Join authors Glenn Hubbard and Tony O’Brien as they discuss how core economic principles illuminate two of the most pressing policy debates facing the economy today: tariffs and artificial intelligence. Drawing on a recent Supreme Court decision striking down broad tariff increases, Hubbard and O’Brien explain why economists view tariffs as taxes, who ultimately bears their burden, and how trade policy uncertainty shapes business decisions, inflation, and economic growth—bringing textbook concepts like tax incidence, intermediate goods, and GDP measurement vividly to life. The conversation then turns to AI, where they cut through market hype and dire predictions to place generative AI in historical context as a general‑purpose technology, comparing it to past innovations that transformed jobs without eliminating work. Along the way, they explore how AI can both substitute for and complement labor, why fears of mass unemployment are likely overstated, and what economists can—and cannot yet—say about AI’s long‑run effects on productivity, profits, and the labor market.

Category: Microeconomics

How Many Manufacturing Workers Are There in the United States?

Image created by ChatGPT

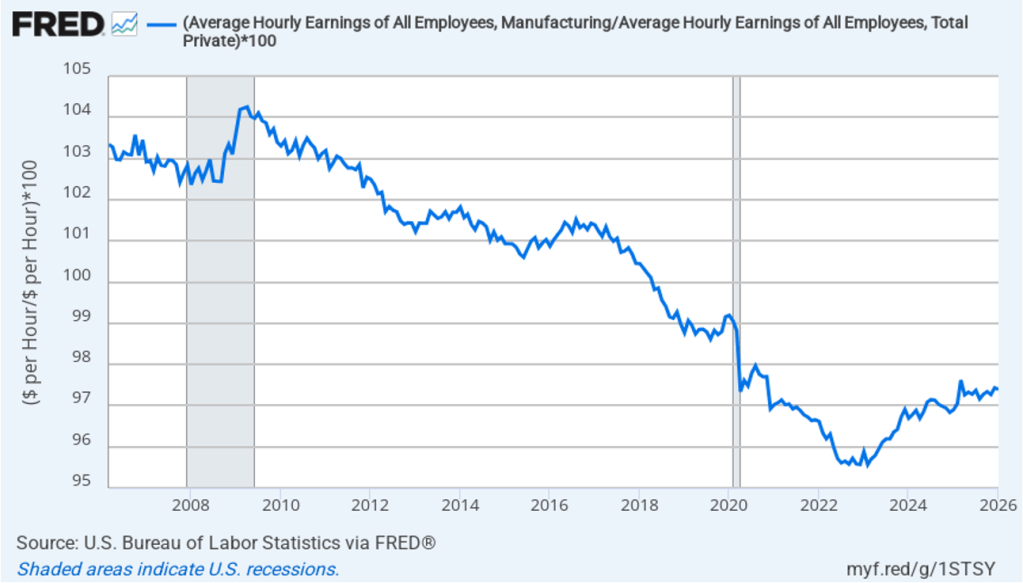

Every president dating back to at least Ronald Reagan, who took office in January 1981, has promised to increase manufacturing employment. Manufacturing jobs are often seen as making it possible for workers without a college degree to earn a middle-class income. As the following figure shows, though, since 2018, average hourly earnings of workers in manufacturing have actually been less than average hourly earnings of all workers.

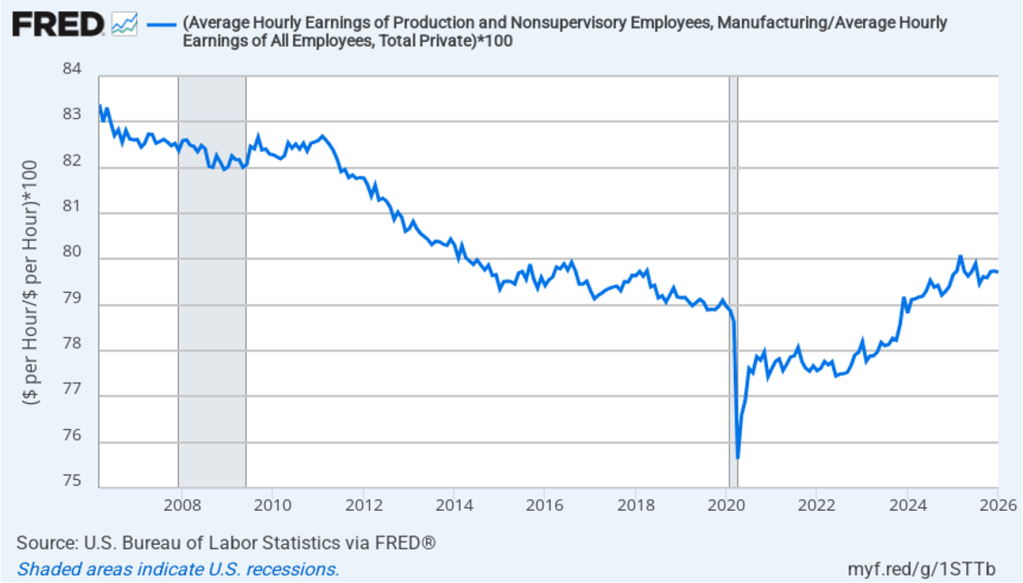

If we look at just the wages of production and nonsupervisory workers in manufacturing—like the workers shown in the image above—during the past 20 years, the average hourly earnings of production workers in manufacturing have generally been about 20 percent less than the average hourly earnings of all workers.

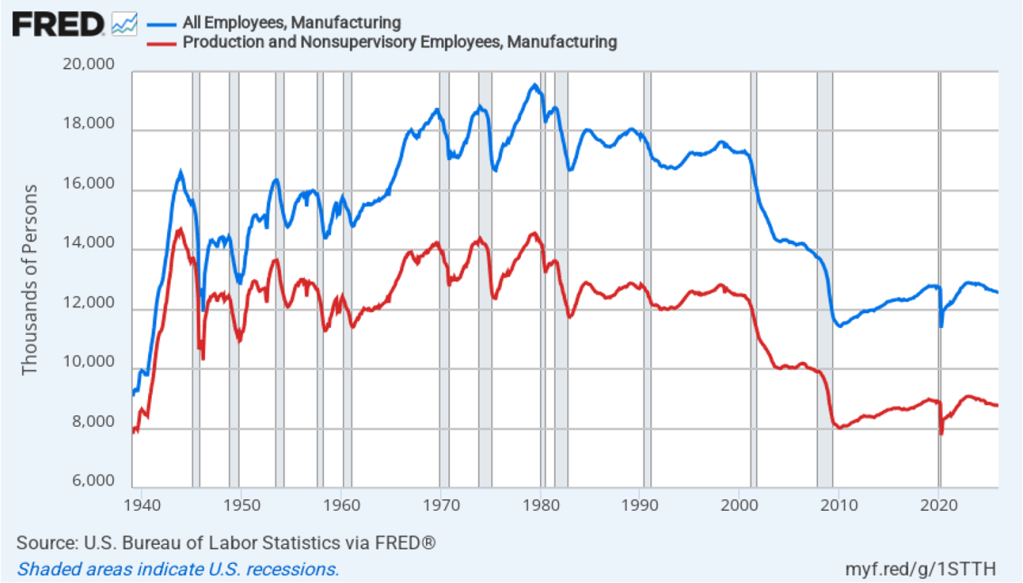

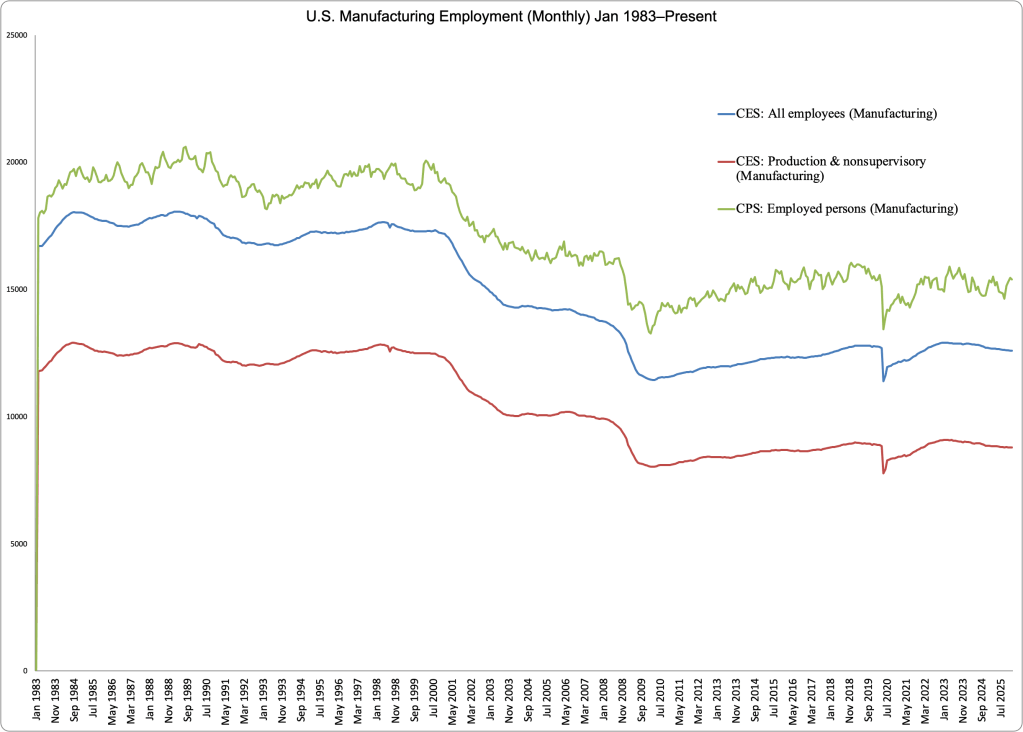

The following figure shows the absolute number of all employees in manufacturing (the blue line) and production and nonsupervisory employees in manufacturing monthly since 1939. Employment of production workers peaked in 1943, during World War II. Employment of all employees in manufacturing peaked in 1979. (All employees in manufacturing include, in addition to production workers, managers and other employees with administrative duties, accountants, lawyers, salespeople, and all other employees not directly concerned with production.) The trend in manufacturing employment has generally been downward since 1979 and has been below 13 million every month since December 2008. In January 2026, there were 12.6 million total employees in manufacturing of whom 8.8 million were production workers.

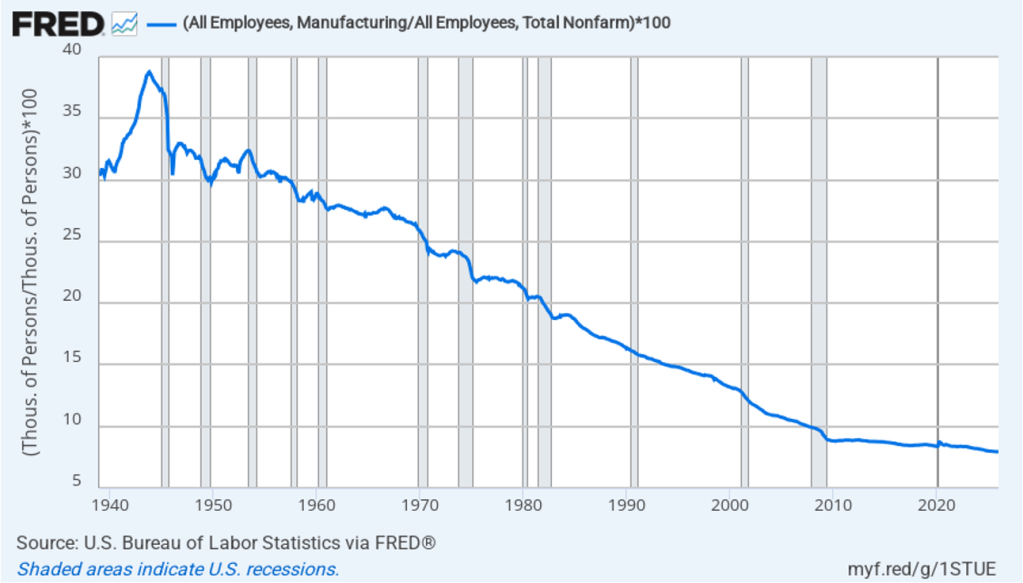

The following figure shows manufacturing employment as a percentage of total employment for each month since 1939. Manufacturing employment peaked as percentage of total employment at 38.7 percent in 1943. It has slowly trended down since that time, being below 10 percent every month since September 2007. In January 2026, manufacturing employment was 7.9 percent of total employment.

All of the data in the figurs shown so far are from the establishment survey (formally, the Current Employment Statistics (CES)). Recently, Adam Ozimek, Benjamin Glasner, and Jiaxin He of the Economic Innovation Group have examined the discrepancy between the number of manufacturing workers as reported in establishment survey and the larger number of manufacturing workers reported in the household survey (formally, the Current Population Survey (CPS).) Each month when the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) releases its “Employment Situation” report, usually referred to as the “jobs report,” attention focuses on two numbers: The change in total employment as calculated from the establishment survey and the unemployment rate as calculated from the household survey.

In addition to the unemployment rate, the BLS releases monthly data on total employment and on employment by industry from the household survey. Most economists, policymakers, and investment analysts pay little attention to the data on employment by industry from the household survey because the employment by industry data from the establishment survey is considered more reliable. In fact, the employment by industry data from the household survey isn’t included among the many macro series available on the FRED site. The following figure reproduces the two establishment survey (CES) data (the blue and red lines) shown in the third figure above along with the household survey (CPS) data (the green line) from the BLS site. (Note that the household survey data is choppier than the data in the other two series because it is not seasonally adjusted.)

Manufacturing employment is consistently larger in the household survey data than in the establishment survey data. For example, in January 2026, total manufacturing employment according to the establishment survey was 12.6 million, whereas total manufacturing employment according to the household survey was 15.4 million—a difference of 2.7 million. Put another way, if the household survey is accurate, manufacturing employment is actually 20 percent higher than it appears from the widely-used establishment survey data.

The establishment survey data is collected by surveying firms, whereas the household survey data is collected from surveying workers. In other words, in January, 2.7 million more workers considered themselves to be in manufacturing than firms reported were actually working in manufacturing. Typically, economists and policymakers consider results from the establishment survey to be more reliable because firms are legally obliged to keep accurate accounts of the number of their employees, whereas the answers from workers responding to surveys are accepted without additional checking.

Ozimek, Glasner, and He note that the persistence of a gap between the establishment and household data on manufacturing employment indicates that there are some establishments that the census considers to be engaged in some activity other than manufacturing but whose workers consider themselves to be in manufacturing. The authors present a careful discussion of the issues involved and the entire piece (linked to above) is worth reading carefully by anyone who is concerned about this issue, but we can mention here one particularly interesting point.

The authors link to a paper by Andrew Bernard and Theresa Fort of Dartmouth College discussing “factoryless goods producing firms,” which are “manufacturing-like as they perform many of the tasks and activities found in manufacturing firms” but that don’t actually manufacture goods. Ozimek, Glasner, and He give as one example Apple’s Elk Grove, California site. They note that at one time Apple assembled computers at that site but that currently “there is no assembly at that location, but thousands of Apple employees work there on logistics, distribution, repair, and customer support.” In other words, the site contributes to manufacturing Apple’s products and, if surveyed, many of its employees might respond that they work in manufacturing, but because no products are actually assembled at the site, the site won’t be considered as engaged in manufacturing by the establishment survey. They conclude that: “These sorts of employees—who work adjacent to manufacturing, but not in categorized establishments—make up a big chunk of the 2.2 to 2.8 million missing manufacturing workers.”

Clearly, an important issue in an accurate count of manufacturing workers is a definition of what we mean by manufacturing. Should a particular site—establishment—be considered as engaged in manufacturing only if products are assembled at that site? Or should a site be considered as engaged in manufacturing if its purpose is to support assembly that is done elsewhere?

Because the number of manufacturing workers and the fraction of the labor force engaged in manufacturing have been important political issues for decades, it’s somewhat surprising how little attention has been devoted to ensuring that we’re actually correctly measuring manufacturing employment.

New Real GDP Data Shows that Growth Slowed Substantially in the Fourth Quarter … or Did It?

Image created by ChatGPT

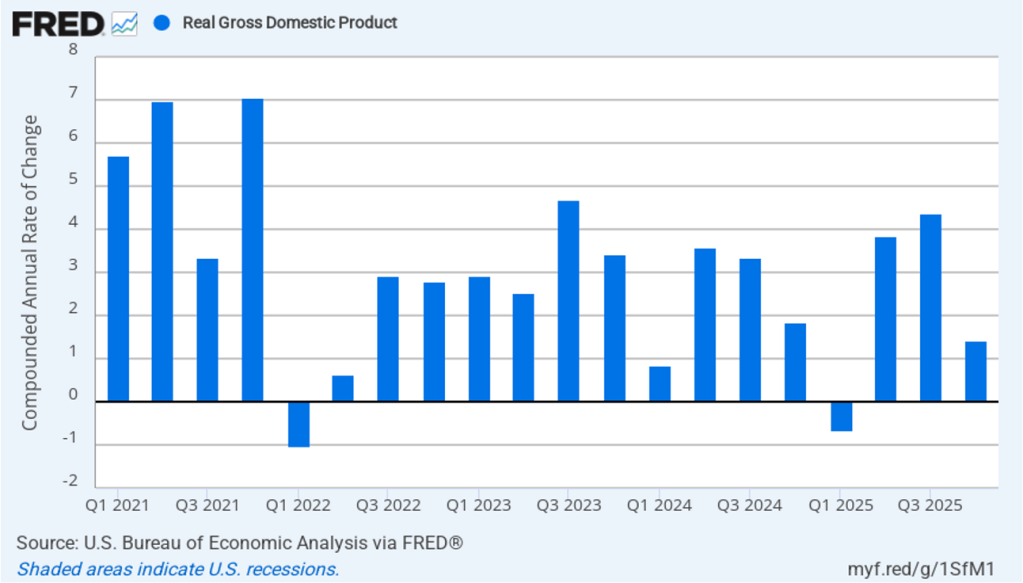

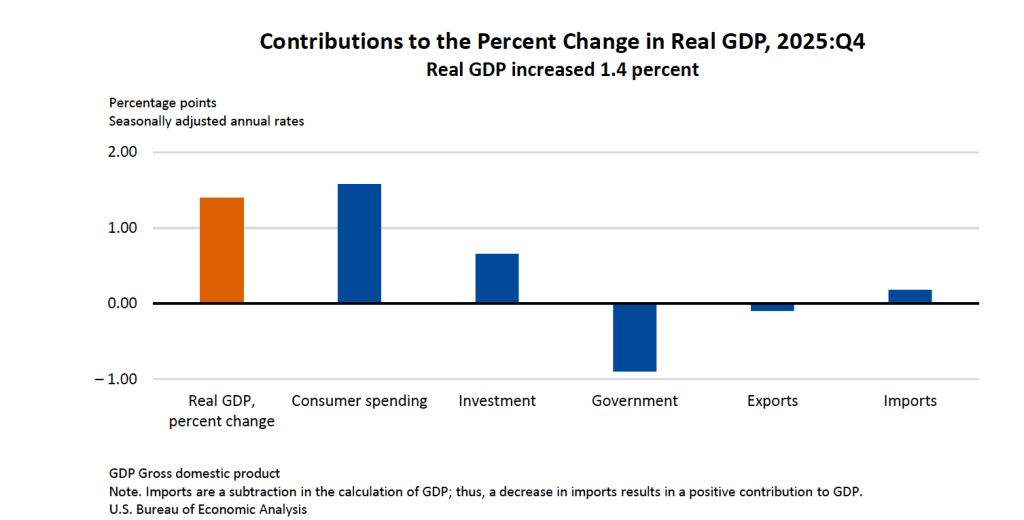

Recent macro data had been showing relatively strong growth in output and steady growth in employment. This morning’s release of the initial estimate of real GDP growth for the fourth quarter of 2025 from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) was expected to show continuing solid growth. (The report can be found here.) Instead, the BEA estimates that real GDP increased in the fourth quarter by only 1.4 percent measured at an annual rate. Growth was down sharply from the 4.4 percent increase in the third quarter of 2025. Economists surveyed by the Wall Street Journal had forecast a 2.5 percent increase. The following figure shows the estimated rates of GDP growth in each quarter beginning with the first quarter of 2021.

As the following figure—taken from the BEA report—shows, the decline in real government expenditures of –0.90 percent at an annual rate was the most important factor contributing to the slowing growth in real GDP during the fourth quarter. The decline in government expenditures is largely attributable to the federal government shutdown, which lasted from October 1, 2025 to November 12, 2025.

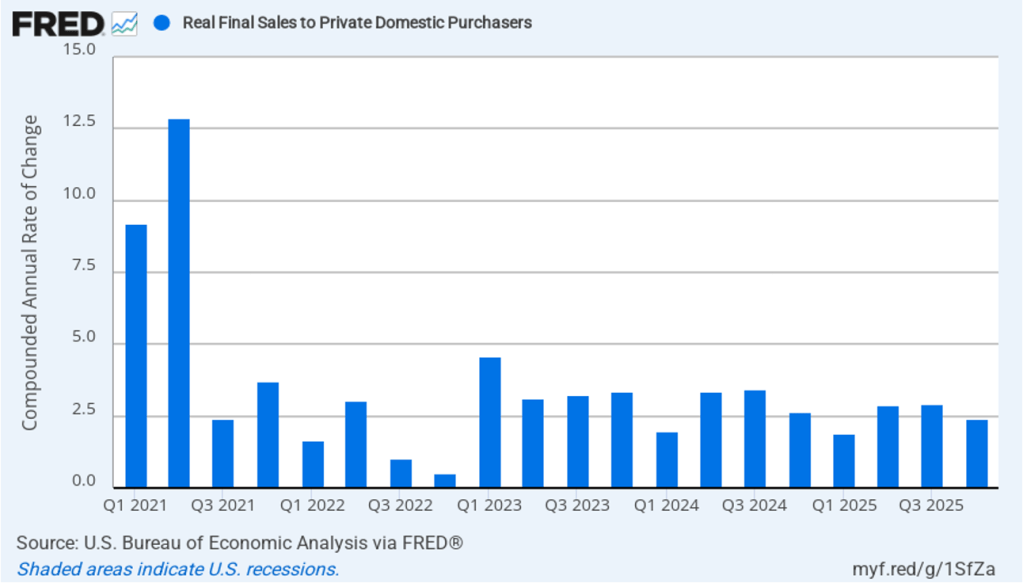

As we’ve discussed in previous blog posts, to better gauge the state of the economy, policymakers—including Fed Chair Jerome Powell—often prefer to strip out the effects of imports, inventory investment, and government expenditures—which can be volatile—by looking at real final sales to private domestic purchasers, which includes only spending by U.S. households and firms on domestic production. As the following figure shows, real final sales to domestic purchasers increased by 2.4 percent at an annual rate in the fourth quarter, which was well above the 1.4 percent increase in real GDP and also above the U.S. economy’s expected long-run annual real growth rate of 1.8 percent. Note also that real final sales to private domestic purchasers grew by 2.9 percent in the third quarter, during which real GDP grew by 4.4 percent, and by 1.9 percent in the first quarter of 2025, when real GDP declined by 0.6 percent. So this measure of output is more stable and likely is a better indicator of the underlying growth rate in the economy than is growth in real GDP.

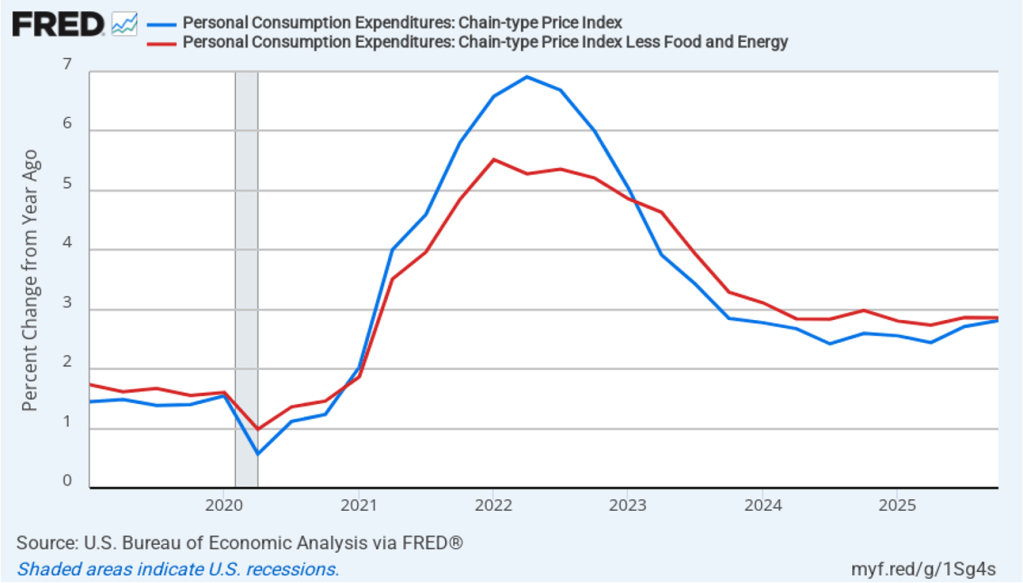

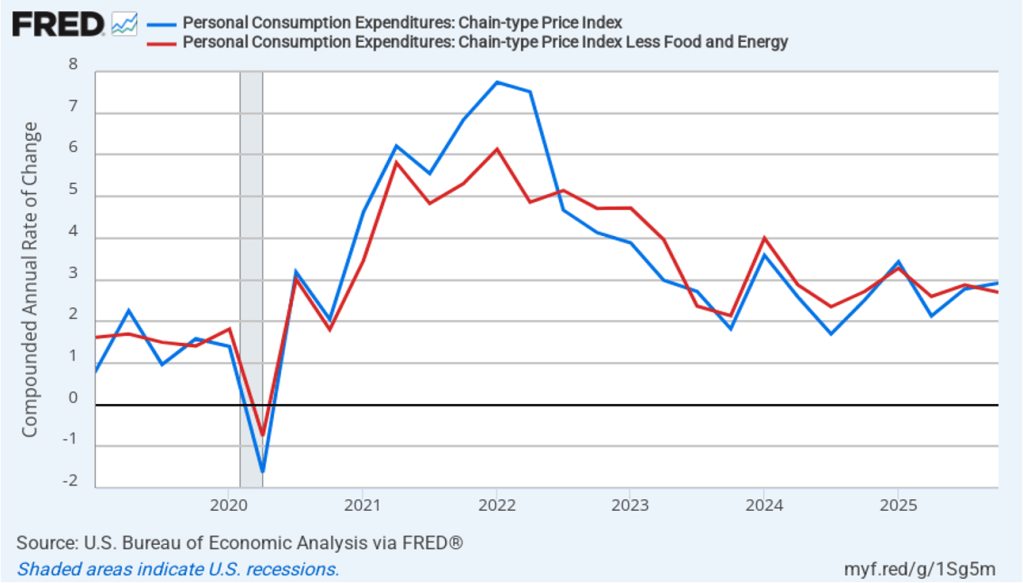

The BEA report this morning also included quarterly data on the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index. The Fed relies on annual changes in the PCE price index to evaluate whether it’s meeting its 2 percent annual inflation target. The following figure shows headline PCE inflation (the blue line) and core PCE inflation (the red line)—which excludes energy and food prices—for the period since the first quarter of 2019, with inflation measured as the percentage change in the PCE from the same quarter in the previous year. In the fourth quarter of 2025, headline PCE inflation was 2.8 percent, up slightly from 2.7 percent in the third quarter. Core PCE inflation in the third quarter was 2.9 percent, unchanged from the third quarter. Both headline PCE inflation and core PCE inflation remained above the Fed’s 2 percent annual inflation target.

The following figure shows quarterly PCE inflation and quarterly core PCE inflation calculated by compounding the current quarter’s rate over an entire year. Measured this way, headline PCE inflation increased to 2.9 percent in the fourth quarter of 2025, up from to 2.8 percent in the third quarter. Core PCE inflation fell to 2.7 percent in the fourth quarter of 2025 from 2.9 percent in the third quarter. Measured this way, both core and headline PCE inflation were also above the Fed’s target.

Today was also notable for a decision from the U.S. Supreme Court that invalidated some of the Trump administration’s tariff increases that began to be implemented in April 2025. President Trump announced this afternoon that he would impose a new 10 percent across-the-board tariff, relying on Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974, rather than on the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), which the Supreme Court ruled today did not authorize presidents to unilaterally impose tariffs.

Today’s developments appeared unlikely to have much effect on the views of the members of the Fed’s policymaking Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). The FOMC is unlikely to lower its target for the federal funds rate at its next meeting on March 17–18. The probability that investors in the federal funds futures market assign to the FOMC keeping its target rate unchanged at that meeting increased only slightly from 94.6 percent yesterday to 96.0 percent this afternoon.

Healthcare Jobs Dominate Employment Growth in the United States

Image created by ChatGPT

It’s not surprising that employment in health care has been increasing. The National Health Expenditure (NHE) Projections Model of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services estimates that the long-run income elasticity of demand for private personal health care spending is 1.58. So, a 10 percent increase in U.S. disposable personal income will result in the long run in a 15.8 percent increase in private personal health care spending. In other words, we would expect personal health care spending to become an increasing fraction of total household spending. In addition, the median age of the U.S. population has increased from 32.9 years in 1990 to a projected 40.1 years in 2025. As people age, their demand for health care increases. Finally, holding income and age constant, demand for health care has also increased as a result of the increasing effectiveness of medical care in treating disease.

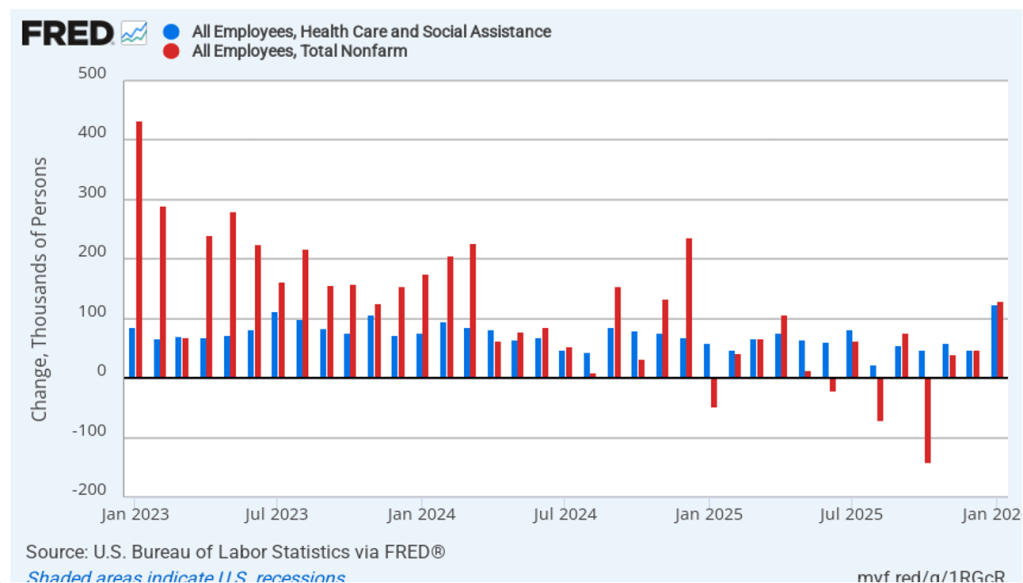

Despite these long-run trends, it’s surprising how dependent increases in U.S. employment have become recently on the growth in health care jobs. The following figure shows monthly changes in a broad measure of health care employment (the blue bars) and in total nonfarm employment (the red bars), using data from the establishment survey from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). (This blog post yesterday discussed the latest “Employment Situation” report from the BLS.)

The values for January 2023 through December 2024 show what we might expect—the increase in total employment being significantly larger than the increase in health care employment. During this period, health care employment was about 48.5 percent of total employment. In other words, although health care employment was a key driver of increases in employment, non-health care employment was also steadily increasing. The situation since January 2025 is much different with health care employment increasing by 817,000, while total employment increased by only 311,000. In other words, since January 2025, employment outside of health care (again, broadly defined) has fallen by more than 500,000 jobs.

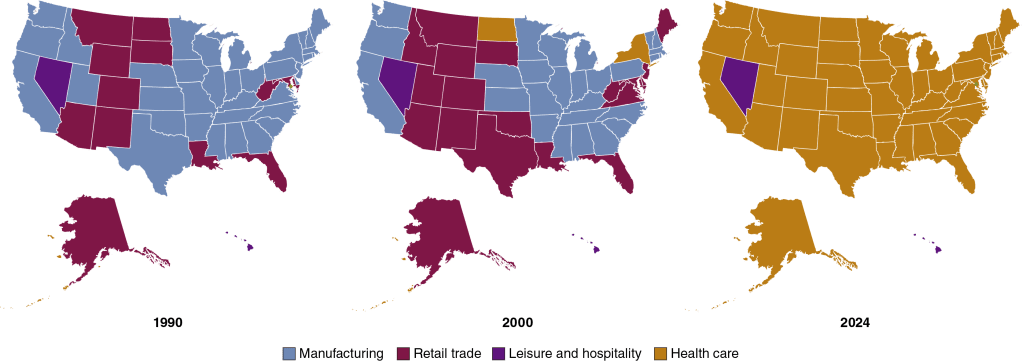

We can look at longer term trends in health care employment relative to employment in other industries. The following maps show the change over time in the industry with the most employment in each state, using data from the BLS’s “Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages.” The industries are grouped into four broad categories: manufacturing, retail trade, leisure and hospitality, and health care. (Industries are defined as follows using the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS): Manufacturing is NAICS 31–33, Retail trade is NAICS 44–45, Leisure and hospitality is NAICS 72, and health care is NAICS 62.)

In 1990, manufacturing was the largest source of private employment in most states, and in no state was health care the largest employer. By 2000, manufacturing was still the largest employer in 27 states, but health care had become the largest employer in 2 states. The results for 2024 are strikingly different: Manufacturing was no longer the largest employer in any state, and health care was the largest employer in 48 states—every state except for Hawaii and Nevada.

In 1990, almost twice as many people in the United States worked in manufacturing as worked in health care. In 2024, employment in health care was 80 percent greater than employment in manufacturing. And these trends are likely to continue. The BLS forecast in 2025 that 12 of the 20 fastest-growing occupations over the next 10 years will be in health care.

Cracker Barrel’s Dilemma: What Happens When Your Market Niche Shrinks?

Cracker Barrel’s original logo on the left and the logo it temporarily adopted in 2025 on the right. (Logos from nrn.com)

Dan Evins opened the first Cracker Barrel Old Country Store on Highway 109 in Lebanon, Tennessee in 1969 to attract more customers to his Shell service station. The restaurant offered traditional Southern-style food such as buttermilk biscuits, country-fried steak, and chicken and dumplings. Cracker Barrel was an immediate success and by 1977 had expanded to 13 locations in Tennessee and Georgia, with each location including a restaurant and an attached store designed to resemble the traditional general stores that were once common in rural areas. In 2026, Cracker Barrel had 657 locations in 44 states.

In Chapter 13, we study monopolistically competitive markets. One key feature of these markets is low barriers to entry. So we would expect that in a monopolistically competitive market such as restaurants, if an entrepreneur uses a new strategy that earns an economic profit, that strategy is likely to be copies by other firms. A number of other restaurant chains compete with Cracker Barrel offering similar menus and approaches that are intended to appeal to consumers who are older, likely to live in rural or suburban areas—particularly in the South and Midwest—and prefer traditional country-style cooking. These competitors include Golden Corral, Bob Evans, Black Bear Diner, Denny’s, and Waffle House. The entry into the market and expansion of these chains resulted in declining profits for Cracker Barrel. The chain also lost breakfast customers to IHOP, McDonald’s, and Eggs Up Grill.

In 2020, Cracker Barrel was severely affected by the Covid pandemic because many of its older customers were reluctant to eat in restaurants. Even after the effects of the pandemic had passed, Cracker Barrel’s profit continued to decline, falling from $255 million in 2021 to $40 million in 2024. In response to this falling profit, in 2024 the firm’s board of directors hired Julie Felss Masino as CEO to lead a “strategic transformation.” On being hired, Masino stated that: “We know from our research that despite high levels of consumer affinity, we’re just not as relevant as we once were. We need to address these dynamics by refreshing and refining the brand ….”

Masino oversaw a $700 million plan to transform the chain by renovating the restaurants including removing many of the vintage signs, knickknacks, tools, and photos that had decorated walls, changing the marketing approach, and updating the menu by dropping some items and adding 20 new items such as New York strip steaks, chicken sandwiches, Mimosas, and Strawberry Peach Lemonade. The aim was to attract younger and more urban customers.

Many long-time customers were opposed to changes but, overall, initially revenue and profit increased. Then in August 2025, Cracker Barrel introduced a new more streamlined and modern logo that, importantly, eliminated from the logo the drawing of an older man—often referred to as “Old Timer”—sitting on a chair with his arm on a barrel. The change led to an immediate negative response on social media from Cracker Barrel customers. The controversy was soon widely covered in the business media and elsewhere. The number of customers in Cracker Barrel’s restaurants declined by 8 percent and its stock price dropped by 40 percent as investors concluded that the firm’s rebranding was a major error that it might have difficulty coming back from.

After only a week, Masino and other company executives reversed course and reverted to using the older logo. The company also suspended the plan to remodel its restaurants and restored to its menu some items that it had dropped. Masino was quoted as stating that: “We are doubling down on delicious, scratch-made food the way our guests expect it and that great country hospitality that we’re known for.”

Will Cracker Barrel be able to bounce back from reversing its strategy of modernizing its restaurants, its menu, and its marketing to appeal to younger urban customers? It has a difficult task. The chain was originally intended to appeal to particular market niche. As competition for consumers in that niche increased and as the number of those consumers declined, the chain was faced with a difficult choice: Either reduce costs sufficiently to remain profitable with fewer customers or change its strategy in an attempt to appeal to new customers. They chose to do some of both, making the changes discussed earlier and also cutting costs in food preparation. The cost cutting was also criticized as customers objected to such changes as making its signature biscuits in large batches rather than making them as needed and reheating green beans rather than cooking them on demand. In early 2026, the outlook for the chain didn’t appear promising.

Sources: Heather Haddon, “Now Cracker Barrel Diehards Think the Food Isn’t Up to Scratch, Either,” Wall Street Journal, December 9, 2025; Nathaniel Meyerson, “Cracker Barrel Isn’t Doomed Just Yet,” edition.cnn.com, September 13, 2025; Dee-Ann Durbin, “Cracker Barrel Is Keeping Its Old-Time Logo after New Design Elicited an Uproar,” apnews.com, August 27, 2025; Dee-Ann Durbin, “Breakfast Is Booming at US Restaurants. Is It Also Contributing to High Egg Prices?” apnews.com, February 13, 2025; Heather Haddon, “After a Bruising Year, Casual-Dining Chains Try to Stage a Comeback,” Wall Street Journal, June 20, 2025; Cracker Barrel Old Coun-try Store, “Cracker Barrel Launches Flavor Packed Summer Menu Featuring Exclusive New Beed Sting Fried Chicken, Plus More,” prnewswire.com, May 8, 2024; Joanna Fantozzi, “Cracker Bar-rel Unveils ‘Strategic Transformation’ Amid Financial Struggles,” nrn.com, May 18, 2024; Lynn and Cele Seldon, “Cracker Barrel Anniversary,” trailblazer.thousandtrails.com, September 12, 2019; “About Cracker Barrel,” crackerbarrel.com; and Cracker Barrel Old Country Store, Annual Report, various years.

The United States Typically Runs Surpluses in Services as Well as Deficits in Goods

Image created by ChatGPT

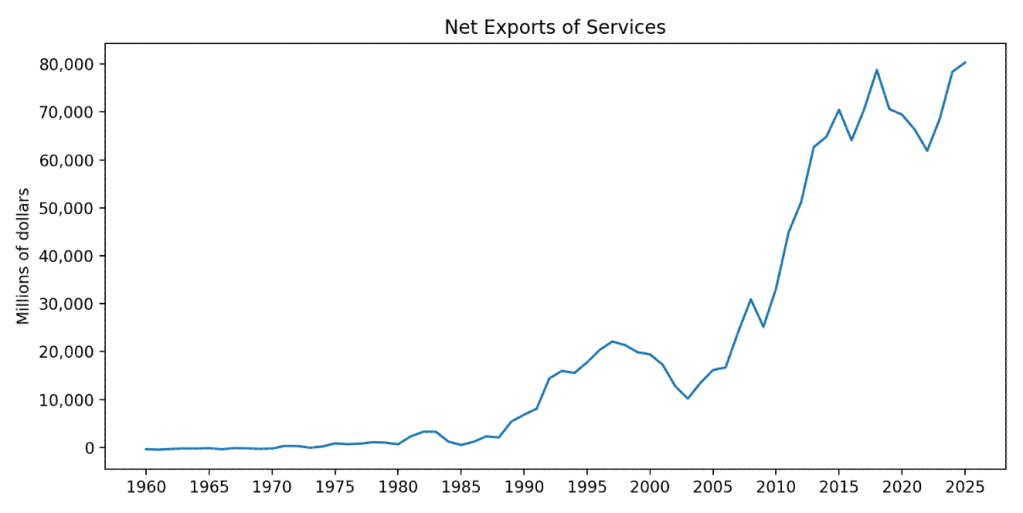

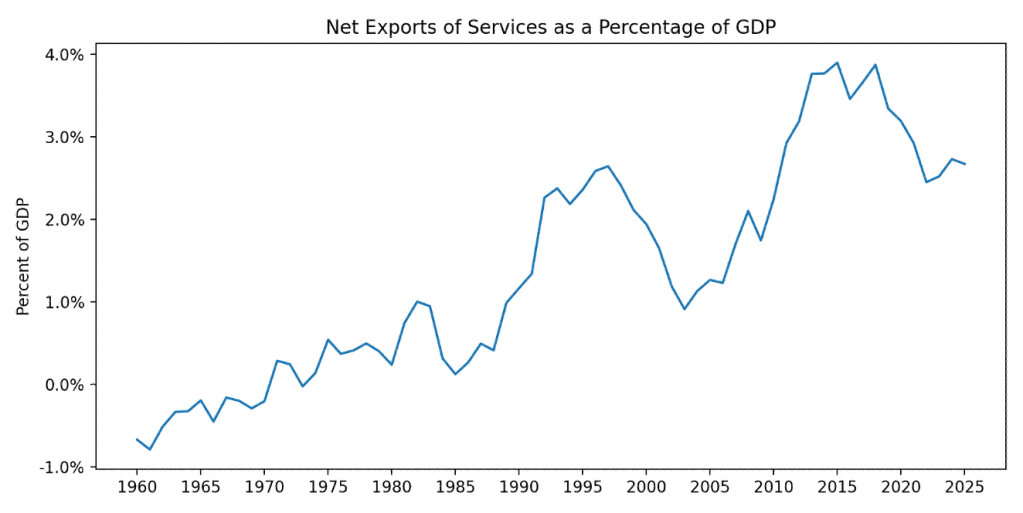

A recent post on the blog of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis reminds us that although the media and some policymakers tend to focus on the fact that the United States typically runs a deficit in trade in goods, it also typically runs a surplus in trade in services. We discuss these points in Economics, Chapter 9, Section 9.1 and Chapter 28, Section 28.1 (Macroeconomics, Chapter 7, Section 7.1 and Chapter 18, Section 18.1, and Microeconomics, Section 9.1). The first of the following figures shows U.S. net exports in services in dollar terms for the period from the first quarter of 1960 through the second quarter of 2025. The second figure show U.S. net exports in services as a percentage of U.S. GDP.

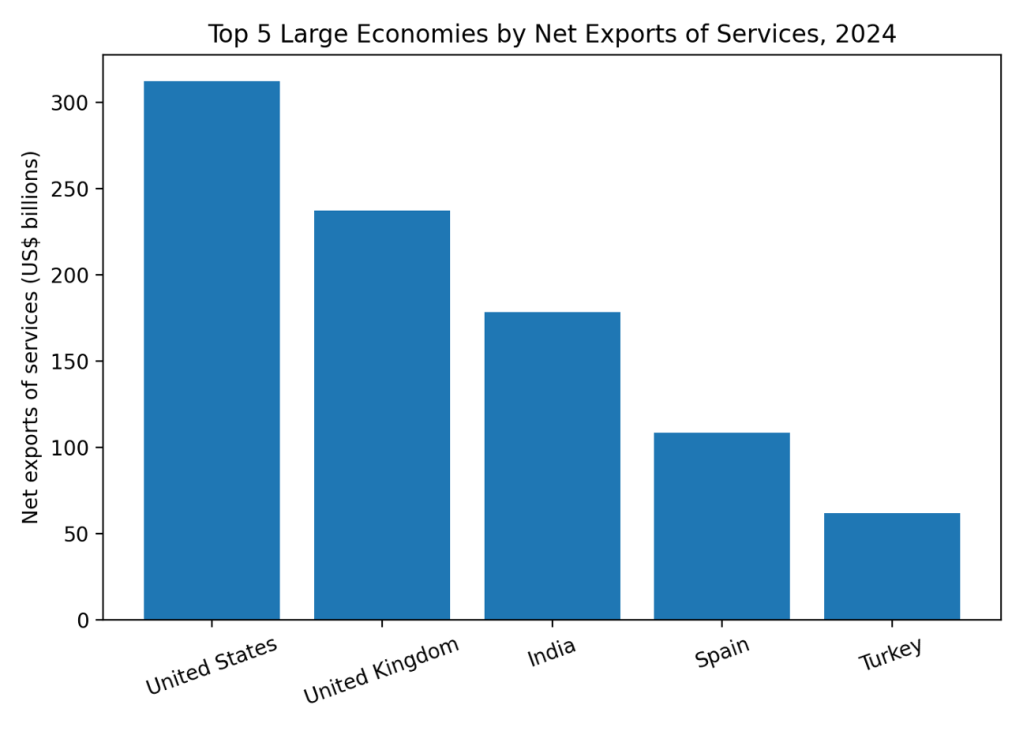

How does the United States compare to other countries? The following figure shows for 2024 the leaders in net exports of services for large economies (those with GDP of $1 trillion or more). The United States has largest value for net exports of services followed by the United Kingdom. China had negative net exports of services in 2024.

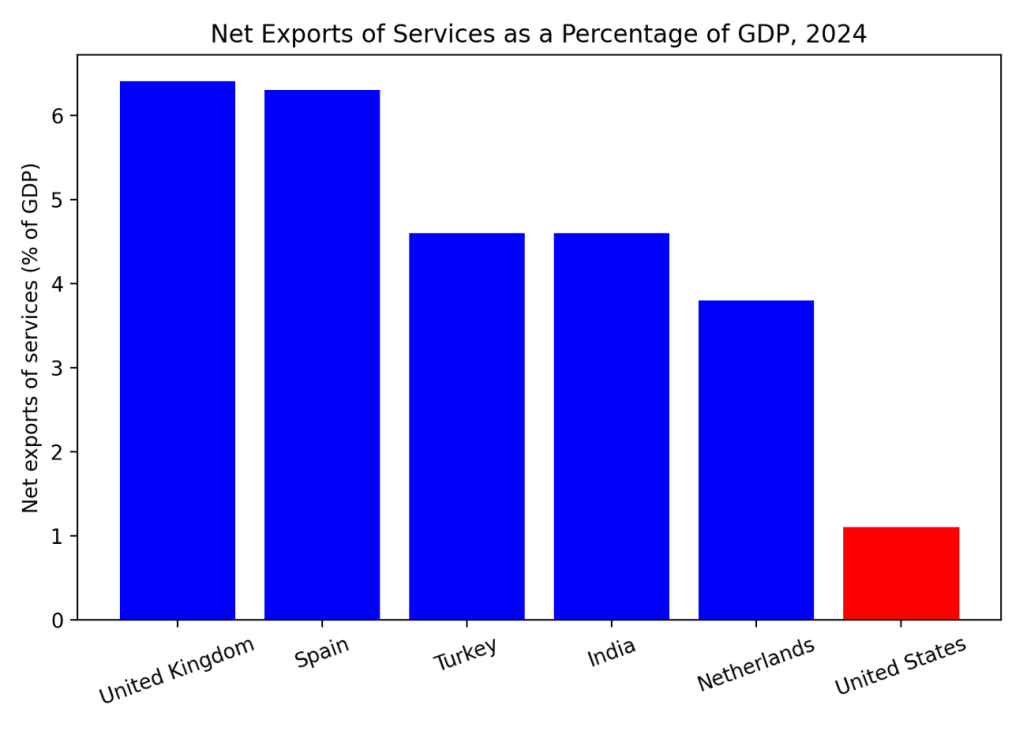

The following figure shows net exports in services as percentage of GDP among large economies. Measured this way, the largest net exporter of services is the United Kingdom, followed by Spain. The United States is included in graph (in red) for comparison and ranks ninth.

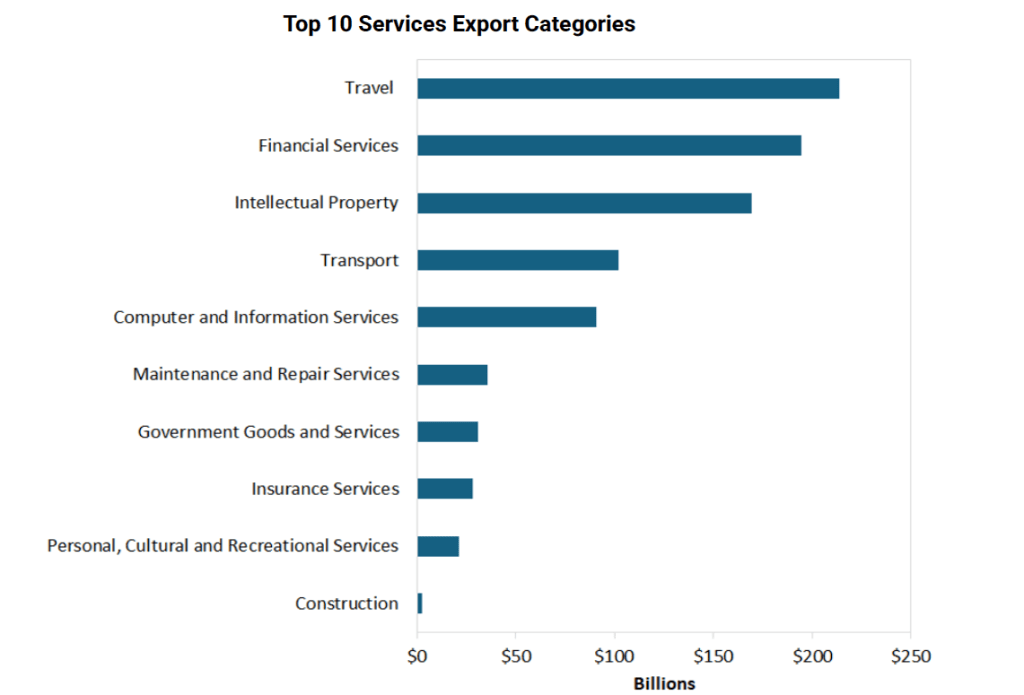

The following table from the St. Louis Fed’s blog posts shows the U.S. industries that export the most services.

The export of travel services represents largely foreign tourism in the United States. For example, if a family from France visits Walt Disney World in Florida, their spending would be included as an export of travel services.

Is the Price of a Thanksgiving Dinner Higher this Year? It Depends on What Side Dishes You Serve.

Image generated by ChatGPT

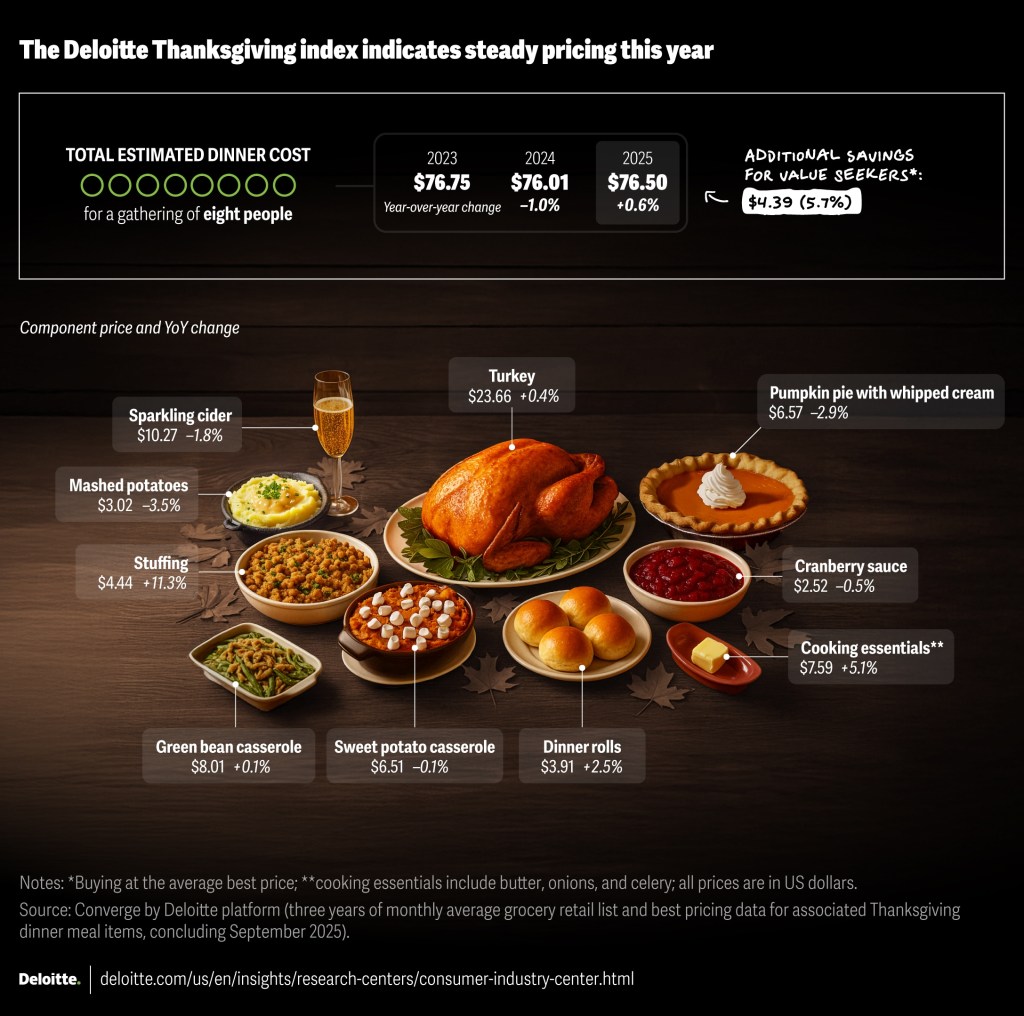

A perennial media story this time of year looks at whether a Thanksgiving turkey dinner costs more or less than last year. Not too surprisingly, the answer depends on what side dishes you serve with the turkey. Deloitte provides tax, consulting, and other services to businesses. Their calculation of the cost of a Thanksgiving dinner over the past three years can be found here.

The following image shows the food that they include in their cost calculation. For that particular Thanksgiving dinner, the cost is slightly higher than in 2024, although slightly lower than in 2023.

Image from deloitte.com

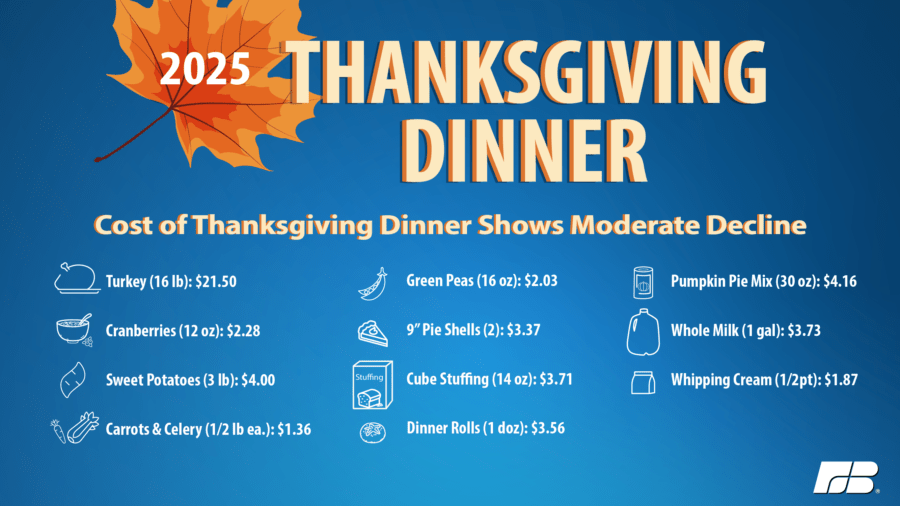

The following image from the American Farm Bureau Federation, a lobbying organization for U.S. farmers, shows the food they include in their calculation of the cost of a Thanksgiving dinner.

Image from fb.org

For a Thanksgiving dinner with those side dishes, the price is about 5 percent lower this year than last year.

Image from fb.org

Note that the two estimates differ in the cost of the turkey. It’s not clear whether the difference is due to the size of the turkey or to differences in the price of the turkey. Related point: The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) stopped collecting data on retail turkey prices in February 2020, at the start of the pandemic, and never resumed collecting them. Here’s the link to the BLS retail turkey price series on FRED. The series begins in January 1980 and ends in February 2020.

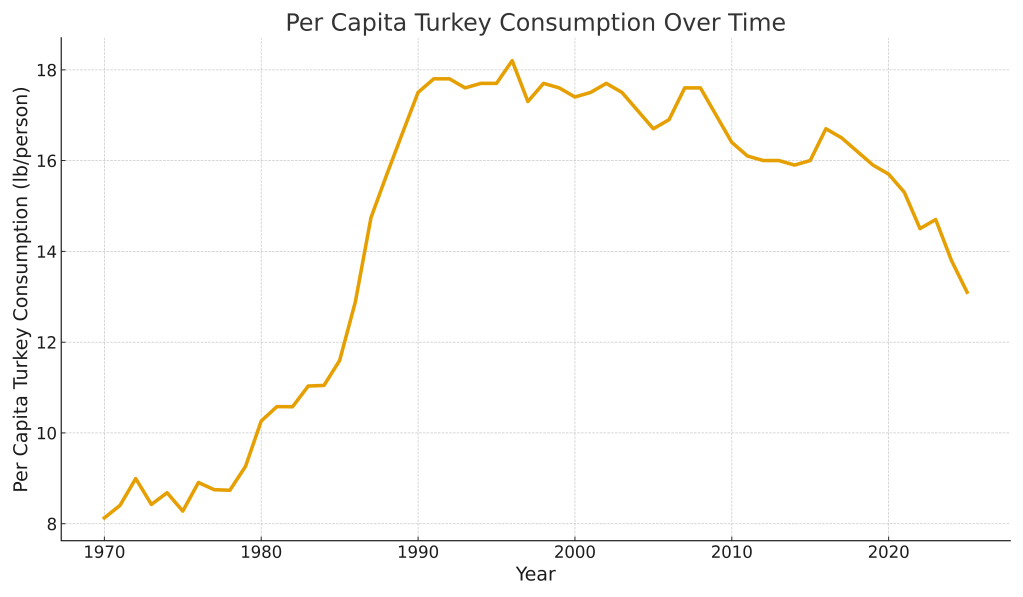

Justin Fox, in a column on bloomberg.com, notes that demand for turkey has been declining in recent years. The following figure uses data on turkey consumption per capita from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Turkey consumption peaked at 18.2 pounds per person in 1996 and has fallen to an estimated 13.1 pounds per person in 2025—a decline of about 28 percent. Is this decline an indication that people have moved away from eating turkey for Thanksgiving? Fox argues that it likely doesn’t. Note the rapid rise of turkey consumption between 1980 and 1990. Fox believes the surge in consumption was due to “both chicken and turkey [consumption increasing] as health concerns led many Americans to shun red meat starting in the late 1970s ….” In recent years, though, “red-meat consumption has steadied … chicken consumption has continued to rise, and turkey is losing out. Maybe people just don’t like how it tastes.” Glenn and Tony agree that, alas, turkey is often dry—although, admittedly, skilled cooks claim that it isn’t dry when prepared properly.

So, turkey may be holding its own at the heart of Thanksgiving dinners, but seems to be struggling to get on the menu during the rest of the year.

Is the iPhone Air Apple’s “New Coke”?

Image created by GPT

Most large firms selling consumer goods continually evaluate which new products they should introduce. Managers of these firms are aware that if they fail to fill a market niche, their competitors or a new firm may develop a product to fill the niche. Similarly, firms search for ways to improve their existing products.

For example, Ferrara Candy, had introduced Nerds in 1983. Although Nerds experienced steady sales over the following years, company managers decided to devote resources to improving the brand. In 2020, they introduced Nerds Gummy Clusters, which an article in the Wall Street Journal describes as being “crunchy outside and gummy inside.” Over five years, sales of Nerds increased from $50 millions to $500 million. Although the company’s market research “suggested that Nerds Gummy Clusters would be a dud … executives at Ferrara Candy went with their guts—and the product became a smash.”

Image of Nerds Gummy Clusters from nerdscandy.com

Firms differ on the extent to which they rely on market research—such as focus groups or polls of consumers—when introducing a new product or overhauling an existing product. Henry Ford became the richest man in the United States by introducing the Model T, the first low-priced and reliable mass-produced automobile. But Ford once remarked that if before introducing the Model T he had asked people the best way to improve transportation they would probably have told him to develop a faster horse. (Note that there’s a debate as to whether Ford ever actually made this observation.) Apple co-founder Steve Jobs took a similar view, once remaking in an interview that “it’s really hard to design products by focus groups. A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.” In another interview, Jobs stated: “We do no market research. We don’t hire consultants.”

Unsurprisingly, not all new products large firms introduce are successful—whether the products were developed as a result of market research or relied on the hunches of a company’s managers. To take two famous examples, consider the products shown in image at the beginning of this post—“New Coke” and the Ford Edsel.

Pepsi and Coke have been in an intense rivalry for decades. In the 1980s, Pepsi began to gain market share at Coke’s expense as a result of television commercials showcasing the “Pepsi Challenge.” The Pepsi Challenge had consumers choose from colas in two unlabeled cups. Consumers overwhelming chose the cup containing Pepsi. Coke’s management came to believe that Pepsi was winning the blind taste tests because Pepsi was sweeter than Coke and consumers tend to favor sweeter colas. In 1985, Coke’s managers decided to replace the existing Coke formula—which had been largely unchanged for almost 100 years—with New Coke, which had a sweeter taste. Unfortunately for Coke’s managers, consumers’ reaction to New Coke was strongly negative. Less than three months later, the company reintroduced the original Coke, now labeled “Coke Classic.” Although Coke produced both versions of the cola for a number of years, eventually they stopped selling New Coke.

Through the 1920s, the Ford Motor Company produced only two car models—the low-priced Model T and the high-priced Lincoln. That strategy left an opening for General Motors during the 1920s to introduce a variety of car models at a number of price levels. Ford scrambled during the 1930s and after the end of World War II in 1945 to add new models that would compete directly with some of GM’s models. After a major investment in new capacity and an elaborate marketing campaign, Ford introduced the Edsel in September 1957 to compete against GM’s mid-priced models: Pontiac, Oldsmobile, and Buick.

Unfortunately, the Edsel was introduced during a sharp, although relatively short, economic recession. As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 13 (Economics, Chapter 23), consumers typically cut back on purchases of consumer durables like automobiles during a recession. In addition, the Edsel suffered from reliability problems and many consumers disliked the unusual design, particularly of the front of the car. Consumers were also puzzled by the name Edsel. Ford CEO Henry Ford II was the grandson of Henry Ford and the son of Edsel Ford, who had died in 1943. Henry Ford II named in the car in honor of his father but the unusual name didn’t appeal to consumers. Ford ceased production of the car in November 1959 after losing $250 million, which was one of the largest losses in business history to that point. The name “Edsel” has lived on as a synonym for a disastrous product launch.

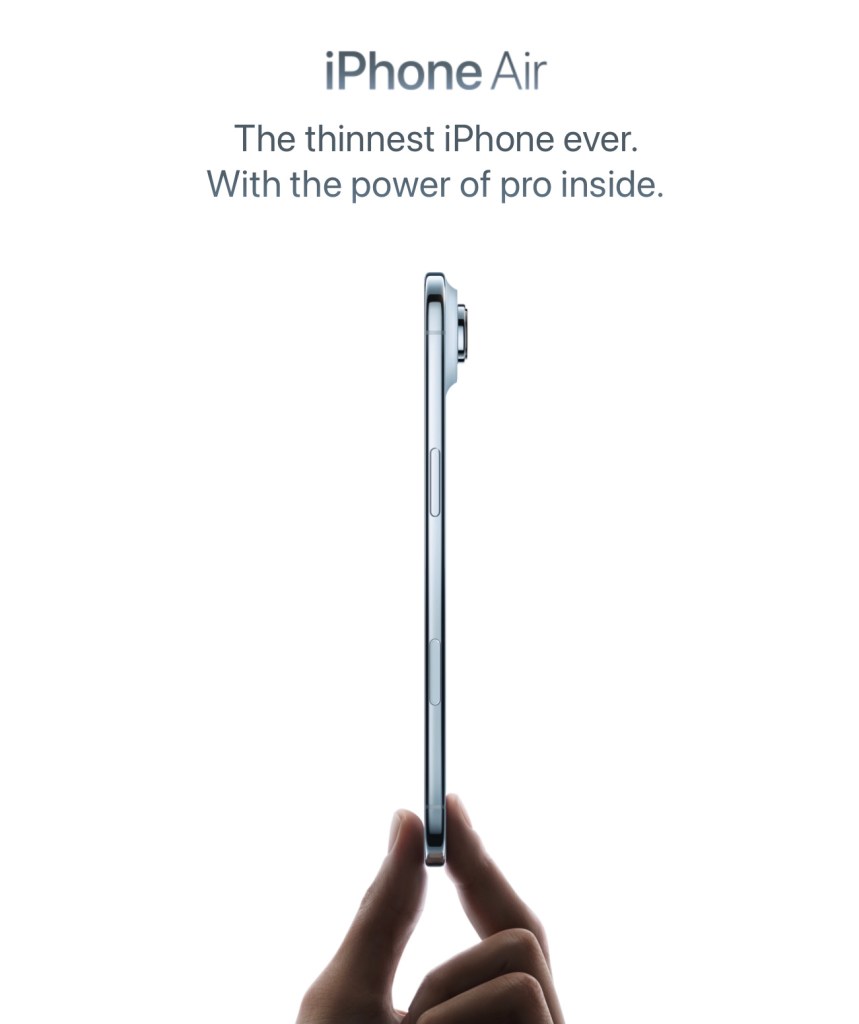

Image of iPhone Air from apple.com

Apple earns about half of its revenue and more than half of its profit from iPhone sales. Making sure that it is able to match or exceed the smartphone features offered by competitors is a top priority for CEO Tim Cook and other Apple managers. Because Apple’s iPhones are higher-priced than many other smartphones, Apple has tried various approaches to competing in the market for lower-priced smartphones.

In 2013, Apple was successful in introducing the iPad Air, a thinner, lower-priced version of its popular iPad. Apple introduced the iPhone Air in September 2025, hoping to duplicate the success of the iPad Air. The iPhone Air has a titanium frame and is lighter than the regular iPhone model. The Air is also thinner, which means that its camera, speaker, and its battery are all a step down from the regular iPhone 17 model. In addition, while the iPhone Air’s price is $100 lower than the iPhone 17 Pro, it’s $200 higher than the base model iPhone 17.

Unlike with the iPad Air, Apple doesn’t seem to have aimed the iPhone Air at consumers looking for a lower-priced alternative. Instead, Apple appears to have targeted consumers who value a thinner, lighter phone that appears more stylish, because of its titanium frame, and who are willing to sacrifice some camera and sound quality, as well as battery life. An article in the Wall Street Journal declared that: “The Air is the company’s most innovative smartphone design since the iPhone X in 2017.” As it has turned out, there are apparently fewer consumers who value this mix of features in a smartphone than Apple had expected.

Sales were sufficiently disappointing that within a month of its introduction, Apple ordered suppliers to cut back production of iPhone Air components by more than 80 percent. Apple was expected to produce 1 million fewer iPhone Airs during 2025 than the company had initially planned. An article in the Wall Street Journal labeled the iPhone Air “a marketing win and a sales flop.” According to a survey by the KeyBanc investment firm there was “virtually no demand for [the] iPhone Air.”

Was Apple having its New Coke moment? There seems little doubt that the iPhone Air has been a very disappointing new product launch. But its very slow sales haven’t inflicted nearly the damage that New Coke caused Coca-Cola or that the Edsel caused Ford. A particularly damaging aspect of New Coke was that was meant as a replacement for the existing Coke, which was being pulled from production. The result was a larger decline in sales than if New Coke had been offered for sale alongside the existing Coke. Similarly, Ford set up a whole new division of the company to produce and sell the Edsel. When Edsel production had to be stopped after only two years, the losses were much greater than they would have been if Edsel production hadn’t been planned to be such a large fraction of Ford’s total production of automobiles.

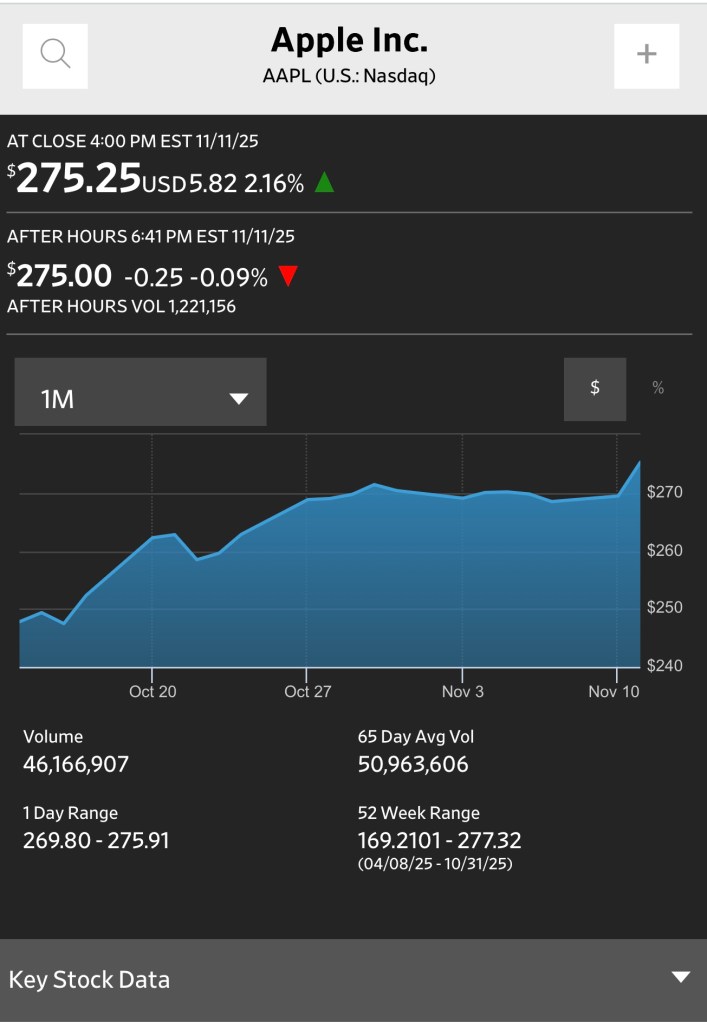

Although very slow iPhone Air sales have caused Apple to incur losses on the model, the Air was meant to be one of several iPhone models and not the only iPhone model. Clearly investors don’t believe that problems with the Air will matter much to Apple’s profits in the long run. The following graphic from the Wall Street Journal shows that Apple’s stock price has kept rising even after news of serious problems with Air sales became public in late October.

So, while the iPhone Air will likely go down as a failed product launch, it won’t achieve the legendary status of New Coke or the Edsel.

Solved Problem: Using the Demand and Supply Model to Analyze the Effects of a Tariff on Televisions

Supports: Microeconomics, Macroeconomics, Economics, and Essentials of Economics, Chapter 4, Section 4.4

Image generated by ChapGPT

The model of demand and supply is useful in analyzing the effects of tariffs. In Chapter 9, Section 9.4 (Macroeconomics, Chapter 7, Section 7.4) we analyze the situation—for instance, the market for sugar—when U.S. demand is a small fraction of total world demand and when the U.S. both produces the good and imports it.

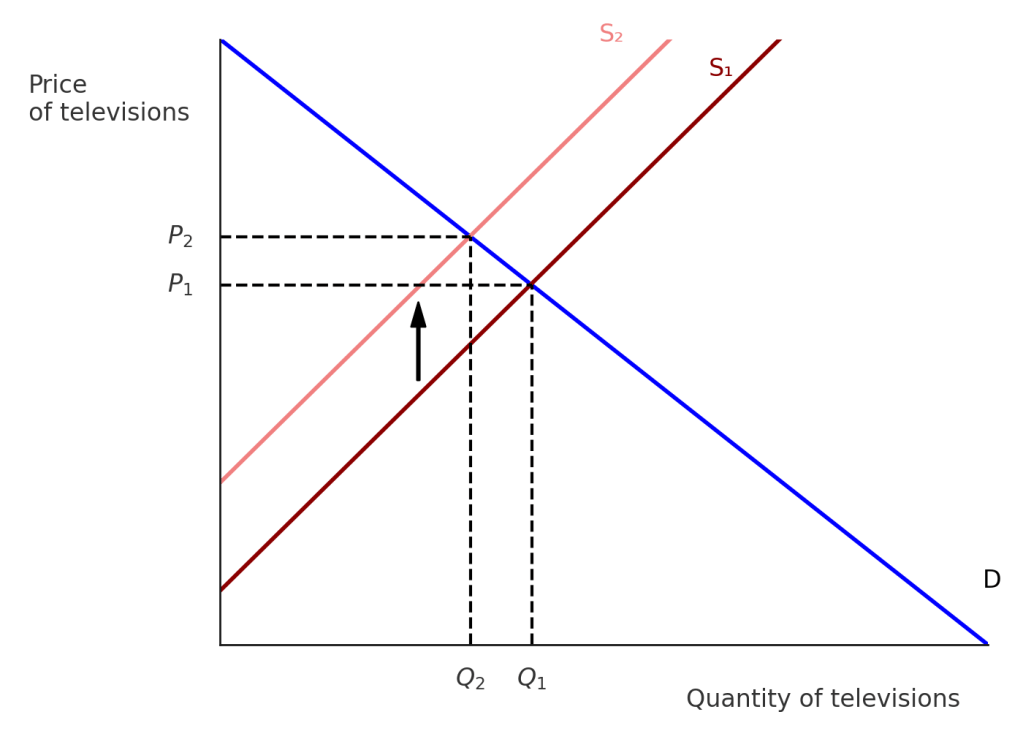

In this problem, we look at the television market and assume that no domestic firms make televisions. (A few U.S. firms assemble limited numbers of televisions from imported components.) As a result, the supply of televisions consists entirely of imports. Beginning in April, the Trump administration increased tariff rates on imports of televisions from Japan, South Korea, China, and other countries. Tariffs are effectively a tax on imports, so we can use the analysis in Chapter 4, Section 4.4, “The Economic Effect of Taxes” to analyze the effect of tariffs on the market for televisions.

- Use a demand and supply graph to illustrate the effect of an increased tariff on imported televisions on the market for televisions in the United States. Be sure that your graph shows any shifts of the curves and the equilibrium price and quantity of televisions before and after the tariff increase.

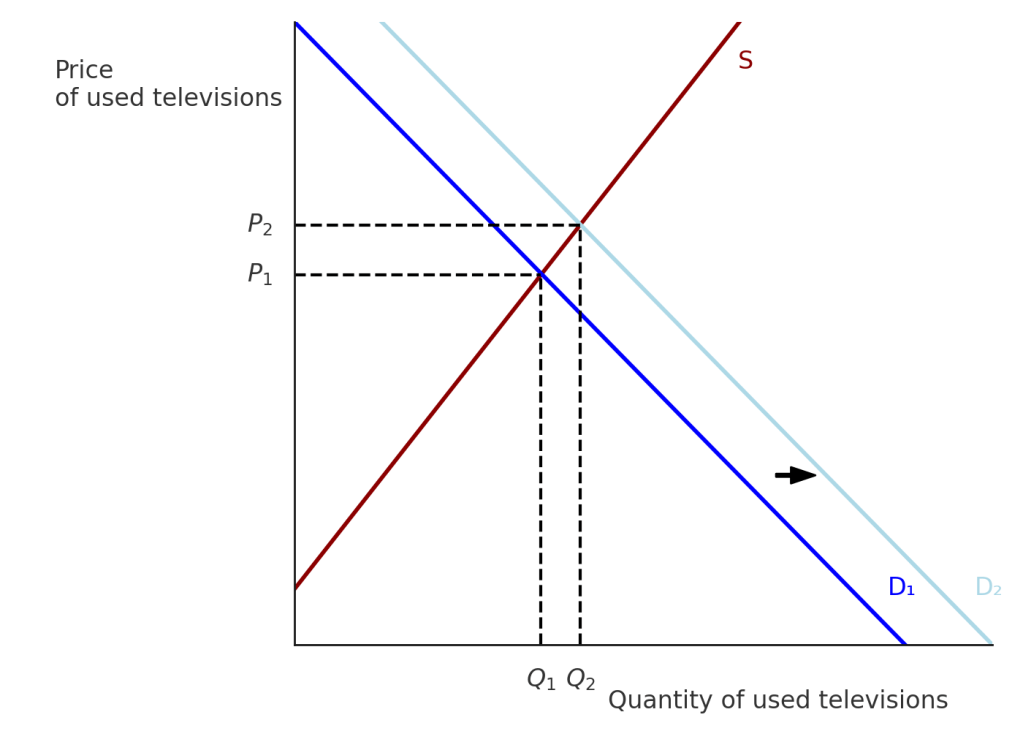

- An article in the Wall Street Journal discussed the effect of tariffs on the market for used goods. Use a second demand and supply graph to show the effect of a tariff on imports of new televisions on the market in the United States for used televisions. Assume that no used televisions are imported and that the supply curve for used televisions is upward sloping.

Solving the Problem

Step 1: Review the chapter material. This problem is about the effect of a tariff on an imported good on the domestic market for the good. Because a tariff is a like a tax, you may want to review Chapter 4, Section 4.4, “The Economic Effect of Taxes.”

Step 2: Answer part a. by drawing a demand and supply graph of the market for televisions in the United States that illustrates the effect of an increased tariff on imported televisions. The following figure shows that a tariff causes the supply curve of televisions to shift up from S1 to S2. As a result, the equilibrium price increases from P1 to P2, while the equilibrium quantity falls from Q1 to Q2.

Step 2: Answer part b. by drawing a demand and supply graph of the market for used televisions in the United States that illustrates the effect on that market of an increased tariff on imports of new televisions. Although the tariff on imported televisions doesn’t directly affect the market for used televisions, it does so indirectly. As the article from the Wall Street Journal notes, “Today, in the tariff era, demand for used goods is surging.” Because used televisions are substitutes for new televisions, we would expect that an increase in the price of new televisions would cause the demand curve for used televisions to shift to the right, as shown in the following figure. The result will be that the equilibrium price of used televisions will increase from P1 to P2, while the equilibrium quantity of used televisions will increase from Q1 to Q2.

To summarize: A tariff on imports of new televisions increases the price of both new and used televisions. It decreases the quantity of new televisions sold but increases the quantity of used televisions sold.

NEW! 11-07-25- Podcast – Authors Glenn Hubbard & Tony O’Brien discuss Tariffs, AI, and the Economy

Glenn Hubbard and Tony O’Brien begin by examining the challenges facing the Federal Reserve due to incomplete economic data, a result of federal agency shutdowns. Despite limited information, they note that growth remains steady but inflation is above target, creating a conundrum for policymakers. The discussion turns to the upcoming appointment of a new Fed chair and the broader questions of central bank independence and the evolving role of monetary policy. They also address the uncertainty surrounding AI-driven layoffs, referencing contrasting academic views on whether artificial intelligence will complement existing jobs or lead to significant displacement. Both agree that the full impact of AI on productivity and employment will take time to materialize, drawing parallels to the slow adoption of the internet in the 1990s.

The podcast further explores the recent volatility in stock prices of AI-related firms, comparing the current environment to the dot-com bubble and questioning the sustainability of high valuations. Hubbard and O’Brien discuss the effects of tariffs, noting that price increases have been less dramatic than expected due to factors like inventory buffers and contractual delays. They highlight the tension between tariffs as tools for protection and revenue, and the broader implications for manufacturing, agriculture, and consumer prices. The episode concludes with reflections on the importance of ongoing observation and analysis as these economic trends evolve.

Pearson Economics · Hubbard OBrien Economics Podcast – 11-06-25 – Economy, AI, & Tariffs