An image generated by GTP-4o of people going to work.

The Federal Reserve’s policymaking Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) has its next meeting on December 17-18. Although the committee is expected to lower its target range for the federal funds rate at that meeting, some members of the committee have been concerned that inflation has remained above the committee’s 2 percent annual target. For instance, in an interview on December 4, Fed Chair Jerome Powell said: “Growth is definitely stronger than we thought, and inflation is coming a little higher. The good news is that we can afford to be a little more cautious as we try to find [the] neutral [federal funds rate].”

This morning (December 6), the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released its “Employment Situation” report (often called the “jobs report”) for November. The report provided data indicating that the labor market remained strong—perhaps stronger than is consistent with the FOMC being willing to rapidly cut its federal funds rate target. The data in the October report (which we discussed in this blog post) were distorted by the effects of hurricanes and strikes. Today’s report indicated a bounce back in the labor market as many workers in areas affected by hurricanes returned to work and key strikes ended.

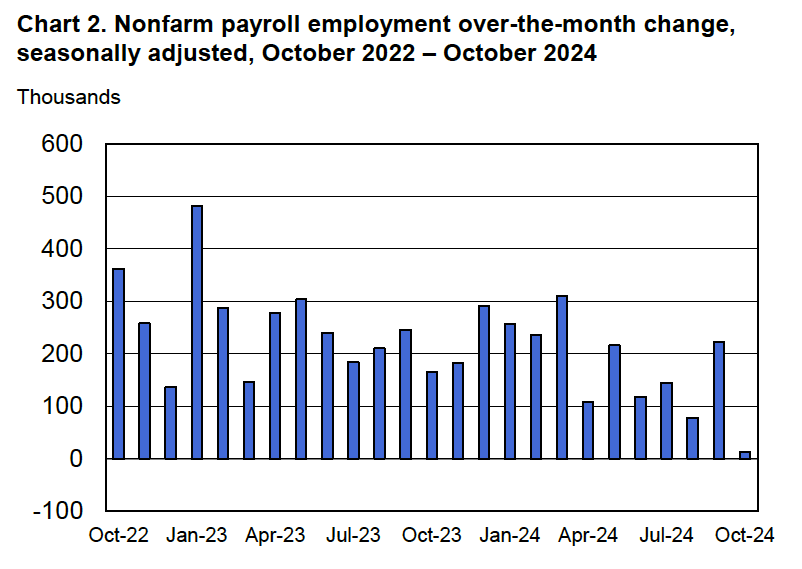

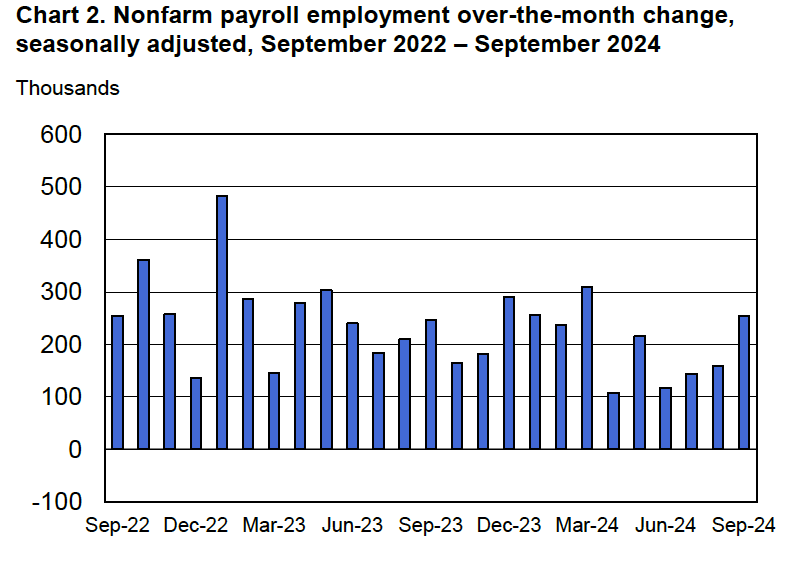

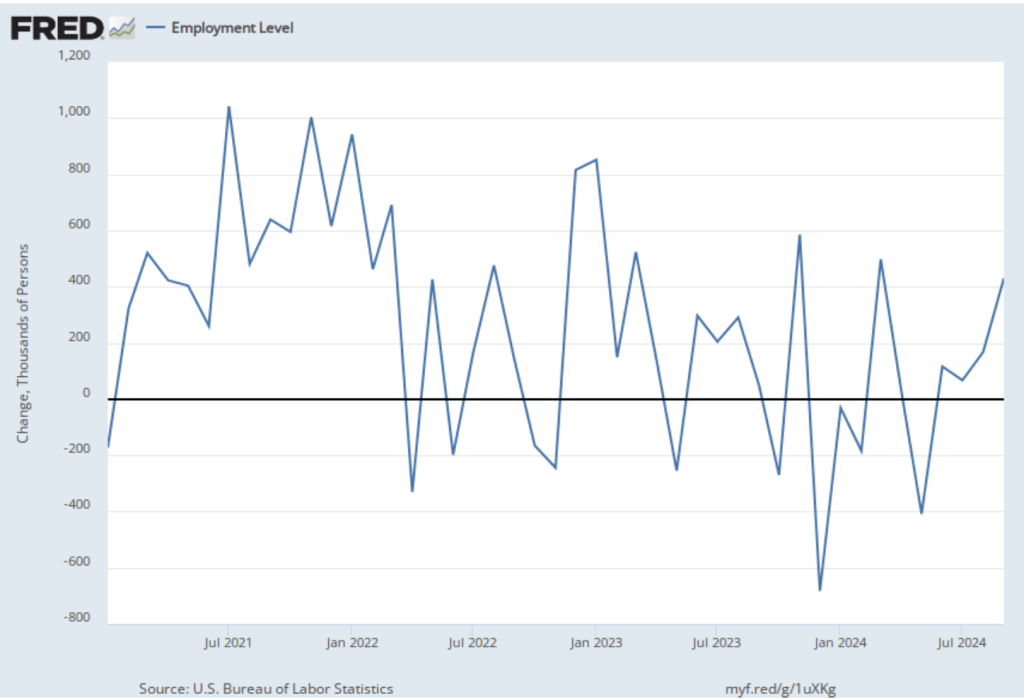

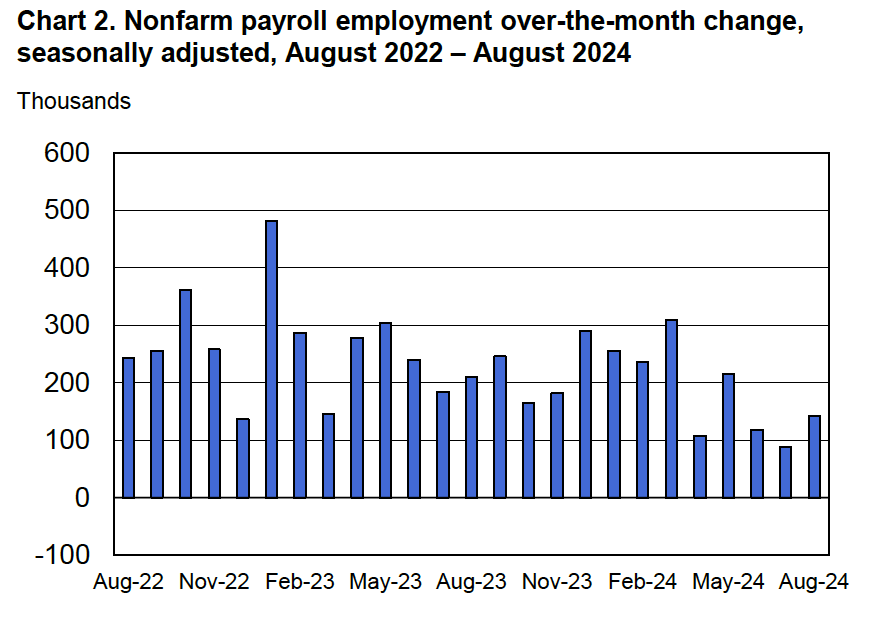

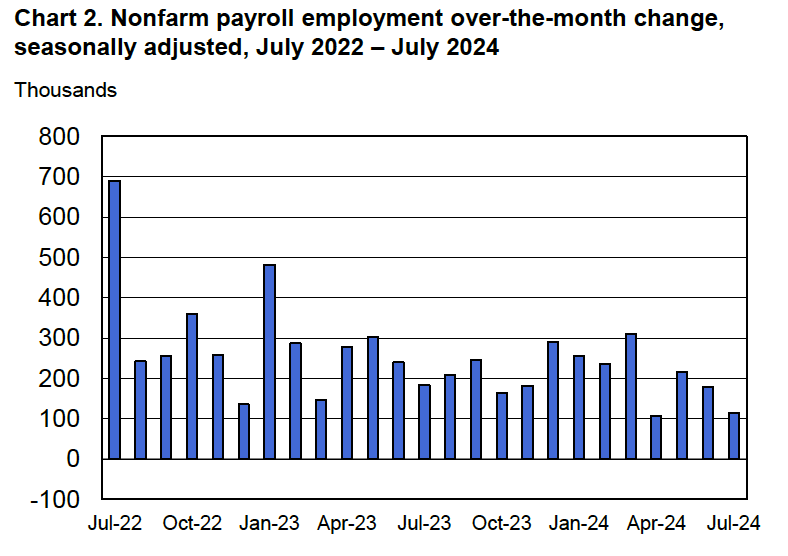

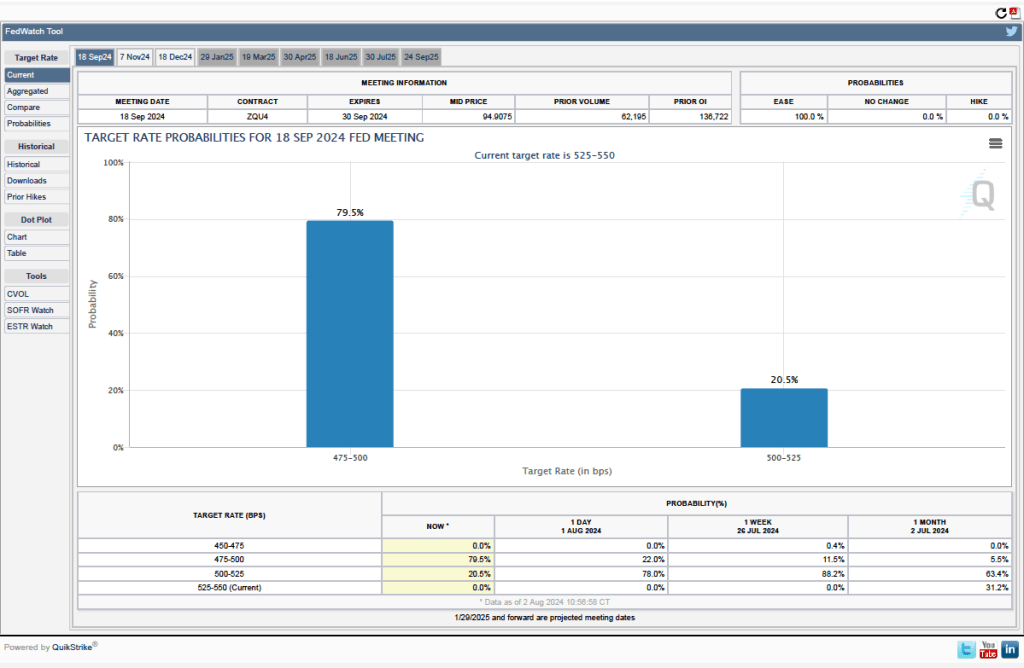

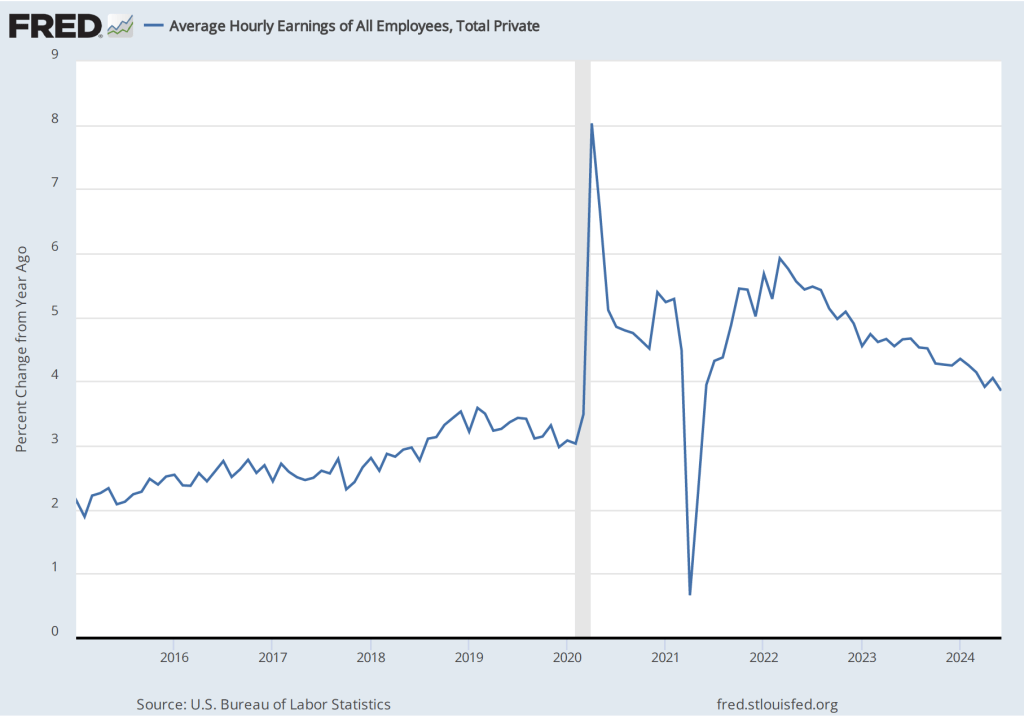

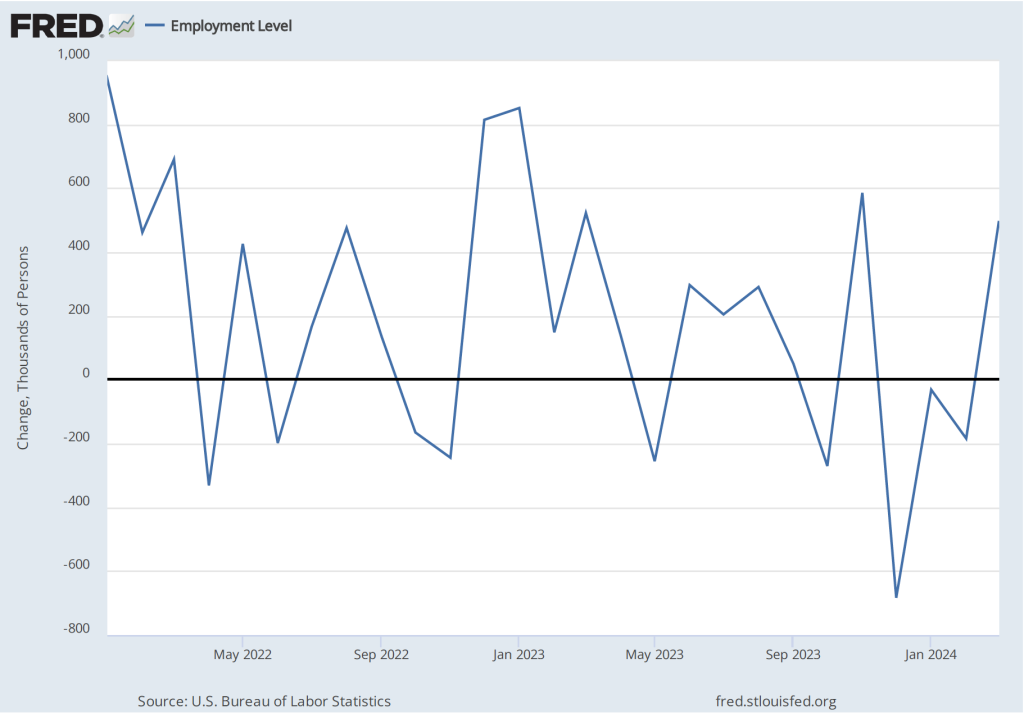

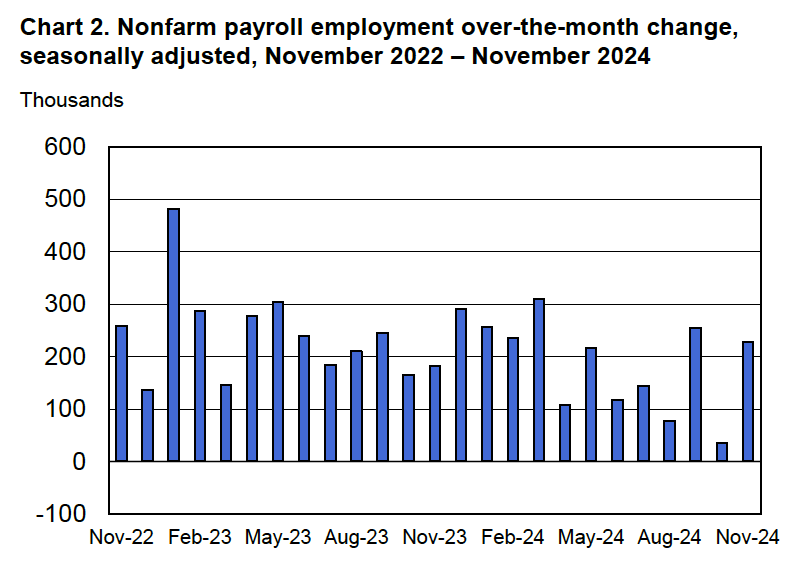

Economists who had been surveyed by the Wall Street Journal had forecast that payroll employment, as reported in the establishment survey, would increase by 214,000. The BLS reported that payroll employment in November had increased by 227,000, slightly above expectations. The unemployment rate—which is calculated from data in the household survey—was 4.2 percent, up slightly from 4.1 percent in October. In addition, the BLS revised upward its estimates of the employment increases in September and October by a total of 56,000. (The BLS notes that: “Monthly revisions result from additional reports received from businesses and government agencies since the last published estimates and from the recalculation of seasonal factors.”) The following figure, taken from the BLS report, shows the net changes in employment for each month during the past two years.

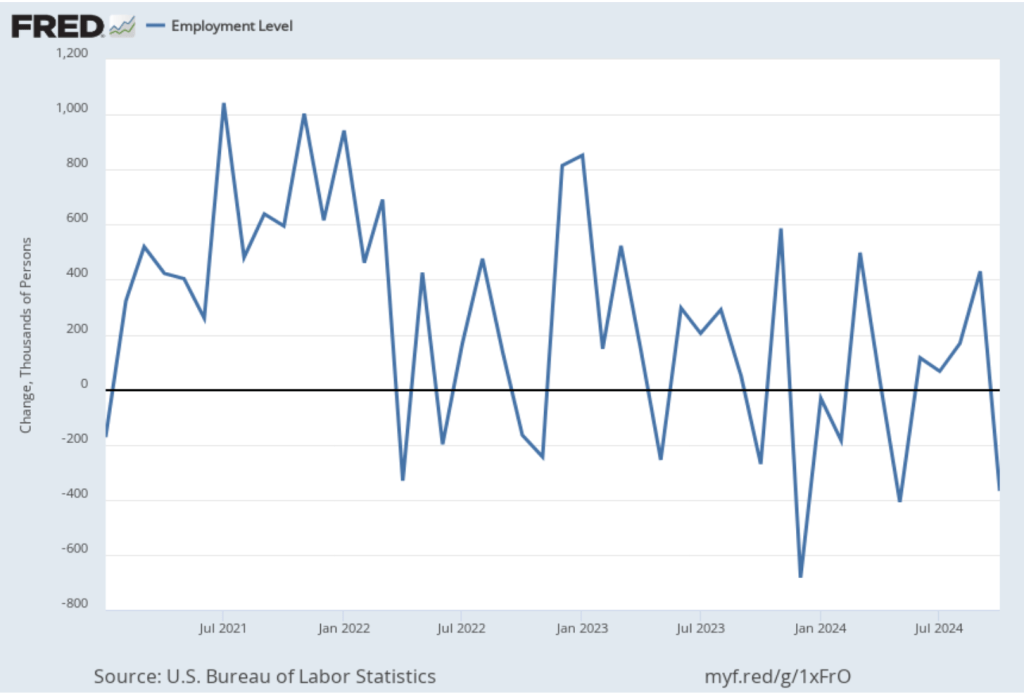

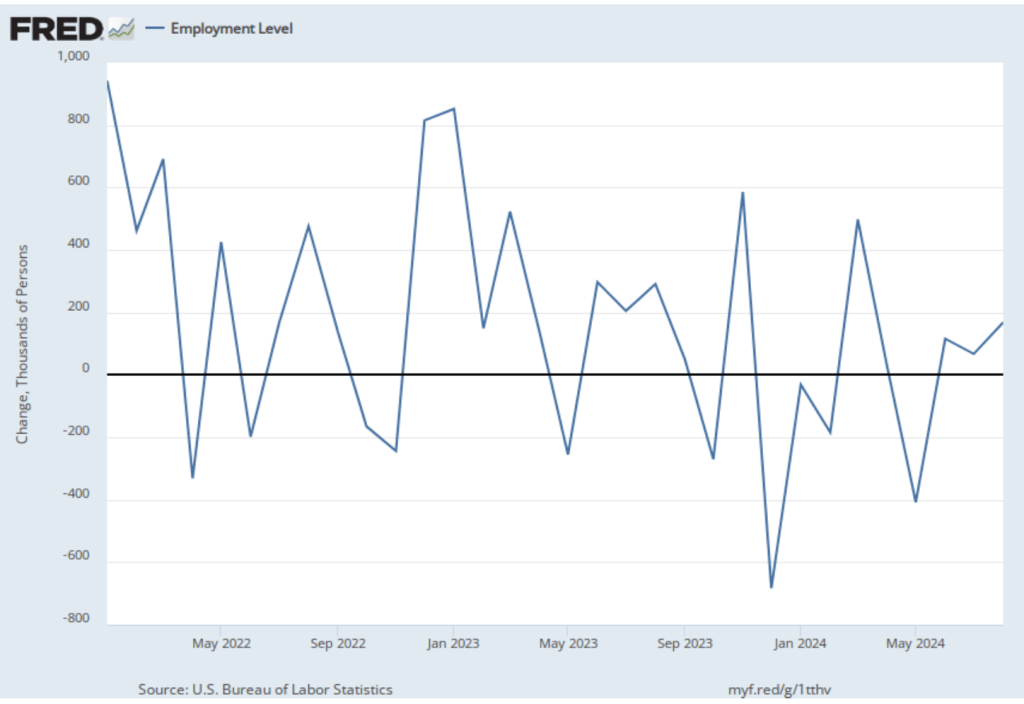

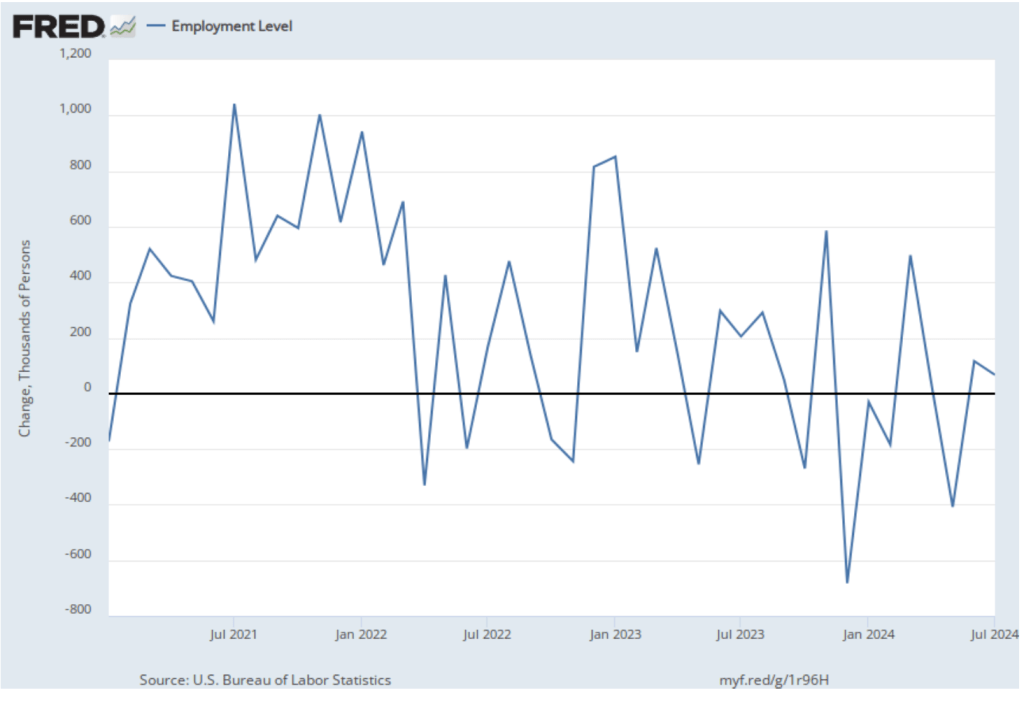

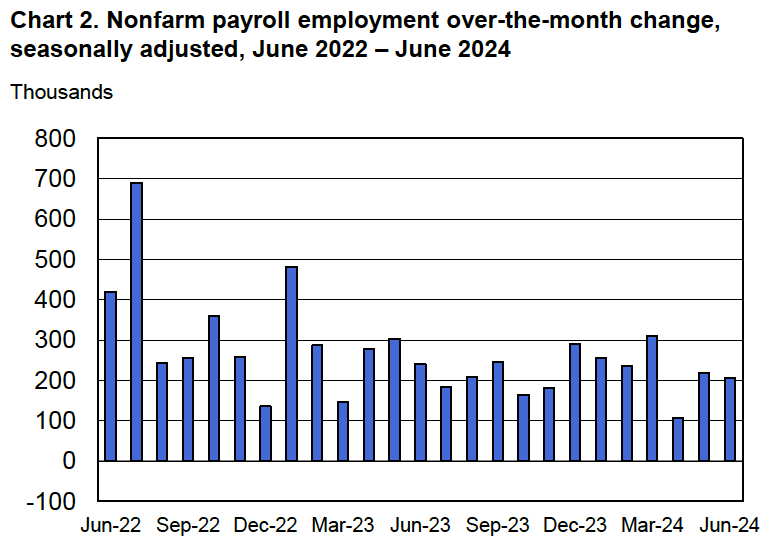

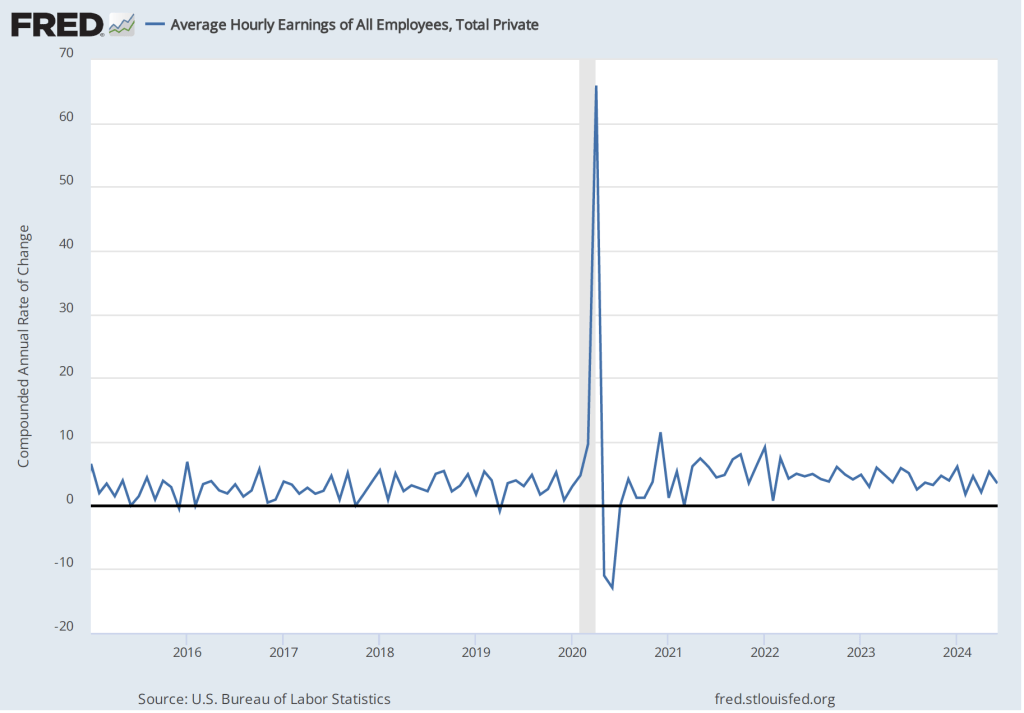

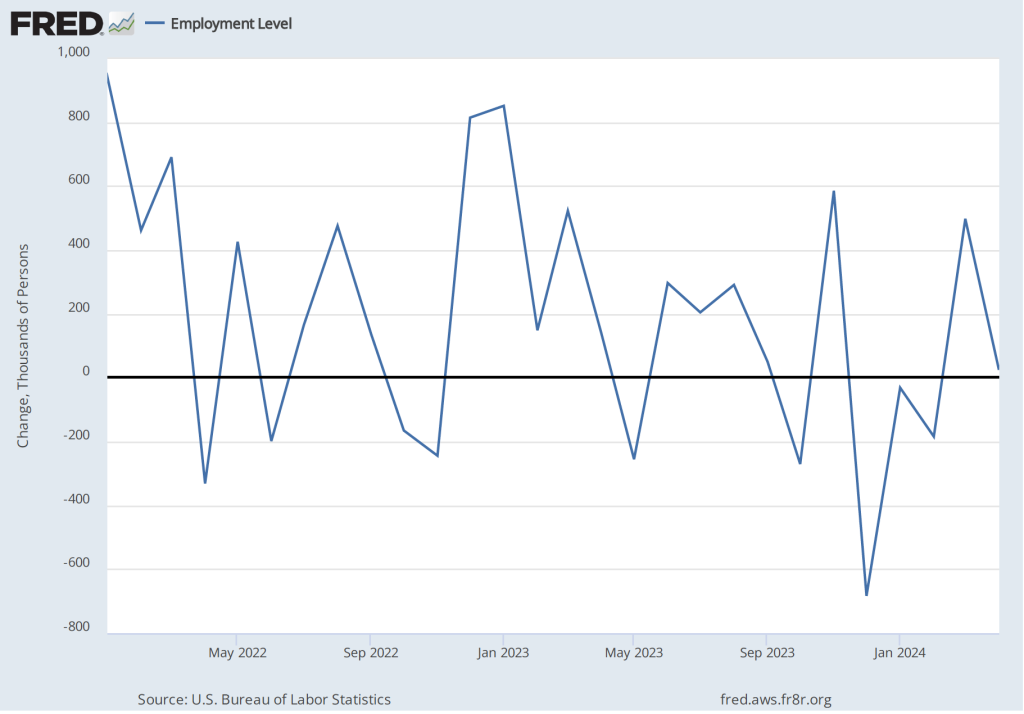

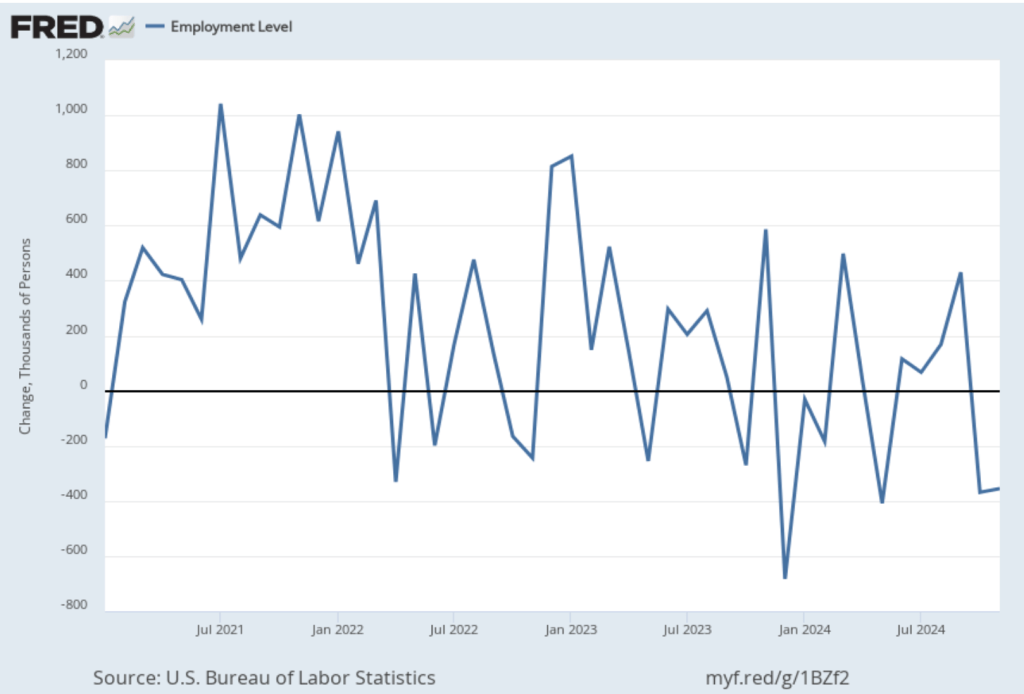

As the following figure shows, the net change in jobs from the household survey moves much more erratically than does the net change in jobs from the establishment survey. The net change in jobs as measured by the household survey for November was a decline of 355,000 jobs following a decline of 368,000 jobs in October. So, the story told by the two surveys is somewhat at odds, with a solid employment gain in the establishment survey contrasted with a significant employment decline in the household survey. (In this blog post, we discuss the differences between the employment estimates in the household survey and the employment estimates in the establishment survey.)

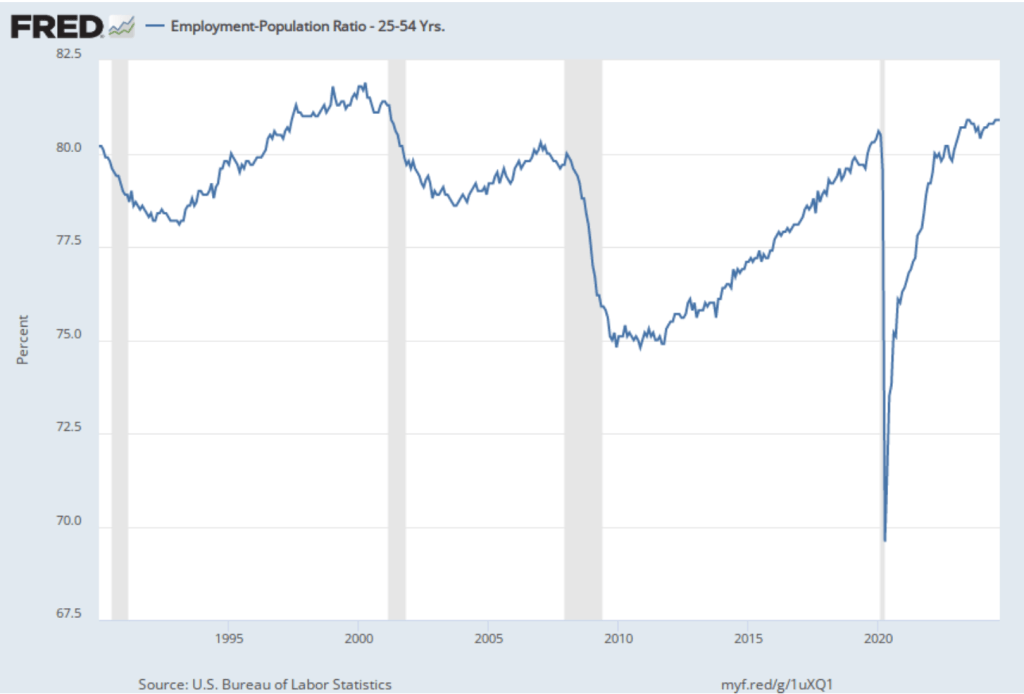

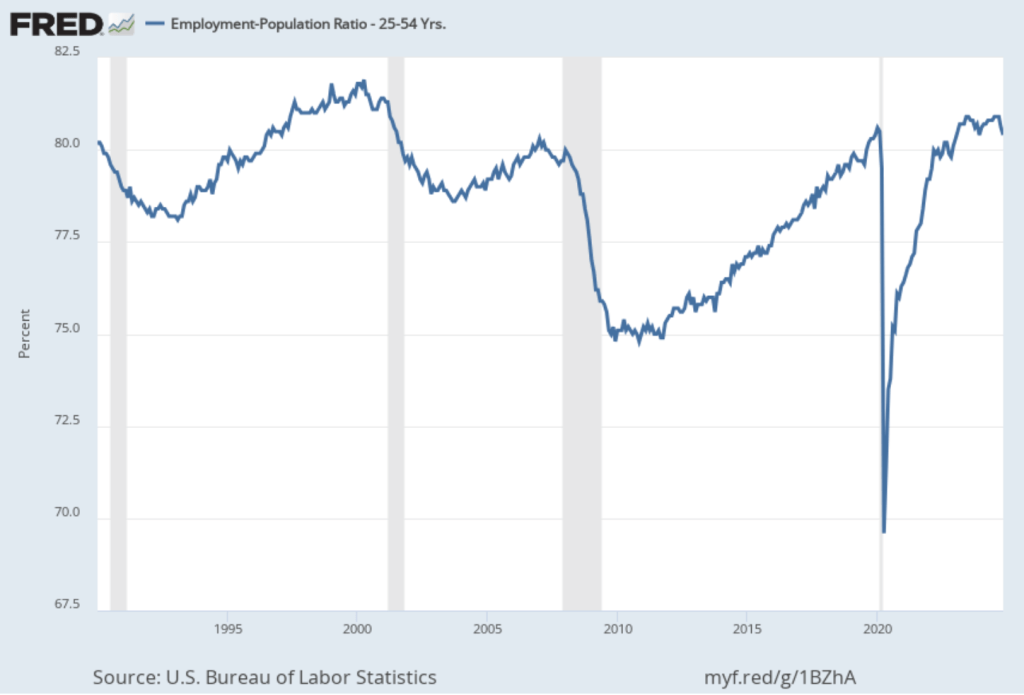

The employment-population ratio for prime age workers—those aged 25 to 54—also declined, as shown in the following figure, to 80.4 percent in November from 80.6 percent in October. Although this was the second consecutive month of decline, the employment-population ratio remained high relative to levels seen since 2001.

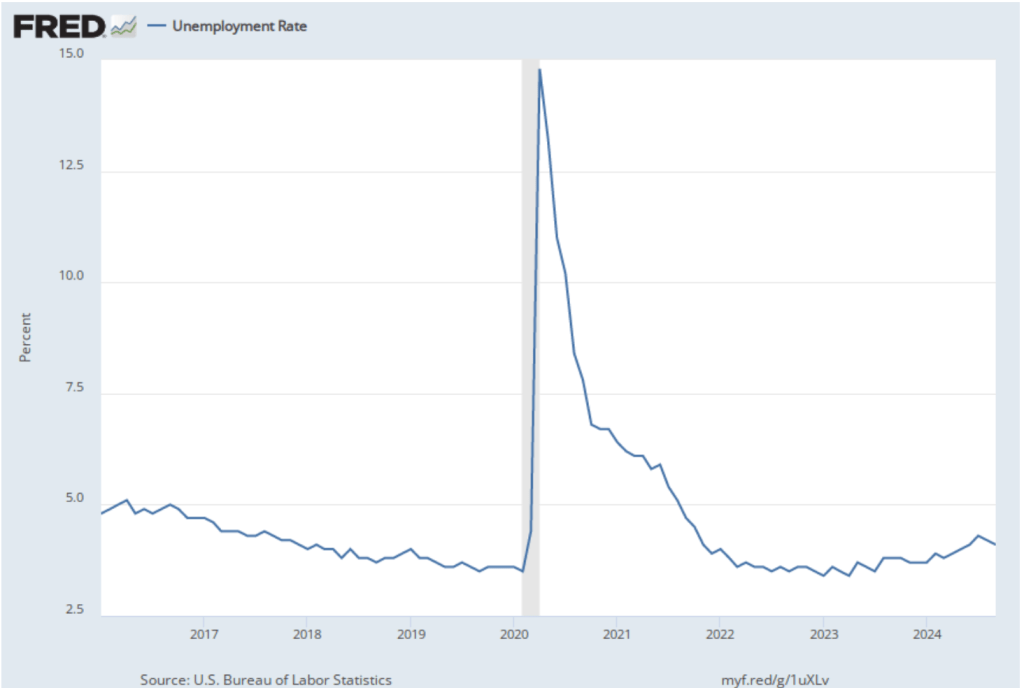

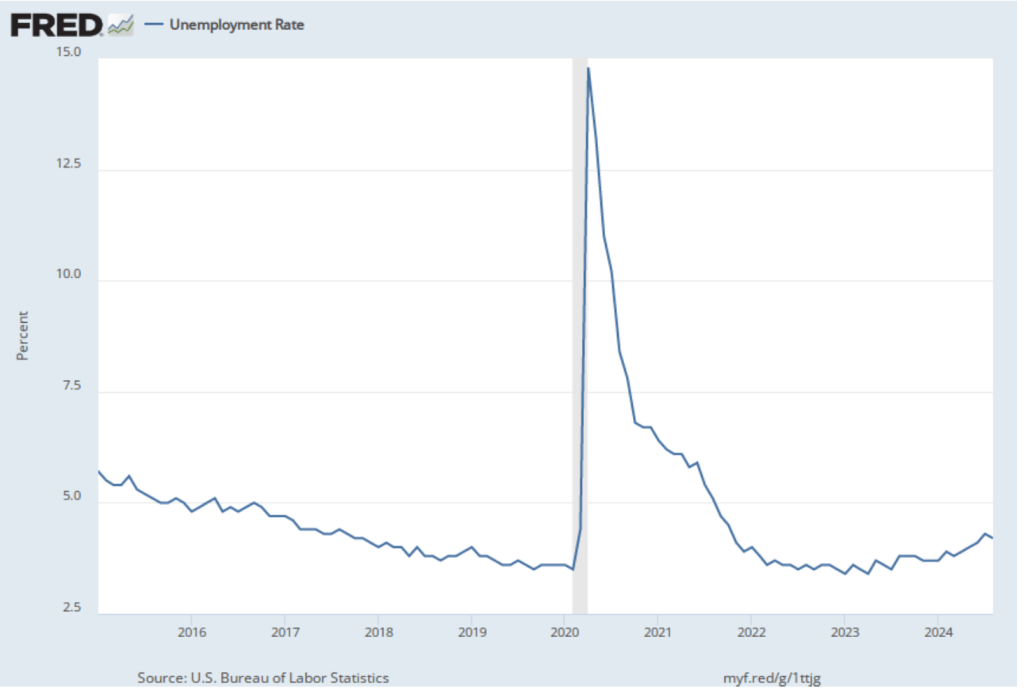

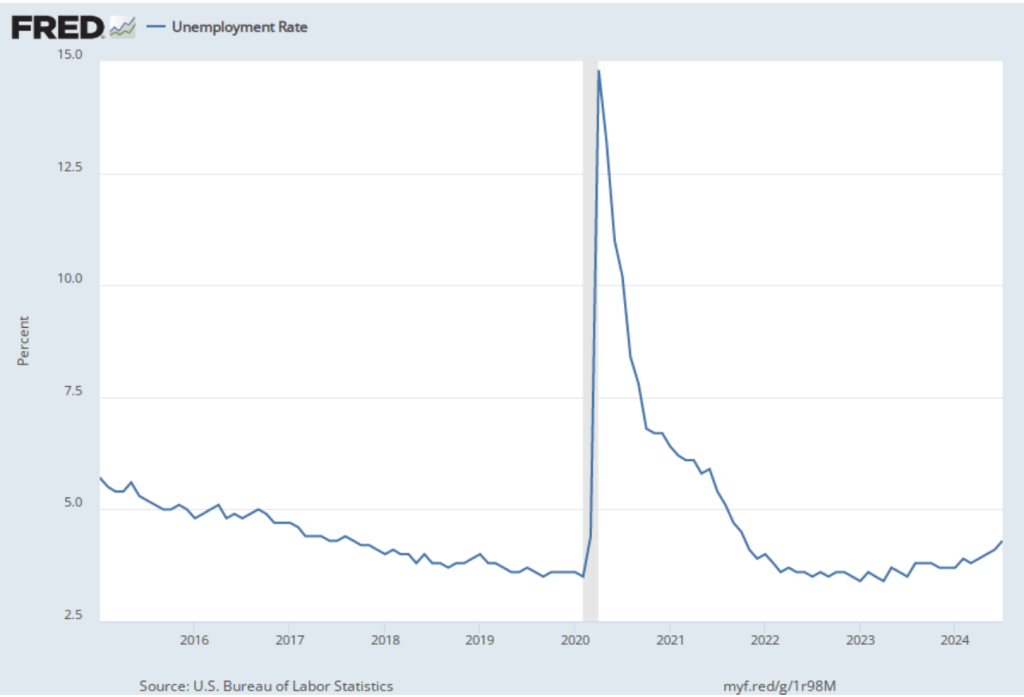

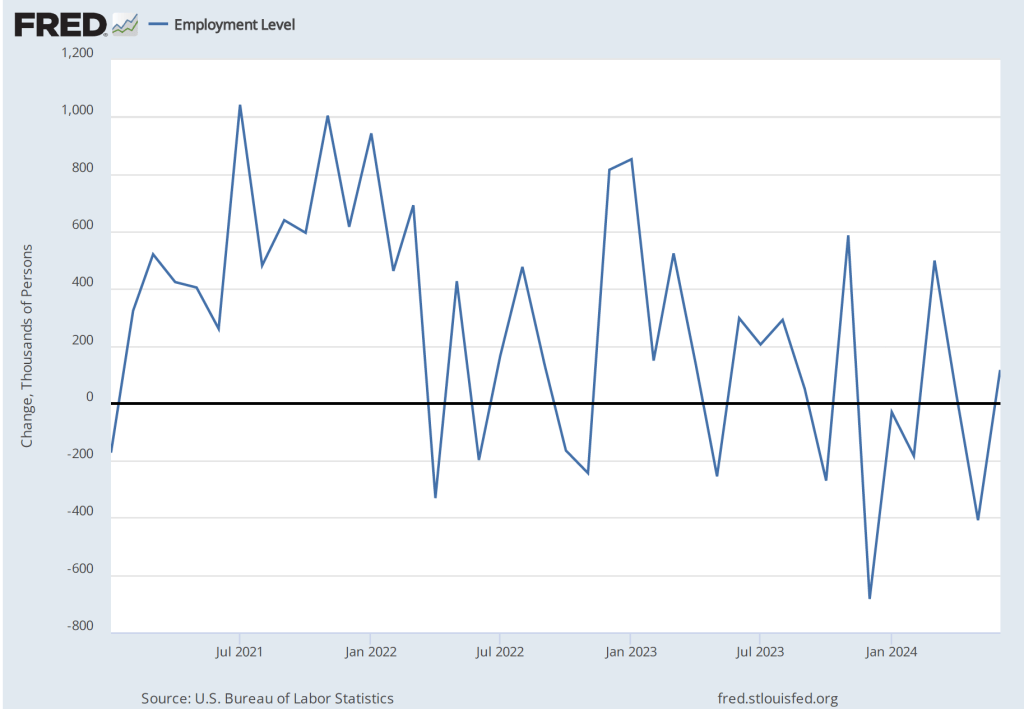

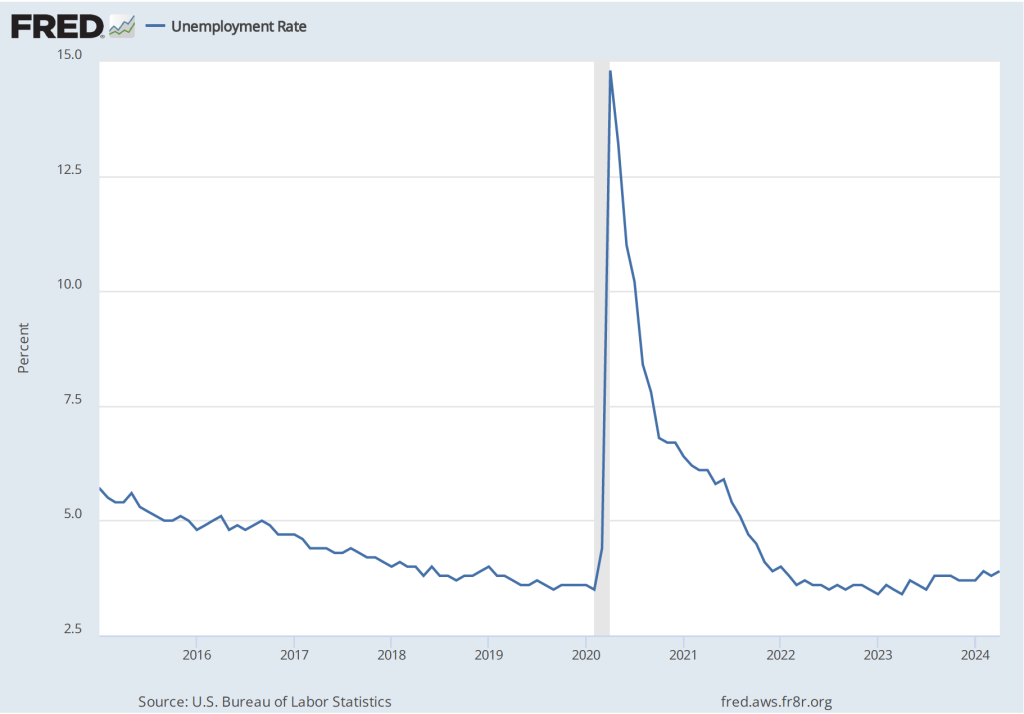

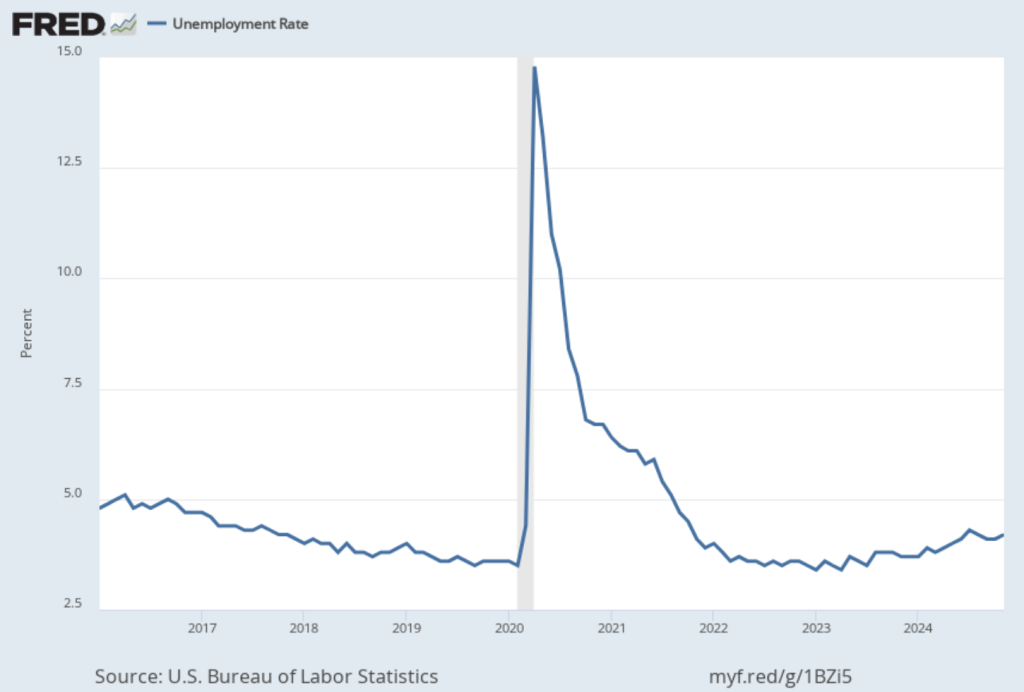

As the following figure shows, the unemployment rate, which is also reported in the household survey, increased slightly to 4.2 percent in November from 4.1 percent in October. The unemployment is still below its recent high of 4.3 percent in July.

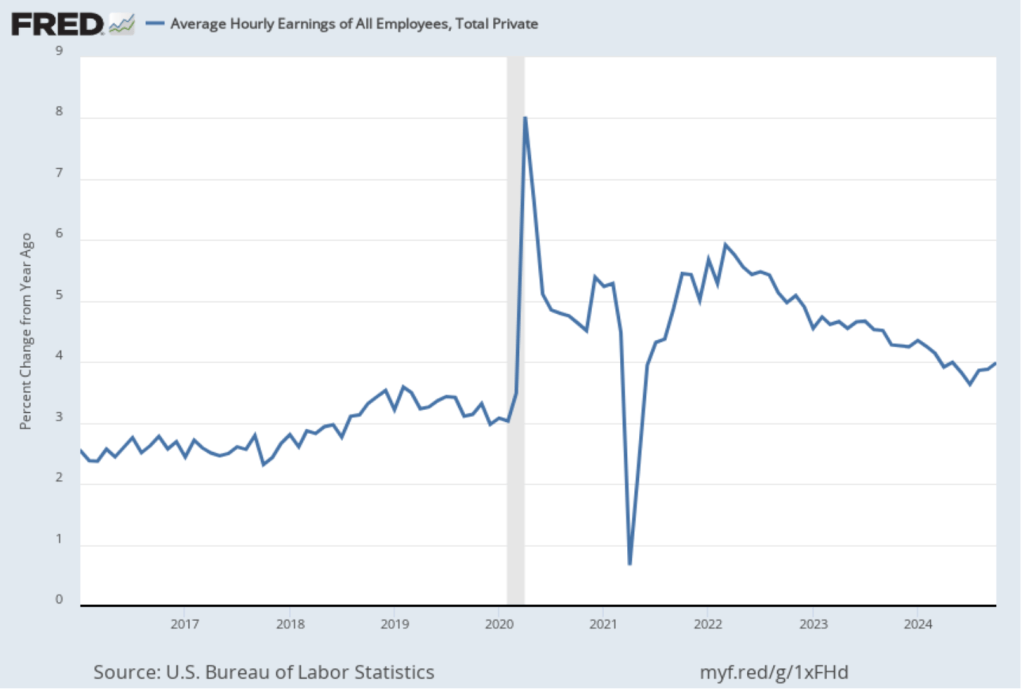

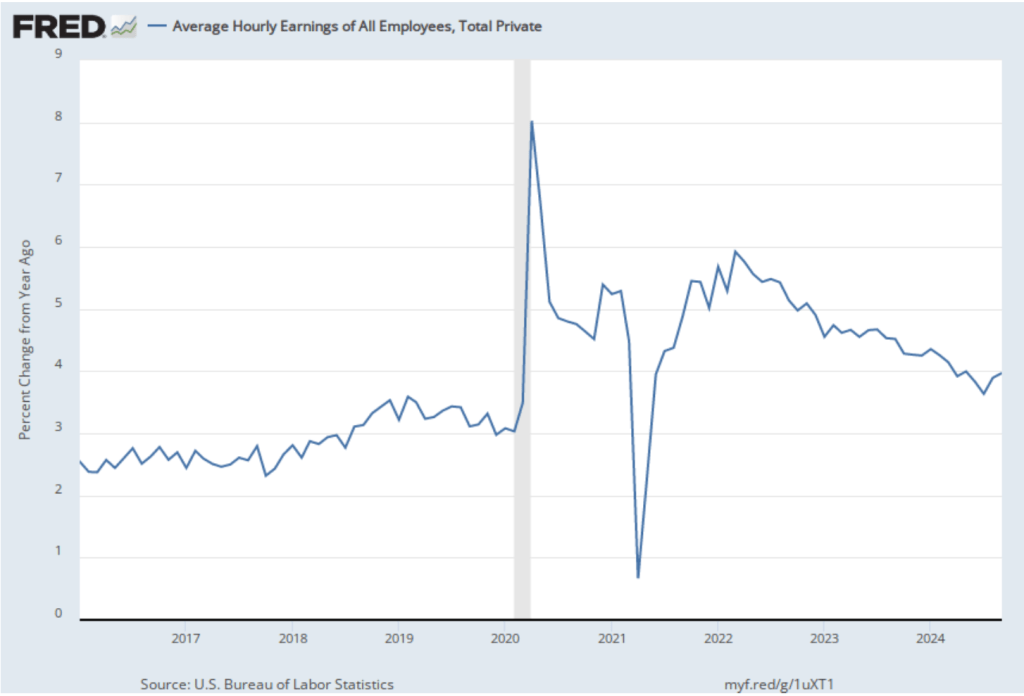

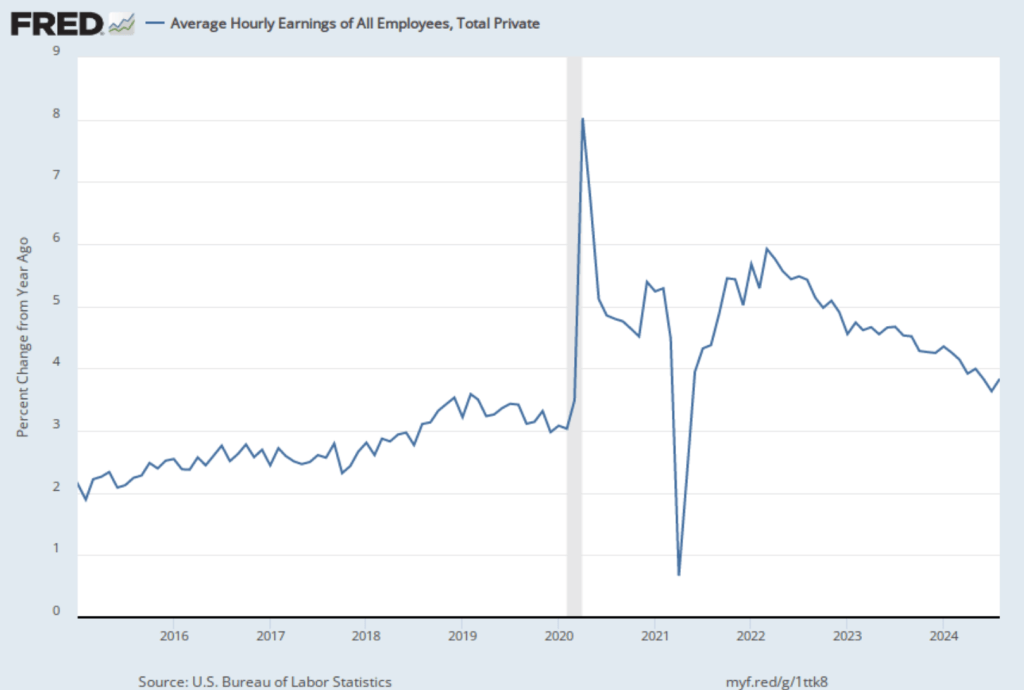

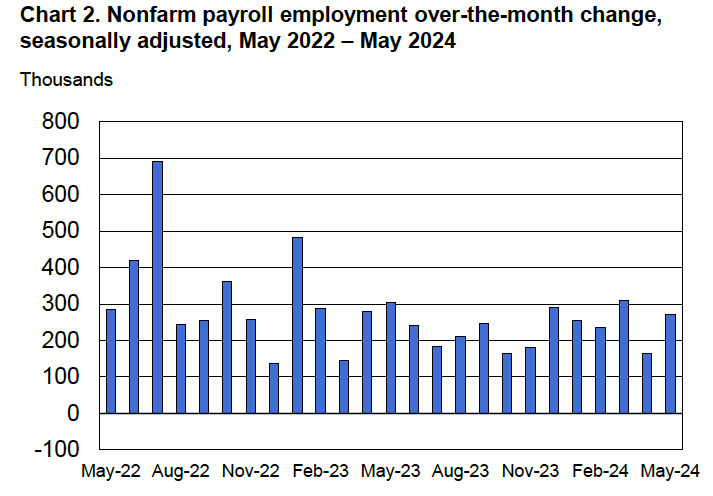

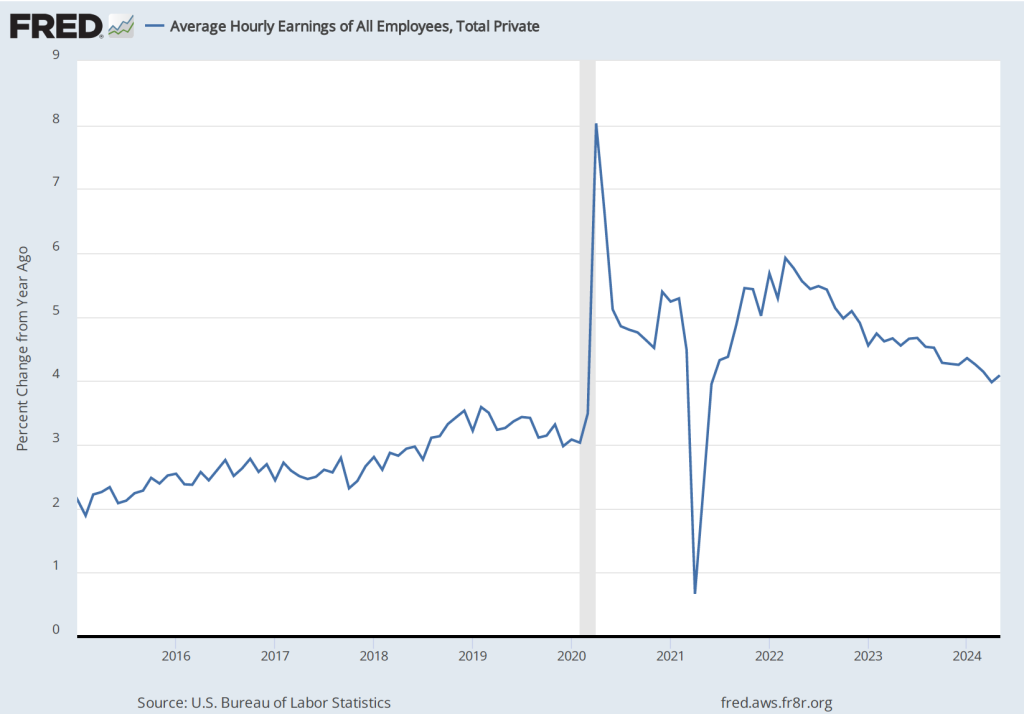

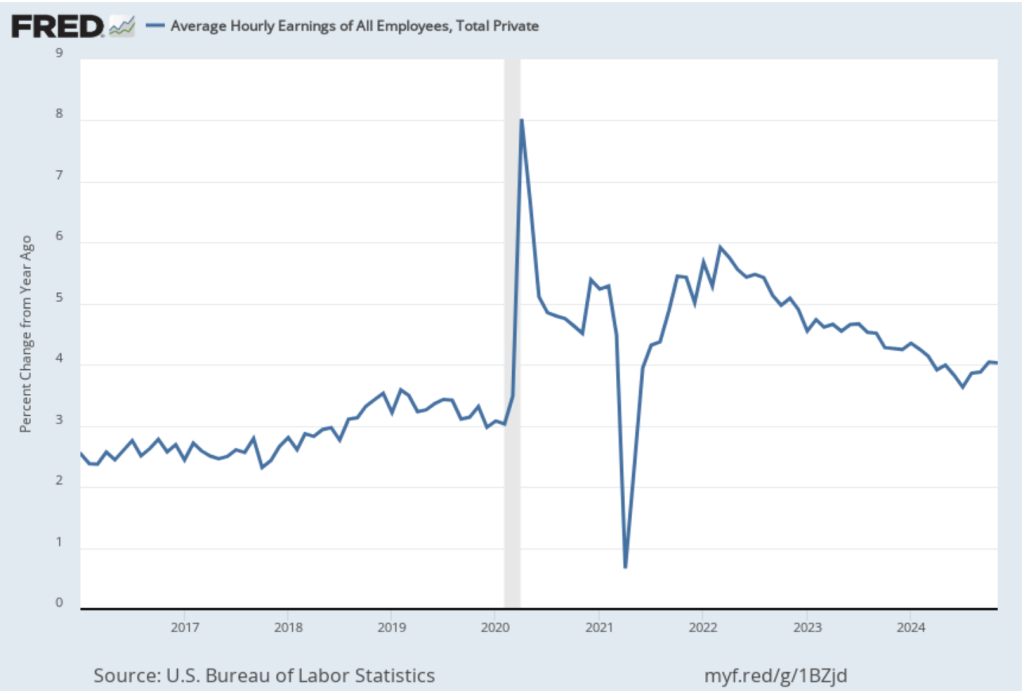

The establishment survey also includes data on average hourly earnings (AHE). As we noted in this post, many economists and policymakers believe the employment cost index (ECI) is a better measure of wage pressures in the economy than is the AHE. The AHE does have the important advantage that it is available monthly, whereas the ECI is only available quarterly. The following figure shows the percentage change in the AHE from the same month in the previous year. The AHE increased 4.0 percent in November, the same as in October.

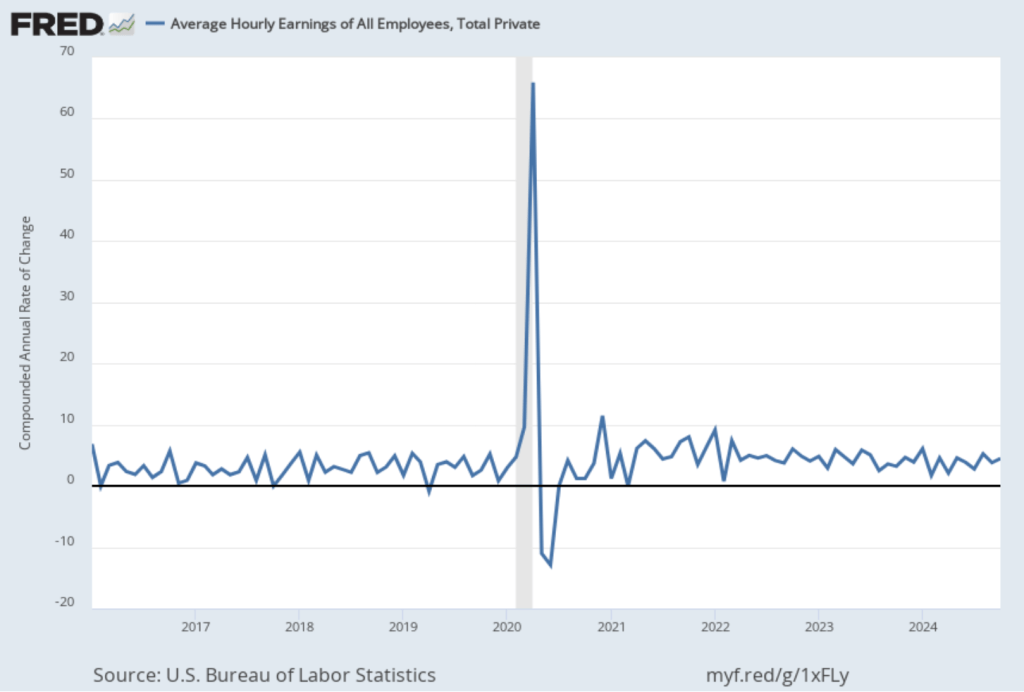

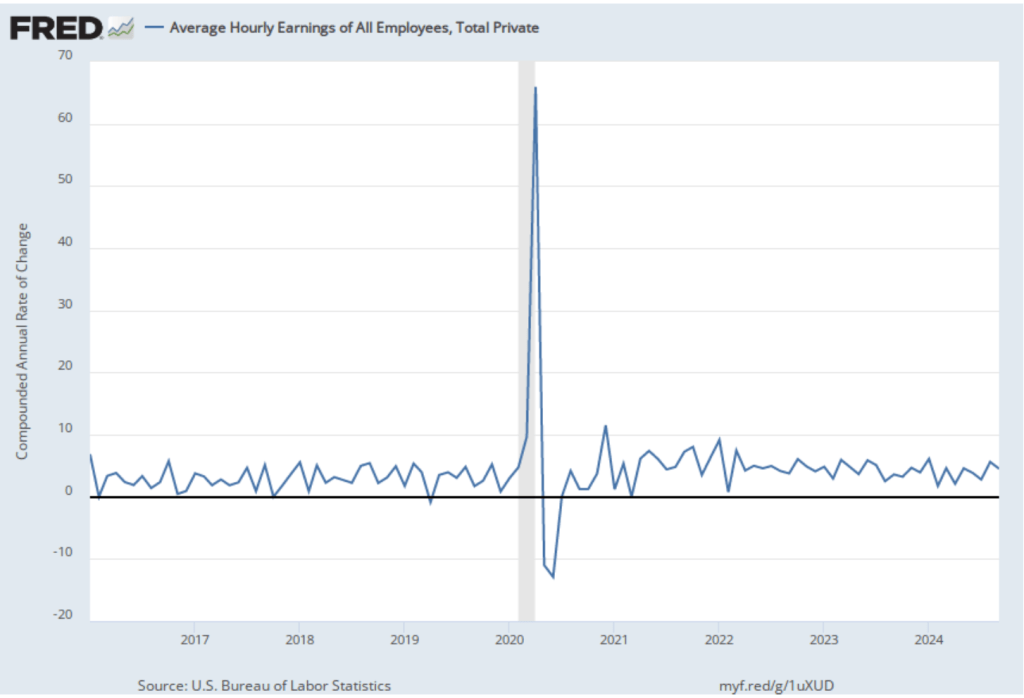

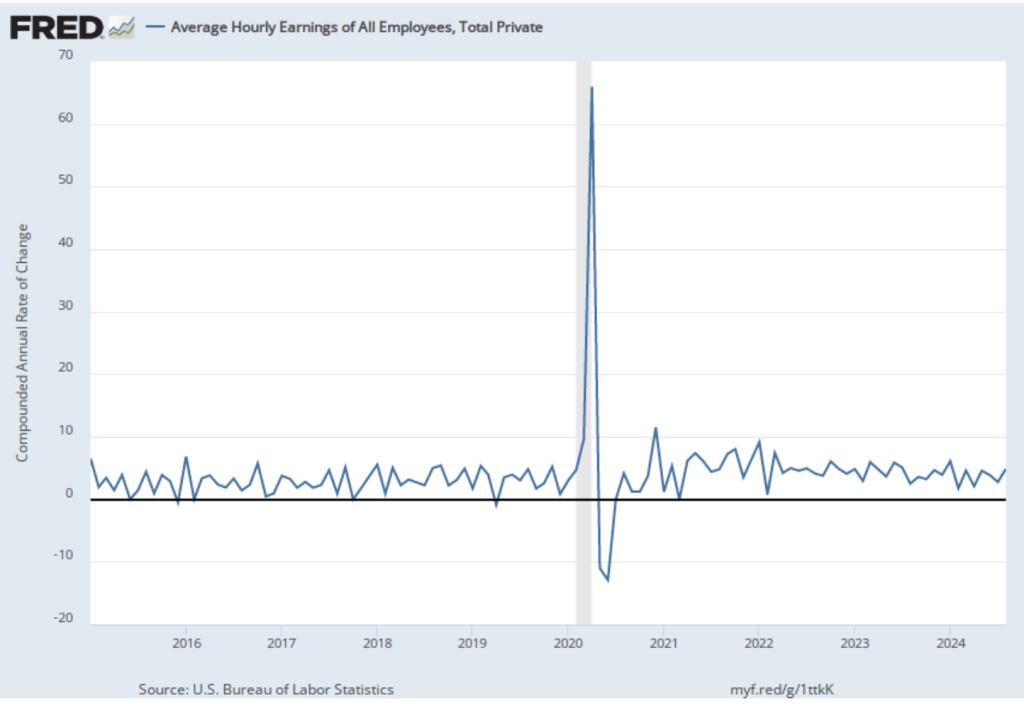

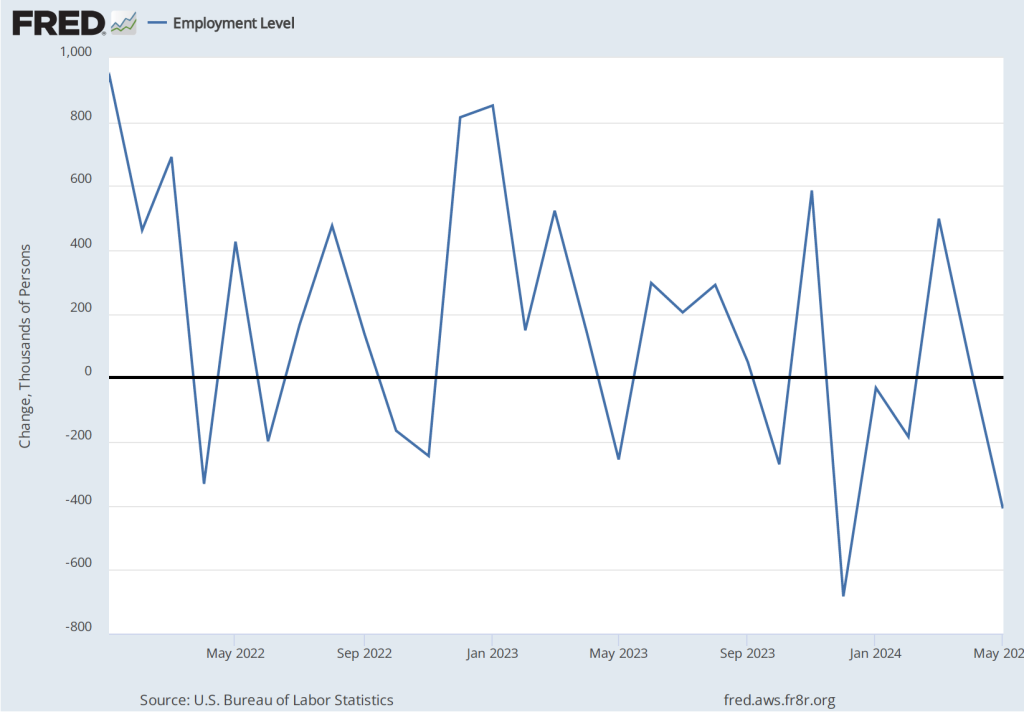

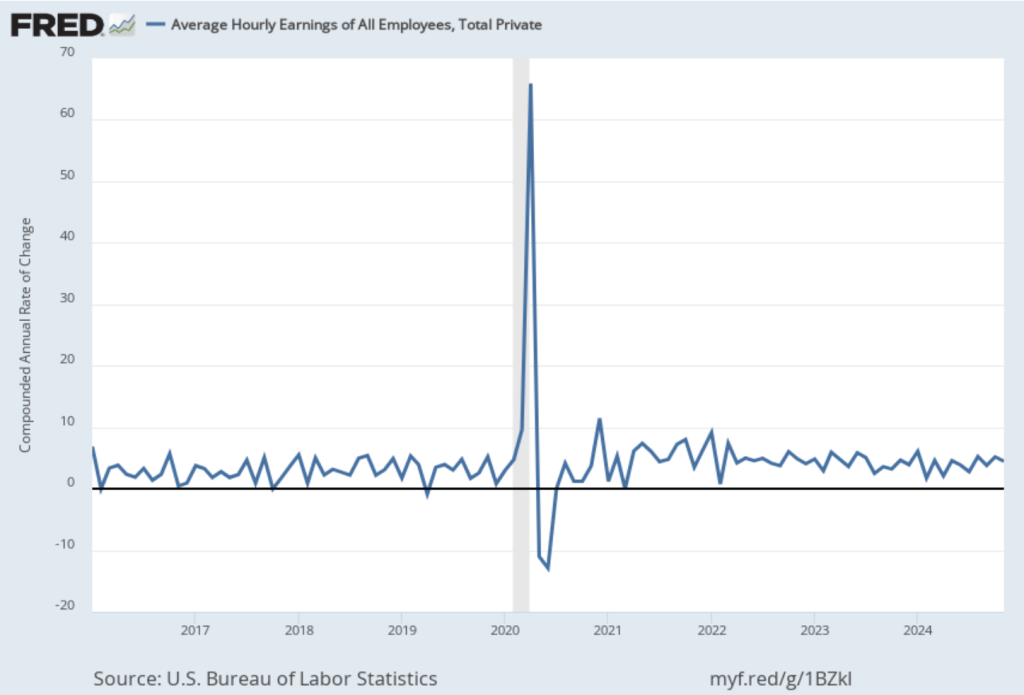

The following figure shows wage inflation calculated by compounding the current month’s rate over an entire year. (The figure above shows what is sometimes called 12-month wage inflation, whereas this figure shows 1-month wage inflation.) One-month wage inflation is much more volatile than 12-month wage inflation—note the very large swings in 1-month wage inflation in April and May 2020 during the business closures caused by the Covid pandemic.

The November 1-month rate of wage inflation was 4.5 percent, a decline from the 5.2 percent rate in October. Whether measured as a 12-month increase or as a 1-month increase, AHE is still increasing more rapidly than is consistent with the Fed achieving its 2 percent target rate of price inflation.

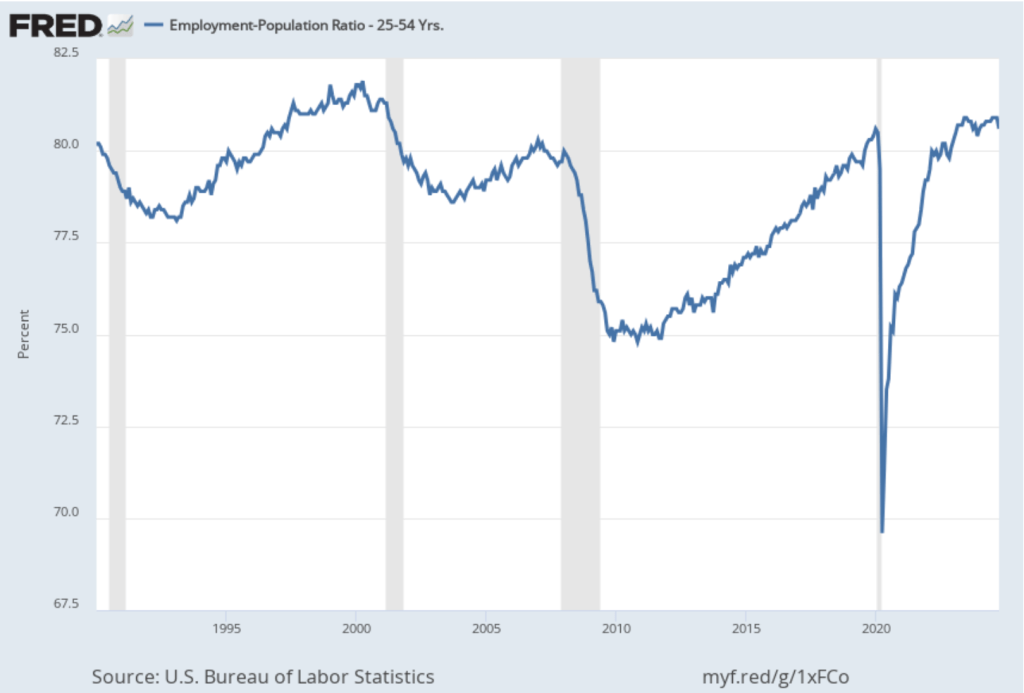

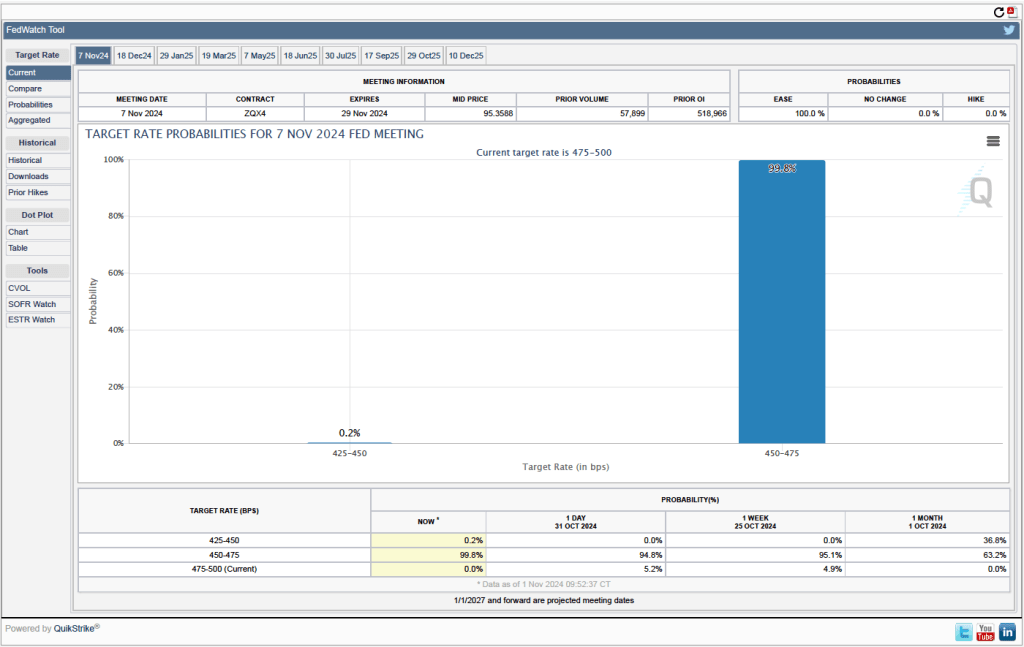

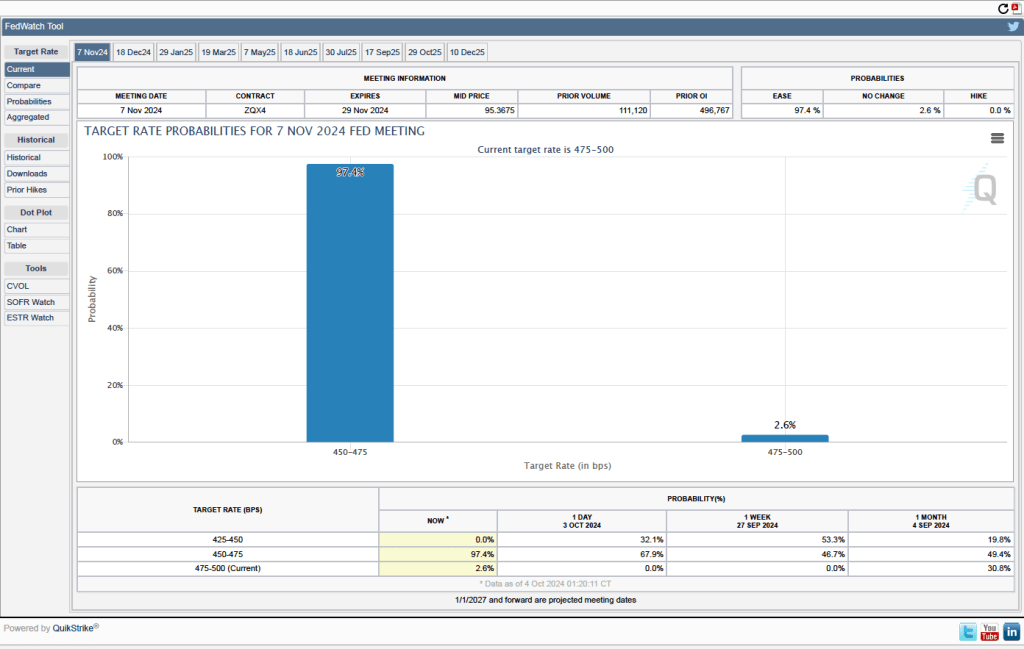

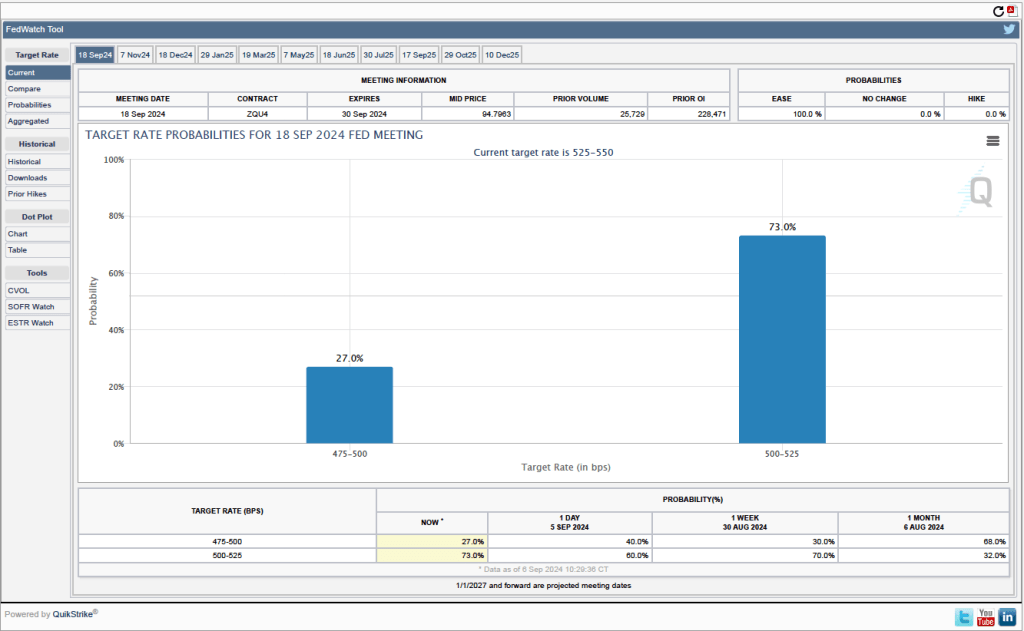

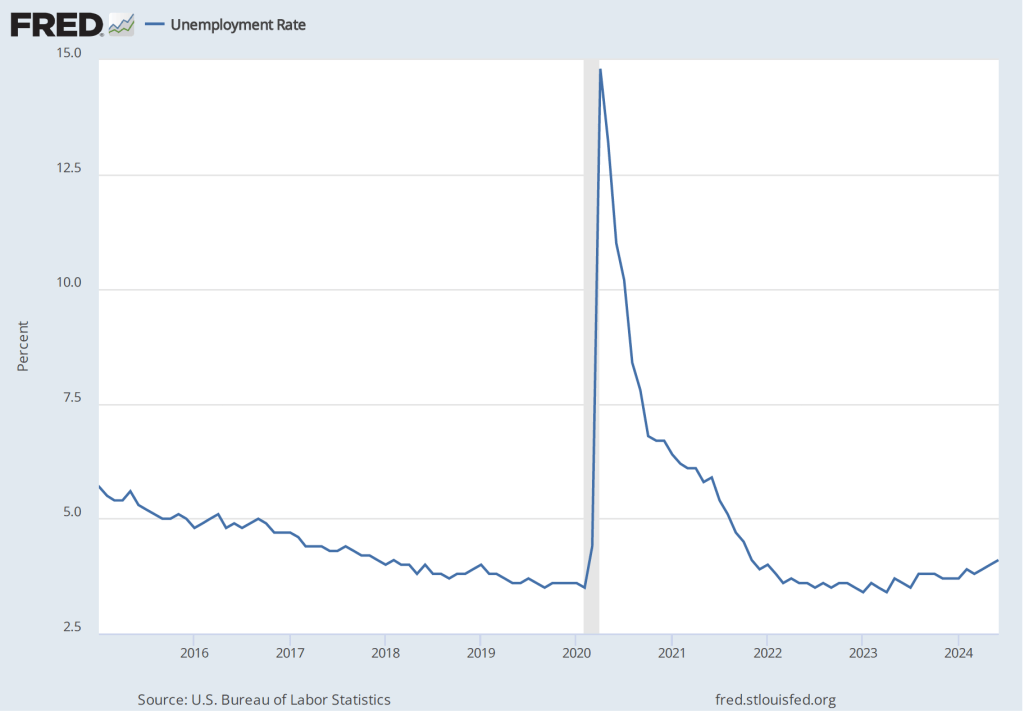

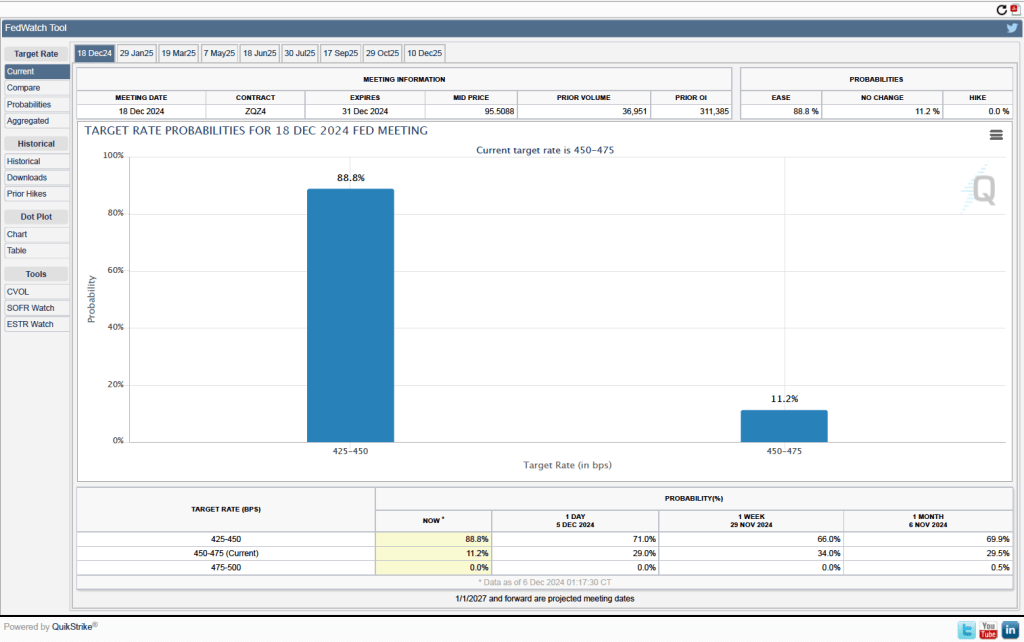

Given these data from the jobs report, is it likely that the FOMC will reduce its target range for the federal funds rate at its next meeting? One indication of expectations of future rate cuts comes from investors who buy and sell federal funds futures contracts. (We discuss the futures market for federal funds in this blog post.) As shown in the following figure, today these investors assign a probability of 88.8 percent to the FOMC cutting its target range for the federal funds rate by 0.25 percentage point (25 basis points) from the current range of 4.50 percent to 4.75 percent, at its next meeting. Investors assign a probability of only 11.2 percent of the committee leaving its target range unchanged.

What do investors expect will happen at the next FOMC meeting after the December 17-18 meeting, which will occur on January 28-29, 2025? As of today, investors assing a probability of only 26.5 percent that the committee will set its target range at 4.00 percent to 4.25 percent, or 50 basis points, below the current target. In other words, only a minority of investors are expecting the committee to cut its target range at both its December and January meetings.