Image of “a family shopping in a supermarket” generated by ChatGTP 4o.

In testifying before Congress this week, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell indicated that the Fed’s policy-making Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) was becoming more concerned that it not be too late in reducing its target for the federal funds rate:

“[I]n light of the progress made both in lowering inflation and in cooling the labor market over the past two years, elevated inflation is not the only risk we face. Reducing policy restraint too late or too little could unduly weaken economic activity and employment.”

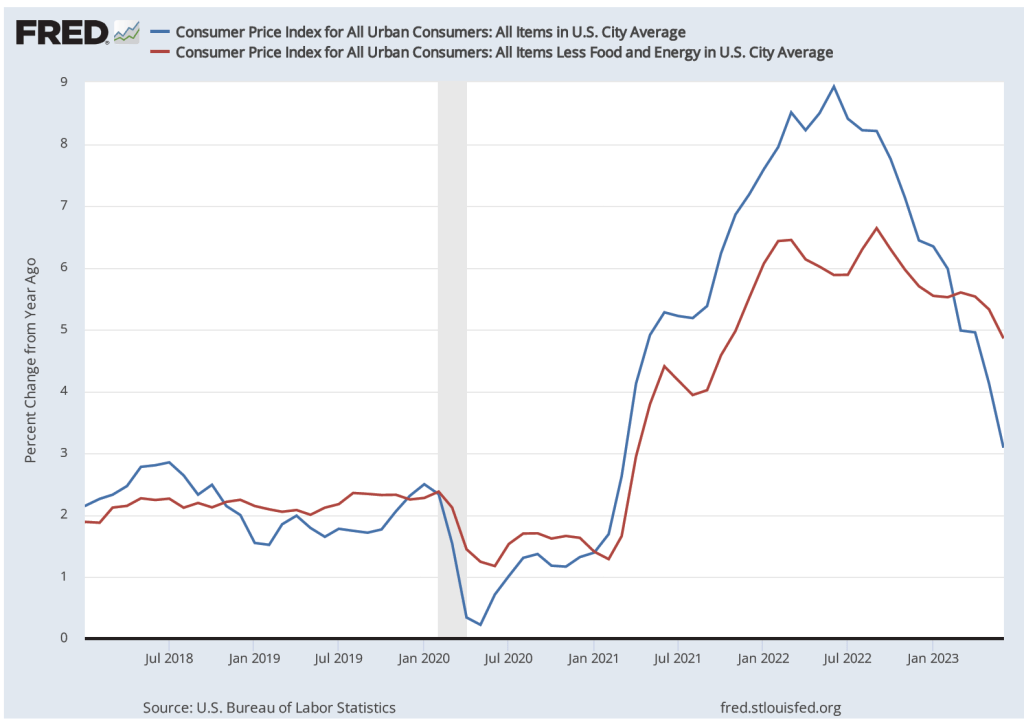

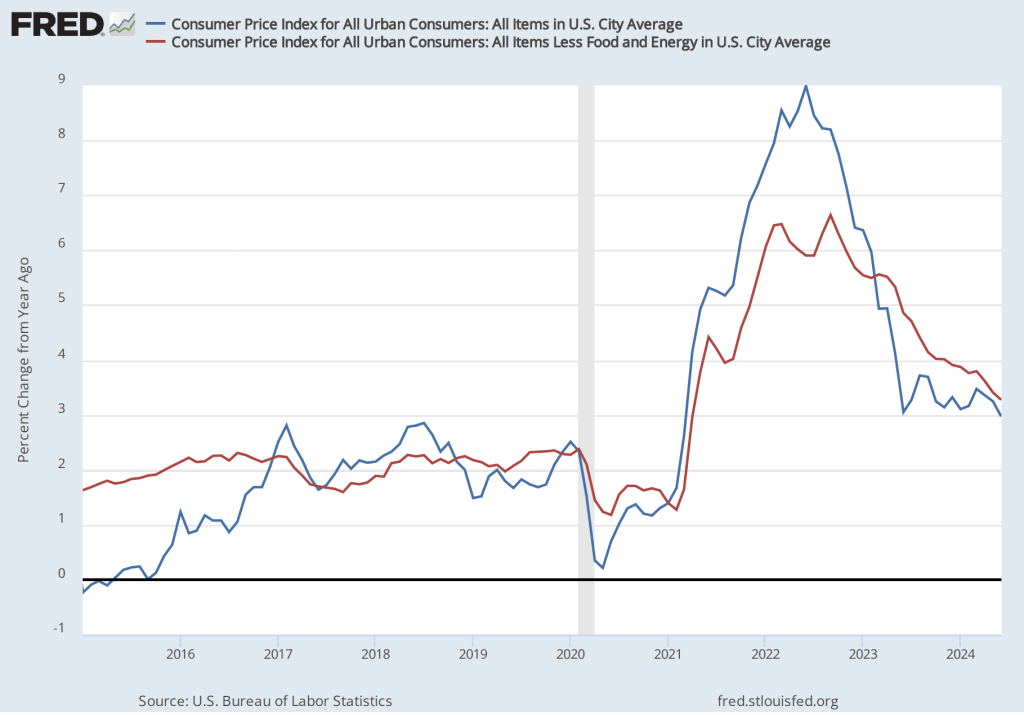

Powell also noted that: “more good data would strengthen our confidence that inflation is moving sustainably toward 2 percent.” Today (July 11), Powell received more good data as the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released its monthly report on the consumer price index (CPI), which showed a further slowing in inflation.

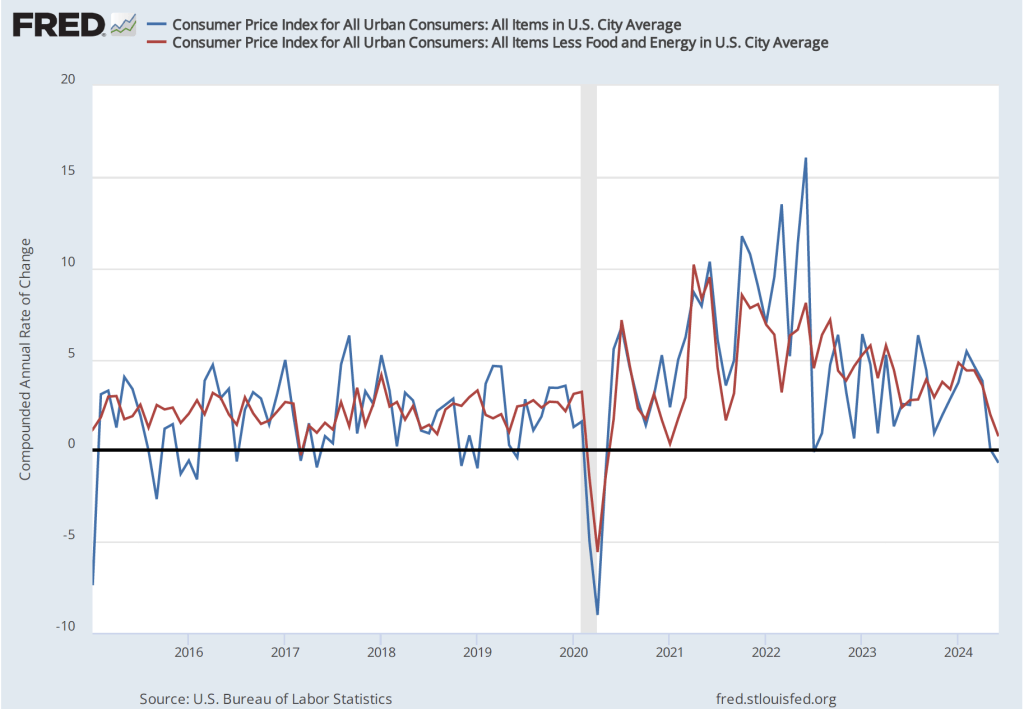

As the following figure shows, the inflation rate for June measured by the percentage change in the CPI from the same month in the previous month—headline inflation (the blue line)—was 3.o percent down from 3.3 percent in May. Core inflation (the red line)—which excludes the prices of food and energy—was 3.3 percent in June, down from 3.4 percent in May.

As the following figure shows, if we look at the 1-month inflation rate for headline and core inflation—that is the annual inflation rate calculated by compounding the current month’s rate over an entire year—the declines in the inflation rate are much larger. Headline inflation (the blue line) declined from 0.1 percent in May to –0.7 in June—consumer prices fell during June. Core inflation (the red line) declined from 2.0 percent in May to 0.8 percent in June. Overall, we can say that inflation has cooled further in June, bringing the U.S. economy closer to a soft landing—with the annual inflation rate returning to the Fed’s 2 percent target without the economy being pushed into a recession. (Note, though, that the Fed uses the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index, rather than the CPI in evaluating whether it is hitting its 2 percent inflation target.)

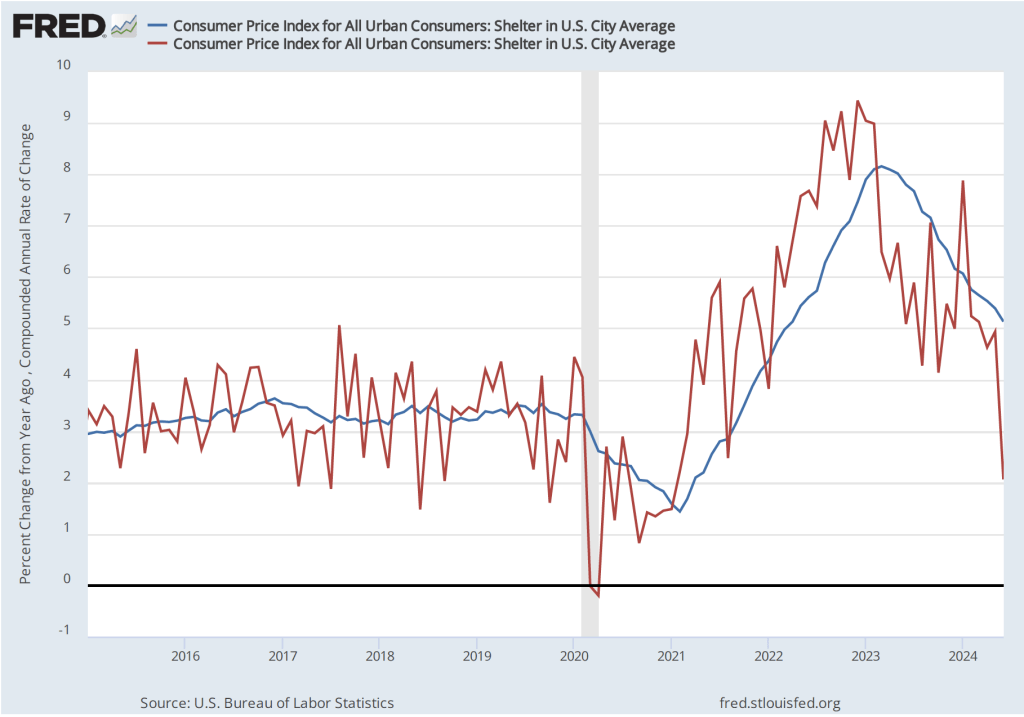

The FOMC has been looking closely at inflation in the price of shelter. The price of “shelter” in the CPI, as explained here, includes both rent paid for an apartment or house and “owners’ equivalent rent of residences (OER),” which is an estimate of what a house (or apartment) would rent for if the owner were renting it out. OER is included to account for the value of the services an owner receives from living in an apartment or house.

As the following figure shows, inflation in the price of shelter has been a significant contributor to headline inflation. The blue line shows 12-month inflation in shelter and the red line shows 1-month inflation in shelter. Twelve-month inflation in shelter continued its decline that began in the spring of 2023. One-month inflation in shelter declined substantially from 4.9 percent in May to 2.1 percent in June. These values indicate that the price of shelter may no longer be a significant driver of headline inflation.

Finally, in order to get a better estimate of the underlying trend in inflation, some economists look at median inflation and trimmed mean inflation. Meadin inflation is calculated by economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland and Ohio State University. If we listed the inflation rate in each individual good or service in the CPI, median inflation is the inflation rate of the good or service that is in the middle of the list—that is, the inflation rate in the price of the good or service that has an equal number of higher and lower inflation rates. Trimmed mean inflation drops the 8 percent of good and services with the higherst inflation rates and the 8 percent of goods and services with the lowest inflation rates.

As the following figure (from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland) shows, both median inflation (the brown line) and trimmed mean inflation (the blue line) were somewhat higher than either headline CPI inflation or core CPI inflation. One conclusion from these data is that headline and core inflation may be somewhat understating the underlying rate of inflation.

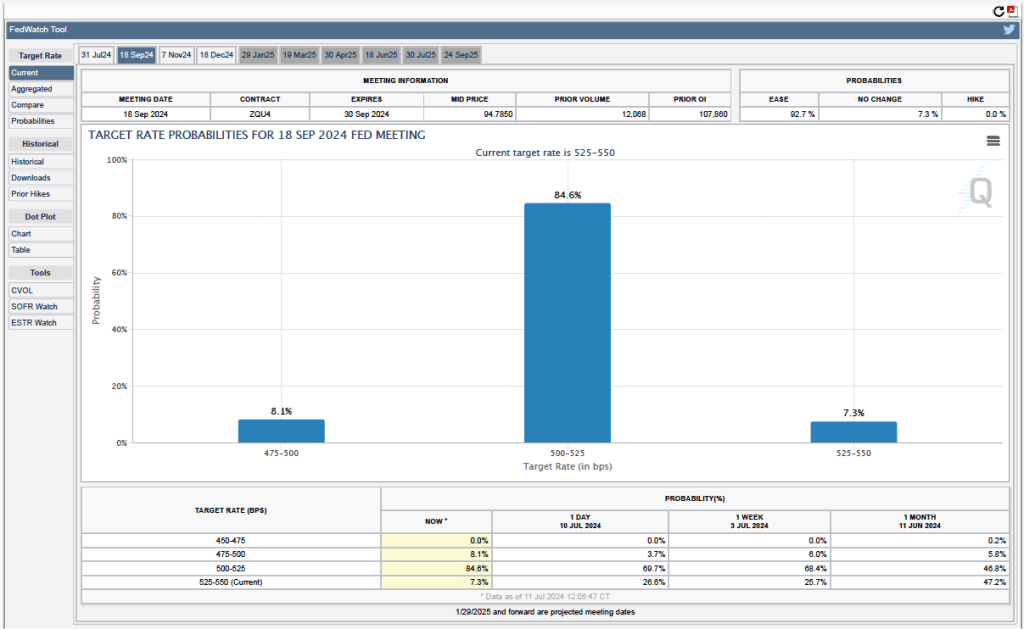

Financial markets are interpreting the most inflation and employment data as indicating that at its meeting on Septembe 17-18 the FOMC is likely to cut its target range for the federal funds rate from the current 5.25 percent to 5.50 to 5.00 percent to 5.25 percent.

Futures markets allow investors to buy and sell futures contracts on commodities–such as wheat and oil–and on financial assets. Investors can use futures contracts both to hedge against risk—such as a sudden increase in oil prices or in interest rates—and to speculate by, in effect, betting on whether the price of a commodity or financial asset is likely to rise or fall. (We discuss the mechanics of futures markets in Chapter 7, Section 7.3 of Money, Banking, and the Financial System.) The CME Group was formed from several futures markets, including the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, and allows investors to trade federal funds futures contracts. The data that result from trading on the CME indicate what investors in financial markets expect future values of the federal funds rate to be. The following chart from the CME’s FedWatch Tool shows the current values from trading of federal funds futures.

The probabilities in the chart reflect investors’ predictions of what the FOMC’s target for the federal funds rate will be after the committee’s September meeting. The chart indicates that investors assign a probability of only 8.1 percent to the FOMC leaving its federal funds rate target unchanged at its September meeting, but a 84.6 percent probability of the committee cutting its target by 0.25 percentage point (and a 7.3 percent probability of the committee cutting its target by 0.50 percent age point).