An image of the U.S. Capitol generated by GTP-4o

Glenn serves on the the Grand Bargain Committee, chaired by Michael Strain of the American Enterprise Institute and Isabel Sawhill of the Brookings Institution. The committee, whose members span the political spectrum, have prepared a report that addresses some of the country’s most pressing economic and social problems.

Glenn and Michael Strain prepared the following introduction to the report. Below there is a link to the whole report.

The views expressed in this report are those of the individual authors who collectively constitute the Grand Bargain Committee, co-chaired by Michael R. Strain and Isabel V. Sawhill. This report was sponsored by the Center for Collaborative Democracy and was prepared independent of influence from the center and from any other outside party or institution. It is being published by the Bipartisan Policy Center as an example of how people with diverse views and political leanings can find common ground. The recommendations are strictly those of the policy experts and do not necessarily reflect the views of any organization or those of the BPC. All data are current as of November 2023.

By: Eric Hanushek, G. William Hoagland, Douglas Holtz-Eakin, R. Glenn Hubbard, Maya MacGuineas, Richard V. Reeves, Robert D. Resichauer, Gerard Robinson, Isabel V. Sawhill, Diane Schanzenbach, Richard Schmalensee, Michael R. Strain, and C. Eugene Steuerle.

Introduction

The United States faces serious economic and social challenges, including:

- The underlying economic growth rate has slowed, as have opportunities for people to move up the economic ladder.

- Our education system fails too many children and leaves many more with fewer opportunities than they deserve.

- The nation is not rising to the challenge of addressing climate change.

- Both our health care system and the health of our population need improvement.

- Our income tax system is broken, generating tax revenue in an inefficient and unfair manner.

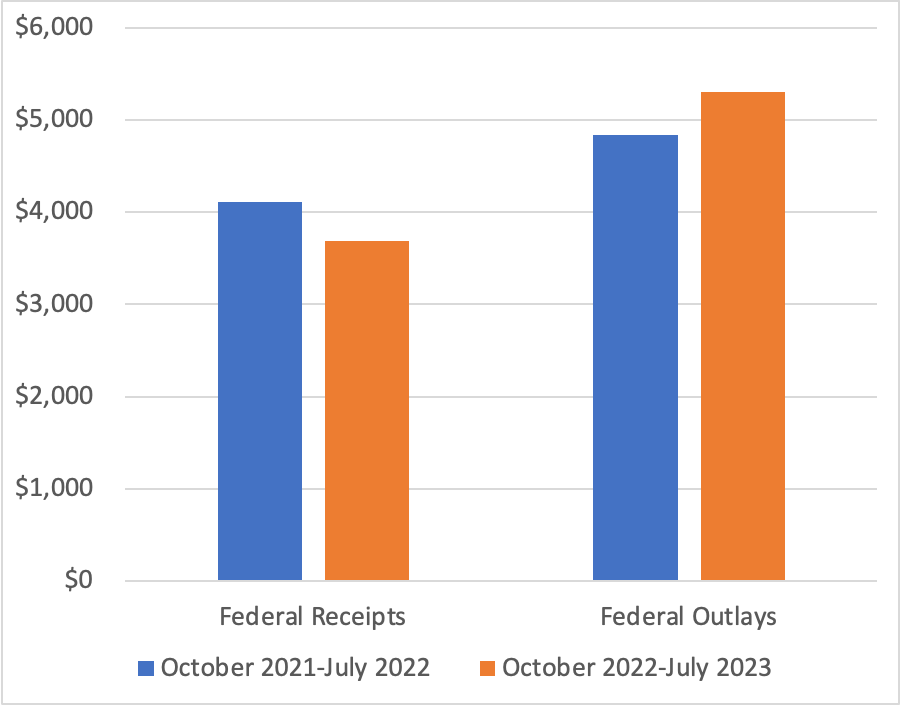

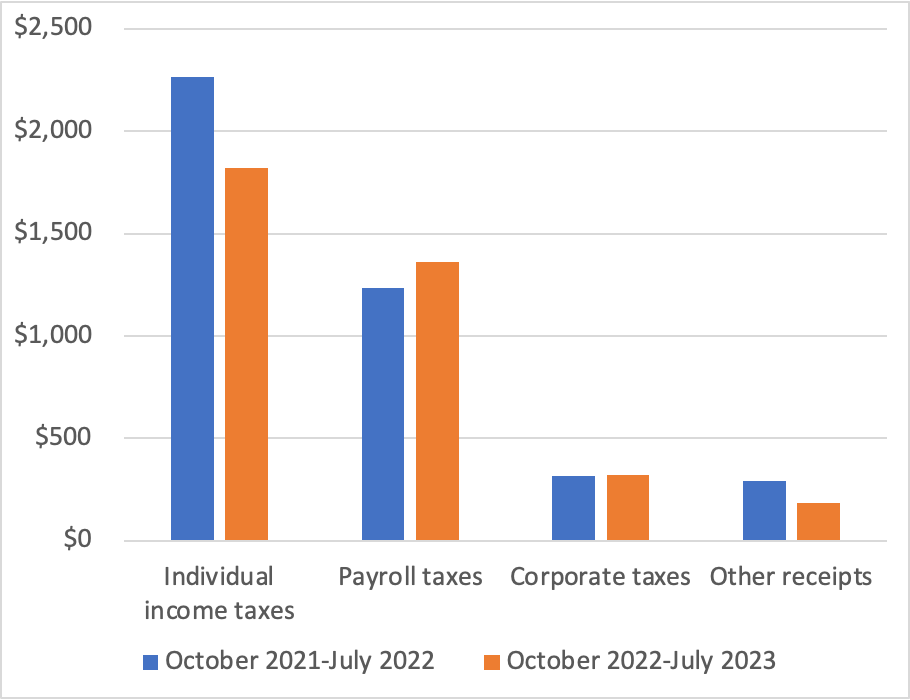

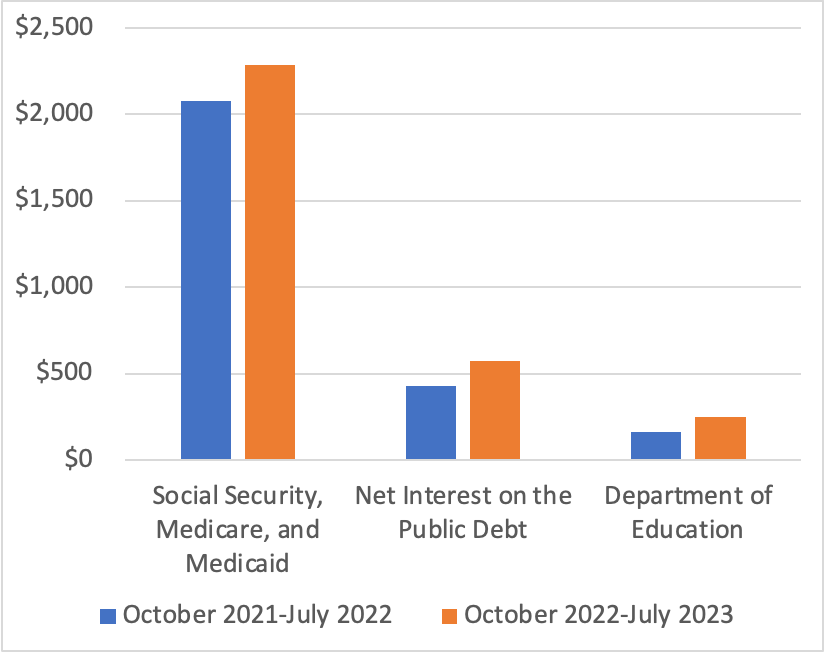

- And the national debt is growing at an unsustainable pace, threatening long-term economic growth, crowding out needed investments in economic opportunity, and placing the nation’s ability to respond to a future crisis at risk.

To address these problems, the Center for Collaborative Democracy commissioned subject matter experts—progressives, centrists, and conservatives—to develop a “Grand Bargain” encompassing all six issues. The policy debate typically puts these problems into silos, and within each silo, powerful forces support the status quo. This report seeks to break down these silos. Dealing with them all at once—in a Grand Bargain—is a more promising strategy than dealing with them individually, because it allows for different parties to strike deals across policy issues, not just within a single issue.

For example, implementing a carbon tax to address climate change seems impossibly difficult. So does increasing accountability for teacher performance. Trading one for the other might be easier than pursuing both in isolation. Fixing the structural budget deficit by reducing entitlement spending is an enormous political challenge. So is increasing spending on programs that advance economic opportunity. Doing both at the same time could be more politically feasible than addressing them separately.

In this context, the group of experts met for several months in 2023 to share perspectives and ideas and to come up with sensible policies in each of these areas: economic growth and mobility; education; environment; health; taxes; and the federal budget. The end result is this report, which is being published by the Bipartisan Policy Center as an example of how people with diverse views and political leanings can find common ground.

This report is short, consisting of less than 30 pages of text. Its brevity is by design. This constraint forced the group to stay focused on issues and recommendations that matter the most. The focus of the report is on concepts. It is designed to answer such questions as, “How should the nation’s approach to education or to the federal budget change? What fundamental reforms are required to increase the underlying rates of economic growth and upward mobility?” Focusing on concepts means not focusing on policy details, including the details of implementing our recommendations and of transitioning across policy regimes. Our lack of attention to policy details does not mean we do not recognize their importance. Of course, we do, and many members of the group have spent much of their careers studying and designing public policies. Instead, we focus on concepts because we believe the United States needs to return to a discussion of first principles. This report advances that objective.

Not every member of the group agrees with every recommendation in this report. That is not surprising given the diversity of views in the group, and the difficulty and complexity of many of the issues we address. Despite this disagreement, we were able to have an informed and constructive discussion about these economic issues, to find compromises, and to come up with a set of recommendations that we believe, on balance, would greatly strengthen the country and improve people’s lives.

We believe in the importance of a market economy. Free markets have led to unprecedented growth and innovation, along with rising incomes, over the past three centuries. But government also has a role to play. To unleash more growth, we need to curtail unneeded or overly costly regulations and to create a tax system that encourages investment spending and innovation. To bring prosperity to more people, we need policies that will enable more people to benefit from economic growth through investment in their education and skills. For this reason, we put a great deal of emphasis on improving education for children, on training or retraining for adult workers, and on subsidizing the earnings of low-wage workers when necessary while maintaining a safety net for those who cannot work.

Our proposals are designed to advance certain underlying values and themes: Work and savings should be rewarded, investment should be encouraged over consumption, public assistance should be better targeted to those most in need, the tax system should be more progressive, and the nation should invest relatively more in the young and spend relatively less on the elderly.

Our specific proposals in each area are as follows:

- On economic growth and mobility, we recommend investing in the education and training of workers, through community colleges and apprenticeships. We call for a more skill-based immigration system and for more immigrants; for encouraging innovation by investing more in basic research; for reducing taxes on new investment; for curbing unneeded regulation; for reducing the national debt; and for encouraging participation in economic life by increasing the generosity of earnings subsidies for low-wage workers.

- On education, we recommend improving the teacher workforce at the K-12 level; paying teachers more but strengthening the link between pay and performance; maintaining educational standards and accountability while narrowing gaps by race and class; expanding school choice; and recognizing the role that parents and families must play in students’ learning.

- On the environment, our main recommendation is to adopt a carbon tax. We also call for reducing methane emissions; expanding federal authority in the planning, siting, and permitting of the national electric transmission system; and repealing the renewable fuel standard that requires refiners to blend corn ethanol into the fuel they sell.

- On health, we call for giving more attention to the social determinants of poor health with a focus on the need for better nutrition, for rationalizing existing subsidies for health care, and for reducing health care costs.

- On taxes, we call for increasing tax revenue as a share of annual gross domestic product (GDP), and for that revenue to be raised in a manner that is more progressive, efficient, and simple than under current law, while also increasing the incentive to save and invest. For the business sector, that means allowing the expensing of investment expenditures and moving toward equal treatment of the corporate and noncorporate sectors.

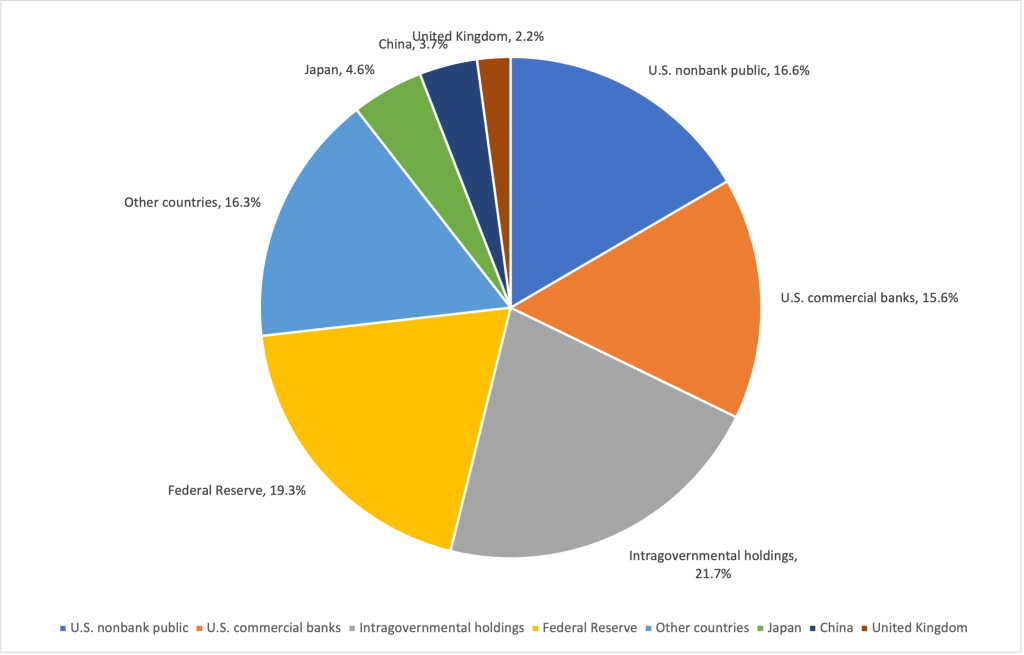

- On the federal budget, we recommend putting the debt as a share of annual GDP on a sustainable trajectory with a comprehensive package of reforms made up of a rough balance between tax increases and spending cuts in the initial years, phasing into a much larger share of the savings coming from spending cuts over time.

Most of these recommendations are at the federal level, but some are at the state and local level, particularly our education recommendations.

In the spirit of a Grand Bargain, these recommendations advance common goals and values through compromises both within and across policy areas. For example, one of our values is reflected in the goal of refocusing government spending on those who truly need it, and another is to restore fiscal responsibility. To accomplish this, we call for slower growth in Social Security and Medicare benefits for affluent seniors to reduce the major driver of the national debt, but we also protect vulnerable seniors and spend more on the education of children and on earnings subsidies for the working poor. We recommend adopting a carbon tax because it will simultaneously advance our goals of supporting the environment, increasing tax revenue, and boosting dynamism by encouraging innovation in the energy sector.

We believe the analysis and recommendations in this report point a path forward for the nation, but we offer them in a spirit of humility, understanding that others will disagree. We hope that this report catalyzes a much needed debate about the future of our nation.

View the full website here.

Read the full report here.