Image generated by GTP-4o of someone in Germany working on a spreadsheet

Supports: Macroeconomics, Chapter 18, Section 18.2; and Economics, Chapter 28, Section 28.2.

A column in the New York Times made the following observations:

“The greenback has been climbing since Trump’s victory, a potential drag on multinationals’ profits. Elsewhere, the yield on the closely watched 10-year Treasury note ticked higher again on Tuesday ….”

- What is a “greenback”? What does it mean to say that the greenback has been “climbing”? Climbing relative to what?

- Is there a connection between the interest rate on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note increasing and the value of the greenback increasing? Briefly explain.

- Why would an increase in the value of the greenback be a potential drag on the profits of U.S.-based multinationals?

Solving the Problem

Step 1: Review the chapter material. This problem is about the effect of changes in the ex-change rate, so you may want to review the section “The Foreign Exchange Market and Exchange Rates.”

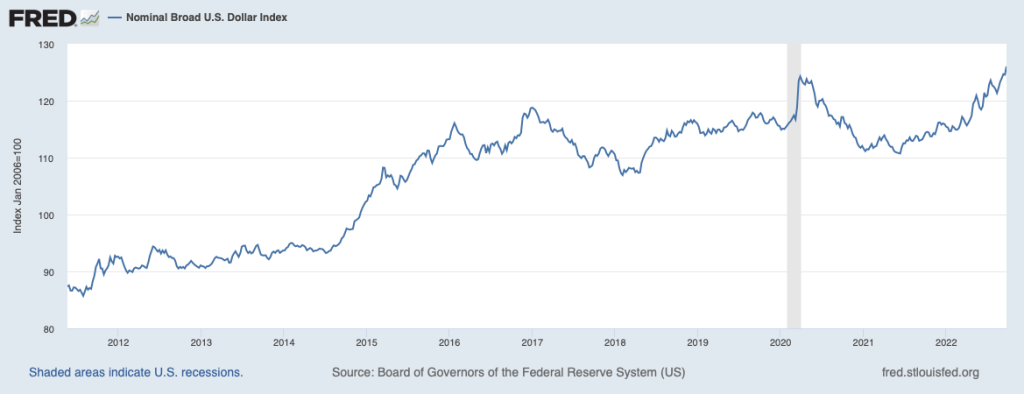

Step 2: Answer part (a) by explaining what a greenback is and what it means to say that the greenback is climbing. “Greenback” is a slang term for the U.S. dollar because the back of U.S. currency is printed in green ink. The “greenback climbing” means that the U.S. dollar is increasing in value relative to other currencies—in other words, the exchange rate is increasing.

Step 3: Answer part (b) by explaining whether there is a connection between the value of the U.S. dollar increasing as the interest rate on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note is increasing. There is a connection: Higher interest rates in the United States will make investing in U.S. financial securities, such as Treasury notes, more attractive to foreign investors. Foreign investors will increase their demand for dollars, increasing the equilibrium exchange rate.

Step 3: Answer part (c) by explaining why an increase in the value of the greenback will affect the profits of U.S. multinational corporations. A U.S. multinational firm, such as Microsoft or Apple, will have operations in other countries. When, for instance, Microsoft sells access to its Office Suite to customers in France of Germany, the customers pay in euros. If the value of the dollar has risen in exchange for euros, when Microsoft converts the euros into dollars it receives fewer dollars, thereby reducing its profits.