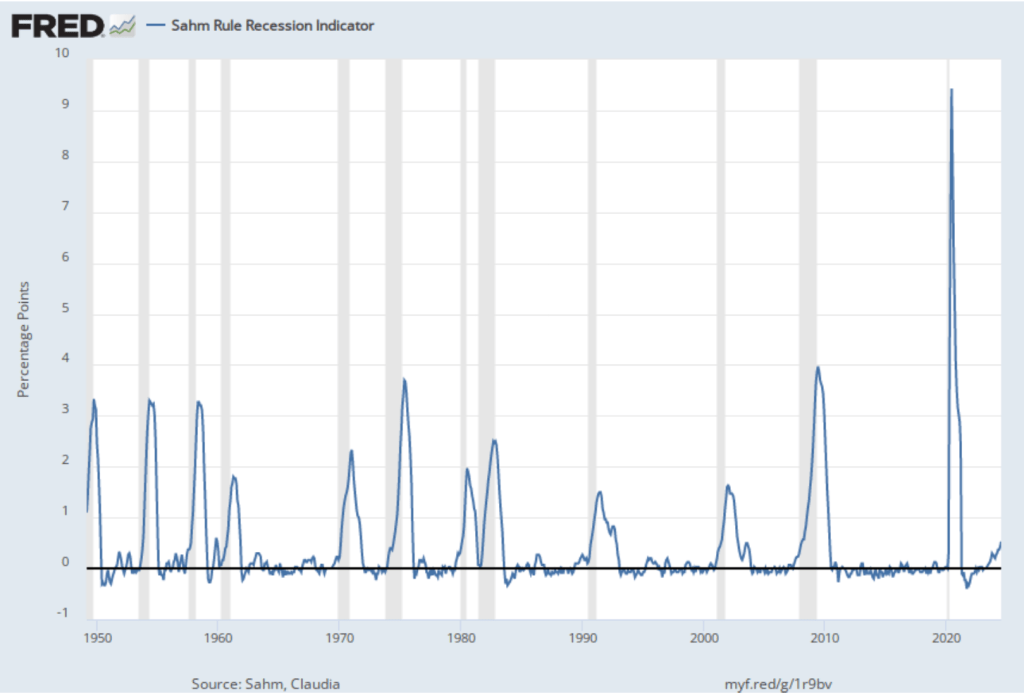

Over the first past few days, the stock and bond markets have gone through substantial swings as investors try to determine whether the U.S. economy is likely to move into a recession soon. (We discussed here the most recent BLS “Employment Situation” report, which was surprisingly weak.)

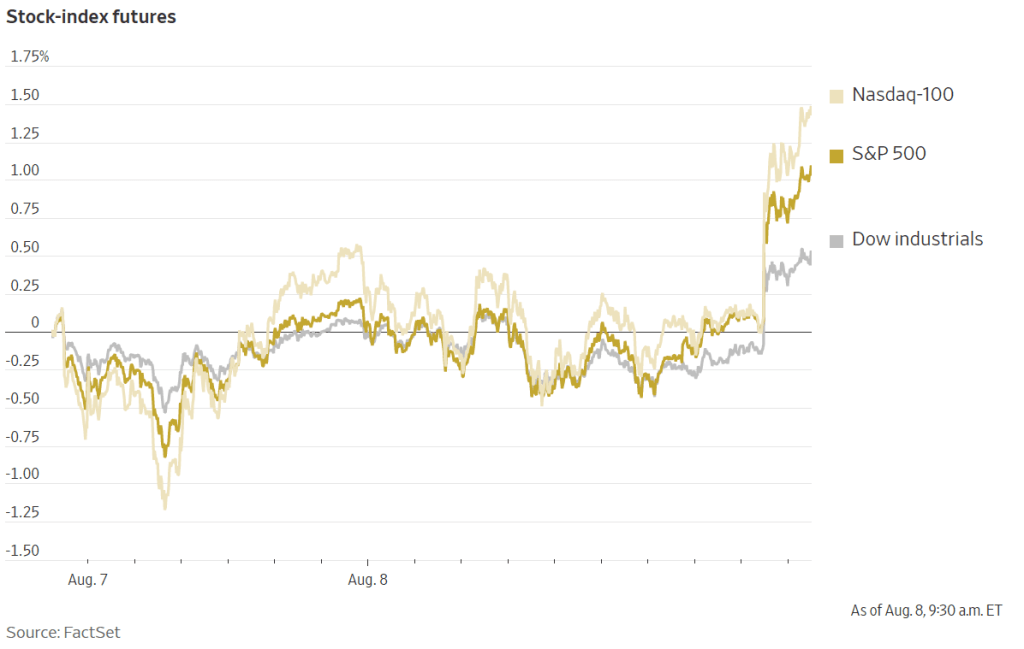

It’s difficult to determine with certainty why on a particular day stock and bond prices fluctuate. The following two figures from the Wall Street Journal show movements this morning (August 8) in stock prices and bond yields. (Recall that bond yields rise when bond prices fall, a point we discuss in the Appendix to Chapter 6 of Macroeconomics (Chapter 8 of Economics).)

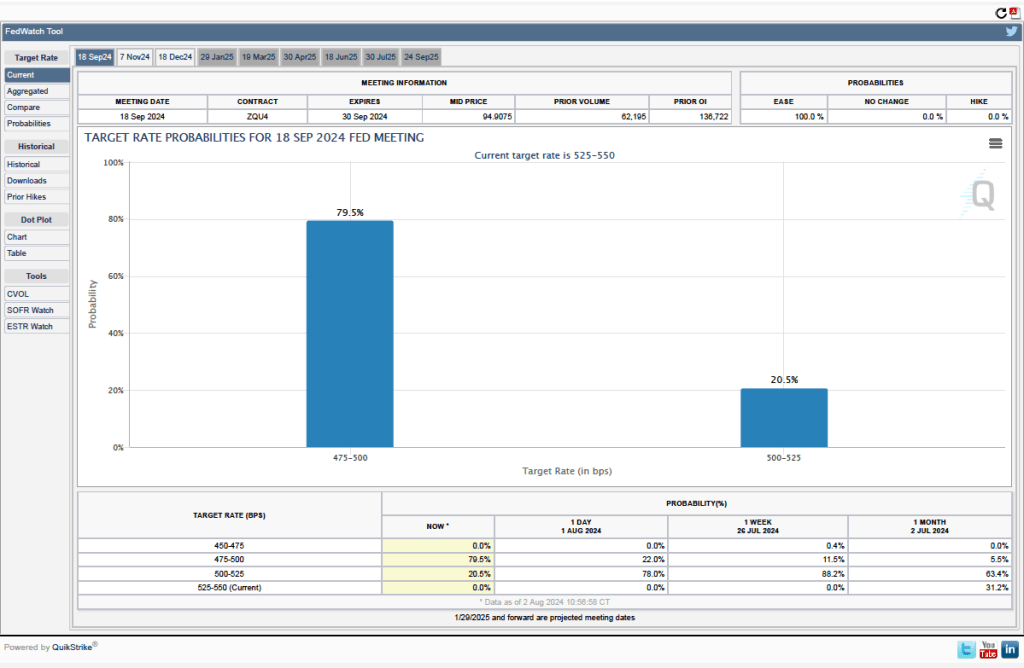

Rising stock prices and falling bond prices (rising bond yields) can be an indication that investors are more optimistic that the U.S. economy will avoid a recession. In a recession, profits decline, which is bad for stock prices. And in a recession, interest rates typically fall both because the Federal Reserve cuts it target range for the federal funds rate and because household and firms borrow less, which reduces the demand for loanable funds. Accordingly, most analysts are attributing the movements in stock and bond prices this morning to investors becoming more optimistic that the U.S. economy will avoid a recession.

Because of the level of uncertainty about the future path of the economy, investors are following very closely the release of new macroeconomic data. The Wall Street Journal and other business publications attributed the increase in investor optimism this morning to the U.S. Employment and Training Administration releasing at 8:30 a.m. its latest report on initial claims for unemployment insurance. The headline in the Wall Street Journal was: “Stocks Rise on Claims Data.” Similalry, the headline on bloomberg.com was: “Stocks Get Relief Rally after Jobless Claims Data.”

What are jobless claims? The first step when you lose a job and wish to receive government unemployment insurance payments is to file a claim, which starts the process by which an agency of the state government determines whether you are eligible to receive unemployment insurance payments.

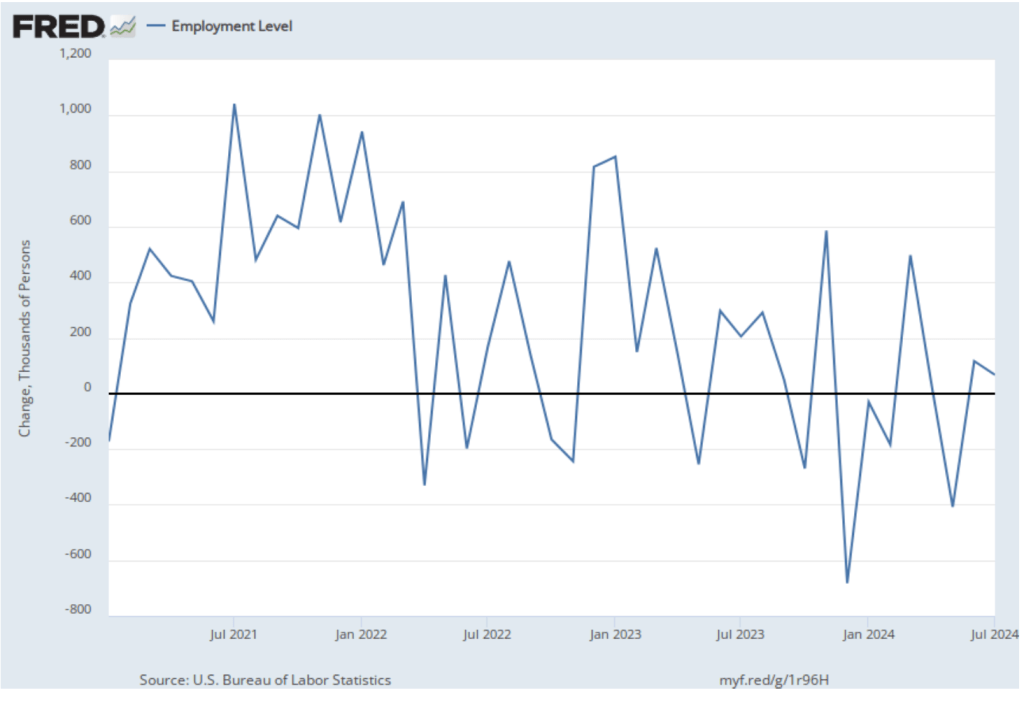

The data on initial jobless claims are released weekly. As the following figure shows, there is a lot of volatility in this data series. The latest data were favorable—which is thought to have caused the increase in stock prices and decline in bond prices—because new claims declined by 17,000 this week. But the series is so volatile that drawing conclusions from weekly changes seems unwarranted. For instance, the figure shows that weekly claims surged during the summer of 2023, although employment and production continued to expand during that period.

So it appears that people trading in stock and bond markets this morning are overreacting to this macrodata release. But explanations of why stock and bonds prices move as they do over a short period of time often turnout in hindsight to have been incorrect. It may well be the case that investors are acting as they are this morning for reasons that are, in fact, unrelated to the data on jobless claims.