Image generated by ChatGPT

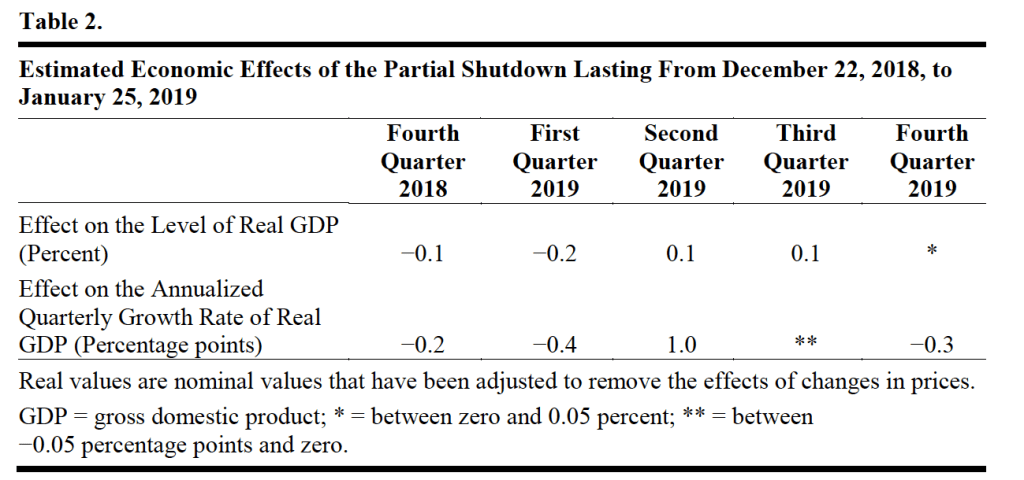

This morning (January 9), the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released its “Employment Situation” report (often called the “jobs report”) for December. Both the increase in employment and the unemployment rate were lower than had been expected.

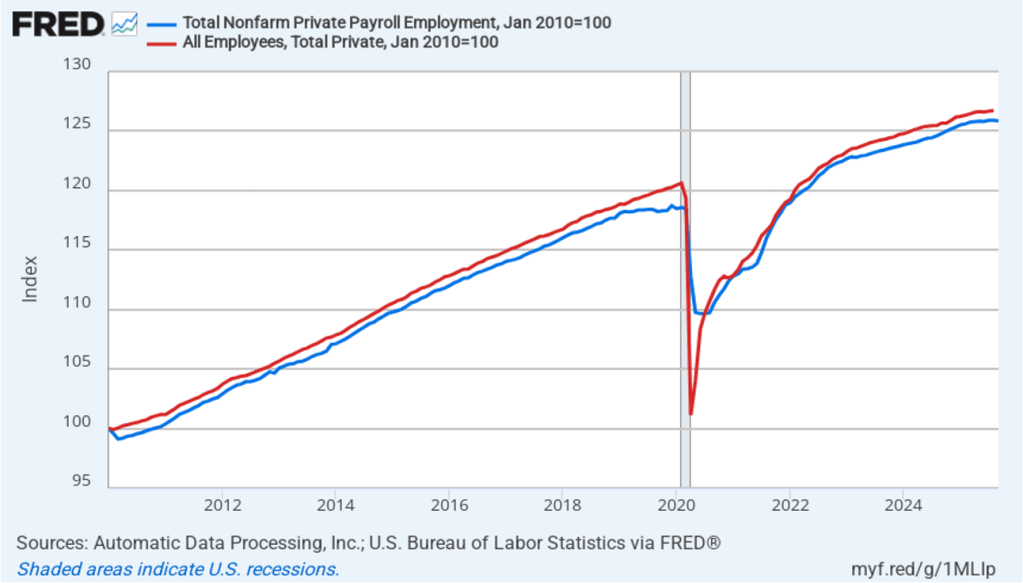

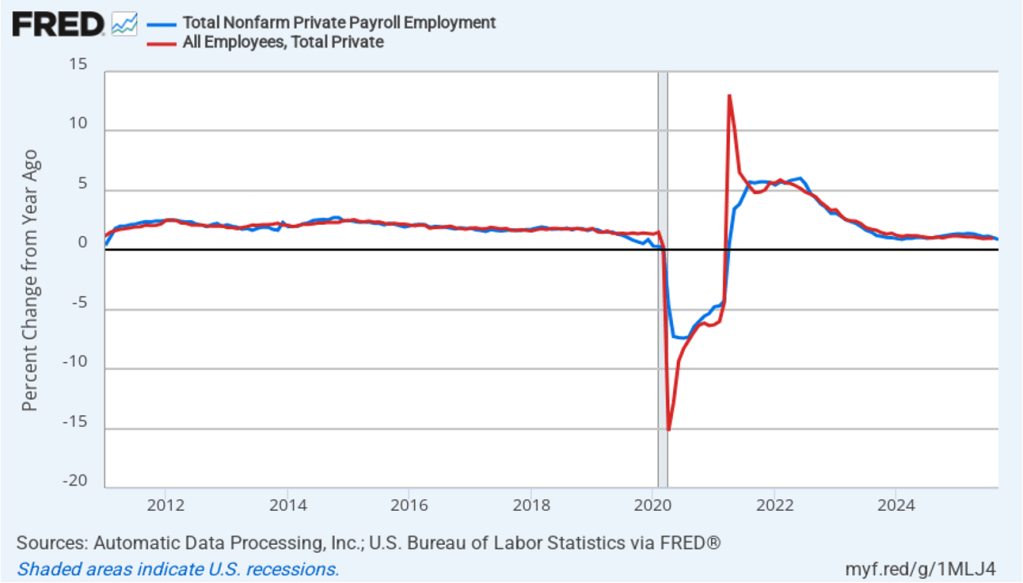

The jobs report has two estimates of the change in employment during the month: one estimate from the establishment survey, often referred to as the payroll survey, and one from the household survey. As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 9, Section 9.1 (Economics, Chapter 19, Section 19.1), many economists and Federal Reserve policymakers believe that employment data from the establishment survey provide a more accurate indicator of the state of the labor market than do the household survey’s employment data and unemployment data. (The groups included in the employment estimates from the two surveys are somewhat different, as we discuss in this post.)

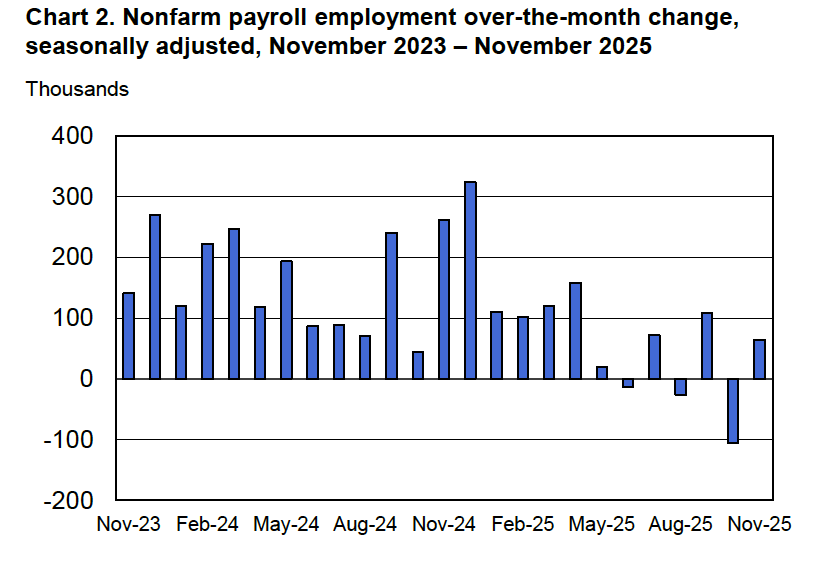

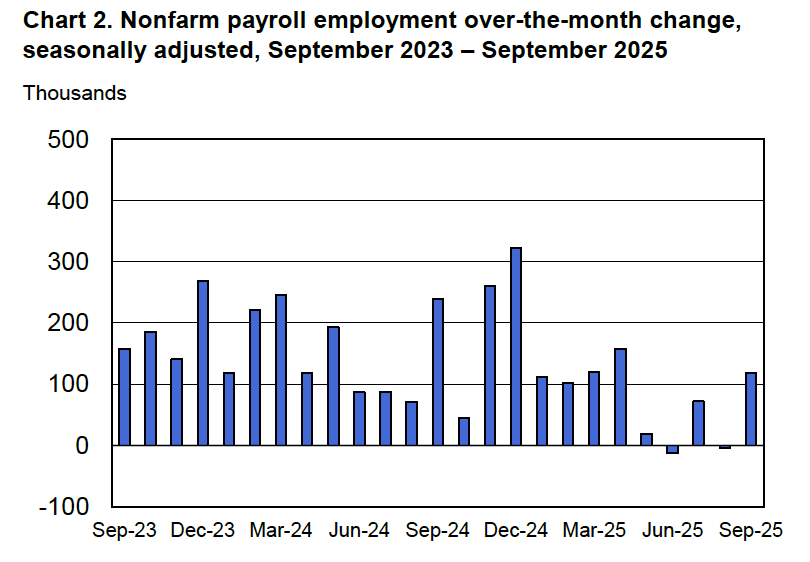

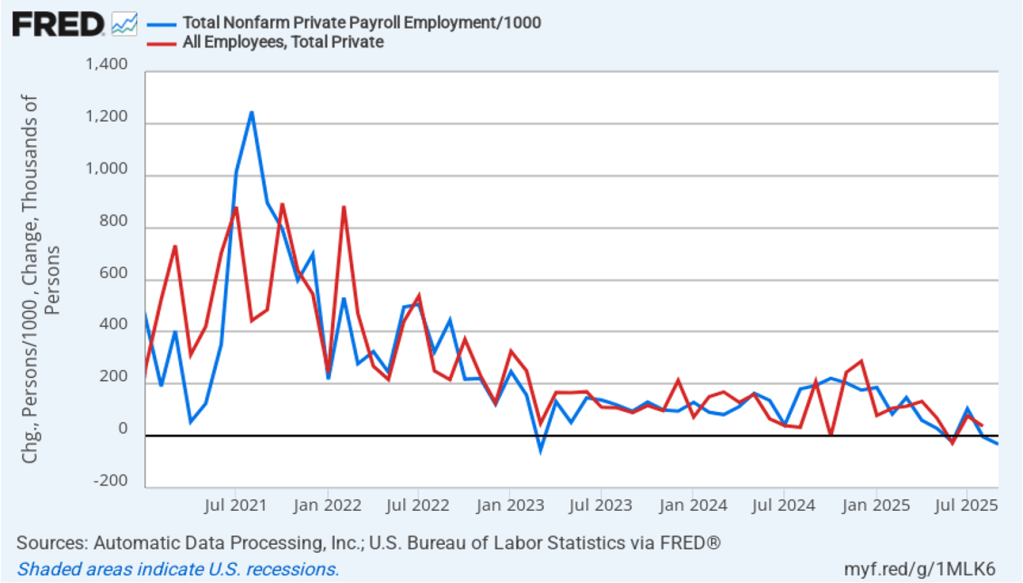

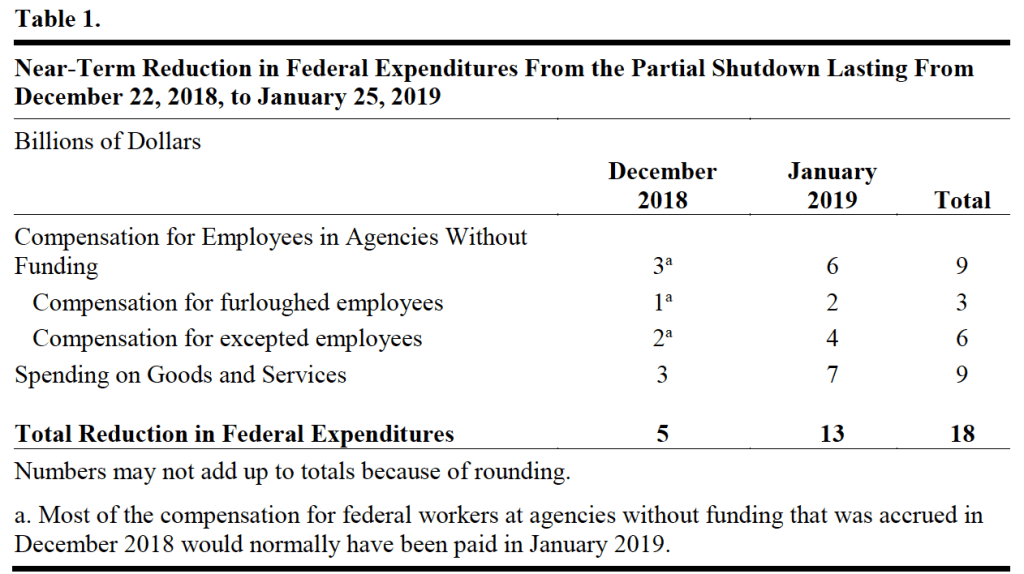

According to the establishment survey, there was a net increase of 50,000 nonfarm jobs during December. This increase was below the increase of 75,000 net new jobs that economists surveyed by FactSet had forecast. Economists surveyed by the Wall Street Journal had forecast an increase of 71,000 jobs. In addition, the BLS revised downward its previous estimates of employment in October and November by a combined 76,000 jobs. (The BLS notes that: “Monthly revisions result from additional reports received from businesses and government agencies since the last published estimates and from the recalculation of seasonal factors.”)

During 2025, the U.S. economy experienced an average monthly net increase of 49,000 jobs, down from an average monthly net increase of 168,000 jobs during 2024.

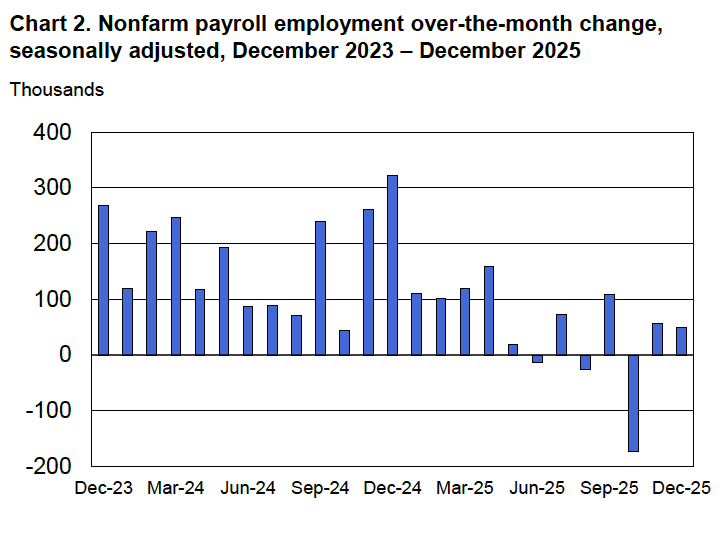

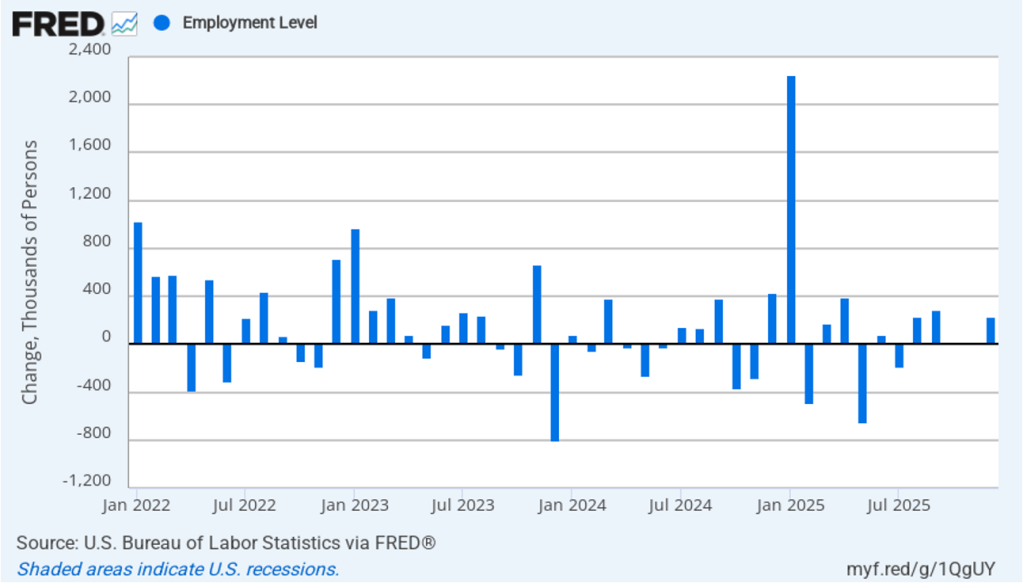

The following figure from the jobs report shows the net change in nonfarm payroll employment for each month in the last two years. The figure illustrates that monthly job growth has moved erratically since April. The Trump administration announced sharp increases in U.S. tariffs on April 2. Media reports indicate that some firms have slowed hiring due to the effects of the tariffs or in anticipation of those effects.

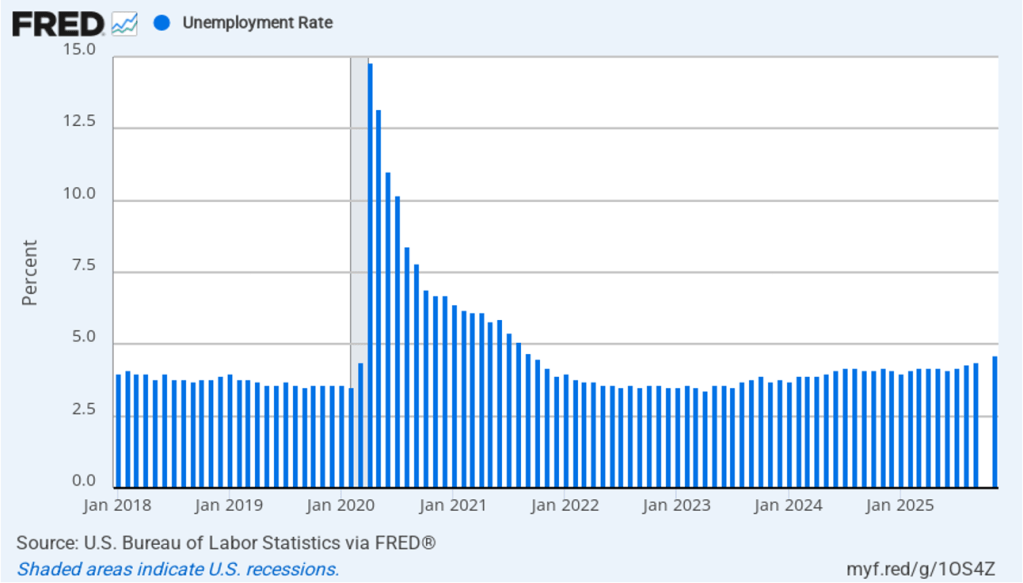

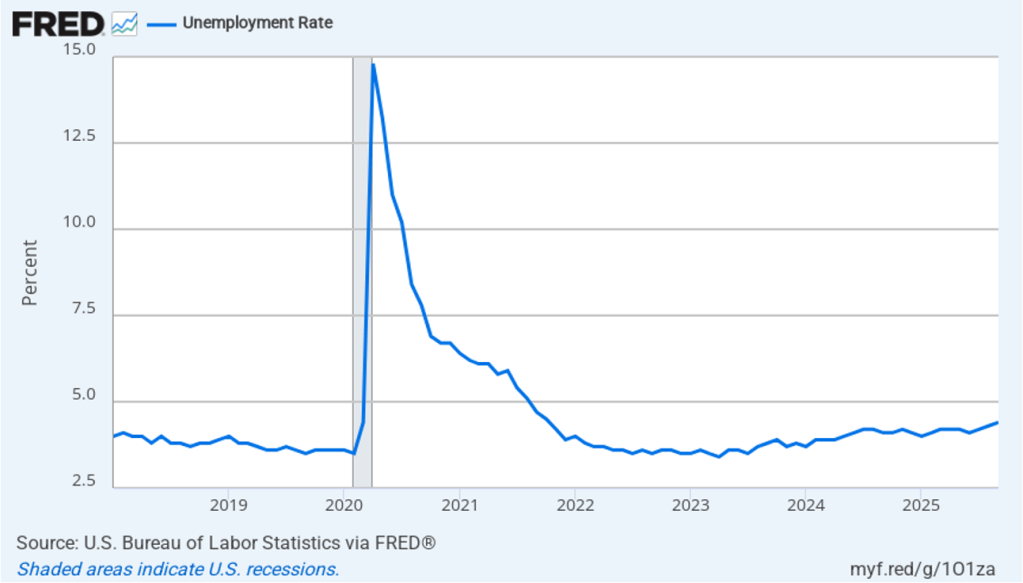

The unemployment rate decreased from 4.5 percent in November to 4.4 percent in December. The unemployment rate is below the 4.5 percent rate economists surveyed by FactSet had forecast. As the following figure shows, the unemployment rate had been remarkably stable over the past year, staying between 4.0 percent and 4.2 percent in each month May 2024 to July 2025 before breaking out of that range in August. Not that the gap in the figure for October reflects the fact that the federal government shutdown resulted in the BLS not conducting a household survey in that month.

Each month, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta estimates how many net new jobs are required to keep the unemployment rate stable. Given a slowing in the growth of the working-age population due to the aging of the U.S. population and a sharp decline in immigration, the Atlanta Fed currently estimates that the economy would have to create 113,487 net new jobs each month to keep the unemployment rate stable at 4.4 percent. If this estimate is accurate, continuing monthly net job increases of only 50,000 would result in a rising unemployment rate.

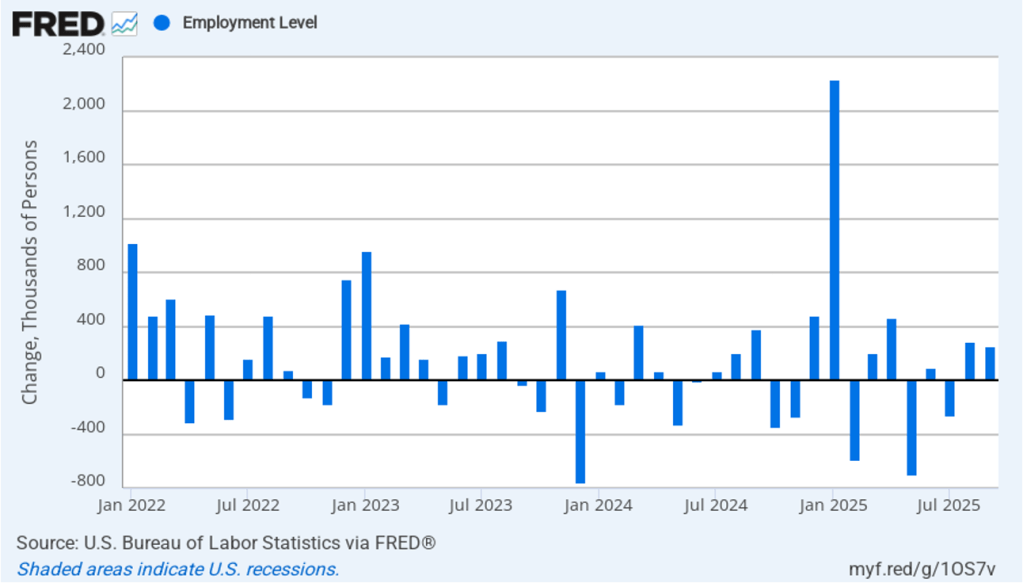

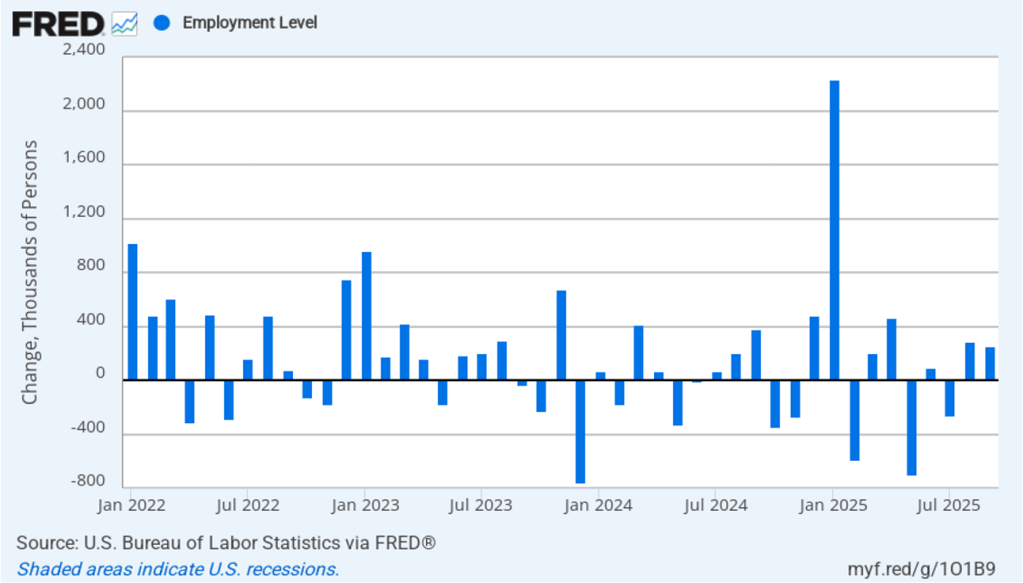

As the following figure shows, the monthly net change in jobs from the household survey moves much more erratically than does the monthly net change in jobs from the establishment survey. As measured by the household survey, there was a net increase of 232,000 jobs in December. (There is no employment estimate from the household survey for October or November.) As an indication of the volatility in the employment changes in the household survey note the very large swings in net new jobs in January and February. In any particular month, the story told by the two surveys can be inconsistent, as was the case this month with employment increasing much more in the household survey than in the employment survey. (In this blog post, we discuss the differences between the employment estimates in the two surveys.)

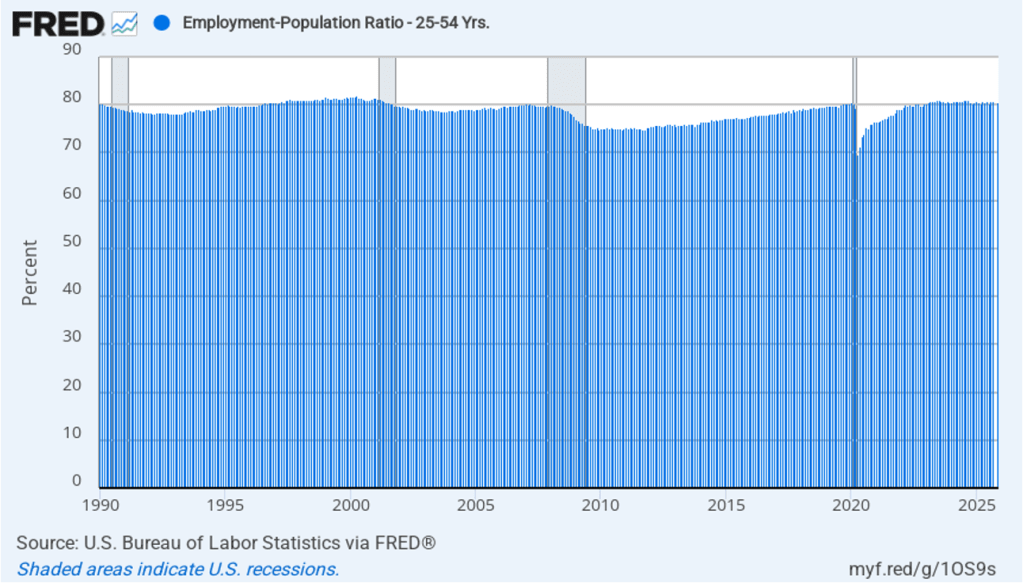

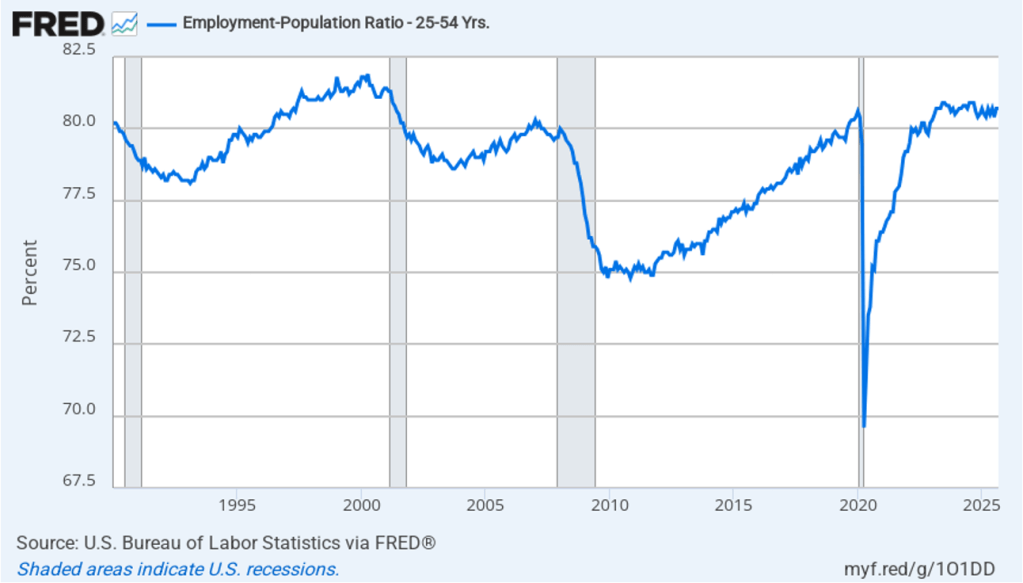

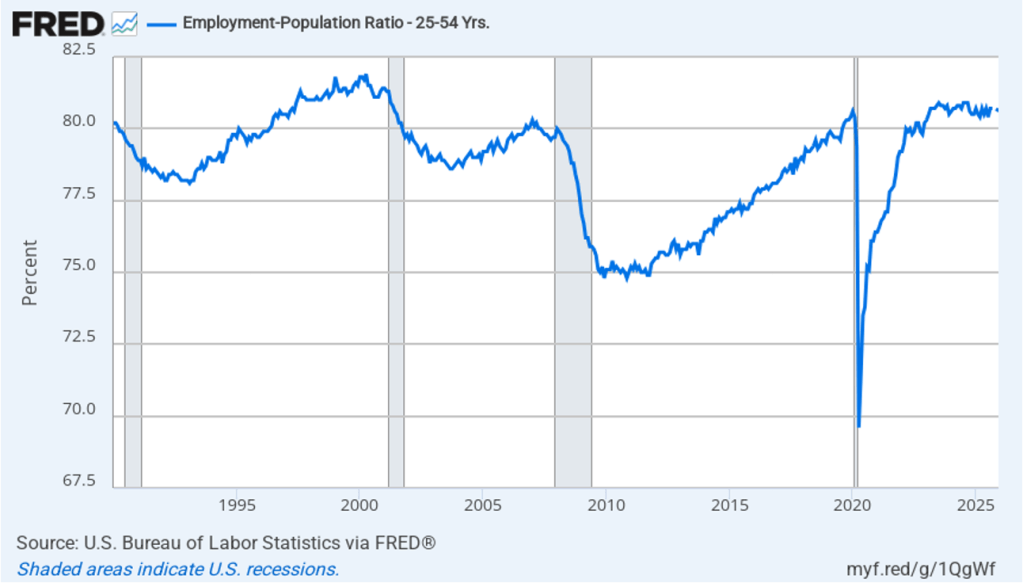

The household survey has another important labor market indicator: the employment-population ratio for prime age workers—those aged 25 to 54. In December the ratio rose to 80.7 percent from 80.6 percent in November. The prime-age employment-population ratio is somewhat below the high of 80.9 percent in mid-2024, but is still above what the ratio was in any month during the period from January 2008 to February 2020. The increase in the prime-age employment-population ratio is a particular bright spot in this month’s jobs report.

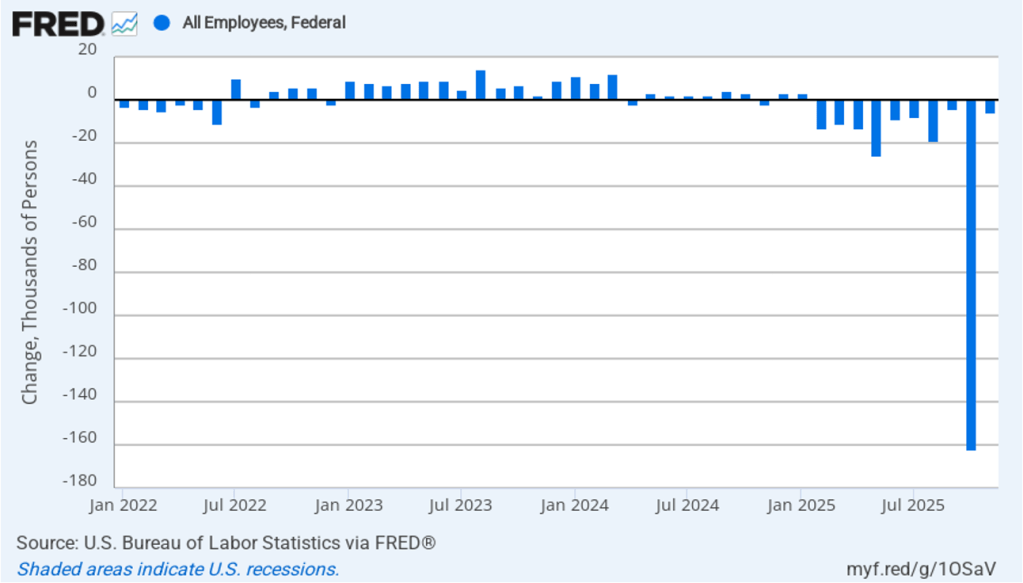

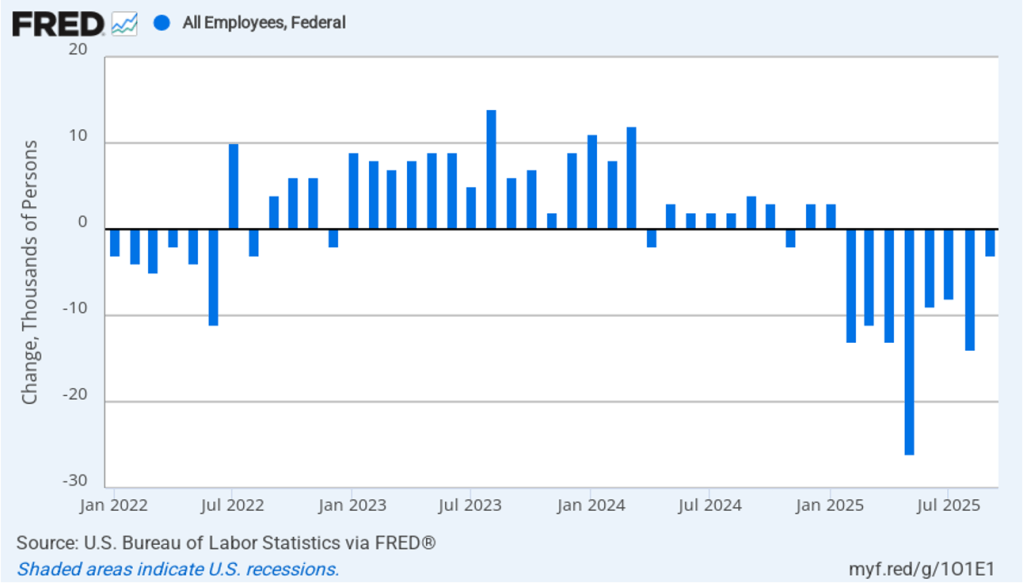

The following figure shows monthly net changes in federal government employment as measured by the establishment survey. Following the very large net decrease of 179,000 federal government jobs in October, the data for the last two months were more typical of the changes in earlier years with a net increase of 3,000 federal jobs in November and 2,000 jobs in December. In these two months, changes to federal employment had only a small effect on the overall labor market.

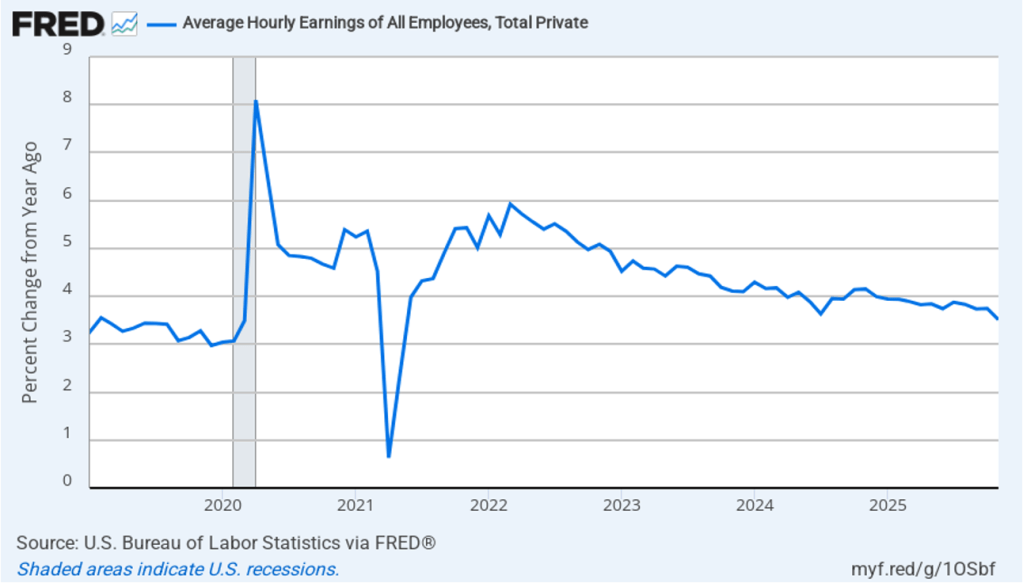

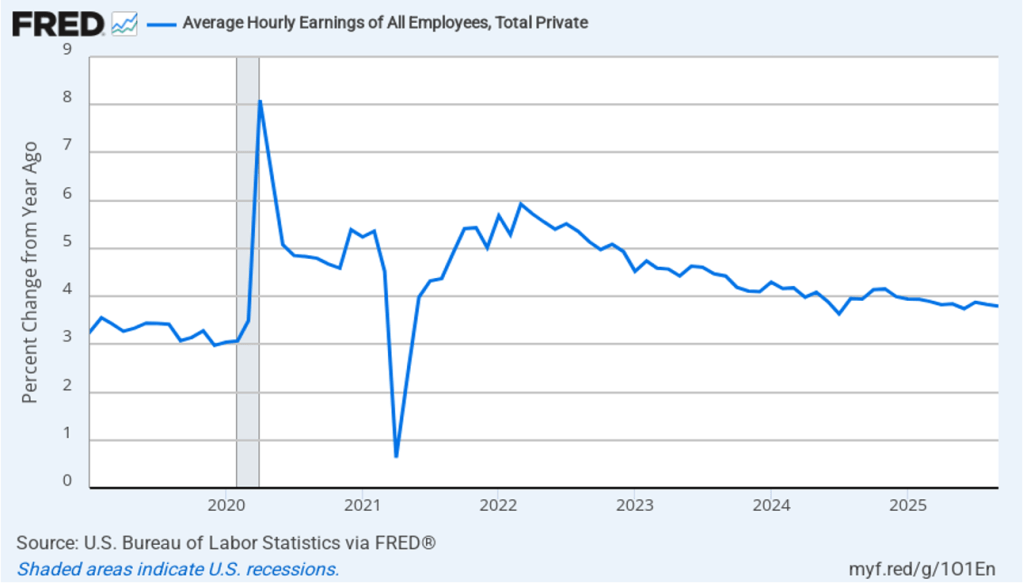

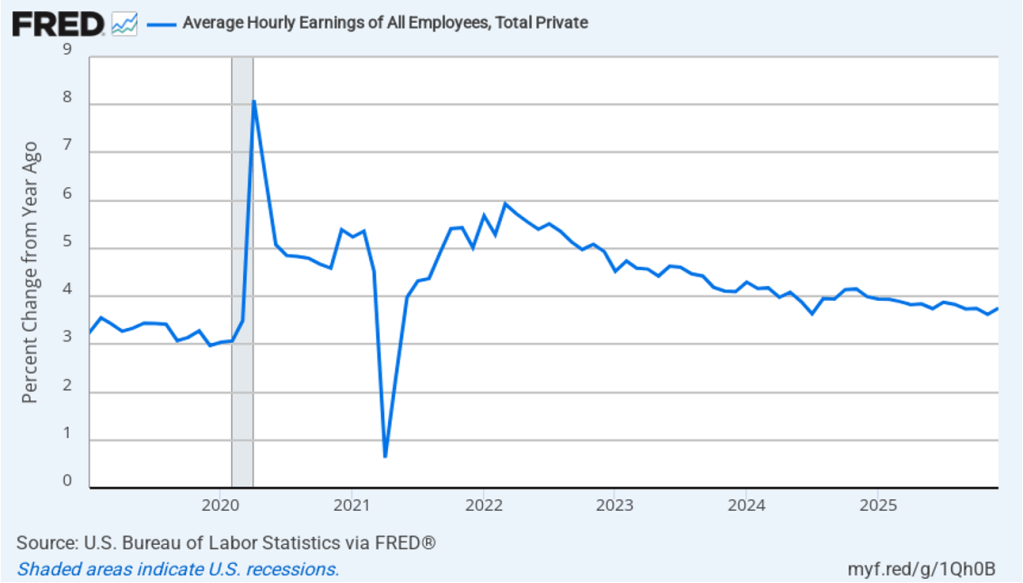

The establishment survey also includes data on average hourly earnings (AHE). As we noted in this post, many economists and policymakers believe the employment cost index (ECI) is a better measure of wage pressures in the economy than is the AHE. The AHE does have the important advantage of being available monthly, whereas the ECI is only available quarterly. The following figure shows the percentage change in the AHE from the same month in the previous year. The AHE increased 3.8 percent in December, up from an increase of 3.6 percent in November.

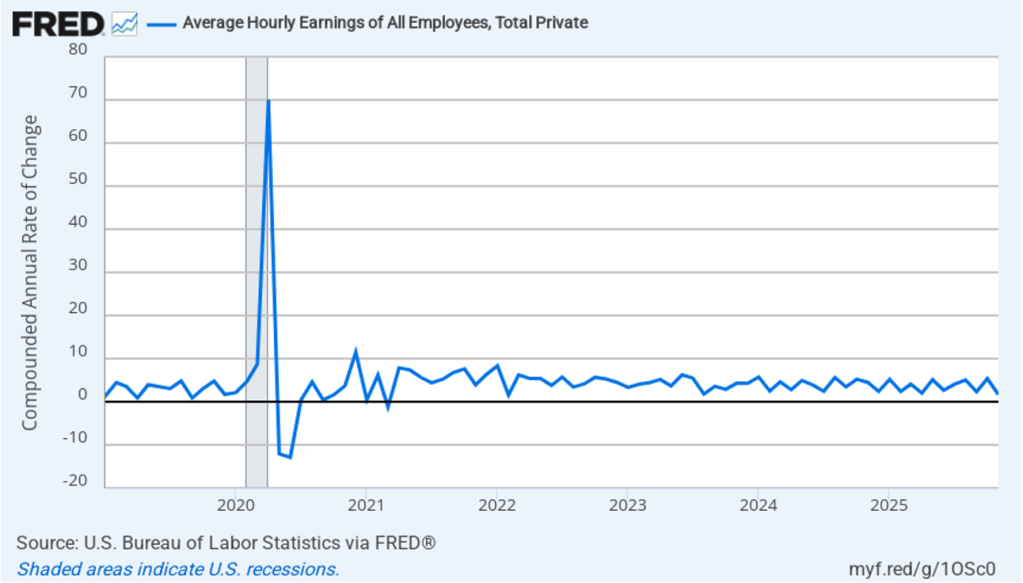

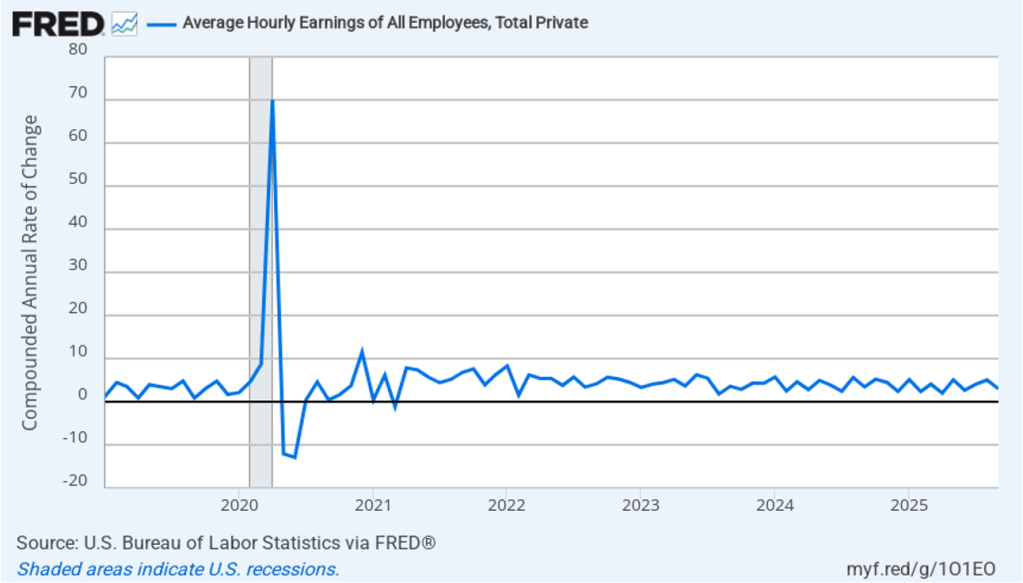

The following figure shows wage inflation calculated by compounding the current month’s rate over an entire year. (The figure above shows what is sometimes called 12-month wage inflation, whereas this figure shows 1-month wage inflation.) One-month wage inflation is much more volatile than 12-month wage inflation—note the very large swings in 1-month wage inflation in April and May 2020 during the business closures caused by the Covid pandemic. In December, the 1-month rate of wage inflation was 4.0 percent, up from 3.0 percent in November. Both the 1-month and the 12-month data for average hourly earnings show that wage growth remains fairly strong.

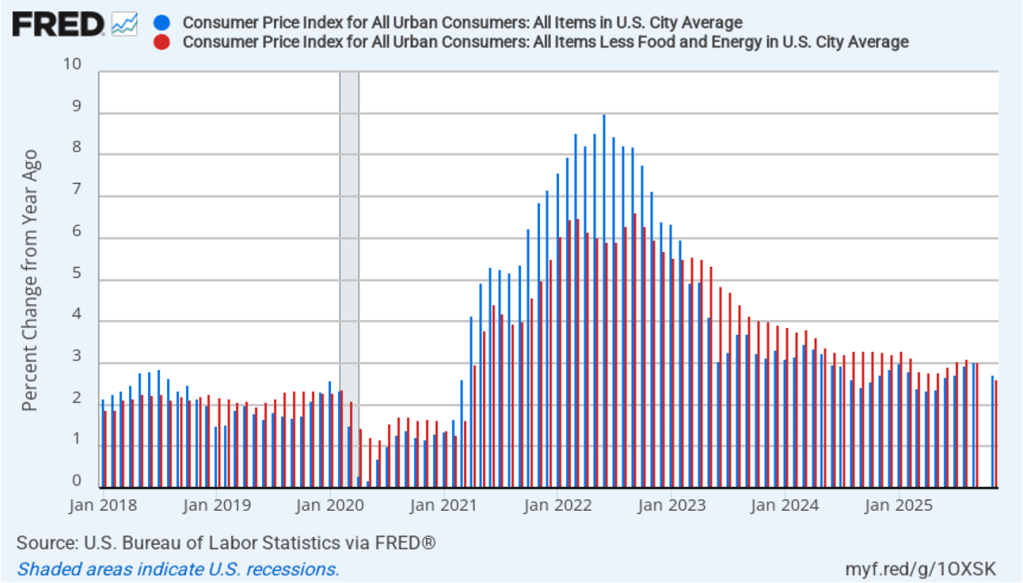

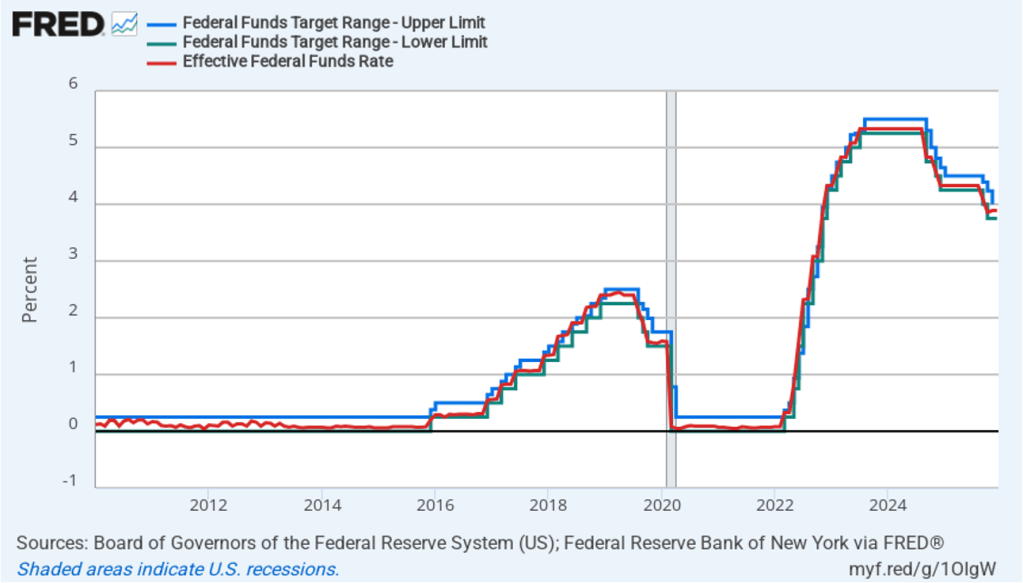

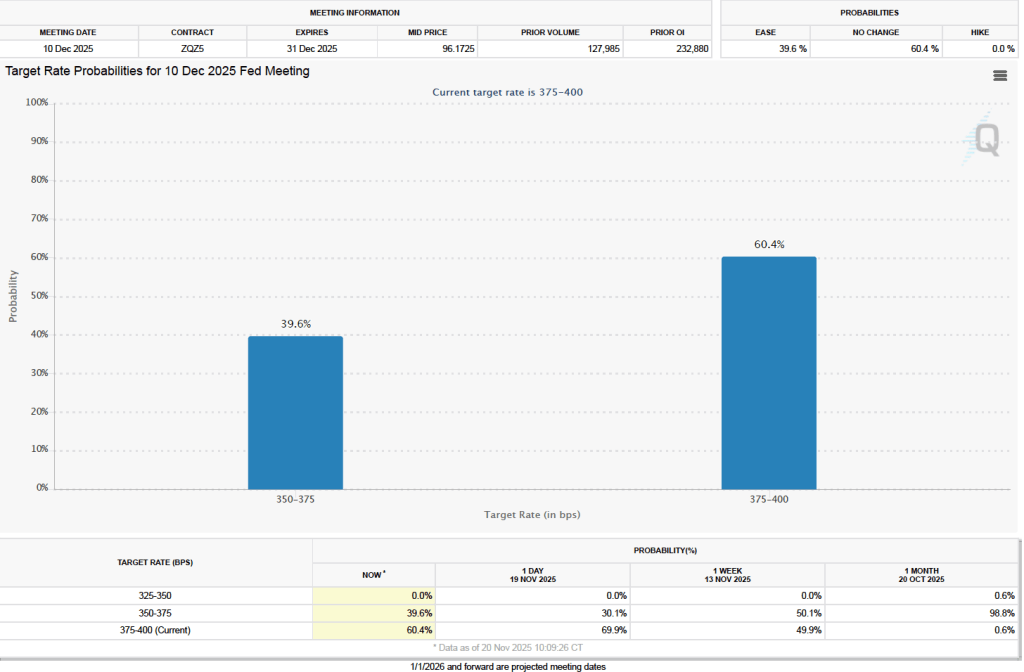

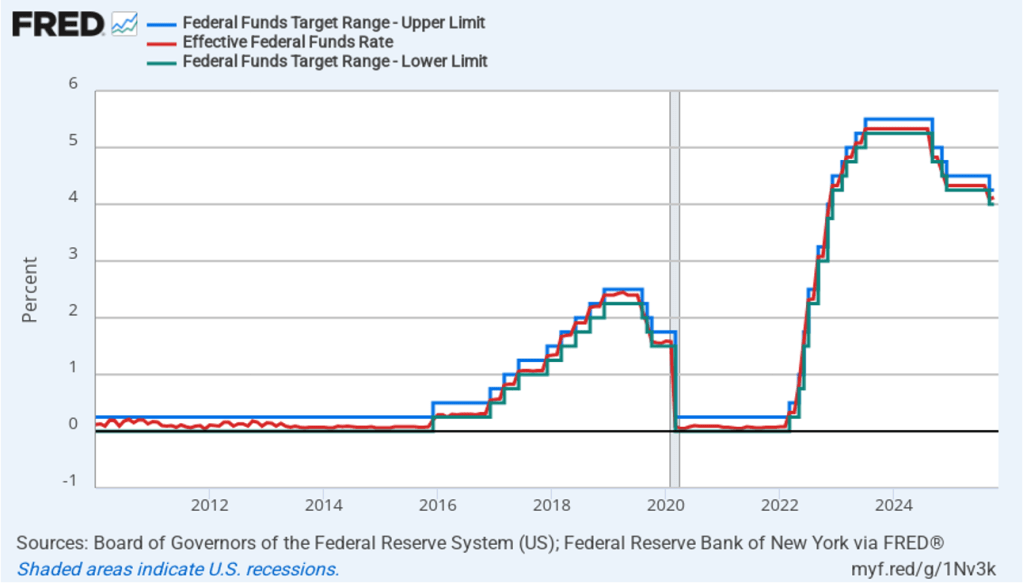

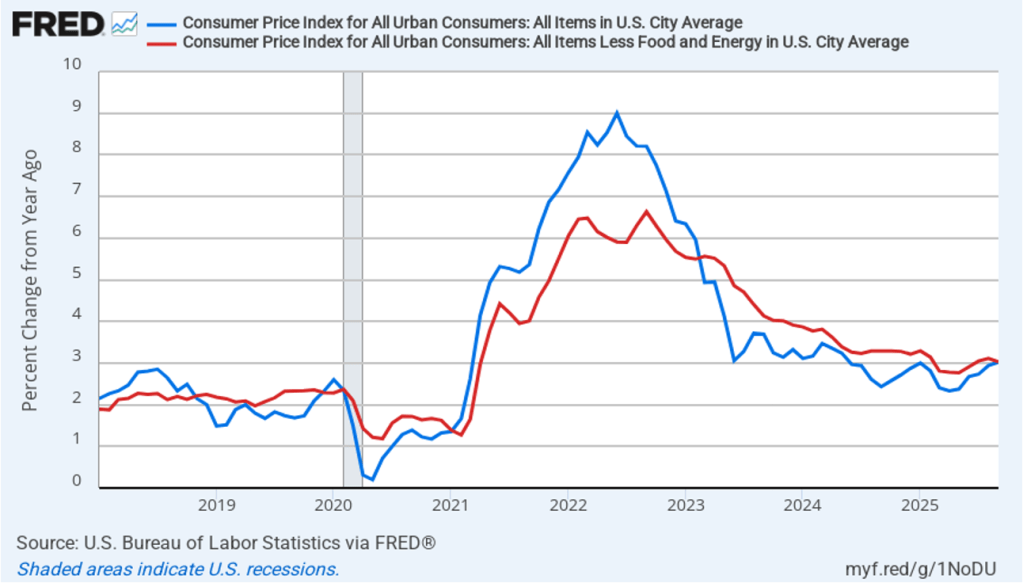

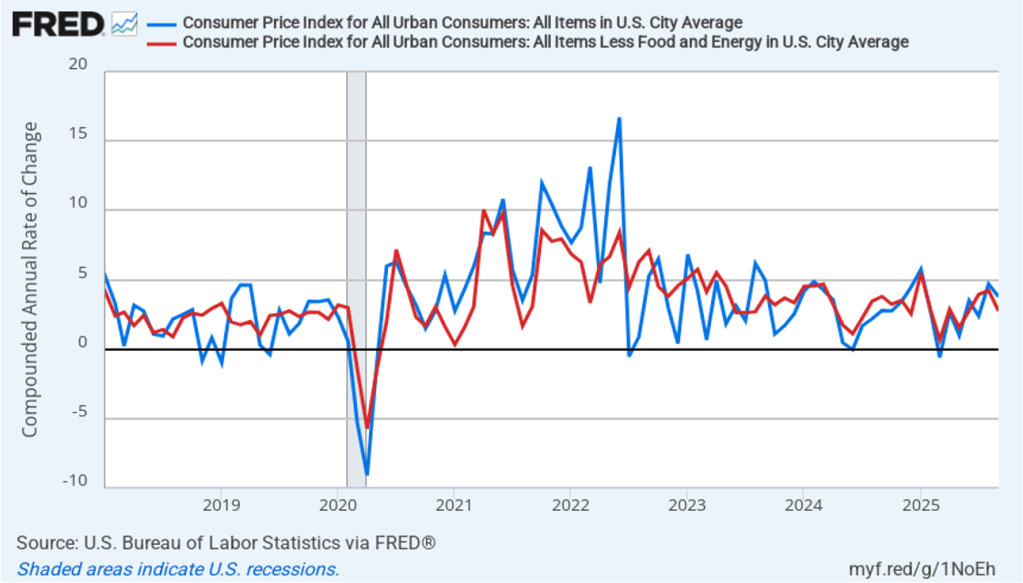

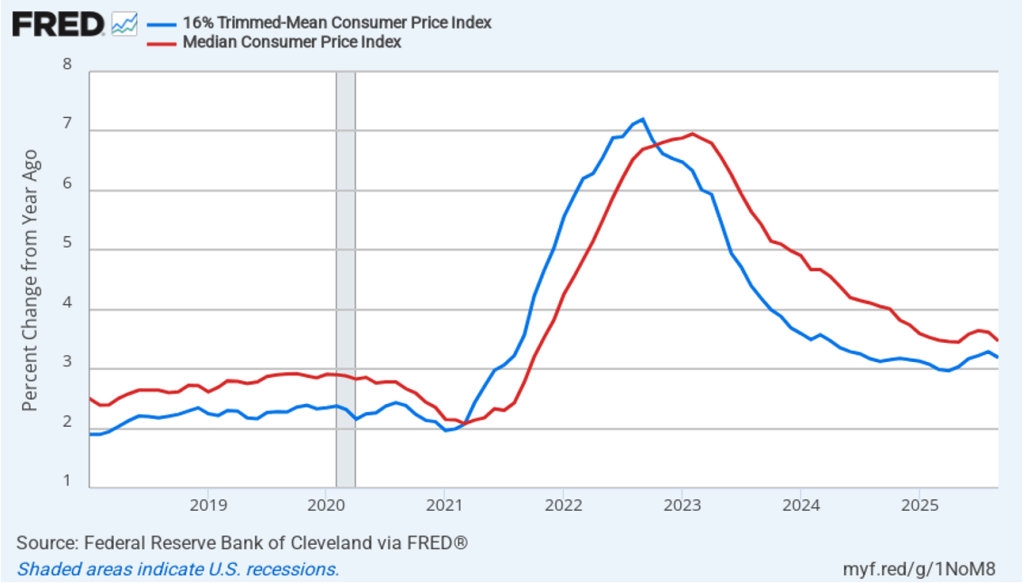

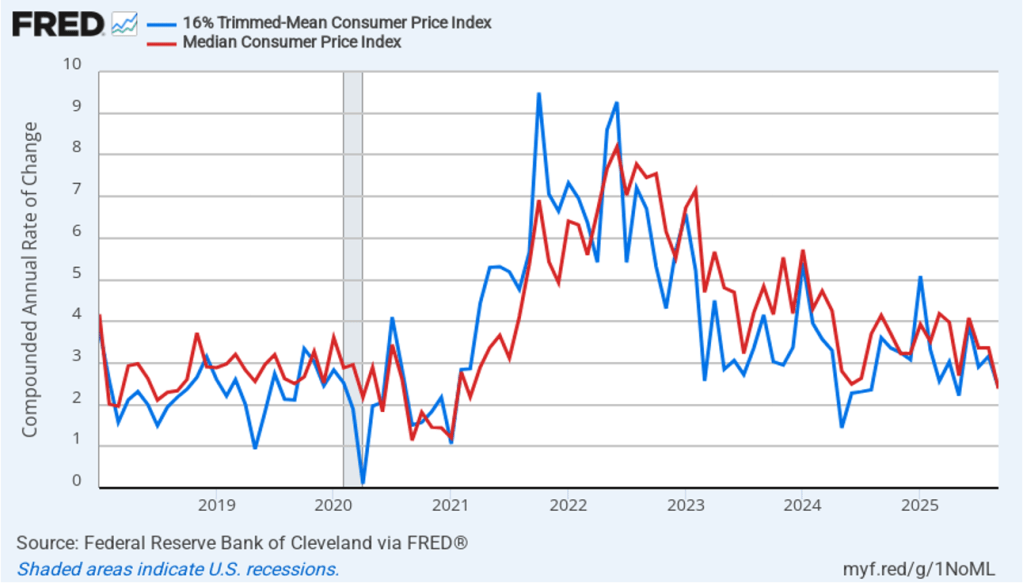

What effect might today’s jobs report have on the decisions of the Federal Reserve’s policymaking Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) with respect to setting its target for the federal funds rate? One indication of expectations of future changes in the FOMC’s target for the federal funds rate comes from investors who buy and sell federal funds futures contracts. (We discuss the futures market for federal funds in this blog post.) In recent weeks, investors have expected that the FOMC would leave its target for the federal funds rate unchanged at its next meeting on January 27–28. This afternoon, as the following figure shows, investors raised the probability they assign to the committee leaving its target for the federal funds rate unchanged to 95.0 percent from 88.9 percent yesterday. The relatively strong jobs report combined with measures of inflation remaining above the Fed’s 2 percent annual target, makes it likely that the committee will wait to receive additional data on employment, inflation, and GDP before adjusting its federal funds rate target.