A bookstore in New York City closed during Covid. (Photo from the New York Times)

Four years ago, in mid-March 2020, Covid–19 began to significantly affect the U.S. economy, with hospitalizations rising and many state and local governments closing schools and some businesses. In this blog post we review what’s happened to key macro variables during the past four years. Each monthly series starts in February 2020 and the quarterly series start in the fourth quarter of 2019.

Production

Real GDP declined by 5.8 percent from the fourth quarter of 2019 to the first quarter of 2020 and by an additional 28.0 percent from the first quarter of 2020 to the second quarter. This decline was by far the largest in such a short period in the history of the United States. From the second quarter to the third quarter of 2020, as businesses began to reopen, real GDP increased by 34.8 percent, which was by far the largest increase in a single quarter in U.S. history.

Industrial production followed a similar—although less dramatic—path to real GDP, declining by 16.8 percent from February 2020 to April 2020 before increasing by 12.3 percent from April 2020 to June 2020. Industrial production did not regain its February 2020 level until March 2022. The swings in industrial production were smaller than the swings in GDP because industrial production doesn’t include the output of the service sector, which includes firms like restaurants, movie theaters, and gyms that were largely shutdown in some areas. (Industrial production measures the real output of the U.S. manufacturing, mining, and electric and gas utilities industries. The data are issued by the Federal Reserve and discussed here.)

Employment

Nonfarm payroll employment, collected by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) in its establishment survey, followed a path very similar to the path of production. Between February and April 2020, employment declined by an astouding 22 million workers, or by 14.4 percent. This decline was by far the largest in U.S. history over such a short period. Employment increased rapidly beginning in April but didn’t regain its February 2020 level until June 2022.

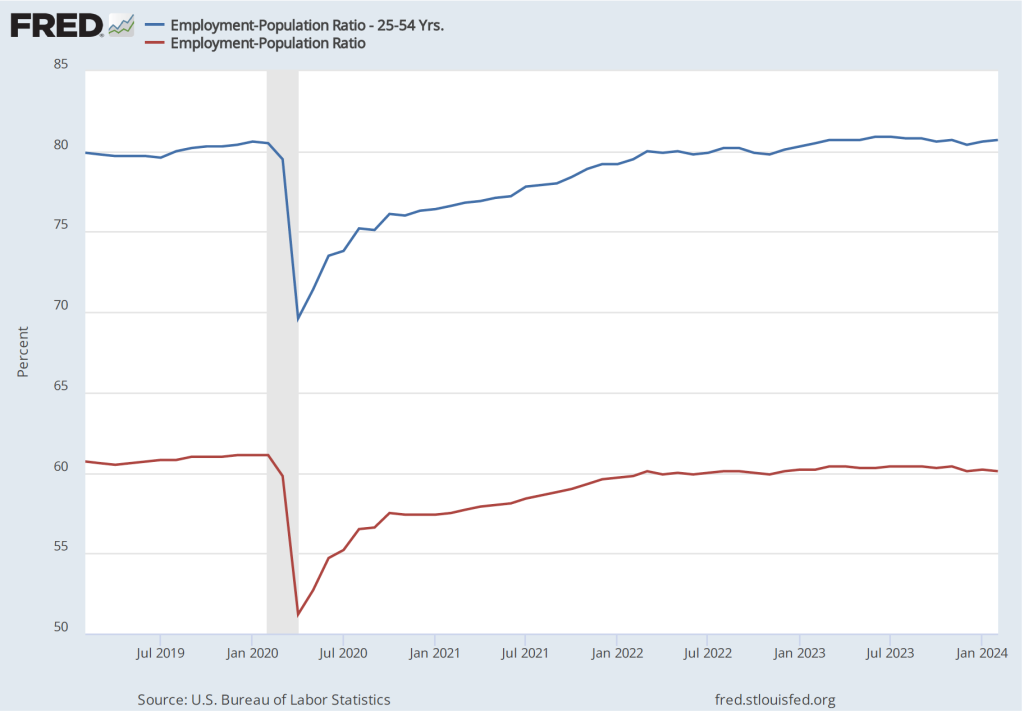

The employment-population ratio measures the percentage of the working-age population that is employed. It provides a more comprehensive measure of an economy’s utilization of available labor than does the total number of people employed. In the following figure, the blue line shows the employment-population ratio for the whole working-age population and the red line shows the employment-population ratio for “prime age workers,” those aged 25 to 54.

For both groups, the employment-population ratio plunged as a result of Covid and then slowly recovered as the production began increasing after April 2020. The employment-population ratio for prime age workers didn’t regain its February 2020 value until February 2023, an indication of how long it took the labor market to fully overcome the effects of the pandemic. As of February 2024, the employment-population ratio for all people of working age hasn’t returned to its February 2020 value, largely because of the aging of the U.S. population.

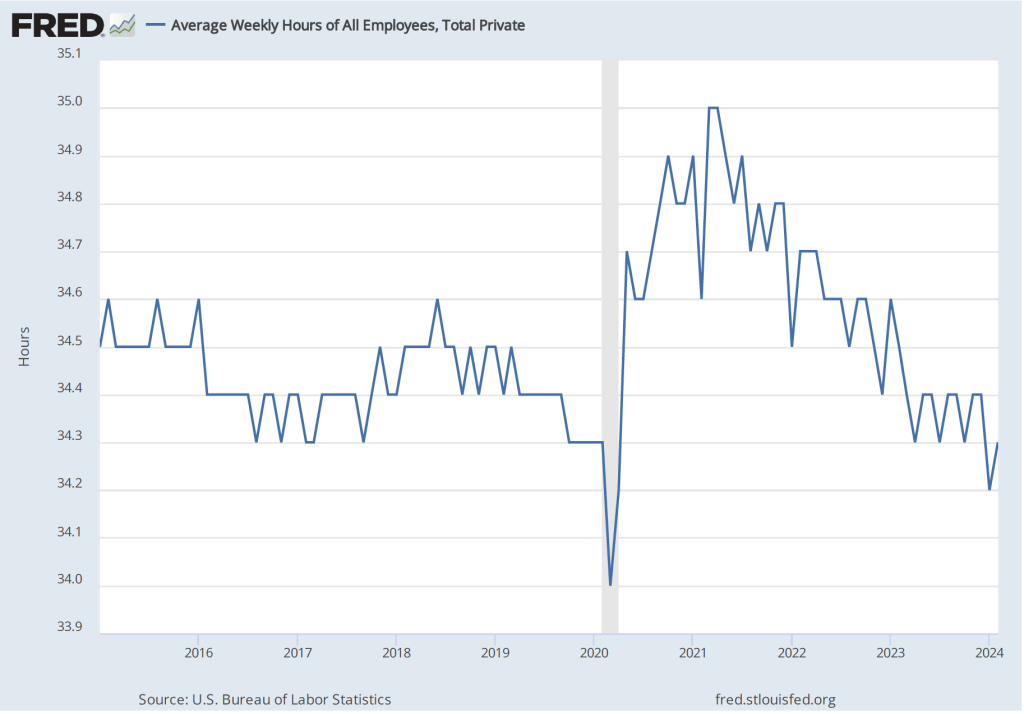

Average weekly hours worked followed an unusual pattern, declining during March 2020 but then increasing to beyond its February 2020 level to a peak in April 2021. This increase reflects firms attempting to deal with a shortage of workers by increasing the hours of those people they were able to hire. By April 2023, average weekly hours worked had returned to its February 2020 level.

Income

Real average hourly earnings surged by more than six percent between February and April 2020—a very large increase over a two-month period. But some of the increase represented a composition effect—as workers with lower incomes in services industries such as restaurants were more likely to be out of work during this period—rather than an actual increase in the real wages received by people employed during both months. (Real average hourly earnings are calculated by dividing nominal average hourly earnings by the consumer price index (CPI) and multiplying by 100.)

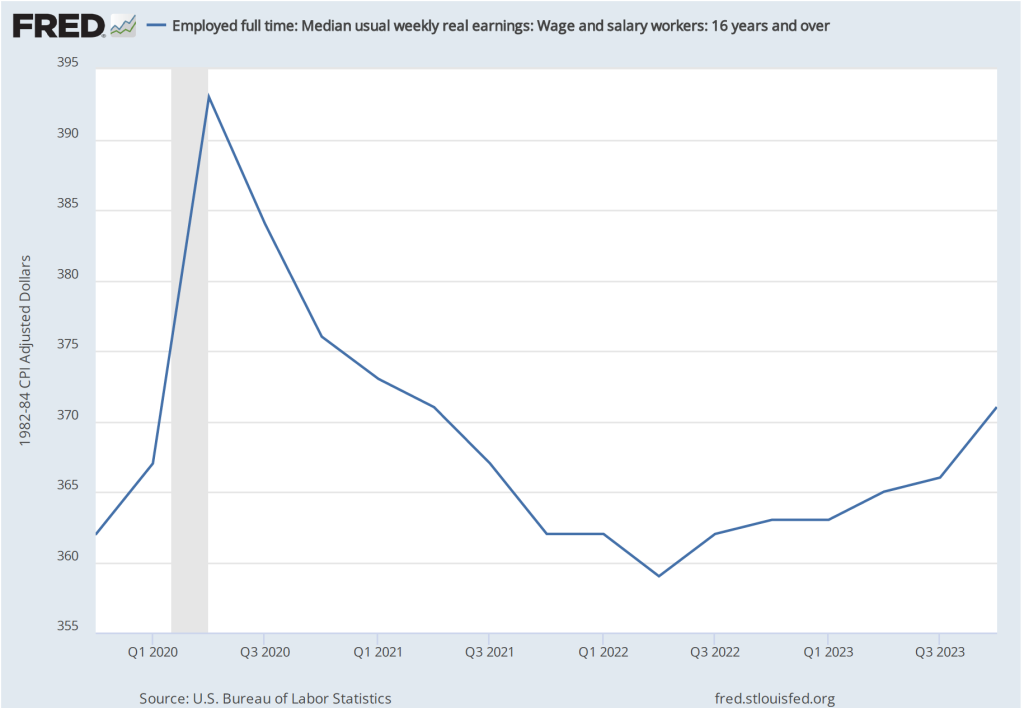

Median weekly real earnings, because it is calculated as a median rather than as an average (or mean), is less subject to composition effects than is real average hourly earnings. Median weekly real earnings increased sharply between February and April of 2020 before declining through June 2022. Earnings then gradually increased. In February 2024 they were 2.5 percent higher than in February 2020.

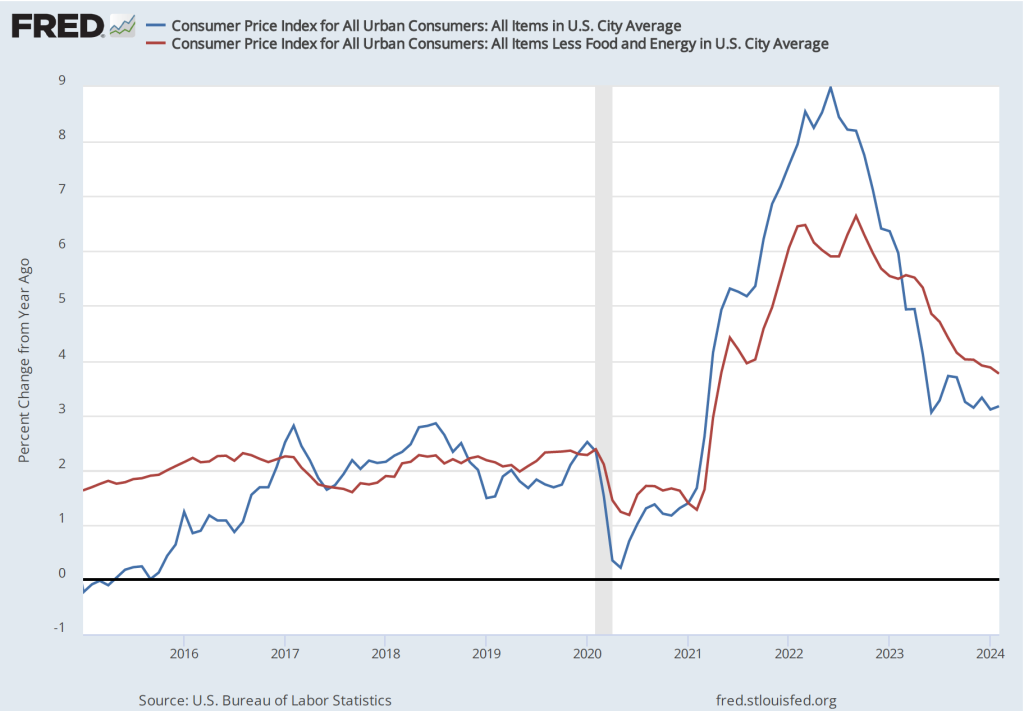

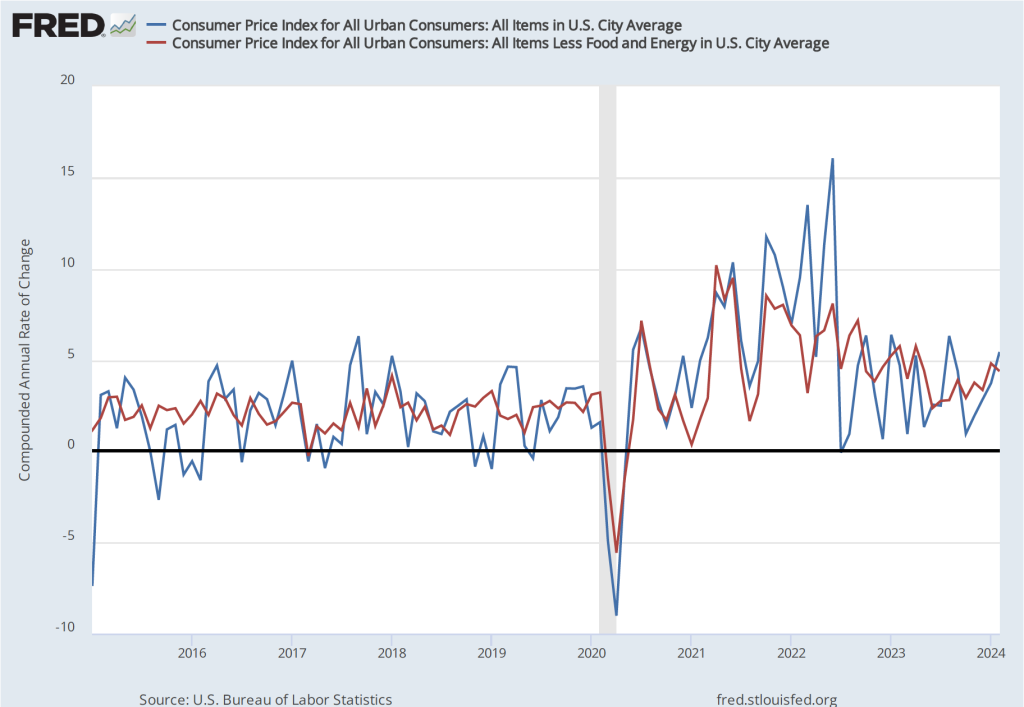

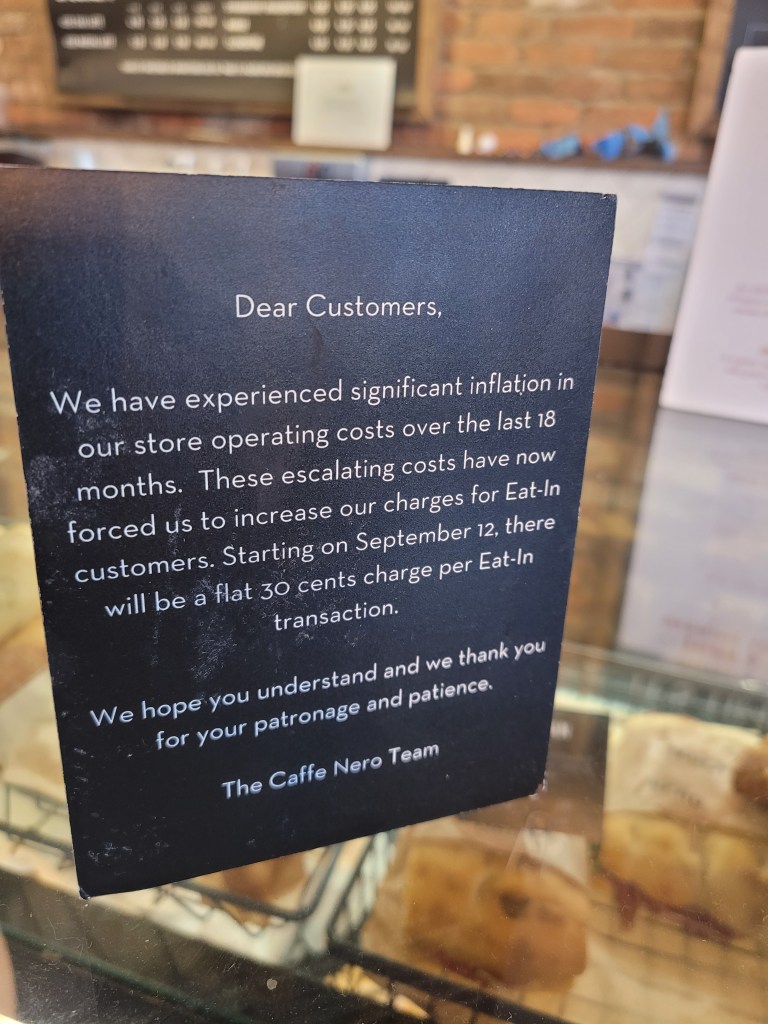

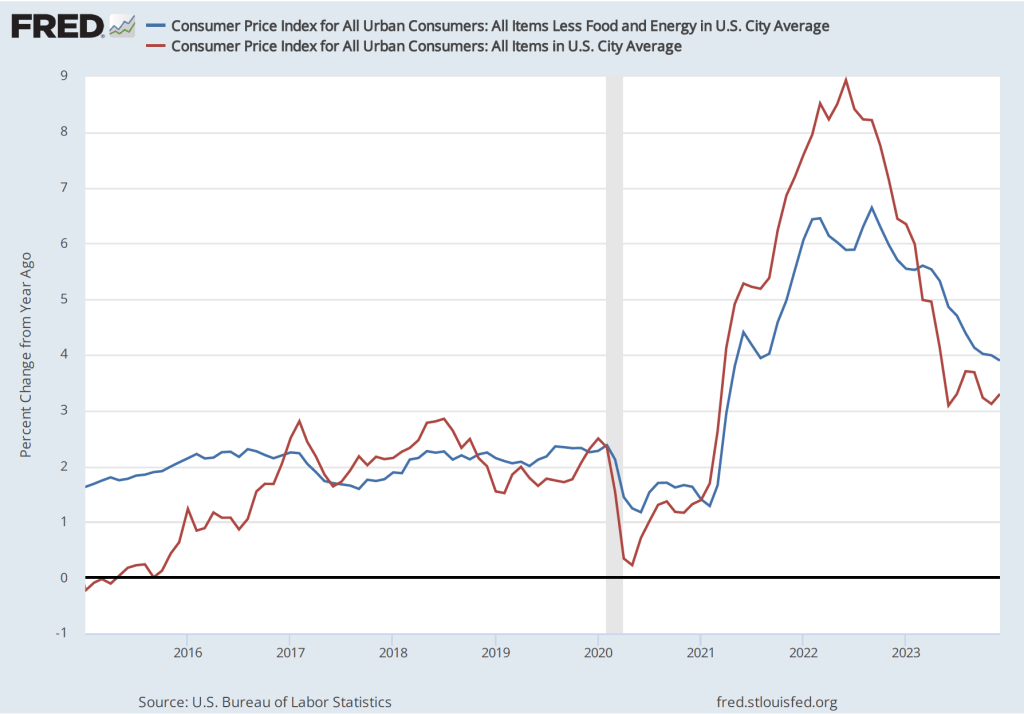

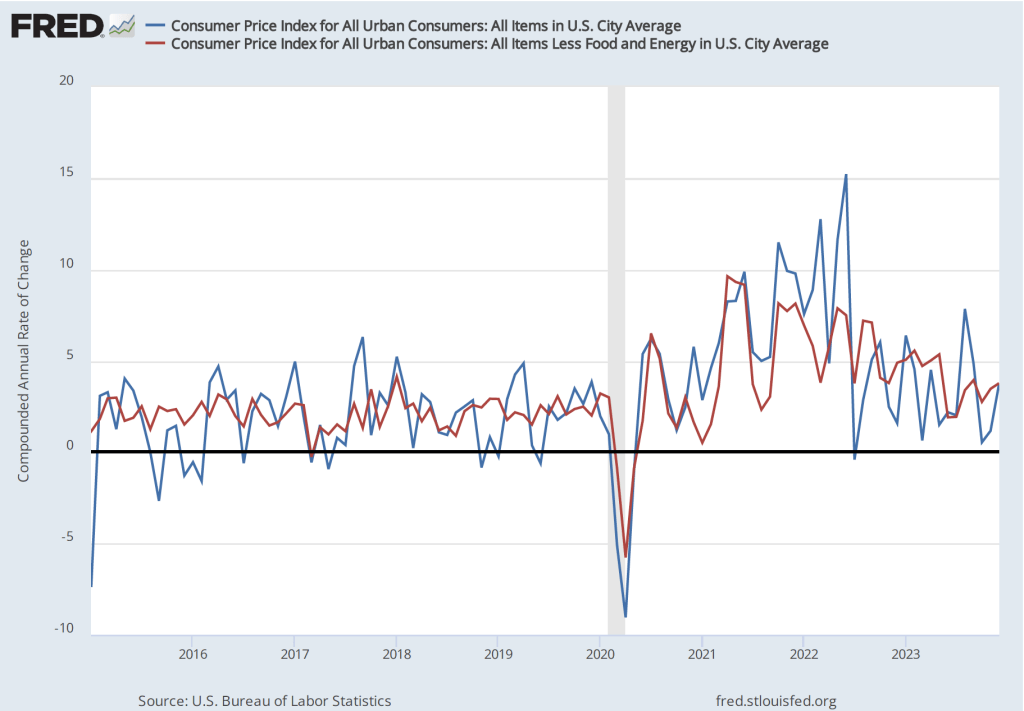

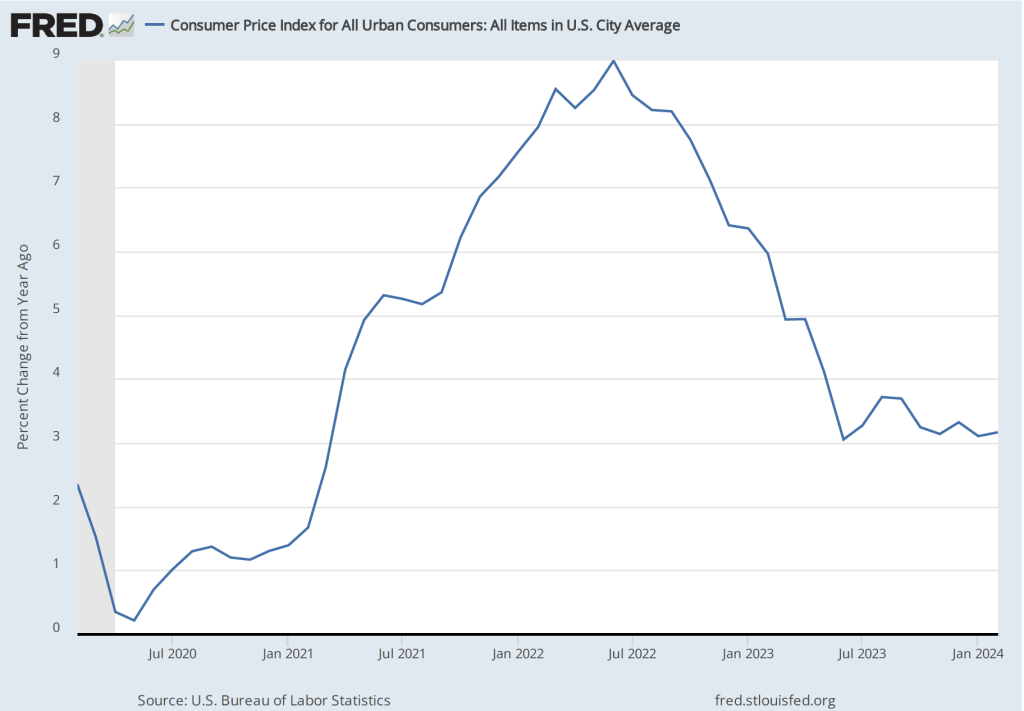

Inflation

The inflation rate most commonly mentioned in media reports is the percentage change in the CPI from the same month in the previous year. The following figure shows that inflation declined from February to May 2020. Inflation then began to rise slowly before rising rapidly beginning in the spring of 2021, reaching a peak in June 2022 at 9.0 percent. That inflation rate was the highest since November 1981. Inflation then declined steadily through June 2023. Since that time it has fluctuated while remaining above 3 percent.

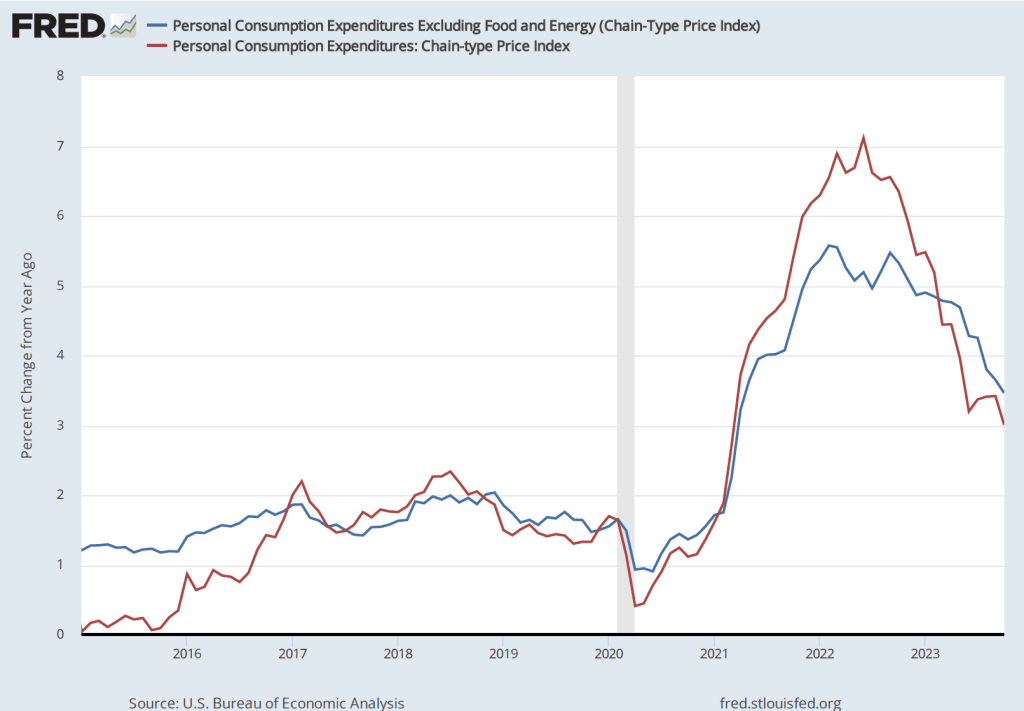

As we discuss in Macroeconomics, Chapter 15, Section 15.5 (Economics, Chapter 25, Section 25.5), the Federal Reserve gauges its success in meeting its goal of an inflation rate of 2 percent using the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index. The following figure shows that PCE inflation followed roughly the same path as CPI inflation, although it reached a lower peak and had declined below 3 percent by November 2023. (A more detailed discussion of recent inflation data can be found in this post and in this post.)

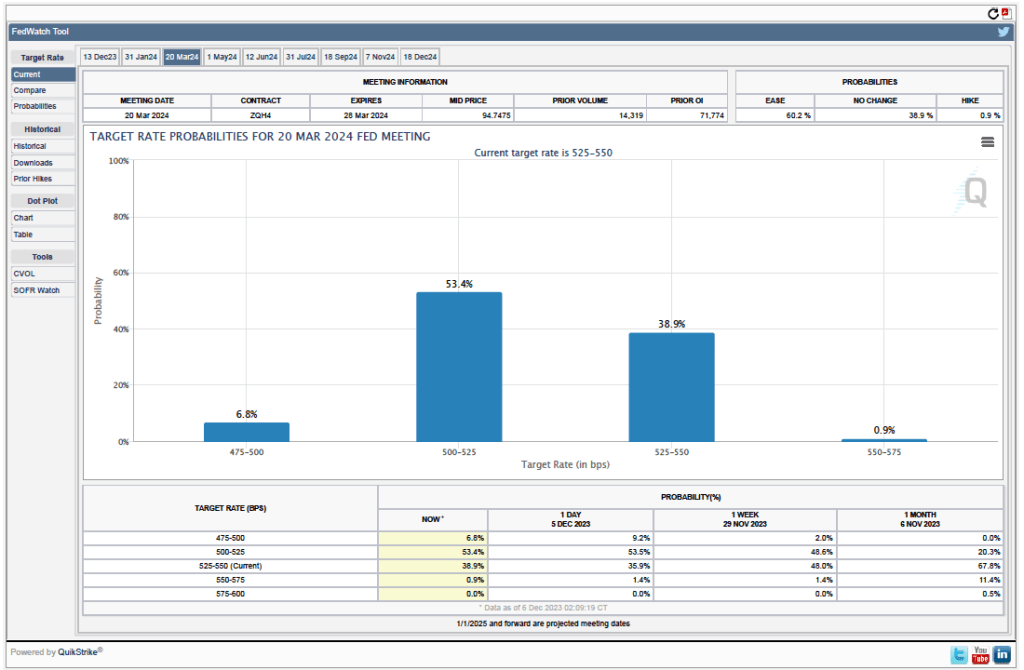

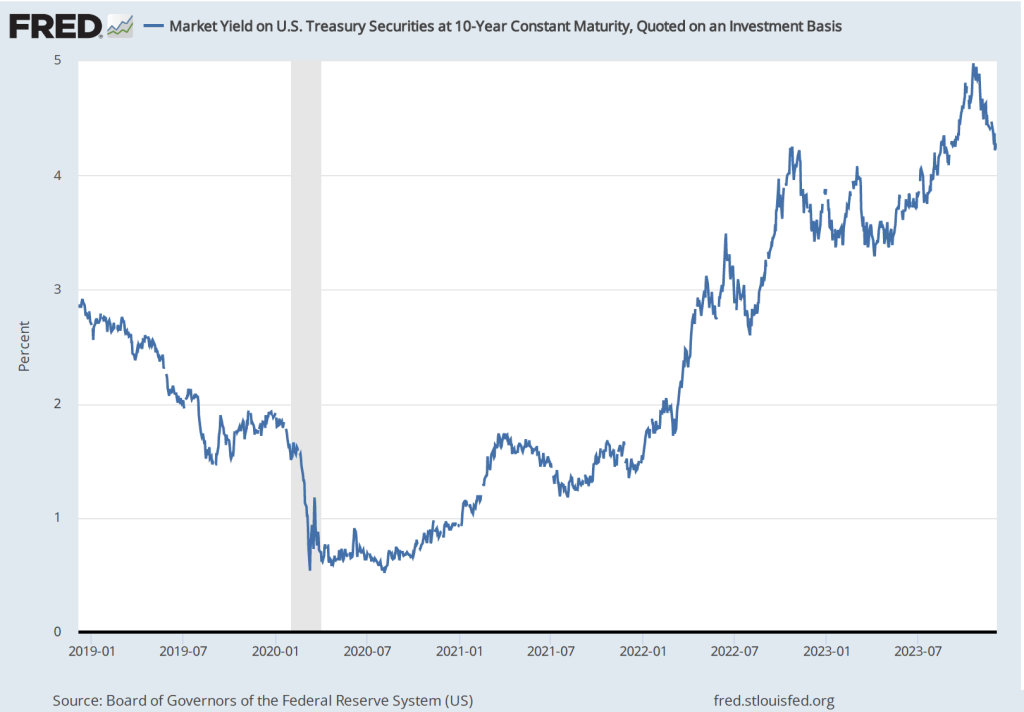

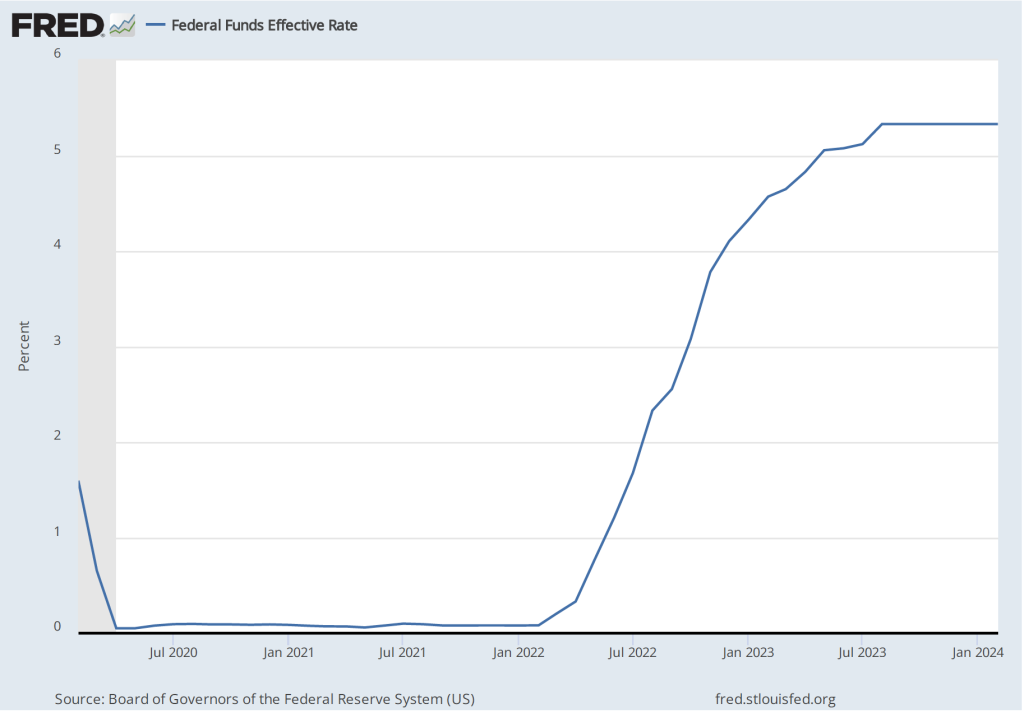

Monetary Policy

The following figure shows the effective federal funds rate, which is the rate—nearly always within the upper and lower bounds of the Fed’s target range—that prevails during a particular period in the federal funds market. In March 2020, the Fed cut its target range to 0 to 0.25 percent in response to the economic disruptions caused by the pandemic. It kept the target unchanged until March 2022 despite the sharp increase in inflation that had begun a year earlier. The members of the Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) had initially hoped that the surge in inflation was largely caused by disuptions to supply chains and would be transitory, falling as supply chains returned to normal. Beginning in March 2022, the FOMC rapidly increased its target range in response to continuing high rates of inflation. The targer range reached 5.25 to 5.50 percent in July 2023 where it has remained through March 2024.

Although the money supply is no longer the focus of monetary policy, some economists have noted that the rate of growth in the M2 measure of the money supply increased very rapidly just before the inflation rate began to accelerate in the spring of 2021 and then declined—eventually becoming negative—during the period in which the inflation rate declined.

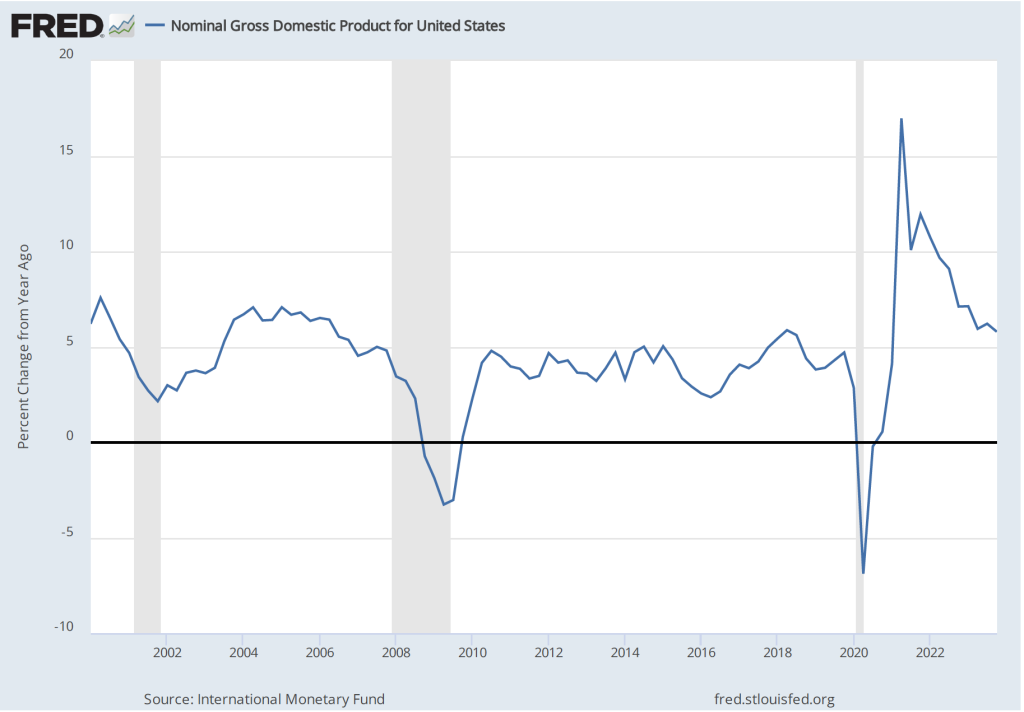

As we discuss in the new 9th edition of Macroeconomics, Chapter 15, Section 15.5 (Economics, Chapter 25, Section 25.5), some economists believe that the FOMC should engage in nominal GDP targeting. They argue that this approach has the best chance of stabilizing the growth rate of real GDP while keeping the inflation rate close to the Fed’s 2 percent target. The following figure shows the economy experienced very high rates of inflation during the period when nominal GDP was increasing at an annual rate of greater than 10 percent and that inflation declined as the rate of nominal GDP growth declined toward 5 percent, which is closer to the growth rates seen during the 2000s. (This figure begins in the first quarter of 2000 to put the high growth rates in nominal GDP of 2021 and 2022 in context.)

Fiscal Policy

As we discuss in the new 9th edition of Macroeconomics, Chapter 15 (Economics, Chapter 25), in response to the Covid pandemic Congress and Presidents Trump and Biden implemented the largest discretionary fiscal policy actions in U.S. history. The resulting increases in spending are reflected in the two spikes in federal government expenditures shown in the following figure.

The initial fiscal policy actions resulted in an extraordinary increase in federal expenditures of $3.69 trillion, or 81.3 percent, from the first quarter to the second quarter of 2020. This was followed by an increase in federal expenditures of $2.31 trillion, or 39.4 percent, from the fourth quarter of 2020 to the first quarter of 2021. As we recount in the text, there was a lively debate among economists about whether these increases in spending were necessary to offest the negative economic effects of the pandemic or whether they were greater than what was needed and contributed substantially to the sharp increase in inflation that began in the spring of 2021.

Saving

As a result of the fiscal policy actions of 2020 and 2021, many households received checks from the federal government. In total, the federal government distributed about $80o billion directly to households. As the figure shows, one result was to markedly increase the personal saving rate—measured as personal saving as a percentage of disposable personal income—from 6.4 percent in December 2019 to 22.0 in April 2020. (The figure begins in January 2020 to put the size of the spike in the saving rate in perspective.)

The rise in the saving rate helped households maintain high levels of consumption spending, particularly on consumer durables such as automobiles. The first of the following figure shows real personal consumption expenditures and the second figure shows real personal consumption expenditures on durable goods.

Taken together, these data provide an overview of the momentous macroeconomic events of the past four years.