Authors Glenn Hubbard and Tony O’Brien as they talk about the leading economic issue of early 2022 – inflation! They discuss the resurgence of inflation to levels not seen in 40 years due to a combination of miscalculations in monetary and fiscal policy. The role of Quantitative Easing (QE) – and its future – is discussed in depth. Listen today to gain insights into the economic landscape.

Category: Macroeconomics

President Biden Makes Three Nominations to the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors

The terms of the seven members of the Fed’s Board of Governors are staggered with a new 14-year term beginning each February 1 of even-numbered years. That system of appointments was intended to limit turnover on the board with the aim of avoiding sudden swings in monetary policy. But because in practice board members often resign before their terms have expired and because presidents sometimes delay making appointments to empty positions, presidents sometimes face the need to make multiple appointments at the same time. In January 2022, President Joe Biden nominated the following three people—one lawyer and two economists—to positions on the board:

- Sarah Bloom Raskin is the Colin W. Brown Distinguished Professor of the Practice of Law at Duke University. She served on the Board of Governors from 2010 to 2014 before resigning to become deputy secretary of the Treasury, a position she held until 2017. If confirmed by the Senate, she would serve as the board’s vice chair for supervision, becoming the second person to hold that position, which was established by the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act. The vice chair for supervision has important responsibility in leading the Fed’s regulation and supervision of banks.

- Philip Jefferson is the Paul B. Freeland Professor of Economics, vice president for academic affairs, and dean of the faculty at Davidson College. He received his PhD from the University of Virginia in 1990. He previously taught at Swarthmore College and served a year as an economist at the Board of Governors.

- Lisa Cook is a professor of economics at Michigan State University. She received her PhD in economics from the University of California, Berkeley in 1997. She served on the Council of Economic Advisers from 2011 to 2012 during the Obama Administration.

Before taking their positions, the three nominees must first be confirmed by the U.S. Senate. At this point, it’s unclear whether any of the three nominees will encounter significant opposition to their confirmation. Senator Pat Toomey of Pennsylvania has raised some concerns about Raskin’s nomination, arguing that she:

“has specifically called for the Fed to pressure banks to choke off credit to traditional energy companies and to exclude those employers from any Fed emergency lending facilities. I have serious concerns that she would abuse the Fed’s narrow statutory mandates on monetary policy and banking supervision to have the central bank actively engaged in capital allocation.”

If confirmed, the nominees will join these other four board members:

- Jerome Powell has been nominated by President Biden to a second term as Fed Chair that, if the Senate votes favorably on the nomination, would begin in February 2022. Powell was first nominated to the board by President Obama in 2011 and nominated by President Trump to his first term as chair, which began in February 2018.

- Lael Brainard was first nominated to the board by President Obama in 2014. President Biden has nominated Brainard to serve as vice-chair of the board. If confirmed, she would succeed in that position Richard Clarida who resigned in January 2022.

- Christopher Waller was nominated by President Trump to a term on the board in 2020. He had previously served as director of research at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. He received his PhD in economics from Washington State University and served as a professor of economics at Notre Dame University and the University of Kentucky. His term expires in 2030.

- Michelle Bowman was nominated by President Trump to a term on the board in 2018. Bowman had served as the state bank commissioner of Kansas and as an executive at a local bank in Kansas. She has a law degree from Washburn University. She was reappointed to a full 14-year term in 2020.

Sources: Senator Toomey’s statement on Sarah Bloom Raskin’s nomination can be found here. An overview of the membership of the Board of Governors can be found here on the Federal Reserve’s website. An Associated Press article covering President Biden’s nominations can be found here.

Macroeconomics or Microeconomics? Is a Lack of Competition in Some Industries Behind the Increase in Inflation?

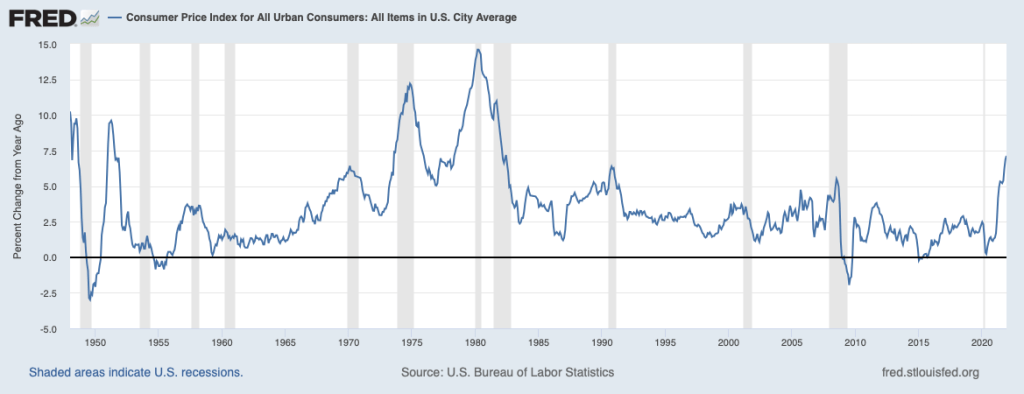

In January 2022, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) announced that inflation, measured as the percentage change in the consumer price index (CPI) from December 2020 to December 2021, was 7 percent. That was the highest rate since June 1982, which was near the end of the Great Inflation that lasted from 1968 to 1982. The following figure shows the inflation rate since the beginning of 1948.

What explains the surge in inflation? Most economists believe that it is the result of the interaction of increases in aggregate demand resulting from very expansionary monetary and fiscal policy and disruptions to supply in some industries as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. (We discuss movements in aggregate demand and aggregate supply during the pandemic in the updated editions of Economics, Chapter 23, Section 23.3 and Macroeconomics, Chapter 13, Section, 13.3.)

But President Joe Biden has suggested that mergers and acquisitions in some industries—he singled out meatpacking—have reduced competition and contributed to recent price increases. Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren has made a broader claim about reduced competition being responsible for the surge in inflation: “Market concentration has allowed giant corporations to hide behind claims of increased costs to fatten their profit margins. [Corporations] are raising prices because they can.” And “Corporations are exploiting the pandemic to gouge consumers with higher prices on everyday essentials, from milk to gasoline.”

Do many economists agree that reduced competition explains inflation? The Booth School of Business at the University of Chicago periodically surveys a panel of more than 40 well-known academic economists for their opinions on significant policy issues. Recently, the panel was asked whether they agreed with these statements:

- A significant factor behind today’s higher US inflation is dominant corporations in uncompetitive markets taking advantage of their market power to raise prices in order to increase their profit margins.

- Antitrust interventions could successfully reduce US inflation over the next 12 months.

- Price controls as deployed in the 1970s could successfully reduce US inflation over the next 12 months.

Large majorities of the panel disagreed with statements 1. and 2.—that is, they don’t believe that a lack of competition explains the surge in inflation or that antitrust actions by the federal government would be likely to reduce inflation in the coming year. A smaller majority disagreed with statement 3., although even some of those who agreed that price controls would reduce inflation stated that they believed price controls were an undesirable policy. For instance, while he agreed with statement 3., Oliver Hart of Harvard noted that: “They could reduce inflation but the consequence would be shortages and rationing.”

One way to characterize the panel’s responses is that they agreed that the recent inflation was primarily a macroeconomic issue—involving movements in aggregate demand and aggregate supply—rather than a microeconomic issue—involving the extent of concentration in individual industries.

The panels responses can be found here.

Sources for Biden and Warren quotes: Greg Ip, “Is Inflation a Microeconomic Problem? That’s What Biden’s Competition Push Is Betting,” Wall Street Journal, January 12, 2022; and Patrick Thomas and Catherine Lucey, “Biden Promotes Plan Aimed at Tackling Meat Prices,” Wall Street Journal, January 3, 2022; and https://twitter.com/SenWarren/status/1464353269610954759?s=20

Lawrence Summers Remains Pessimistic about Inflation

Lawrence Summers, professor of economics at Harvard University and secretary of the Treasury under President Bill Clinton, has been outspoken in arguing that monetary and fiscal have been too expansionary. In February 2021, just before Congress passed the American Rescure Plan, which increased federal government spending by $1.9 trillion, Summers cautioned that “there is a chance that macroeconomic stimulus on a scale closer to World War II levels than normal recession levels will set off inflationary pressures of a kind we have not seen in a generation, with consequences for the value of the dollar and financial stability.”

In a brief CNN interview found at this LINK, Summers indicates that he remains concerned that inflation may persist at high levels for a longer period than many other economists, including policymakers at the Federal Reserve, believe.

Source for quote: Lawrence H. Summers, “The Biden Stimulus Is Admirably Ambitious. But It Brings Some Big Risks, Too,” Washington Post, February 4, 2021.

Glenn’s Article from the Atlantic: “Even My Business-School Students Have Doubts About Capitalism”

Link to the article on the Atlantic’s site.

During a lecture in my Modern Political Economy class this fall, I explained—as I have to many students over the course of four decades in academia—that capitalism’s adaptation to globalization and technological change had produced gains for all of society. I went on to say that capitalism has been an engine of wealth creation and that corporations seeking to maximize their long-term shareholder value had made the whole economy more efficient. But several students in the crowded classroom pushed back. “Capitalism leaves many people and communities behind,” one student said. “Adam Smith’s invisible hand seems invisible because it’s not there,” declared another.

I know what you’re thinking: For undergraduates to express such ideas is hardly news. But these were M.B.A. students in a class that I teach at Columbia Business School. For me, those reactions took some getting used to. Over the years, most of my students have eagerly embraced the creative destruction that capitalism inevitably brings. Innovation and openness to new technologies and global markets have brought new goods and services, new firms, new wealth—and a lot of prosperity on average. Many master’s students come to Columbia after working in tech, finance, and other exemplars of American capitalism. If past statistics are any guide, most of our M.B.A. students will end up back in the business world in leadership roles.

The more I thought about it, the more I could see where my students were coming from. Their formative years were shaped by the turbulence after 9/11, the global financial crisis, the Great Recession, and years of debate about the unevenness of capitalism’s benefits across individuals. They are now witnessing a pandemic that caused mass unemployment and a breakdown in global supply chains. Corporate recruiters are trying to win over hesitant students by talking up their company’s “mission” or “purpose”—such as bringing people together or meeting one of society’s big needs. But these gauzy assertions that companies care about more than their own bottom line are not easing students’ discontent.

Over the past four decades, many economists—certainly including me—have championed capitalism’s openness to change, stressed the importance of economic efficiency, and urged the government to regulate the private sector with a light touch. This economic vision has yielded gains in corporate efficiency and profitability and lifted average American incomes as well. That’s why American presidents from Ronald Reagan to Barack Obama have mostly embraced it.

Yet even they have made exceptions. Early in George W. Bush’s presidency, when I chaired his Council of Economic Advisers, he summoned me and other advisers to discuss whether the federal government should place tariffs on steel imports. My recommendation against tariffs was a no-brainer for an economist. I reminded the president of the value of openness and trade; the tariffs would hurt the economy as a whole. But I lost the argument. My wife had previously joked that individuals fall into two groups—economists and real people. Real people are in charge. Bush proudly defined himself as a real person. This was the political point that he understood: Disruptive forces of technological change and globalization have left many individuals and some entire geographical areas adrift.

In the years since, the political consequences of that disruption have become all the more striking—in the form of disaffection, populism, and calls to protect individuals and industries from change. Both President Donald Trump and President Joe Biden have moved away from what had been mainstream economists’ preferred approach to trade, budget deficits, and other issues.

Economic ideas do not arise in a vacuum; they are influenced by the times in which they are conceived. The “let it rip” model, in which the private sector has the leeway to advance disruptive change, whatever the consequences, drew strong support from such economists as Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman, whose influential writings showed a deep antipathy to big government, which had grown enormously during World War II and the ensuing decades. Hayek and Friedman were deep thinkers and Nobel laureates who believed that a government large enough for top-down economic direction can and inevitably will limit individual liberty. Instead, they and their intellectual allies argued, government should step back and accommodate the dynamism of global markets and advancing technologies.

But that does not require society to ignore the trouble that befalls individuals as the economy changes around them. In 1776, Adam Smith, the prophet of classical liberalism, famously praised open competition in his book The Wealth of Nations. But there was more to Smith’s economic and moral thinking. An earlier treatise, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, called for “mutual sympathy”—what we today would describe as empathy. A modern version of Smith’s ideas would suggest that government should play a specific role in a capitalist society—a role centered on boosting America’s productive potential(by building and maintaining broad infrastructure to support an open economy) and on advancing opportunity (by pushing not just competition but also the ability of individual citizens and communities to compete as change occurs).

The U.S. government’s failure to play such a role is one thing some M.B.A. students cite when I press them on their misgivings about capitalism. Promoting higher average incomes alone isn’t enough. A lack of “mutual sympathy” for people whose career and community have been disrupted undermines social support for economic openness, innovation, and even the capitalist economic system itself.

The United States need not look back as far as Smith for models of what to do. Visionary leaders have taken action at major economic turning points; Abraham Lincoln’s land-grant colleges and Franklin Roosevelt’s G.I. Bill, for example, both had salutary economic and political effects. The global financial crisis and the coronavirus pandemic alike deepen the need for the U.S. government to play a more constructive role in the modern economy. In my experience, business leaders do not necessarily oppose government efforts to give individual Americans more skills and opportunities. But business groups generally are wary of expanding government too far—and of the higher tax levels that doing so would likely produce.

My students’ concern is that business leaders, like many economists, are too removed from the lives of people and communities affected by forces of change and companies’ actions. That executives would focus on general business and economic concerns is neither surprising nor bad. But some business leaders come across as proverbial “anywheres”—geographically mobile economic actors untethered to actual people and places—rather than “somewheres,” who are rooted in real communities.

This charge is not completely fair. But it raises concerns that broad social support for business may not be as firm as it once was. That is a problem if you believe, as I do, in the centrality of businesses in delivering innovation and prosperity in a capitalist system. Business leaders wanting to secure society’s continuing support for enterprise don’t need to walk away from Hayek’s and Friedman’s recounting of the benefits of openness, competition, and markets. But they do need to remember more of what Adam Smith said.

As my Columbia economics colleague Edmund Phelps, another Nobel laureate, has emphasized, the goal of the economic system Smith described is not just higher incomes on average, but mass flourishing. Raising the economy’s potential should be a much higher priority for business leaders and the organizations that represent them. The Business Roundtable and the Chamber of Commerce should strongly support federally funded basic research that shifts the scientific and technological frontier and applied-research centers that spread the benefits of those advances throughout the economy. Land-grant colleges do just that, as do agricultural-extension services and defense-research applications. Promoting more such initiatives is good for business—and will generate public support for business. After World War II, American business groups understood that the Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe would benefit the United States diplomatically and commercially. They should similarly champion high-impact investment at home now.

To address individual opportunity, companies could work with local educational institutions and commit their own funds for job-training initiatives. But the U.S. as a whole should do more to help people compete in the changing economy—by offering block grants to community colleges, creating individualized reemployment accounts to support reentry into work, and enhancing support for lower-wage, entry-level work more generally through an expanded version of the earned-income tax credit. These proposals are not cheap, but they are much less costly and more tightly focused on helping individuals adapt than the social-spending increases being championed in Biden’s Build Back Better legislation are. The steps I’m describing could be financed by a modestly higher corporate tax rate if necessary.

My M.B.A. students who doubt the benefits of capitalism see the various ways in which government policy has ensured the system’s survival. For instance, limits on monopoly power have preserved competition, they argue, and government spending during economic crises has forestalled greater catastrophe.

They also see that something is missing. These young people, who have grown up amid considerable pessimism, are looking for evidence that the system can do more than generate prosperity in the aggregate. They need proof that it can work without leaving people and communities to their fate. Businesses will—I hope—keep pushing for greater globalization and promoting openness to technological change. But if they want even M.B.A. students to go along, they’ll also need to embrace a much bolder agenda that maximizes opportunities for everyone in the economy.

Link to the Amazon listing of Glenn’s new book.

How Do We Know When the Economy Is at Maximum Employment?

According to the Federal Reserve Act, the Fed must conduct monetary policy “so as to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.” Neither “maximum employment” nor “stable prices” are defined in the act.

The Fed has interpreted “stable prices” to mean a low rate of inflation. Since 2012, the Fed has had an explicit inflation target of 2 percent. When the Fed announced its new monetary policy strategy in August 2020, it modified its inflation target by stating that it would attempt to achieve an average inflation rate of 2 percent over time. As Fed Chair Jerome Powell stated: “Our approach can be described as a flexible form of average inflation targeting.” (Note that although the consumer price index (CPI) is the focus of many media stories on inflation, the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation is changes in the core personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index. The PCE is a broader measure of the price level than is the CPI because it includes the prices of all the goods and services included in consumption category of GDP. “Core” means that the index excludes food and energy prices. For a further discussion see, Economics, Chapter 25, Section 15.5 and Macroeconomics, Chapter 15, Section 15.5.)

There is more ambiguity about how to determine whether the economy is at maximum employment. For many years, a majority of members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) focused on the natural rate of unemployment (also called the non-accelerating rate of unemployment (NAIRU)) as the best gauge of when the U.S. economy had attained maximum employment. The lesson many economists and policymakers had taken from the experience of the Great Inflation that lasted from the late 1960s to the early 1980s was if the unemployment rate was persistently below the natural rate of unemployment, inflation would begin to accelerate. Because monetary policy affects the economy with a lag, many policymakers believed it was important for the Fed to react before inflation begins to significantly increase and a higher inflation rate becomes embedded in the economy.

At least until the end of 2018, speeches and other statements by some members of the FOMC indicated that they continued to believe that the Fed should pay close attention to the relationship between the natural rate of unemployment and the actual rate of unemployment. But by that time some members of the FOMC had concluded that their decision to begin raising the target for the federal funds rate in December 2015 and continuing raising it through December 2018 may have been a mistake because their forecasts of the natural rate of unemployment may have been too high. For instance, Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic noted in a speech that: “If estimates of the NAIRU are actually too conservative, as many would argue they have been … unemployment could have averaged one to two percentage points lower” than it actually did.

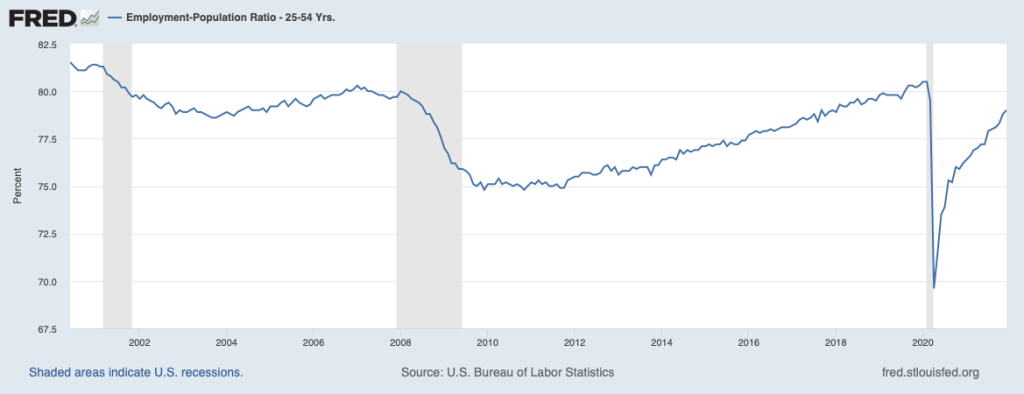

Accordingly, when the Fed announced its new monetary policy strategy in August 2020, it indicated that it would consider a wider range of data—such as the employment-population ratio—when determining whether the labor market had reached maximum employment. At the time, Fed Chair Powell noted that: “the maximum level of employment is not directly measurable and [it] changes over time for reasons unrelated to monetary policy. The significant shifts in estimates of the natural rate of unemployment over the past decade reinforce this point.”

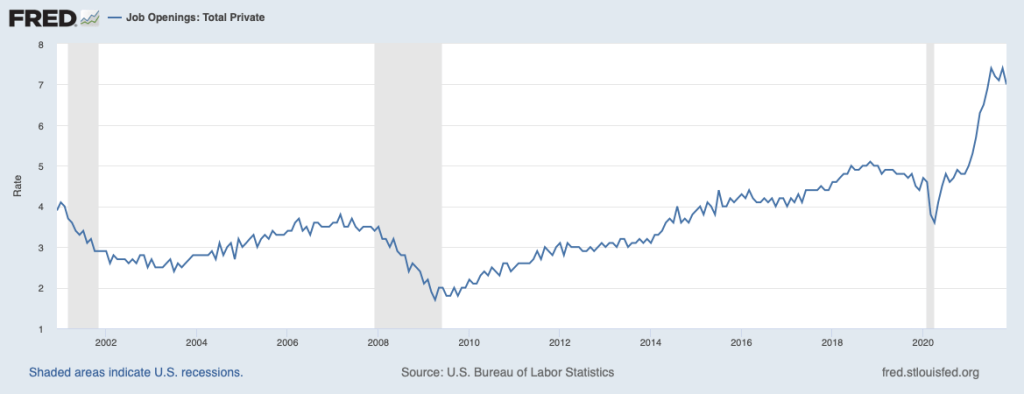

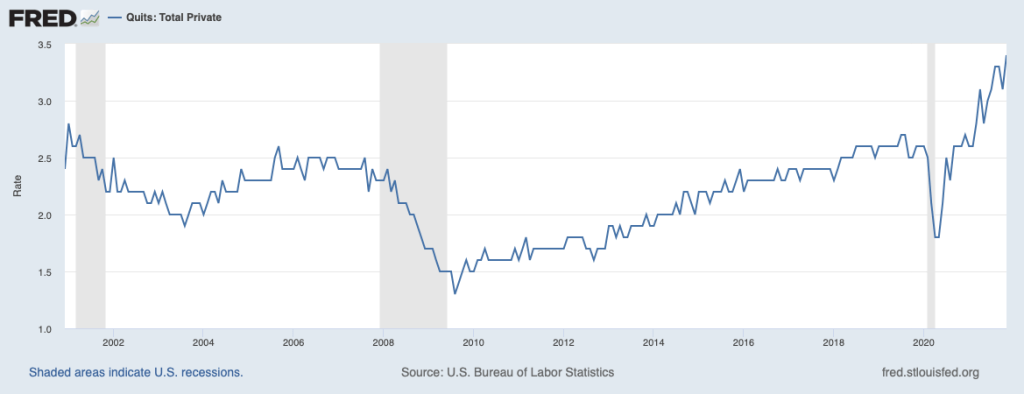

As the economy recovered from the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Fed faced particular difficulty in assessing the state of the labor market. Some labor market indicators appeared to show that the economy was close to maximum employment while other indicators showed that the labor market recovery was not complete. For instance, in December 2021, the unemployment rate was 3.9 percent, slightly below the average of the FOMC members estimates of the natural rate of unemployment, which was 4.0 percent. Similarly, as the first figure below shows, job vacancy rates were very high at the end of 2021. (The BLS calculates job vacancy rates, also called job opening rates, by dividing the number of unfilled job openings by the sum of total employment plus job openings.) As the second figure below shows, job quit rates were also unusually high, indicating that workers saw the job market as being tight enough that if they quit their current job they could find easily another job. (The BLS calculates job quit rates by dividing the number of people quitting jobs by total employment.) By those measures, the labor market seemed close to maximum employment.

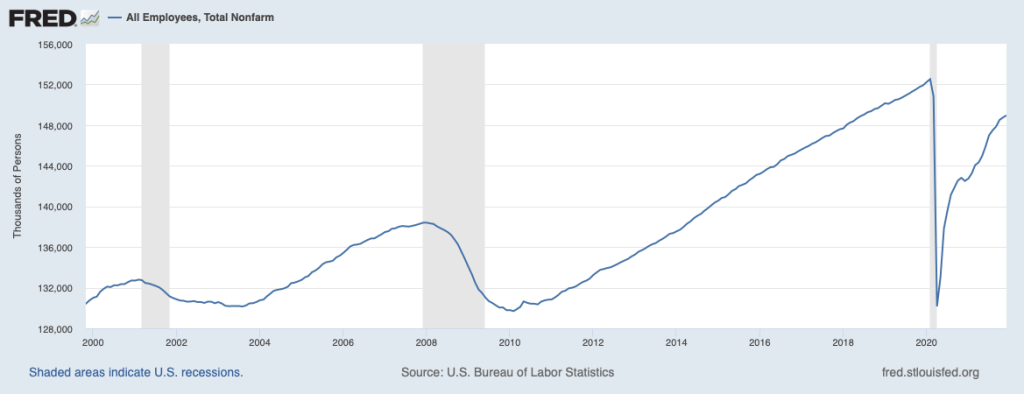

But as the first figure below shows, total employment in December 2021 was still 3.5 million below its level of early 2020, just before the U.S. economy began to experience the effects of the pandemic. Some of the decline in employment can be accounted for by older workers retiring, but as the second figure below indicates, employment of prime-age workers (those between the ages of 25 and 54), had not recovered to pre-pandemic levels.

How to reconcile these conflicting labor market indicators? In January 2022, Fed Chair Powell testified before the Senate Banking Committee as the Senate considered his nomination for a second four-year term as chair. In discussing the state of the economy he offered the opinion that: “We’re very rapidly approaching or at maximum employment.” He noted that inflation as measured by changes in the CPI had been running above 5 percent since June 2021: “If these high levels of inflation get entrenched in our economy, and in people’s thinking, then inevitably that will lead to much tighter monetary policy from us, and it could lead to a recession.” In that sense, “high inflation is a severe threat to the achievement of maximum employment.”

At the time of Powell’s testimony, the FOMC had already announced that it was moving to a less expansionary monetary policy by reducing its purchases of Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities and by increasing its target for the federal funds rate in the near future. He argued that these actions would help the Fed achieve its dual mandate by reducing the inflation rate, thereby heading off the need for larger increases in the federal funds rate that might trigger a recession. Avoiding a recession would help achieve the goal of maximum employment.

Powell’s remarks did not make explicit which labor market indicators the Fed would focus on in determining whether the goal of maximum employment had been obtained. It did make clear that the Fed’s new policy of average inflation targeting did not mean that the Fed would accept inflation rates as high as those of the second half of 2021 without raising its target for the federal funds rate. In that sense, the Fed’s monetary policy of 2022 seemed consistent with its decades-long commitment to heading off increases in inflation before they lead to a significant increase in the inflation rate expected by households, businesses, and investors.

Note: For a discussion of the background to Fed policy, see Economics, Chapter 25, Section 25.5 and Chapter 27, Section 17.4, and Macroeconomics, Chapter 15, Section 15.5 and Chapter 17, Section 17.4.

Sources: Jeanna Smialek, “Jerome Powell Says the Fed is Prepared to Raise Rates to Tame Inflation,” New York Times, January 11, 2022; Nick Timiraos, “Fed’s Powell Says Economy No Longer Needs Aggressive Stimulus,” Wall Street Journal, January 11, 2022; and Federal Open Market Committee, “Meeting Calendars, Statements, and Minutes,” federalreserve.gov, January 5, 2022.

New Information on Fed Policy Affects Stock and Bond Prices

Most economists believe that monetary policy actions, such as changes in the Fed’s pace of buying bonds or in its target for the federal funds rate, affect real GDP and employment only with a lag of several months or longer. But monetary policy actions can have a more immediate effect on the prices of financial assets like stocks and bonds.

Investors in financial markets are forward looking because the prices of financial assets are determined by investors’ expectations of the future. (We discuss this point in Economics and Microeconomics, Chapter 8, Section 8.2, Macroeconomics, Chapter 6, Section 6.2, and Money, Banking and the Financial System, Chapter 6.) For instance, stock prices depend on the future profitability of firms, so if investors come to believe that future economic growth is likely to be slower, thereby reducing firms’ profits, the investors will sell stocks causing stock prices to decline.

Similarly, holders of existing bonds will suffer losses if the interest rates on newly issued bonds are higher than the interest rates on existing bonds. Therefore, if investors come to believe that future interest rates are likely to be higher than they had previously expected them to be, they will sell bonds, thereby causing their prices to decline and the interest rates on them to rise. (Recall that the prices of bonds and the interest rates (or yields) on them move in opposite directions: If the price of a bond falls, the interest rate on the bond will increase; if the price of a bond rises, the interest rate on the bond will decrease. To review this concept, see the Appendix to Economics and Microeconomics Chapter 8, the Appendix to Macroeconomics Chapter 6, and Money, Banking, and the Financial System, Chapter 3.)

Because monetary policy actions can affect future interest rates and future levels of real GDP, investors are alert for any new information that would throw light on the Fed’s intentions. When new information appears, the result can be a rapid change in the prices of financial assets. We saw this outcome on January 5, 2022, when the Fed released the minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee meeting held on December 14 and 15, 2021. At the conclusion of the meeting, the FOMC announced that it would be reducing its purchases of long-term Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities. These purchases are intended to aid the expansion of real GDP and employment by keeping long-term interest rates from rising. The FOMC also announced that it intended to increase its target for the federal funds rate when “labor market conditions have reached levels consistent with the Committee’s assessments of maximum employment.”

When the minutes of this FOMC meeting were released at 2 pm on January 5, 2022, many investors realized that the Fed might increase its target for the federal funds rate in March 2022—earlier than most had expected. In this sense, the release of the FOMC minutes represented new information about future Fed policy and the markets quickly reacted. Selling of stocks caused the S&P 500 to decline by nearly 100 points (or about 2 percent) and the Nasdaq to decline by more than 500 points (or more than 3 percent). Similarly, the price of Treasury securities fell and, therefore, their interest rates rose.

Investors had concluded from the FOMC minutes that economic growth was likely to be slower during 2022 and interest rates were likely to be higher than they had previously expected. This change in investors’ expectations was quickly reflected in falling prices of stocks and bonds.

Sources: An Associated Press article on the reaction to the release of the FOMC minutes can be found HERE; the FOMC’s statement following its December 2021 meeting can be found HERE; and the minutes of the FOMC meeting can be found HERE.

President Biden Decides to Reappoint Jerome Powell as Fed Chair

When Congress established the Federal Reserve System in 1913, it intended to make the Fed independent of the rest of the federal government. (We discuss this point in the opener to Macroeconomics, Chapter 15 and to Economics, Chapter 25. We discuss the structure of the Federal Reserve System in Macroeconomics, Chapter 14, Section 14.4 and in Economics, Chapter 24, Section 24.4.) The ultimate responsibility for operating the Fed lies with the Board of Governors in Washington, DC. Members of the Board of Governors are nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate to 14-year nonrenewable terms. Congress intentionally made the terms of Board members longer than the eight years that a president serves (if the president is reelected to a second term).

The president is still able to influence the Board of Governors in two ways:

- The terms of members of the Board of Governors are staggered so that one term expires on January 31 of each even-number year. Although this approach means that it’s unlikely that a president will be able to appoint all seven members during the president’s time in office, in practice, many members do not serve their full 14-year terms. So, a president who serves two terms will typically have an opportunity to appoint more than four members of the Board.

- The president nominates one member of the Board to serve a renewable four-year term as chair, subject to confirmation by the Senate.

The terms of Fed chairs end in the year after the year a president begins either the president’s first or second term. As a result, presidents are often faced with what is at times a difficult decision as to whether to reappoint a Fed chair who was first appointed by a president of the other party.

For example, after taking office in January 2009, President Barack Obama, a Democrat, faced the decision of whether to nominate Fed Chair Ben Bernanke to a second term to begin in 2010. Bernanke had originally been appointed by President George W. Bush, a Republican. Partly because the economy was still suffering the aftereffects of the financial crisis and the Great Recession, President Obama decided that it would potentially be disruptive to financial markets to replace Bernanke, so he nominated him for a second term.

After taking office in January 2017, President Donald Trump, a Republican, had to decide whether to nominate Fed Chair Janet Yellen, who had been appointed by Obama, to another term that would begin in 2018. He decided not to reappoint Yellen and instead nominated Jerome Powell, who was already serving on the Board of Governors. Although a Republican, Powell had been appointed to the Board in 2014 by Obama.

President Biden’s reasons for nominating Powell to a second term to begin in 2022 were similar to Obama’s reasons for nominating Bernanke to a second term: The U.S. economy was still recovering from the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, including the strains the pandemic had inflicted on the financial system. He believed that replacing Powell with another nominee would have been potentially disruptive to the financial system.

There had been speculation that Biden would choose Lael Brainard, who has served on the Board of Governors since 2014 following her appointment by Obama, to succeed Powell as Fed chair. Instead, Biden appointed Brainard as vice chair of the Board. In announcing the appointments, Biden stated: “America needs steady, independent, and effective leadership at the Federal Reserve. That’s why I will nominate Jerome Powell for a second term as Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and Dr. Lael Brainard to serve as Vice Chair of the Board of Governors.”

Sources: Nick Timiraos and Andrew Restuccia, “Biden Will Tap Jerome Powell for New Term as Fed Chairman,” wsj.com, November 22, 2021; and Jeff Cox and Thomas Franck, “Biden Picks Jerome Powell to Lead the Fed for a Second Term as the U.S. Battles Covid and Inflation,” cnbc.com, November 22, 2021.

The U.S. Dollar in the World Economy

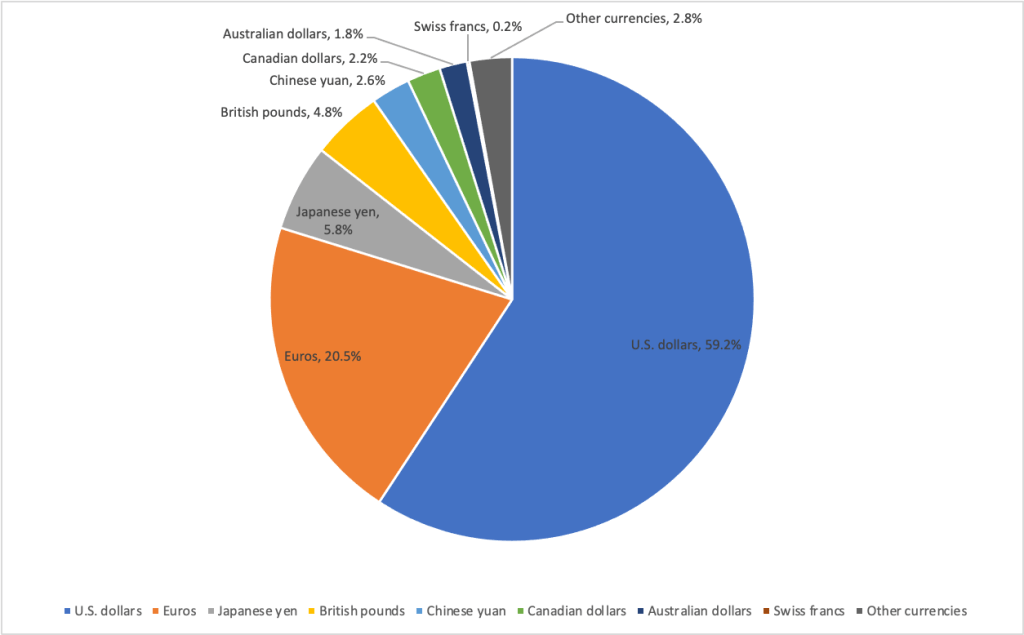

The U.S. dollar is the most important currency in the world economy. The funds that governments and central banks hold to carry out international transactions are called their official foreign exchange reserves. (See Macroeconomics, Chapter 18, Section 18.1 and Economics, Chapter 28, Section 28.1.) There are 180 national currencies in the world and foreign exchange reserves can be held in any of them. In practice, international transactions are conducted in only a few currencies. Because the U.S. dollar is used most frequently in international transactions, the majority of foreign exchange reserves are held in U.S. dollars. The following figure shows the composition of official foreign exchange reserves by currency as of mid-2021.

Over time, the percentage of foreign exchange reserves in U.S. dollars has been gradually declining, although the dollar seems likely to remain the dominant foreign reserve currency for a considerable period. Does the United States gain an advantage from being the most important foreign reserve currency? Economists and policymakers are divided in their views. At the most basic level, dollars are claims on U.S. goods and services and U.S. financial assets. When foreign governments, banks, corporations, and investors hold U.S. dollars rather than spending them, they are, in effect, providing the United States with interest-free loans. U.S. households and firms also benefit from often being able to use U.S. currency around the world when buying and selling goods and services and when borrowing, rather than first having to exchange dollars for other currencies.

But there are also disadvantages to the dollar being the dominant reserve currency. Because the dollar plays this role, the demand for the dollar is higher than it would otherwise be, which increases the exchange rate between the dollar and other currencies. If the dollar lost its status as the key foreign reserve currency, the exchange rate might decline by as much as 30 percent. A decline in the value of the dollar by that much would substantially increase exports of U.S. goods. Barry Eichengreen of the University of California, Berkeley, has noted that the result might be “a shift in the composition of what America exports from Treasury [bonds and other financial securities] … toward John Deere earthmoving equipment, Boeing Dreamliners, and—who knows—maybe even motor vehicles and parts.”

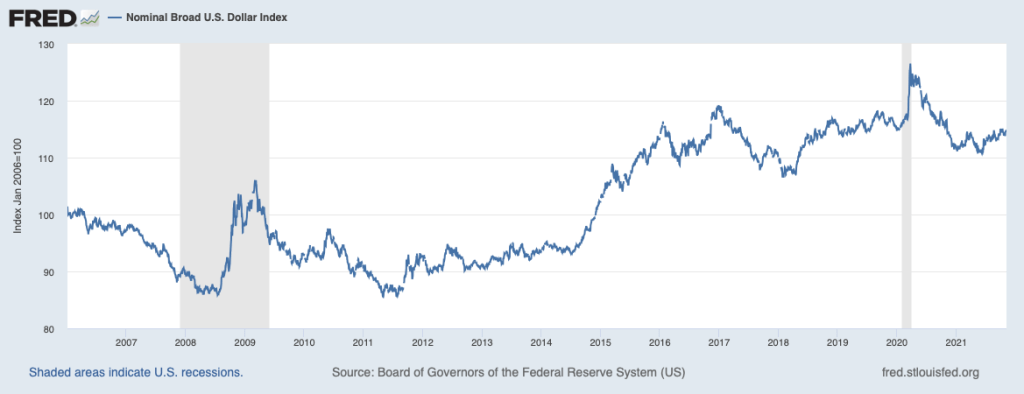

As shown in the following figure, the importance of the U.S. dollar in the world economy is also indicated by the sharp increase in the demand for dollars and, therefore, in the exchange rate during the financial crisis in the fall of 2008 and during the spread of Covid-19 in the spring of 2020. (The exchange rate in the figure is a weighted average of the exchange rates between the dollar and the currencies of the major trading partners of the United States.) As an article in the Economist put it: “Last March, when suddenly the priority was to have cash, the cash that people wanted was dollars.”

Sources: International Monetary Fund, “Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves,” data.imf.org; Alina Iancu, Neil Meads, Martin Mühleisen, and Yiqun Wu, “Glaciers of Global Finance: The Currency Composition of Central Banks’ Reserve Holdings,” blogs.imf.org, December 16, 2020; Barry Eichengreen, Exorbitant Privilege: The Rise and Fall of the Dollar and the Future of the International Monetary System, New York: Oxford University Press, 2001, p. 173; “How America’s Blockbuster Stimulus Affects the Dollar,” economist.com, March 13, 2021; and Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

The Case of the Missing Highways

In November 2021, Congress passed and President Joe Biden signed the trillion dollar Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, often referred to as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill (BIF). The bill included funds for:

- Highways and bridges

- Buses, subways, and other mass transit systems

- Amtrak, the federally sponsored corporation that provides most intercity railroad service in the United States, to modernize and expand its service

- A network of charging stations for electric cars

- Maintenance and modernization of ports and airports

- Securing infrastructure against cyberattacks and climate change

- Increasing access to clean drinking water

- Expansion of broadband internet, particularly in rural areas

- Treating soil and groundwater pollution

As with other infrastructure bills, although the federal government provides funding, much of the actual work—and some of the funding—is the responsibility of state and local governments. For instance, nearly all highway construction in the United States is carried out by state highway or transportation departments. These state government agencies design new highways and bridges and contract primarily with private construction firms to do the work.

Because state and local governments carry out most highway and bridge construction, Congress doesn’t always achieve the results they intended when providing the funding. Bill Dupor, an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, has discovered a striking example of this outcome. In 2009, in response to the Great Recession of 2007–2009, Congress passed and President Barack Obama signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). (We discuss the ARRA in Macroeconomics, Chapter 16, Section 16.5 and Economics, Chapter 26, Section 26.5.) Included in the act was $27.5 billion in new spending on highways. This amount represented a 76 percent increase on previous levels of federal spending on highways. As Dupor puts it, Congress and the president had “great hopes for the potential of these new grants to create and save construction jobs as well as improve highways.”

Surprisingly, though, Dupor’s analysis of data on the condition of bridges, on miles of highways constructed, and on the number of workers employed in highway construction shows that the billions of dollars Congress directed to infrastructure spending under ARRA had little effect on the nation’s highways and bridges and did not increase employment on highway construction.

What happened to the $27.5 billion Congress had appropriated? Dupor concludes that after receiving the federal funds most state governments:”cut their own contributions to highway capital spending which, in turn, … [freed] up those funds for other uses. Since states were facing budget stress from declining tax revenues resulting from the recession, it stands to reason that states had the incentive to do so.”

He finds that following passage of ARRA many states cut their spending on highway infrastructure while at the same time increasing their spending on other things. For instance, Maryland cut its spending on highways by $73 per person while increasing its spending on education by $129 per person.

Can we conclude that that Congressional infrastructure spending under ARRA was a failure and the funds were wasted? To answer this question, first keep in mind that when it authorizes an increase in infrastructure spending, Congress often has two goals in mind:

- To maintain and expand the country’s infrastructure

- To engage in countercyclical fiscal policy

The first goal is obvious but the second can be important as well. Typically, Congress is most likely to authorize a large increase in infrastructure spending during a recession. When the ARRA was passed in the spring of 2009, Congress and President Obama were clear that they hoped that the increased spending authorized in the bill would reduce unemployment from the very high levels at that time. (Economists and policymakers debated whether additional countercyclical fiscal policy was needed at the time Congress passed the BIF in late 2021. Although the Biden administration argued that the spending was needed to increase employment, some economists argued that the BIF did little to deal with the supply problems then plaguing the economy.)

We discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 16, Section 16.2 (Economics, Chapter 26, Section 26.2), how expansionary fiscal policy can increase real GDP and employment during a recession. If Dupor’s analysis is correct, Congress failed to achieve its first goal of improving the country’s infrastructure. But Dupor’s findings that states, in effect, used the federal infrastructure funds for other types of spending, such as on education, means that Congress did meet its second goal. That conclusion holds if in the absence of receiving the $27.5 billion in funds from ARRA, state governments would have had to cut their spending elsewhere, which would have reduced overall government expenditures and reduced aggregate demand.

As this discussion indicates, the details of how fiscal policy affects the economy can be complex.

Sources: Gabriel T. Rubin and Eliza Collins, “What’s in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill? From Amtrak to Roads to Water Systems,” wsj.com, November 6, 2021; Bill Dupor, “So Why Didn’t the 2009 Recovery Act Improve the Nation’s Highways and Bridges?” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, Vol. 99, No. 2, Second Quarter 2017, pp. 169-182; Greg Ip, “President Biden’s Economic Agenda Wasn’t Designed for Shortages and Inflation,” wsj.com, November 10, 2021; and Executive Office of the President, “Updated Fact Sheet: Bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act,” whitehouse.gov, August 2, 2021.