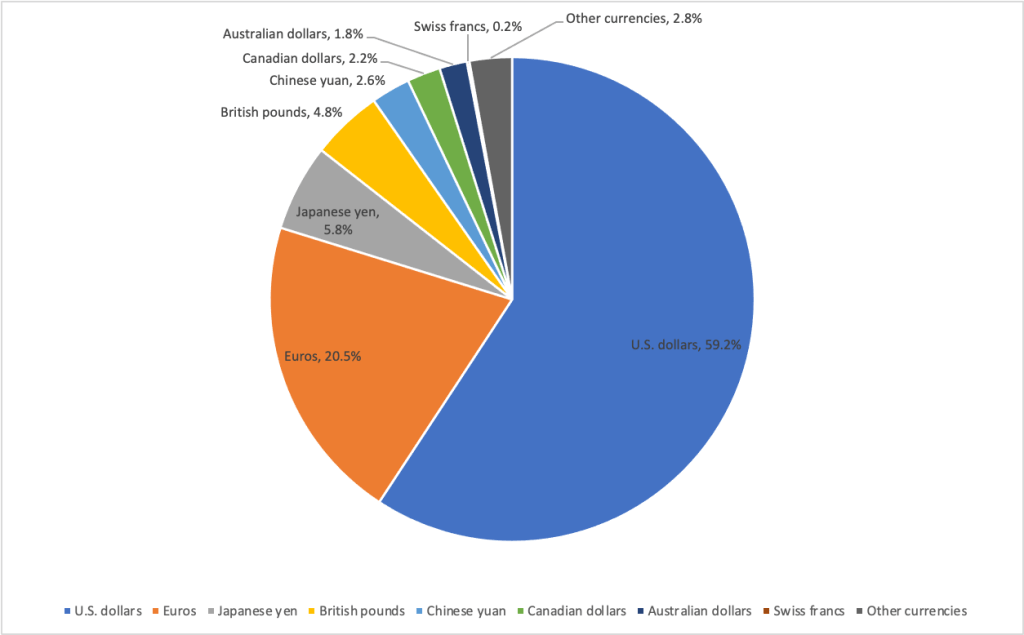

The U.S. dollar is the most important currency in the world economy. The funds that governments and central banks hold to carry out international transactions are called their official foreign exchange reserves. (See Macroeconomics, Chapter 18, Section 18.1 and Economics, Chapter 28, Section 28.1.) There are 180 national currencies in the world and foreign exchange reserves can be held in any of them. In practice, international transactions are conducted in only a few currencies. Because the U.S. dollar is used most frequently in international transactions, the majority of foreign exchange reserves are held in U.S. dollars. The following figure shows the composition of official foreign exchange reserves by currency as of mid-2021.

Over time, the percentage of foreign exchange reserves in U.S. dollars has been gradually declining, although the dollar seems likely to remain the dominant foreign reserve currency for a considerable period. Does the United States gain an advantage from being the most important foreign reserve currency? Economists and policymakers are divided in their views. At the most basic level, dollars are claims on U.S. goods and services and U.S. financial assets. When foreign governments, banks, corporations, and investors hold U.S. dollars rather than spending them, they are, in effect, providing the United States with interest-free loans. U.S. households and firms also benefit from often being able to use U.S. currency around the world when buying and selling goods and services and when borrowing, rather than first having to exchange dollars for other currencies.

But there are also disadvantages to the dollar being the dominant reserve currency. Because the dollar plays this role, the demand for the dollar is higher than it would otherwise be, which increases the exchange rate between the dollar and other currencies. If the dollar lost its status as the key foreign reserve currency, the exchange rate might decline by as much as 30 percent. A decline in the value of the dollar by that much would substantially increase exports of U.S. goods. Barry Eichengreen of the University of California, Berkeley, has noted that the result might be “a shift in the composition of what America exports from Treasury [bonds and other financial securities] … toward John Deere earthmoving equipment, Boeing Dreamliners, and—who knows—maybe even motor vehicles and parts.”

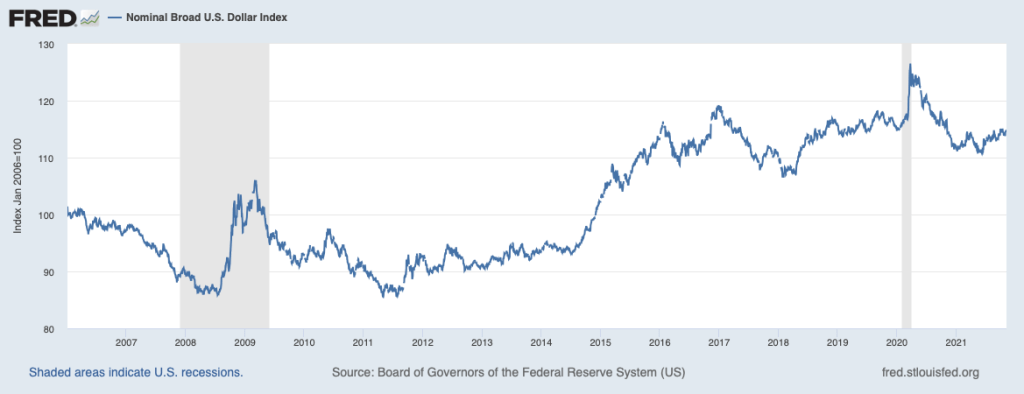

As shown in the following figure, the importance of the U.S. dollar in the world economy is also indicated by the sharp increase in the demand for dollars and, therefore, in the exchange rate during the financial crisis in the fall of 2008 and during the spread of Covid-19 in the spring of 2020. (The exchange rate in the figure is a weighted average of the exchange rates between the dollar and the currencies of the major trading partners of the United States.) As an article in the Economist put it: “Last March, when suddenly the priority was to have cash, the cash that people wanted was dollars.”

Sources: International Monetary Fund, “Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves,” data.imf.org; Alina Iancu, Neil Meads, Martin Mühleisen, and Yiqun Wu, “Glaciers of Global Finance: The Currency Composition of Central Banks’ Reserve Holdings,” blogs.imf.org, December 16, 2020; Barry Eichengreen, Exorbitant Privilege: The Rise and Fall of the Dollar and the Future of the International Monetary System, New York: Oxford University Press, 2001, p. 173; “How America’s Blockbuster Stimulus Affects the Dollar,” economist.com, March 13, 2021; and Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.