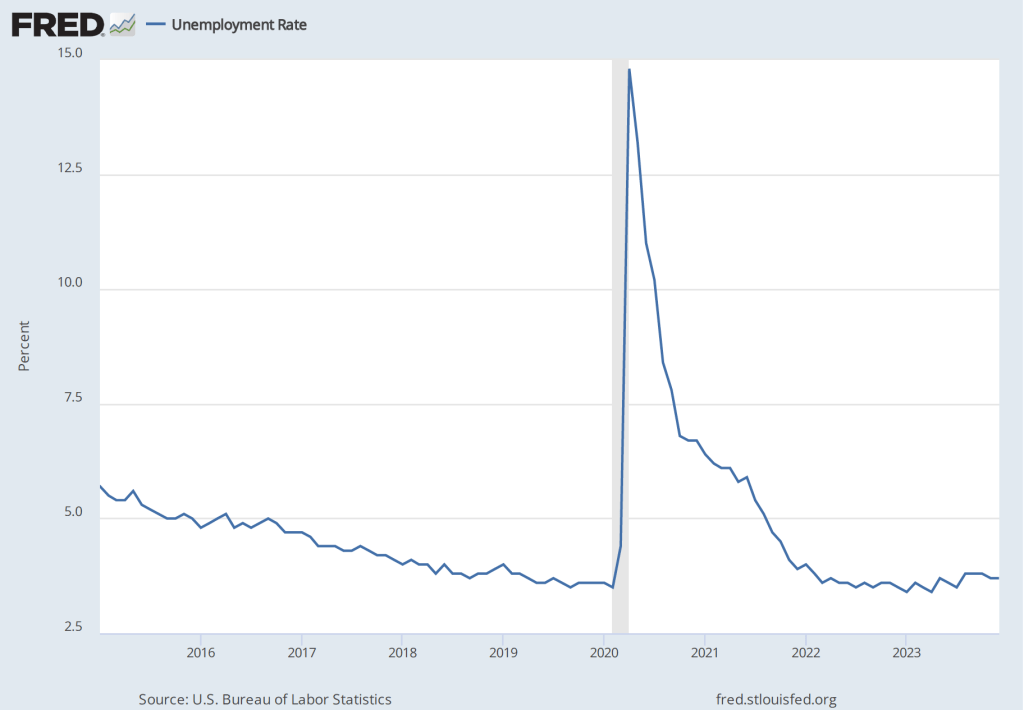

Although the figure shows the effects of an aggregate supply shock that results from an unexpected increase in oil prices, using this model, the result is the same for an aggregate supply shock caused by an unexpected increase in tariffs. Two-thirds of U.S. imports are raw materials, intermediate goods, or capital goods, all of which are used as inputs by U.S. firms. So, in both the case of an increase in oil prices and in the case of an increase in tariffs, the result of the supply shock is an increase in U.S. firms’ production costs. This increase in costs reduces the quantity of goods firms will supply at every price level, shifting the SRAS curve to the left, as shown in panel (a) of the figure. In the new macroeconomic equilibrium, point B in panel (a), the price level increases and the level of real GDP declines. The decline in real GDP will likely result in an increase in the unemployment rate.

An aggregate supply shock poses a policy dilemma for the Fed’s policymaking Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). If the FOMC responds to the decline n real GDP and the increase in the unemployment rate with an expansionary monetary policy of lowering the target for the federal funds rate, the result is likely to be a further increase in the price level. Using a contractionary monetary policy of increasing the target for the federla funds rate to deal with the rising price level can cause real GDP to fall further, possibly pushing the economy into a recession. One way to avoid the policy dilemma from an aggregate supply shock caused by an increase in tariffs is for the FOMC to “look through”—that is, not respond—to the increase in tariffs. As panel (b) in the figure shows, if the FOMC looks through the tariff increase, the effect of the aggregate supply shock can be transitory as the economy absorbs the one-time increase in the price level. In time, real GDP will return to equilibrium at potential real GDP and the unemployment rate will fall back to the natural rate of unemployment.

On Monday (April 14), Fed Governor Christopher Waller in a speech to the Certified Financial Analysts Society of St. Louis made the argument for either looking through the macroeconomic effects of the tariff increase—even if the tariff increase turns out to be large, which at this time is unclear—or responding to the negative effects of the tariffs increases on real GDP and unemployment:

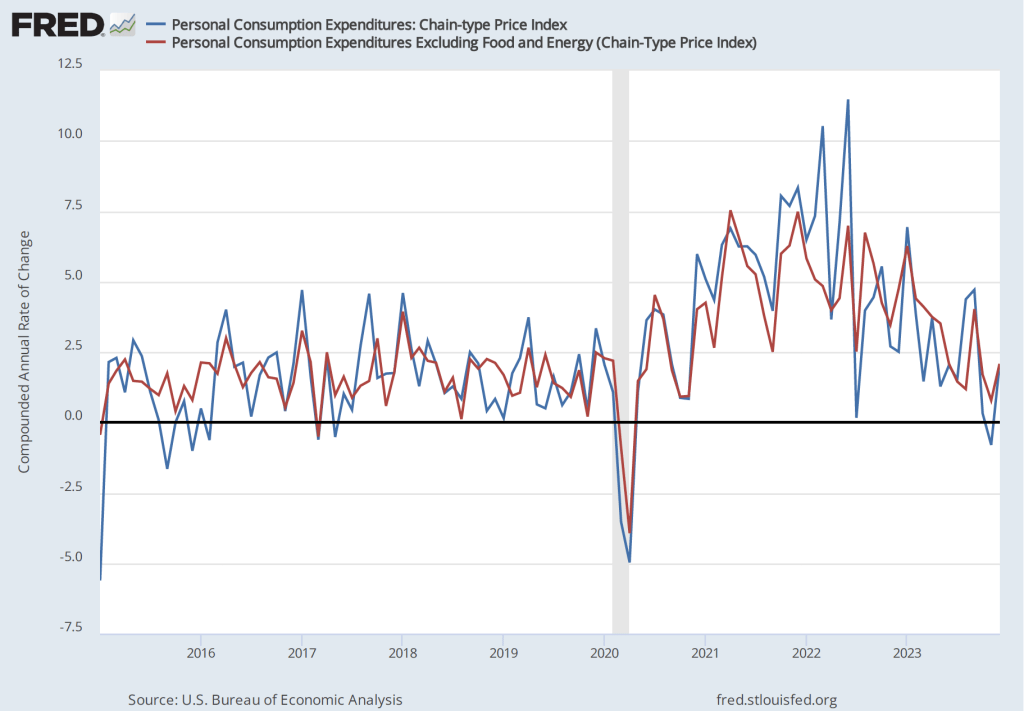

“I am saying that I expect that elevated inflation would be temporary, and ‘temporary’ is another word for ‘transitory.’ Despite the fact that the last surge of inflation beginning in 2021 lasted longer than I and other policymakers initially expected, my best judgment is that higher inflation from tariffs will be temporary…. While I expect the inflationary effects of higher tariffs to be temporary, their effects on output and employment could be longer-lasting and an important factor in determining the appropriate stance of monetary policy. If the slowdown is significant and even threatens a recession, then I would expect to favor cutting the FOMC’s policy rate sooner, and to a greater extent than I had previously thought.”

In a press conference after the last FOMC meeting on March 19, Fed Chair Jerome Powell took a similar position, arguing that: “If there’s an inflation that’s going to go away on its own, it’s not the correct response to tighten policy.” But in a speech yesterday (April 16) at the Economic Club of Chicago, Powell indicated that looking through the increase in the price level resulting from a tariff increase might be a mistake:

“The level of the tariff increases announced so far is significantly larger than anticipated. The same is likely to be true of the economic effects, which will include higher inflation and slower growth. Both survey- and market-based measures of near-term inflation expectations have moved up significantly, with survey participants pointing to tariffs…. Tariffs are highly likely to generate at least a temporary rise in inflation. The inflationary effects could also be more persistent…. Our obligation is to keep longer-term inflation expectations well anchored and to make certain that a one-time increase in the price level does not become an ongoing inflation problem.”

In a discussion following his speech, Powell argued that tariff increases may disrupt global supply chains for some U.S. industries, such as automobiles, in way that could be similar to the disruptions caused by the Covid pandemic of 2020. As a result: “When you think about supply disruptions, that is the kind of thing that can take time to resolve and it can lead what would’ve been a one-time inflation shock to be extended, perhaps more persistent.” Whereas Waller seemed to indicate that as a result of the tariff increases the FOMC might be led to cut its target for the federal funds sooner or to larger extent in order to meet the maximum employment part of its dual mandate, Powell seemed to indicate that the FOMC might keep its target unchanged longer in order to meet the price stability part of the dual mandate.

Powell’s speech caught the notice of President Donald Trump who has been pushing the FOMC to cut its target for the federal funds rate sooner. An article in the Wall Street Journal, quoted Trump as posting to social media that: “Powell’s termination cannot come fast enough!” Powell’s term as Fed chair is scheduled to end in May 2026. Does Trump have the legal authority to replace Powell earlier than that? As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 27 (Economics Chapter 17), according to the Federal Reserve Act, once a Fed chair is notimated to a four-year term by the president (President Trump first nominated Powell to be chair in 2017 and Powell took office in 2018) and confirmed by the Senate, the president cannot remove the Fed chair except “for cause.” Most legal scholars argue that a president cannot remove a Fed chair due to a disagreement over monetary policy.

Article I, Section II of the Constitution of the United States states that: “The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.” The ability of Congress to limit the president’s power to appoint and remove heads of commissions, agencies, and other bodies in the executive branch of government—such as the Federal Reserve—is not clearly specified in the Constitution. In 1935, a unanimous Supreme Court ruled in the case of Humphrey’s Executor v. United States that President Franklin Roosevelt couldn’t remove a member of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) because in creating the FTC, Congress specified that members could only be removed for cause. Legal scholars have presumed that the ruling in this case would also bar attempts by a president to remove members of the Fed’s Board of Governors because of a disagreement over monetary policy.

The Trump Administration recently fired a member of the National Labor Relations Board and a member of the Merit Systems Protection Board. The members sued and the Supreme Court is considering the case. The Trump Adminstration is asking the Court to overturn the Humphrey’s Executor decision as having been wrongly decided because the decision infringed on the executive power given to the president by the Constitution. If the Court agrees with the administration and overturns the precdent established by Humphrey’s Executor, would President Trump be free to fire Chair Powell before Powell’s term ends? (An overview of the issues involved in this Court case can be found in this article from the Associated Press.)

The answer isn’t clear because, as we’ve noted in Macroeconomics, Chapter 14, Section 14.4, Congress gave the Fed an unusual hybrid public-private structure and the ability to fund its own operations without needing appropriations from Congress. It’s possible that the Court would rule that in overturning Humphrey’s Executor—if the Court should decide to do that—it wasn’t authorizing the president to replace the Fed chair at will. In response to a question following his speech yesterday, Powell seemed to indicate that the Fed’s unique structure might shield it from the effects of the Court’s decision.

If the Court were to overturn its ruling in Humphrey’s Executor and indicate that the ruling did authorize the president to remove the Fed chair, the Fed’s ability to conduce monetary policy independently of the president would be seriously undermined. In Macroeconomics, Chapter 17, Section 17.4 we review the arguments for and against Fed independence. It’s unclear at this point when the Court might rule on the case.