Photo of Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell from federalreserve.gov

Today’s meeting of the Federal Reserve’s policymaking Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) occurred against a backdrop of a shutdown of the federal government that has delayed release of most government economic data. (We discuss the government shutdown here, here, and here.)

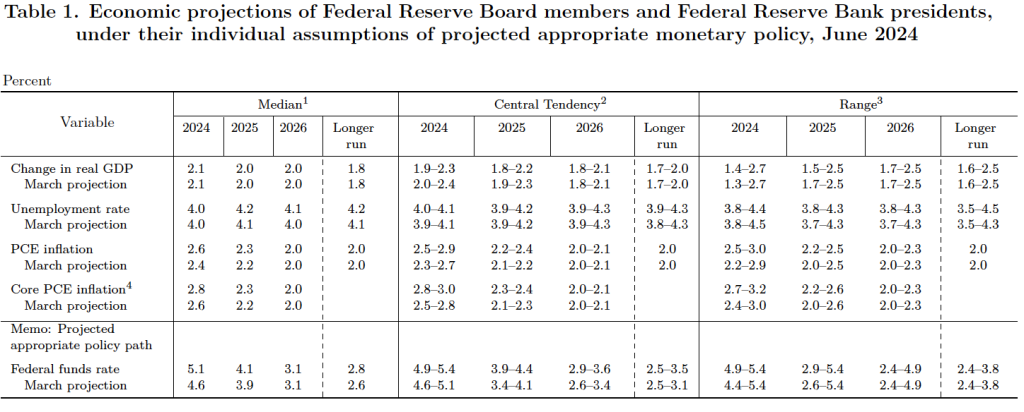

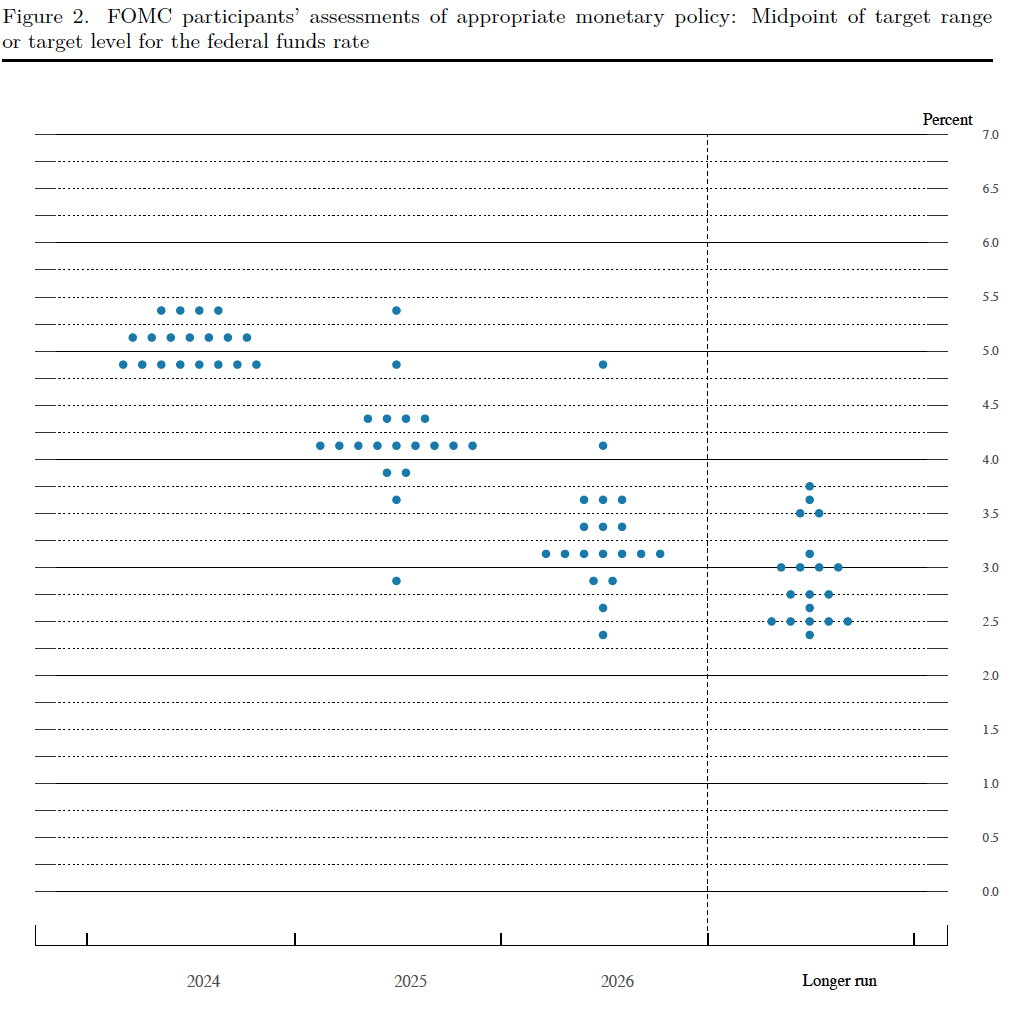

As most observers had expected, the committee decided today to lower its target for the federal funds rate from a range of 4.00 percent to 4.25 percent to a range of 3.75 percent to 4.oo percent—a cut of 0.25 percentage point, or 25 basis points. The members of the committee voted 10 to 2 for the 25 basis point cut with Governor Stephen Miran dissenting because he preferred a 50 basis point cut and Jeffrey Schmid, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, dissenting because he preferred that the target range be left unchanged at this meeting.

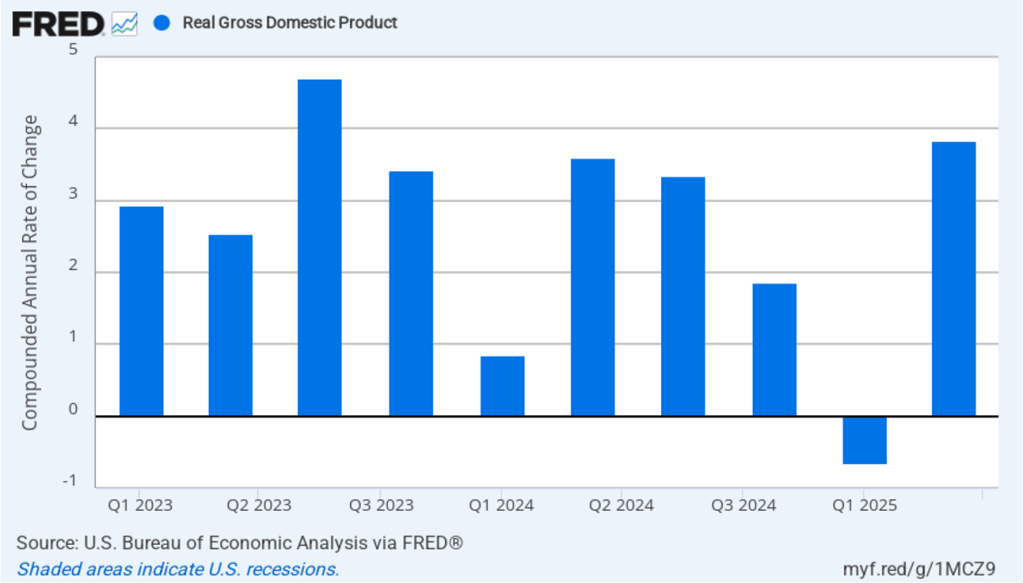

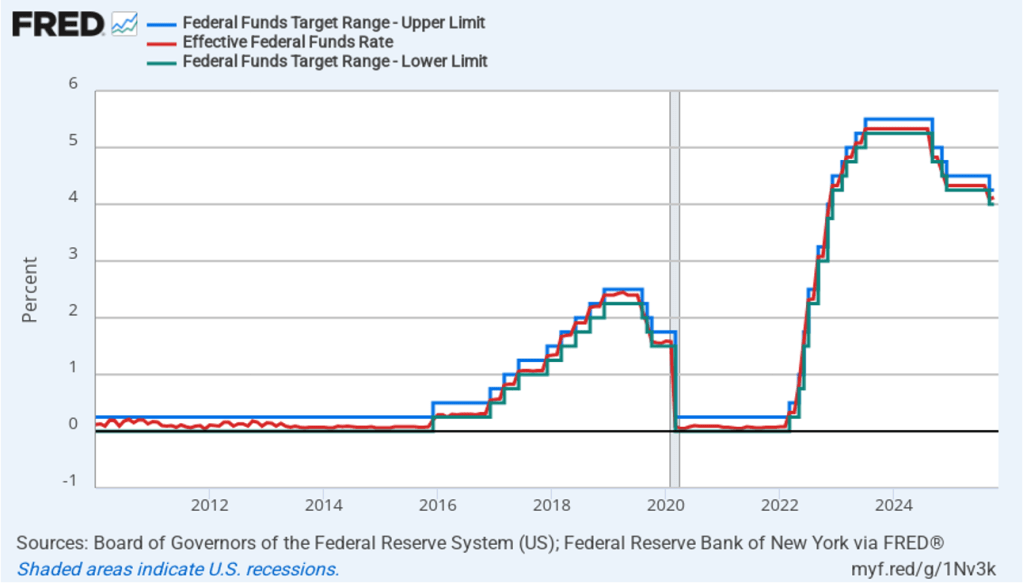

The following figure shows, for the period since January 2010, the upper bound (the blue line) and the lower bound (the green line) for the FOMC’s target range for the federal funds rate, as well as the actual values of the federal funds rate (the red line). Note that the Fed has been successful in keeping the value of the federal funds rate in its target range. (We discuss the monetary policy tools the FOMC uses to maintain the federal funds rate in its target range in Macroeconomics, Chapter 15, Section 15.2 (Economics, Chapter 25, Section 25.2).)

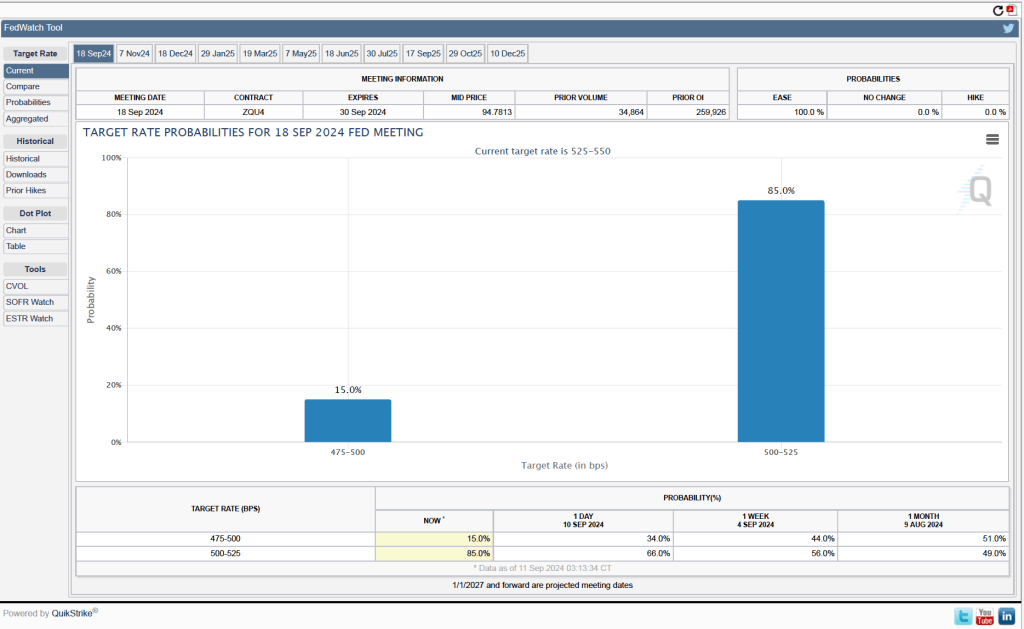

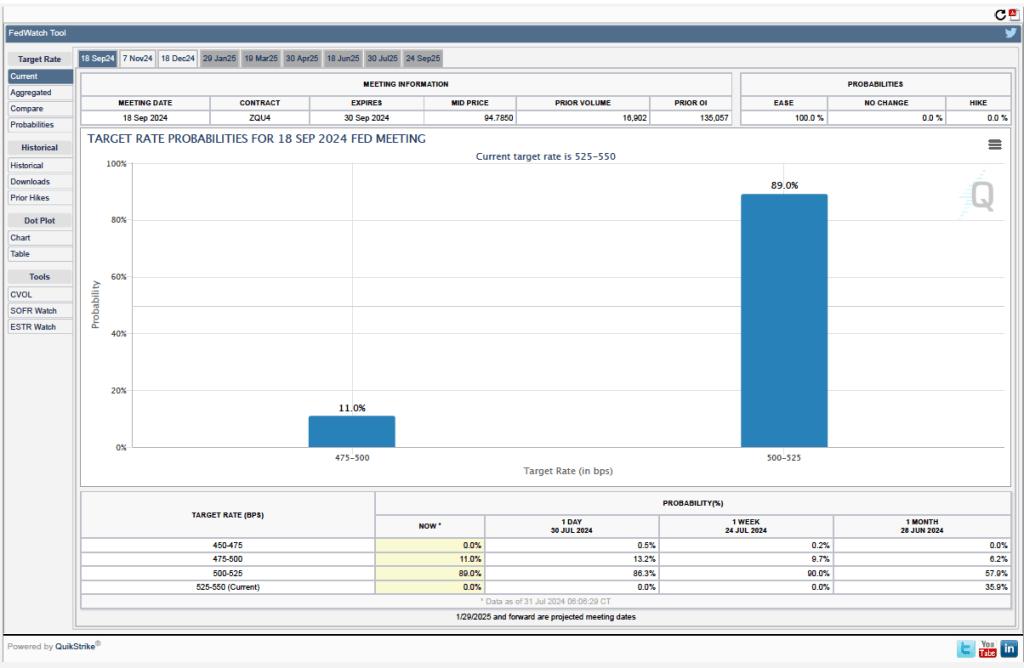

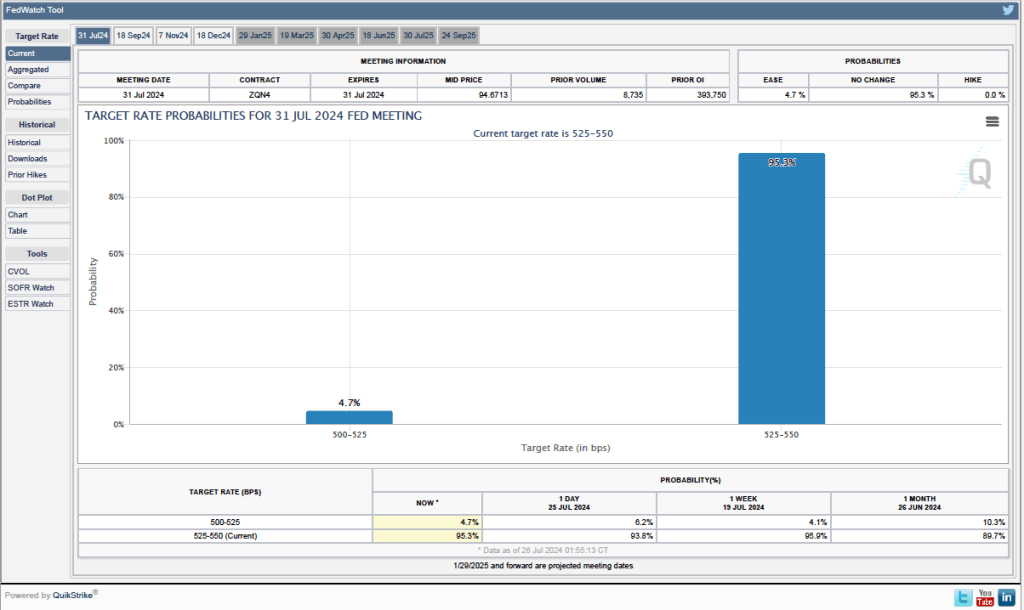

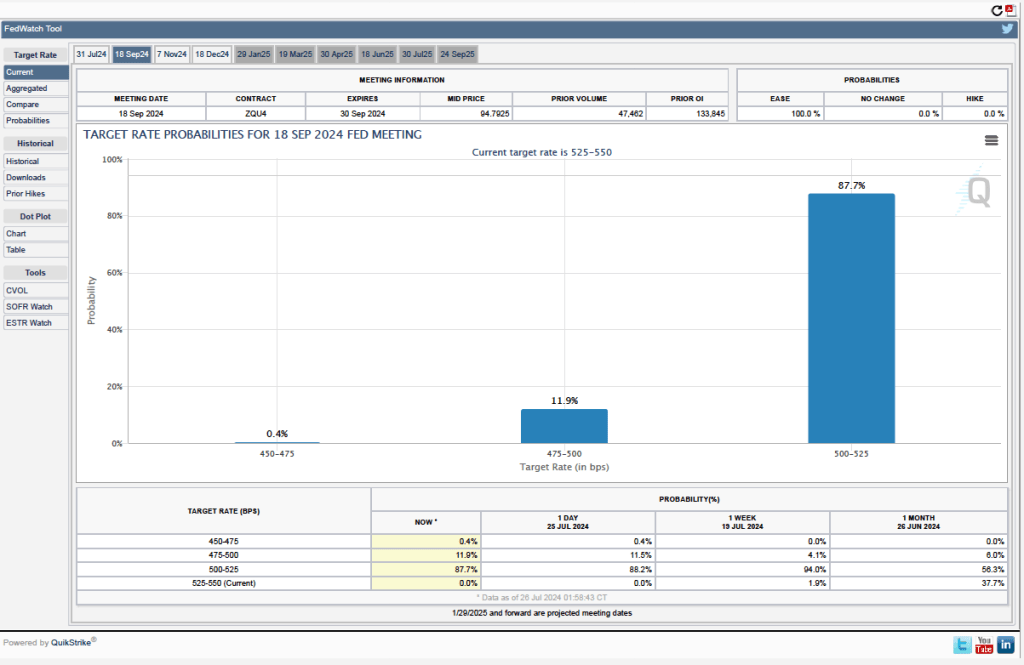

During his press conference following the meeting, Fed Chair Jerome Powell made news by stating that a further cut in the target rate at the FOMC’s meeting on December 9–10 is not a foregone conclusion. This statement came as a surprise to investors who buy and sell federal funds futures contracts. (We discuss the futures market for federal funds in this blog post.) As of yesterday, investors has assigned a probability of 90.5 percent to the committee cutting its target range by another 25 basis points at the December meeting. Today that probability dropped to zero. Instead investors now assign a probability of 67.8 percent to the target remaining unchanged at that meeting, and a probability of 32.2 percent of the committee raising its target by 25 basis points.

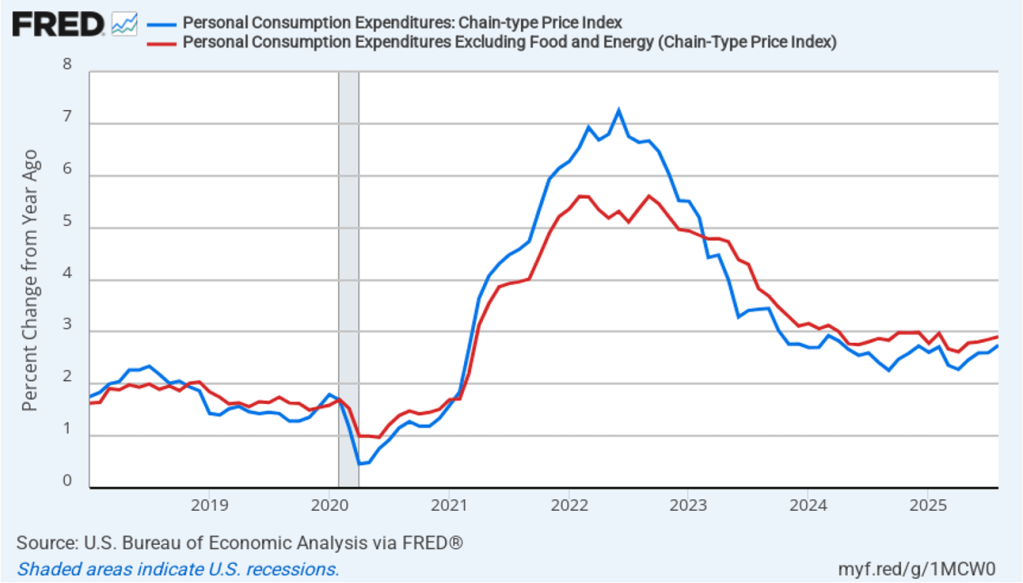

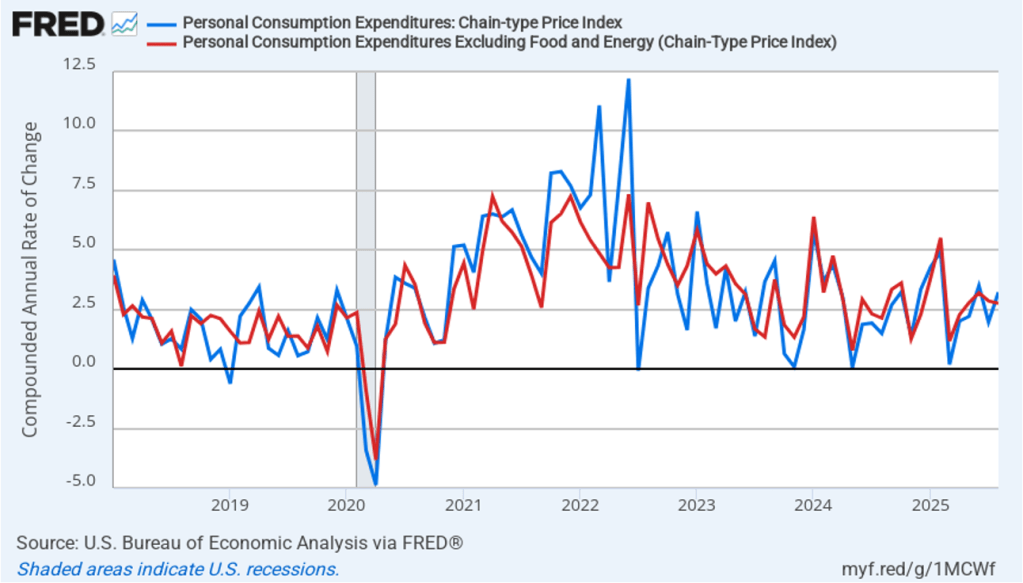

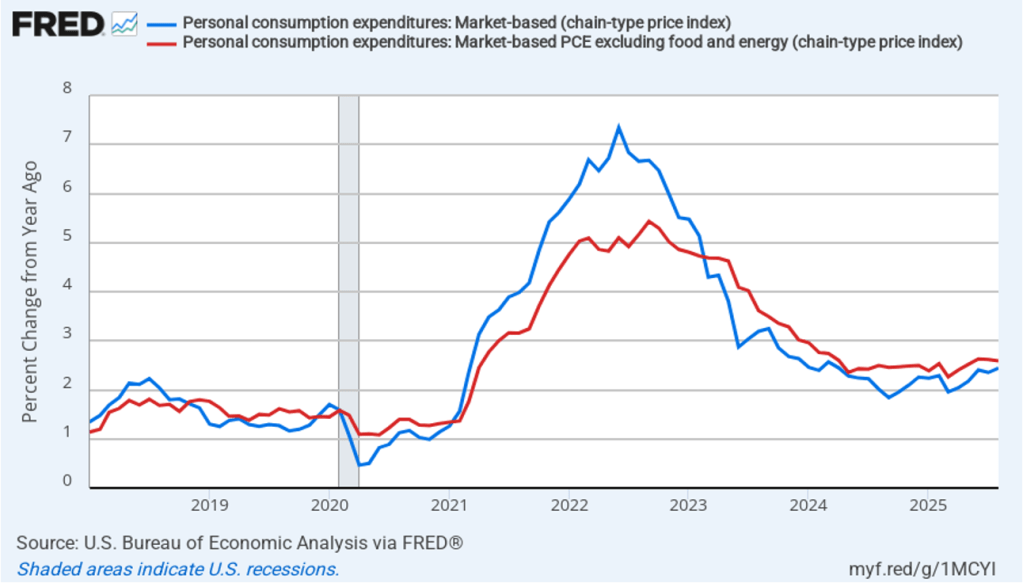

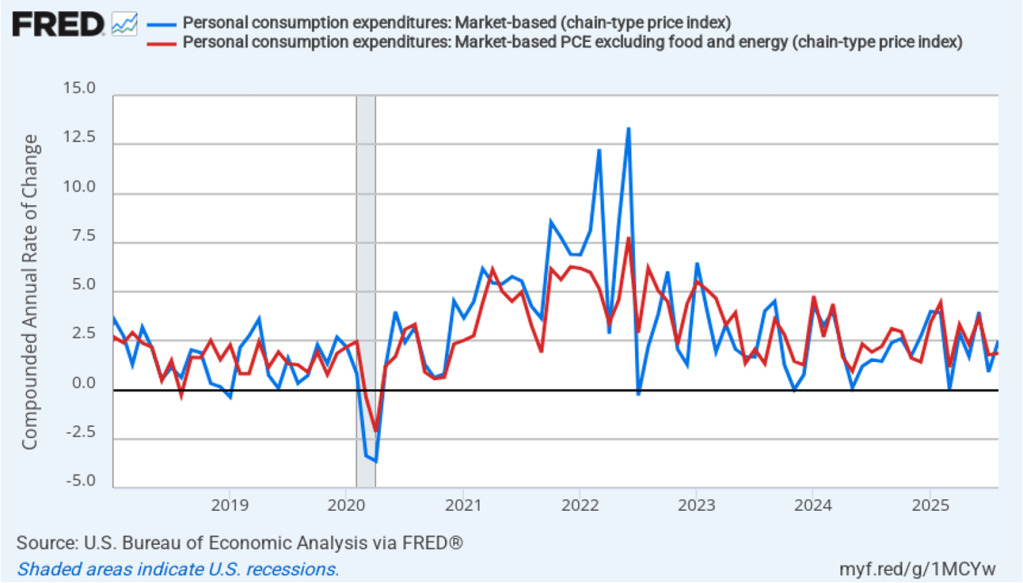

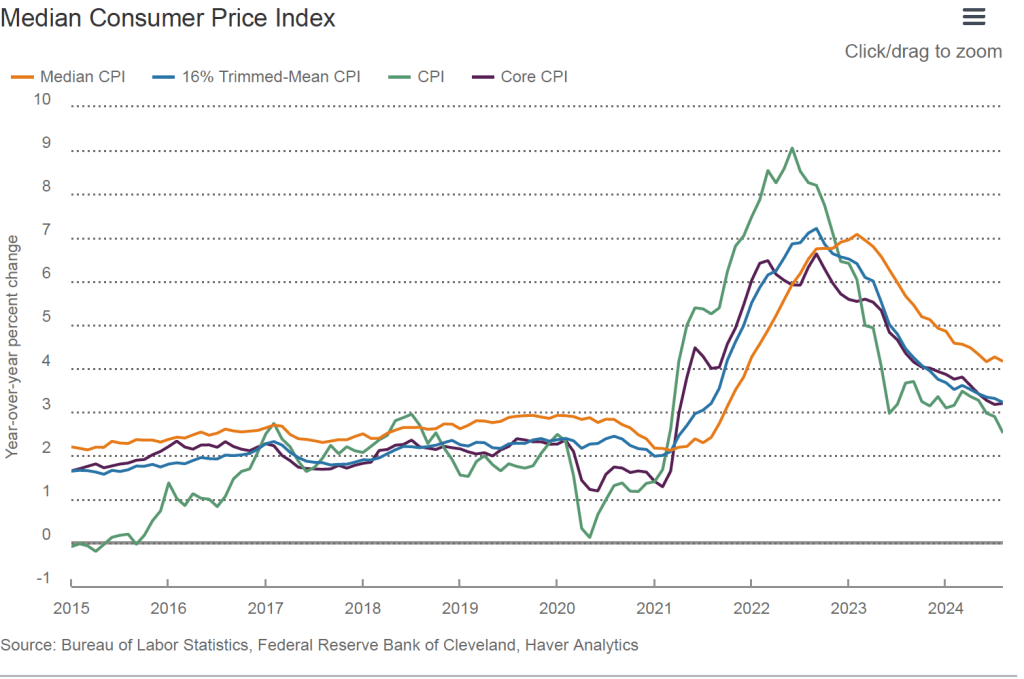

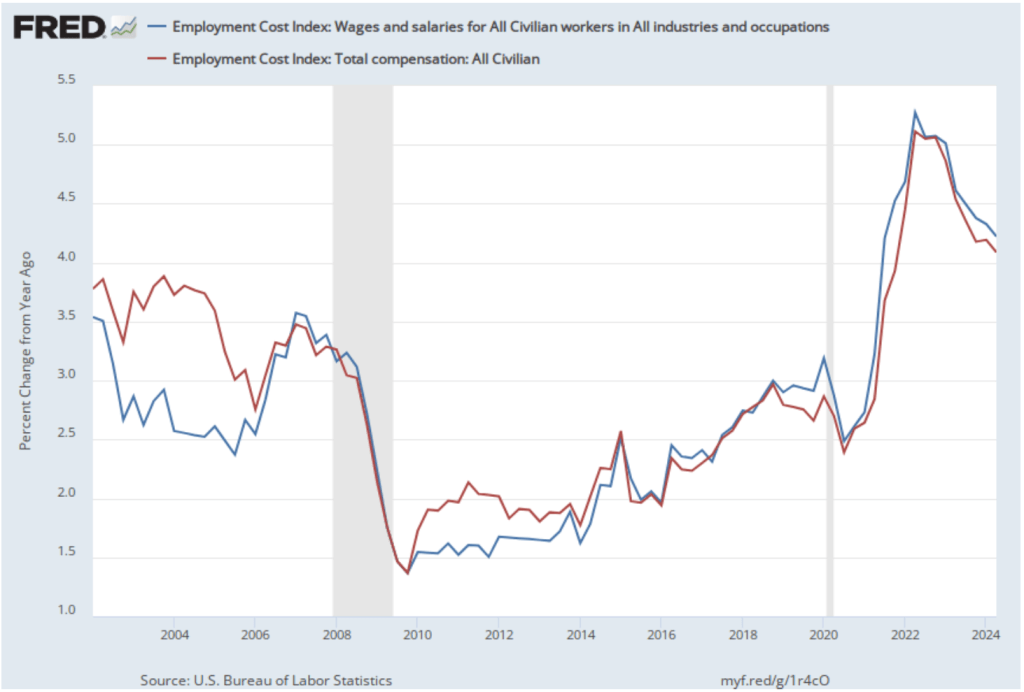

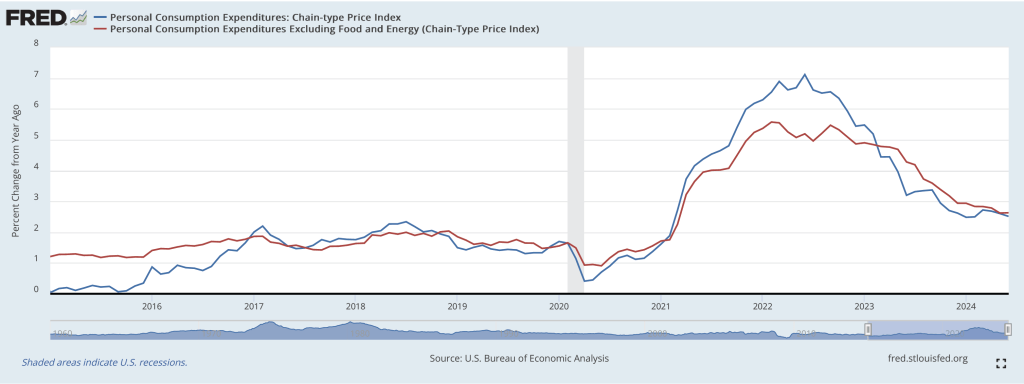

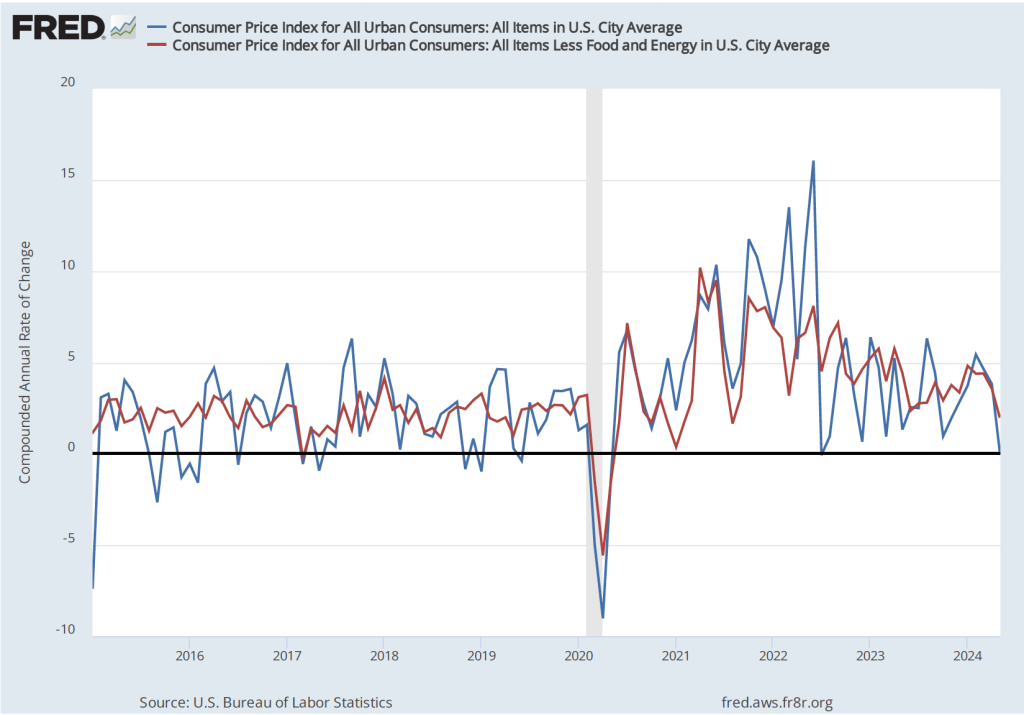

Powell also indicated that he believes that the recent increase in inflation was largely due to the effects of the increase in tariff rates that the Trump administration began implementing in April. (We discuss the recent data on inflation in this post.) Powell indicated that committee members expect that the tariff increases will cause a one-time increase in the price level, rather than a long-term increase in the inflation rate. As a result, he said that the shift in the “balance of risks” caused the committee to believe that cutting the target for the federal funds rate was warranted to avoid the possibility of a significant rise in the unemployment rate.

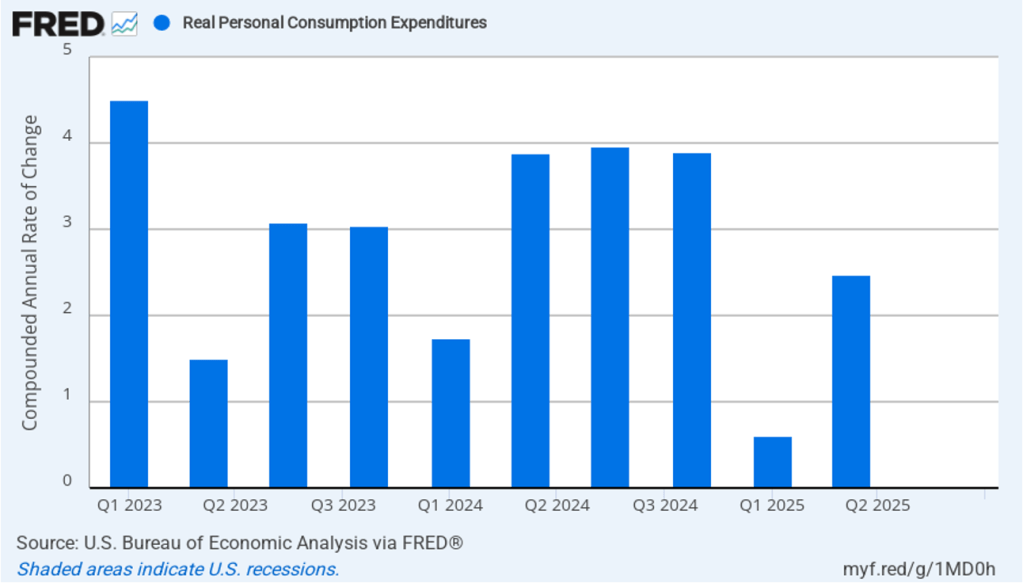

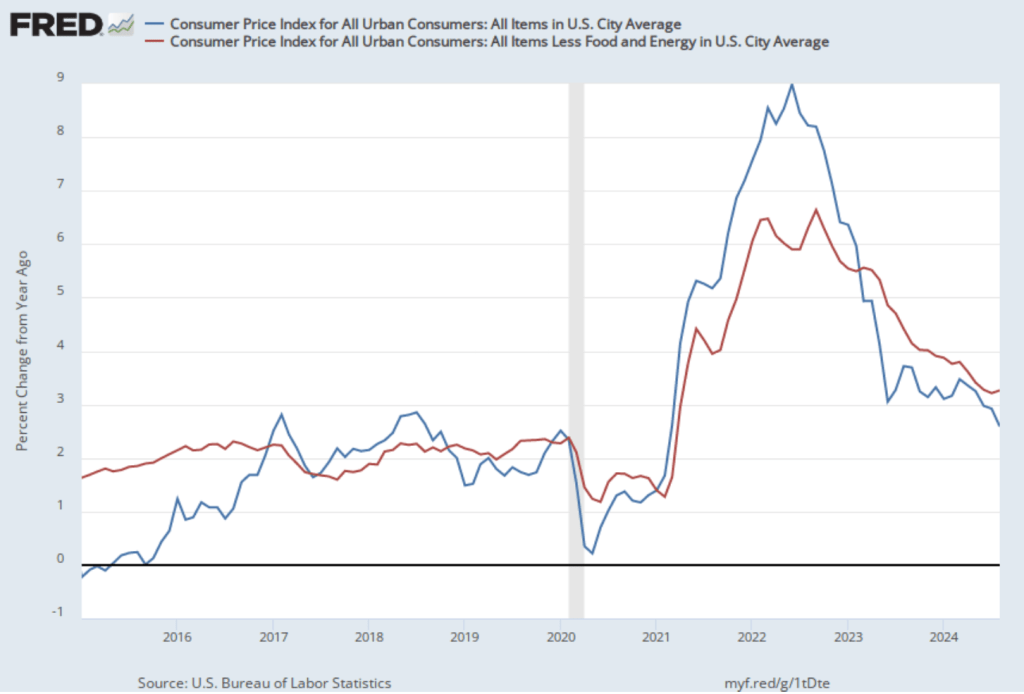

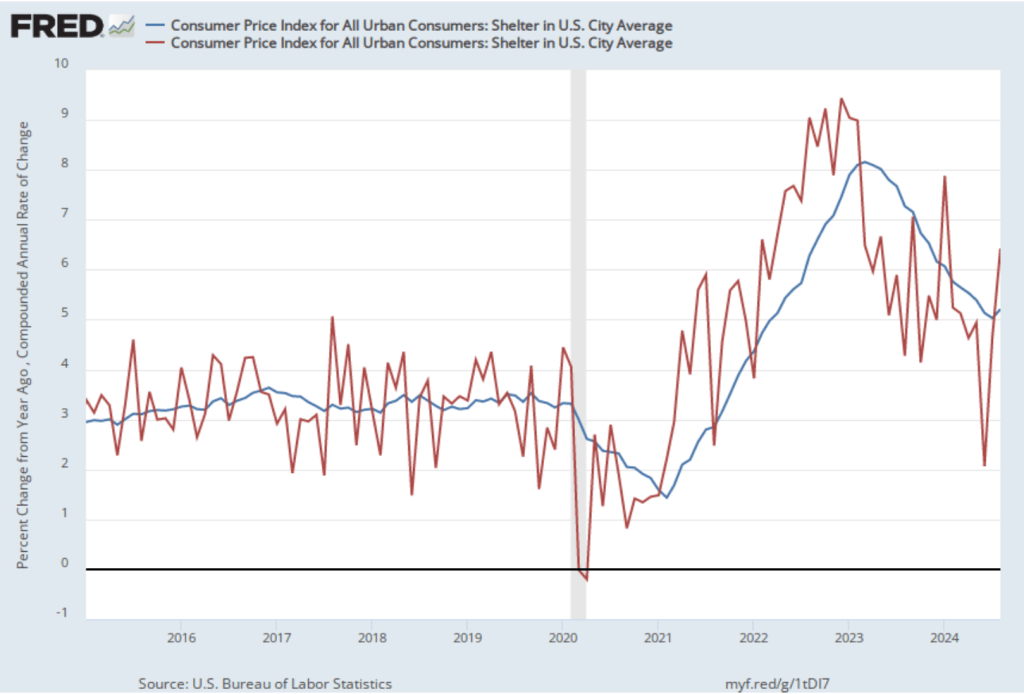

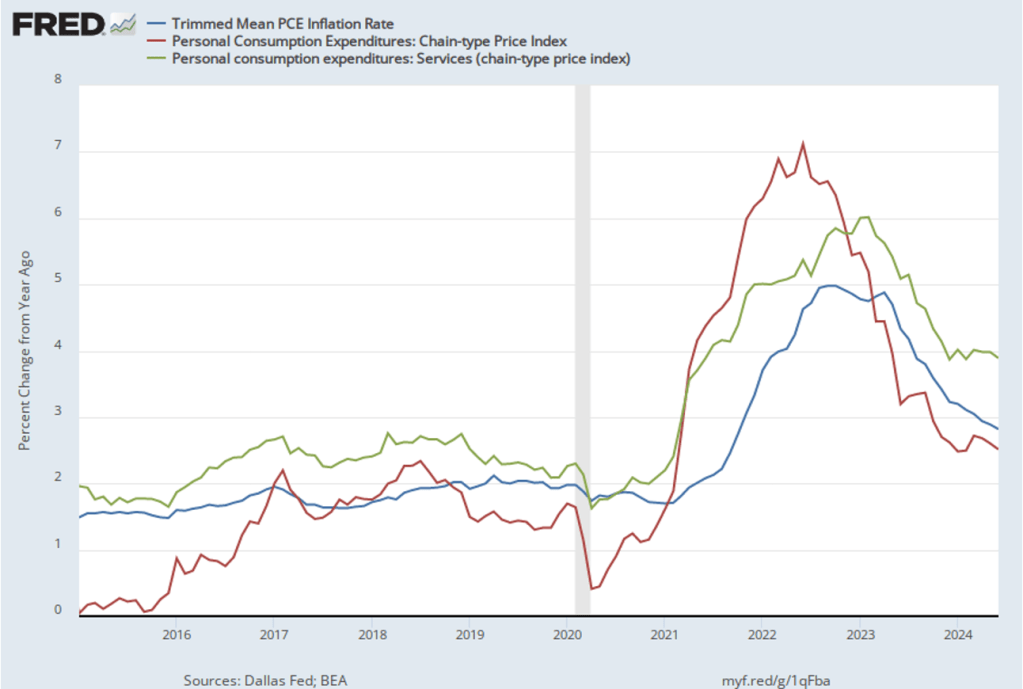

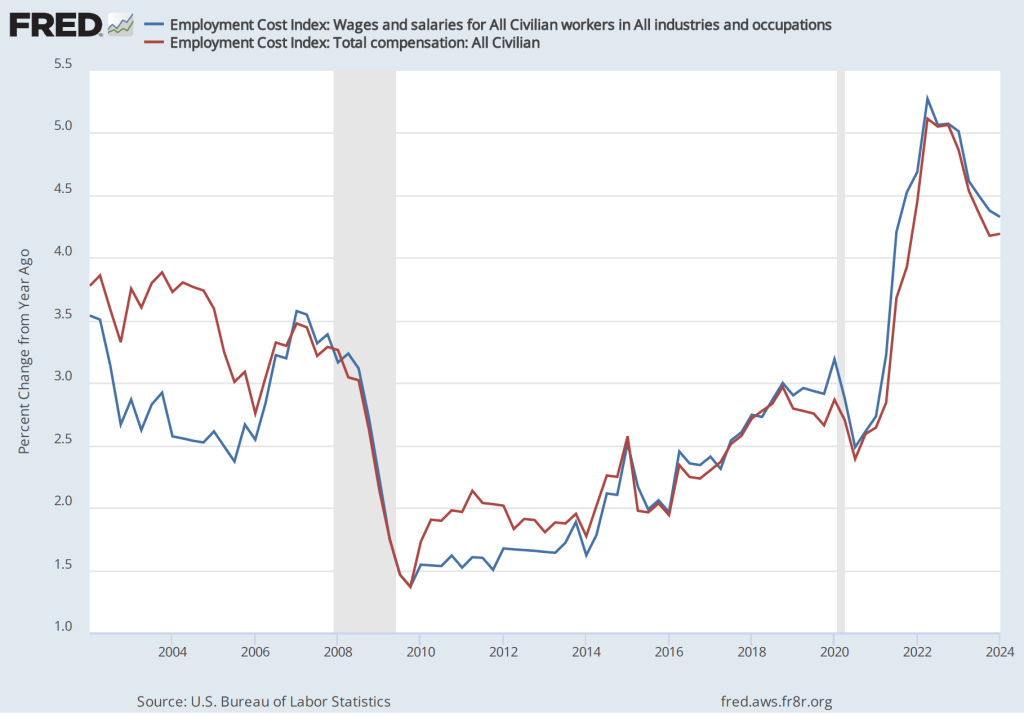

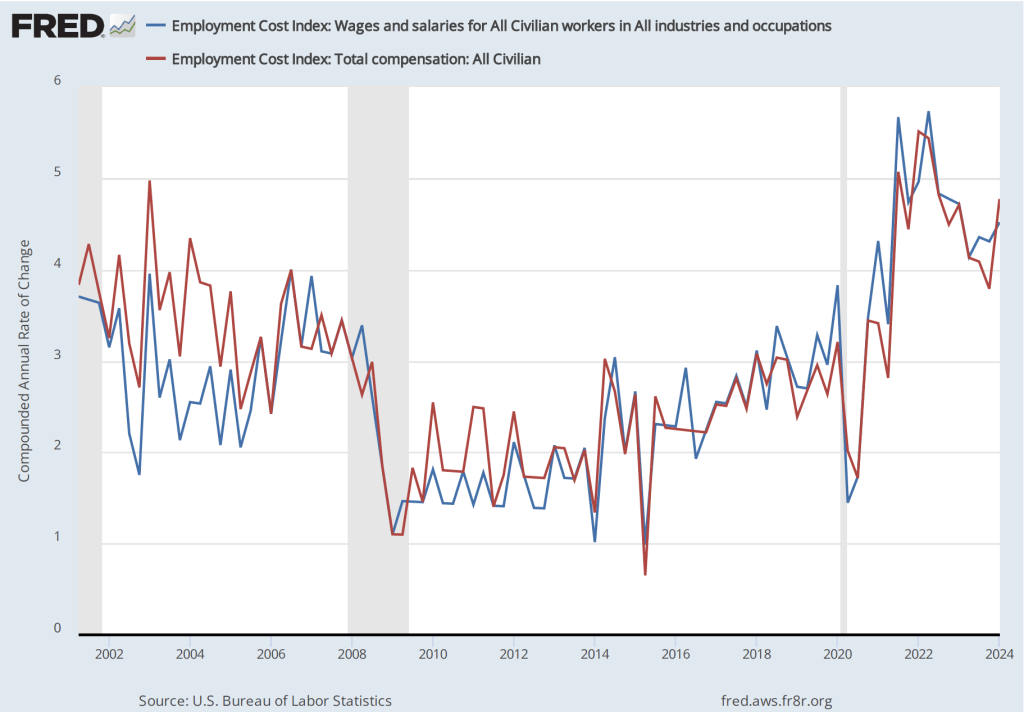

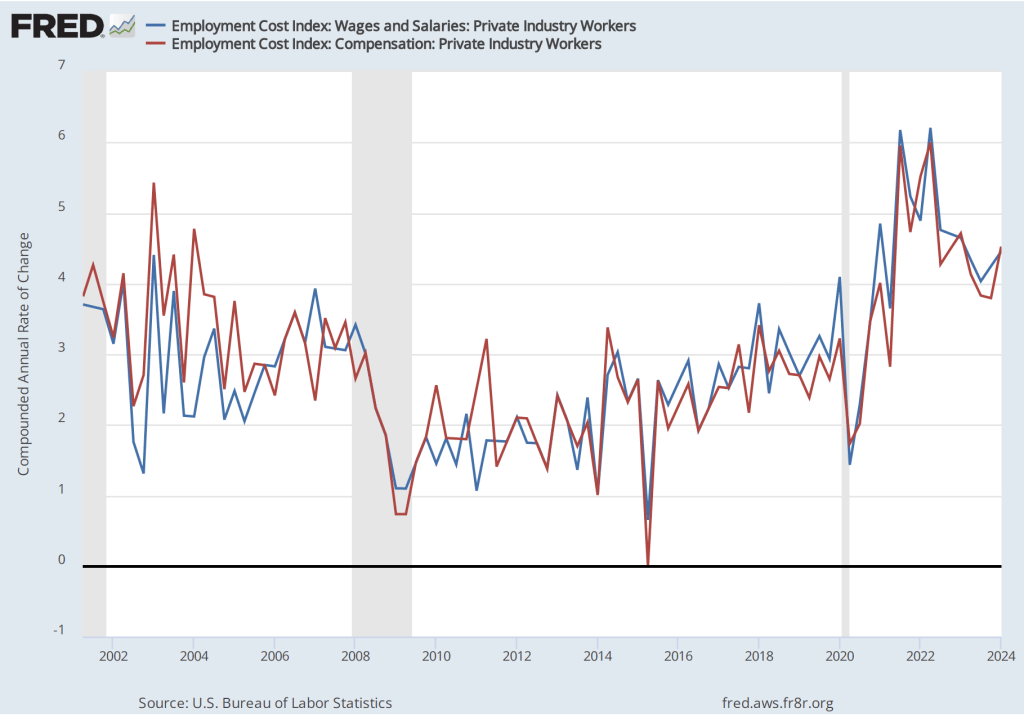

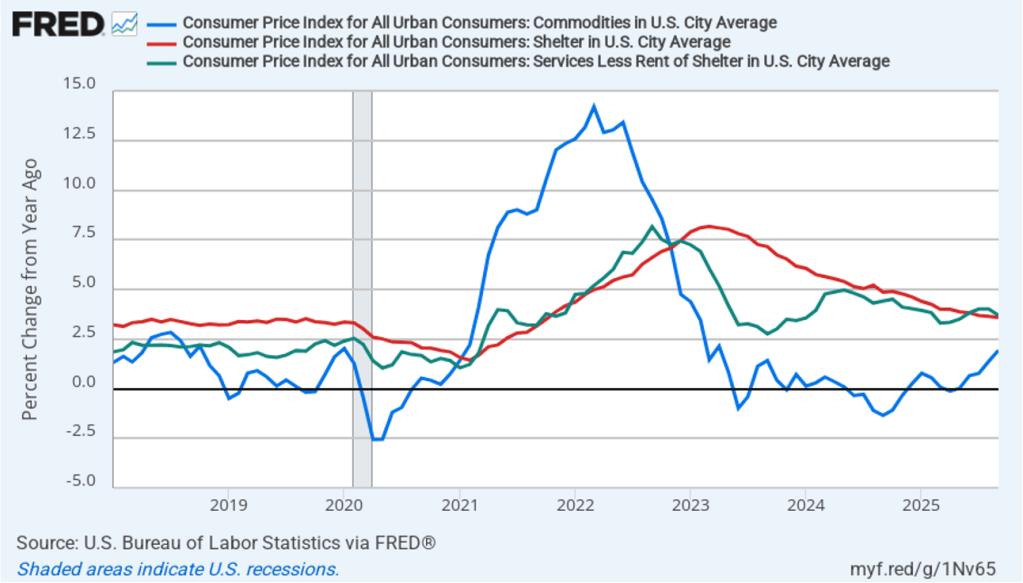

In discussing inflation, Powell highlighted three aspects of the recent CPI report: inflation in goods, inflation in shelter, and inflation in services not including shelter. (The BLS explains is measurement of shelter here.) The following figure shows inflation in each of those categories, measured as the percentage increase from the same month in the previous year. Inflation in goods (the blue line) has been trending up, reflecting the effect of increased tariffs rates. Inlation in shelter (the red line) and in services minus shelter (the green line) have generally been trending downward. Powell noted that the decline in inflation in shelter has been slower than most members of the committee had expected.

Still, Powell argued that with the downward trend in services, once the temporary inflation in goods due to the effects of tariffs had passed through the economy, inflation was likely to be close the Fed’s 2 percent annual target. He thought this was particularly likely to be true because even after today’s cut, the federal funds rate was “restrictive” because it remained above its long-run nominal and real values. A restrictive monetary policy will slow spending and inflation.

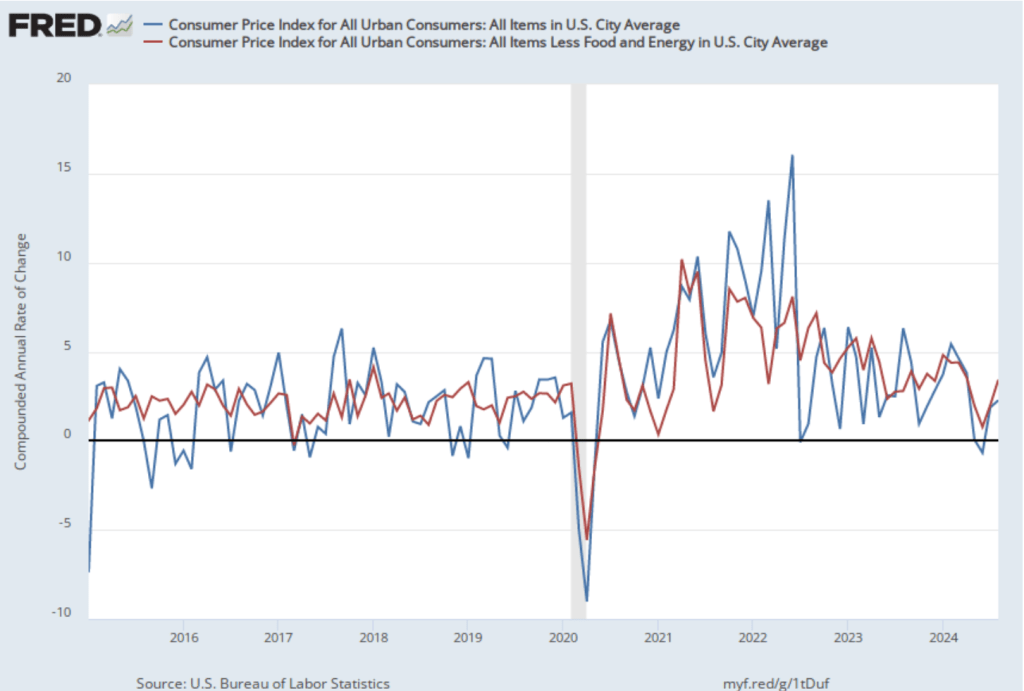

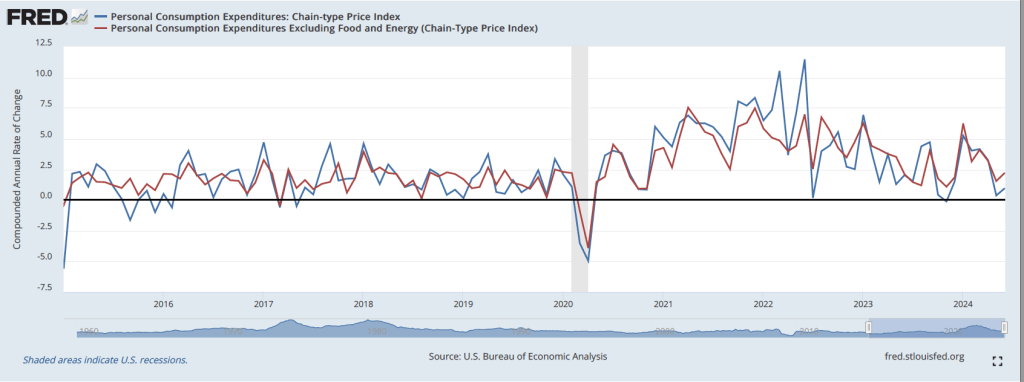

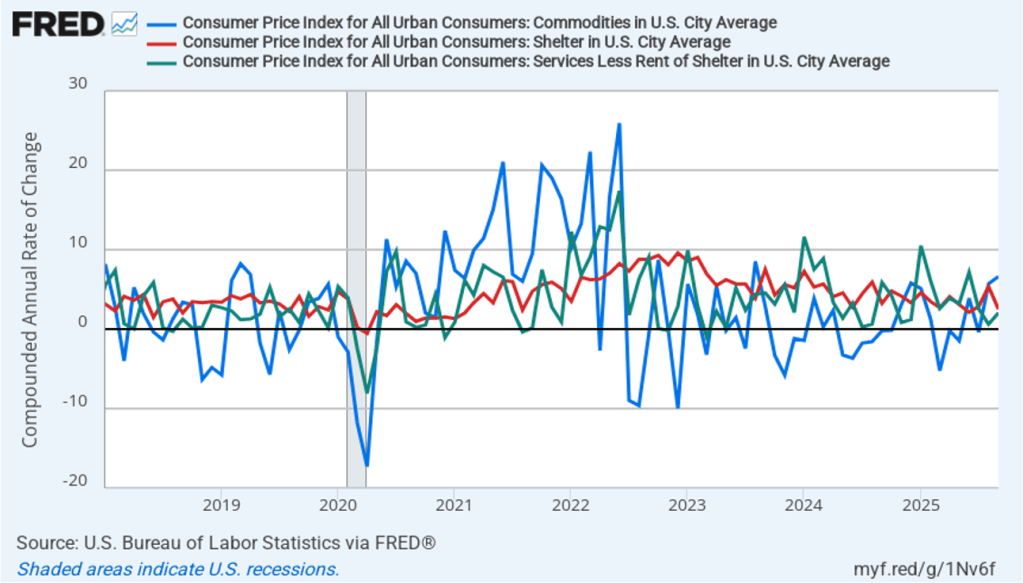

In the following figure, we look at the 1-month inflation rates—that is, the annual inflation rates calculated by compounding the current month’s rates over an entire year—for the same three categories. Calculated as the 1-month inflation rate, goods inflation (the blue line) was running at a very high 6.6 percent in September. inflation in shelter (the red line) had declined to 2.5 per cent in September. Inflation in services minus shelter rose slightly in September to 2.1 percent.

Assuming that the shutdown of the federal government ends within the next few weeks, members of the FOMC will have a great deal of data on inflation, real GDP growth, and employment to consider before their next meeting in December.