Photo of the Internal Revenue Service building in Washington, DC from the Associated Press via the Wall Street Journal

The following op-ed by Glenn first appeared in the Wall Street Journal.

The GOP Tax Bill Could Solve the Tariff Problem

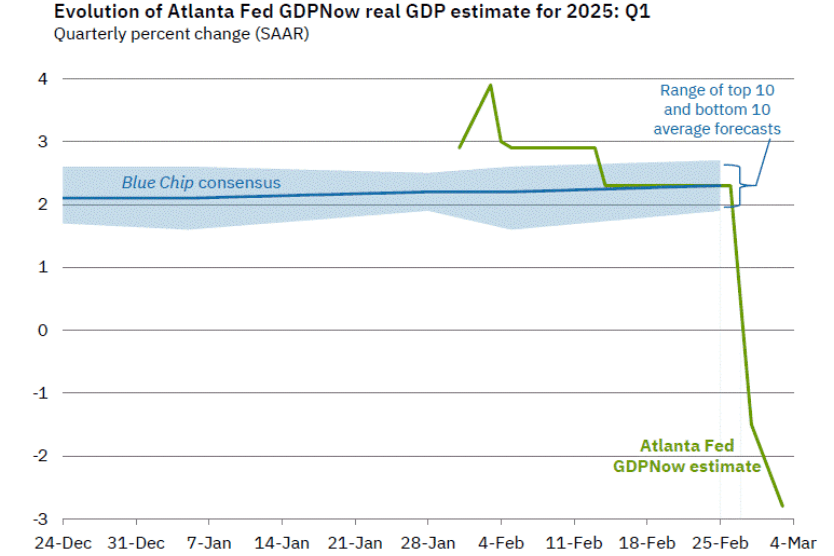

The economy and financial markets nervously await the July 8 end of the 90-day pause of the Trump administration’s “reciprocal” tariffs. But four days earlier, Republicans can allay those fears with a pro-growth policy that advances President Trump’s Made in America agenda without tariffs. The fix: tax reform.

July 4 is the date that Treasury Secretary Bessent has predicted Congress and the White House will have ready a 2.0 version of the landmark Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017, or TCJA. Without congressional action, some of these reforms will expire at the end of 2025, killing changes that still benefit the economy. Corporate tax changes, in particular, boosted investment and growth. These should remain the focal point of this next tax bill—for many reasons. Done right, corporate tax reform could advance President Trump’s goal to bring investment to American production without using economy-roiling tariffs. Call it TCJA+.

Renewing some parts of the original TCJA will help investment in the U.S. The 2017 reform offered incentives for investment in new businesses by allowing them to expense the cost of assets, rather than writing them off over time. But these benefits were set to be phased out from 2023 to 2026, removing a key pro-growth element of the earlier law.

Then there are two new provisions Republicans should add to secure Mr. Trump’s goal to have more made in America. Both were in the original 2016 House Republican tax reform blueprint.

First, Congress should change business taxation from the current income tax to a cash-flow tax, which taxes a firm’s revenue, minus all its expenses, including investment. Long championed by economists and tax-law experts, a cash-flow tax would allow businesses to expense investment immediately. It would also disallow nonfinancial companies from making interest deductions, because unlike an income tax, a cash-flow tax treats debt and equity the same. This removes an important tax incentive for firms to allow themselves to be leveraged. A cash-flow tax is also much simpler than a corporate income tax, which requires complex depreciation schedules. Most important, the reform would stimulate business investment.

Second, legislators should add a border adjustment to corporate taxes. That would deny companies a tax deduction for expenses of inputs imported from abroad, while exempting U.S. exports from taxation. As the Trump administration has observed, other countries already use border adjustments in their value-added taxes on consumption. America uses a similar mechanism in state and local retail taxes, too. If you buy a kitchen appliance in New York, you pay New York sales tax, even if it was made in Ohio. Sales tax applies only where the good is sold, not where it originates.

Though distinct from tariffs, border adjustments can promote domestic production. Adding a border adjustment to the federal corporate tax would eliminate any extra tax businesses suffer now simply as a consequence of producing in the U.S. Though the 2017 law made the U.S. tax system more globally competitive by lowering the corporate income tax rate from 35% to 21%, it’s still higher than in many other countries, which attract production with low cost. A border adjustment would remove this incentive for American firms to locate profits or activities abroad, while increasing incentives for non-U.S. firms to locate activities within our borders.

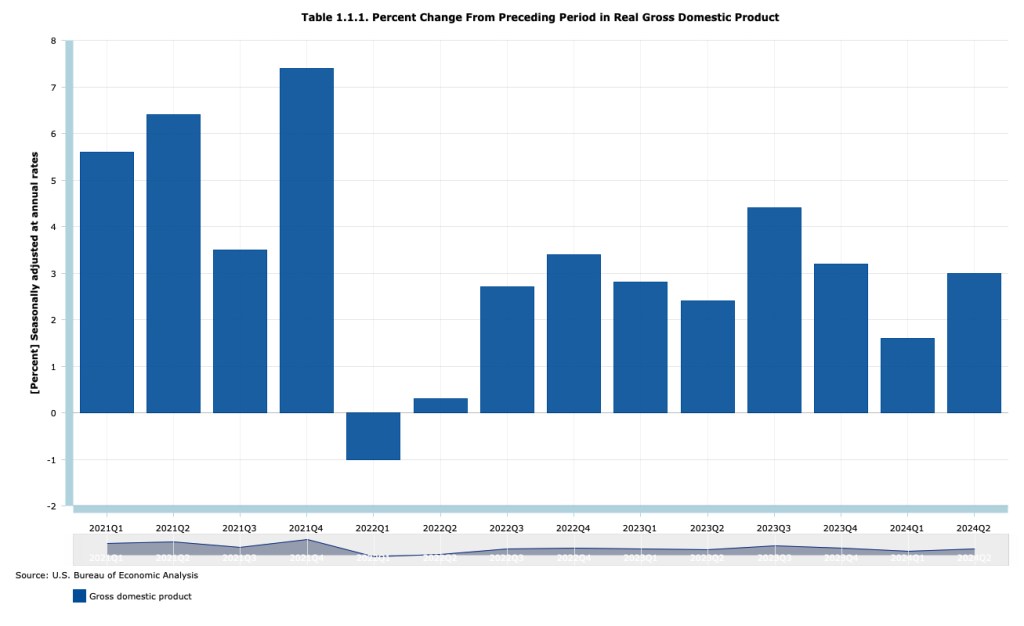

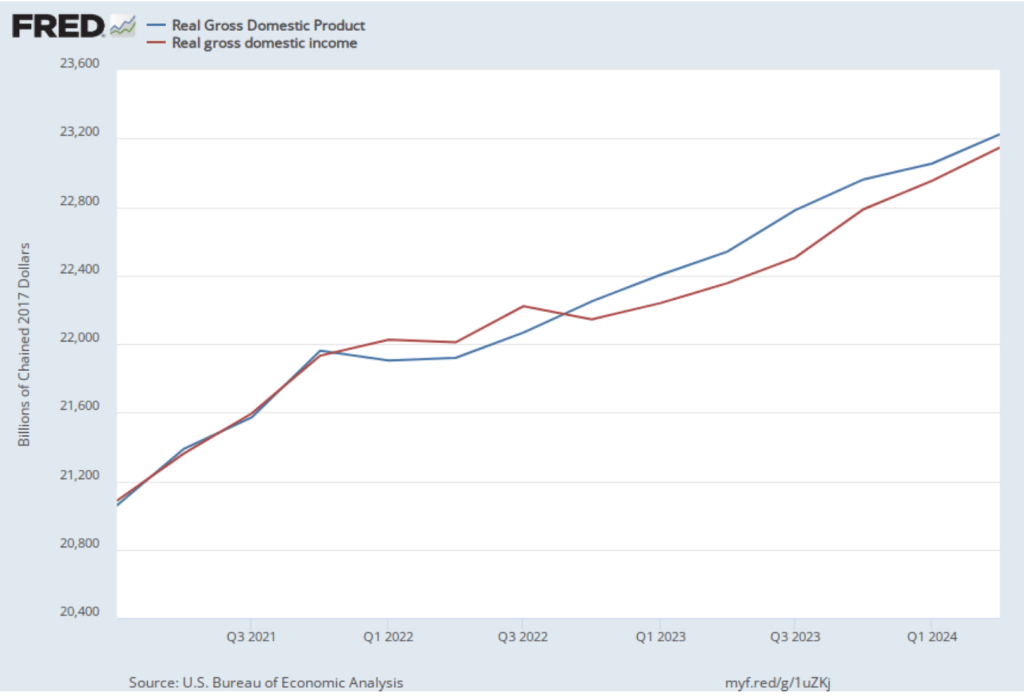

As with the original pro-investment features in the 2017 law, this TCJA+ reform would increase investment and incomes—and thereby revenue. For the original TCJA, when the Congressional Budget Office included the macroeconomic effects of higher incomes buoyed by the reforms’ pro-growth elements, the CBO reduced the estimated revenue loss from the tax cuts by almost 30%. Changing the corporate income tax to a cash-flow levy would similarly increase revenue by removing taxes on what economists call the “normal return” on investment, or the cost of capital. Companies would instead pay only on profits above this amount. A border adjustment can likewise raise substantial revenue over the next decade because imports (which would receive no deduction) are larger than exports (which would no longer be taxed).

The higher revenue these two TCJA+ provisions promise could be used to lower the tax rate on business cash flow or to fund other tax-policy objectives. Importantly, that revenue can replace revenue raised from the tariffs the Trump administration had planned to implement on July 8. These two tax provisions would accomplish the president’s America-first and revenue objectives without destabilizing businesses with whipsawing tariffs.

Finally, TCJA+ would offer another big benefit: It would move the U.S. toward independence from political meddling in the economy via targeted protection or subsidies. This added predictability and breathing room for investment would be one more reason to produce in America. Pluses indeed.