Supports: Microeconomics and Economics, Chapter 6.

Photo from the New York Times.

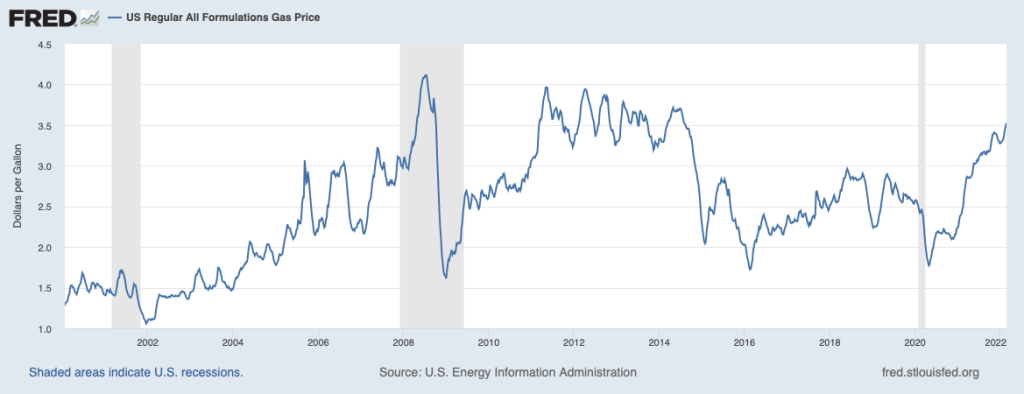

Blogger Matthew Yglesias made the following observation in a recent post: “If you look at gasoline prices, it’s obvious that if fuel gets way more expensive next week, most people are just going to have to pay up. But if you compare the US versus Europe, it’s also obvious that the structurally higher price of gasoline over there makes a massive difference: They have lower rates of car ownership, drive smaller cars, and have a higher rate of EV adoption.” (The blog post can be found here, but may require a subscription.)

- What does Yglesias mean by Europe having a “structurally higher price” of gasoline?

- Assuming Yglesias’s observations are correct, what can we conclude about the price elasticity of the demand for gasoline in the short run and in the long run?

- Currently, the federal government imposes a tax of 18.4 cents per gallon of gasoline. Suppose that Congress increases the gasoline tax to 28.4 cents per gallon. Again assuming that Yglesias’s observations are correct, would you expect that the incidence of the tax would be different in the long run than in the short run? Briefly explain.

- Would you expect the federal government to collect more revenue as a result of the 10 cent increase in the gasoline tax in the short run or in the long run? Briefly explain.

Solving the Problem

Step 1: Review the chapter material. This problem is about the determinants of the price elasticity of demand and the effect of the value of the price elasticity of demand on the incidence of a tax, so you may want to review Chapter 6, Section 6.2 and Solved Problem 6.5. (Note that a fuller discussion of the effect of the price elasticity of demand on tax incidence appears in Chapter 17, Section 17.3.)

Step 2: Answer part a. by explaining what Yglesias means when he writes that Europe has a “structurally higher” price of gasoline. Judging from the context, Yglesias is saying that European gasoline prices are not just temporarily higher than U.S. gasoline prices but have been higher over the long run.

Step 3: Answer part b. by expalining what we can conclude from Yglesias’s observations about the price elasticity of demand for gasoline in the short run and in the long run. When Yeglesias is referring to gasoline prices rising “next week,” he is referring to the short run. In that situation he says “most people are going to have to pay up.” In other words, the increase in price will lead to only a small decrease in the quantity demanded, which means that in the short run, the demand for gasoline is price inelastic—the percentage change in the quantity demanded will be smaller than the percentage change in the price.

Because he refers to high gasoline prices in Europe being structural, or high for a long period, he is referring to the long run. He notes that in Europe people have responded to high gasoline prices by owning fewer cars, owning smaller cars, and owning more EVs (electric vehicles) than is true in the United States. Each of these choices by European consumers results in their buying much less gasoline as a result of the increase in gasoline prices. As a result, in the long run the demand for gasoline is price elastic—the percentage change in the quantity demanded will be greater than the percentage change in the price.

Note that these results are consistent with the discussion in Chapter 6 that the more time that passes, the more price elastic the demand for a product becomes.

Step 4: Answer part c. by explaining how the incidence of the gasoline tax will be different in the long run than in the short run. Recall that tax incidence refers to the actual division of the burden of a tax between buyers and sellers in a market. As the figure in Solved Problem 6.5 illustrates, a tax will result in a larger increase in the price that consumers pay for a product in the situation when demand is price inelastic than when demand is price elastic. The larger the increase in the price that consumers pay, the larger the share of the burden of the tax that consumers bear. So, we can conclude that the tax incidence of the gasoline tax will be different in the short run than in the long run: In the short run, more of the burden of the tax is borne by consumers (and less of the burden is borne by suppliers); in the long run, less of the burden of the tax is borne by consumers (and more of the burden is borne by suppliers).

Step 5: Answer part d. by explaining whether you would expect the federal government to collect more revenue as a result of the 10 cent increase in the gasoline tax in the short run or in the long run. The revenue the federal government collects is equal to the 10 cent tax multiplied by the quantity of gallons sold. As the figure in Solved Problem 6.5 illustrates, a tax will result in a smaller decrease in the quantity demanded when demand is price inelastic than when demand is price elastic. Therefore, we would expect that the federal government will collect more revenue from the tax in the short run than in the long run.