Image generated by ChatGPT

On Thursday (December 18) the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released its latest report on the consumer price index (CPI). The federal government shutdown, which lasted from October 1 to November 12, is still affecting the macroeconomic statistics being gathered by the BLS and other agencies. The BLS notes in the report:

“BLS did not collect survey data for October 2025 due to a lapse in appropriations. BLS was unable to retroactively collect these data. For a few indexes, BLS uses nonsurvey data sources instead of survey data to make the index calculations. BLS was able to retroactively acquire most of the nonsurvey data for October. CPI data collection resumed on November 14, 2025.”

The following table from the CPI report gives an indication of how much data that is normally collected wasn’t collected in October or November.

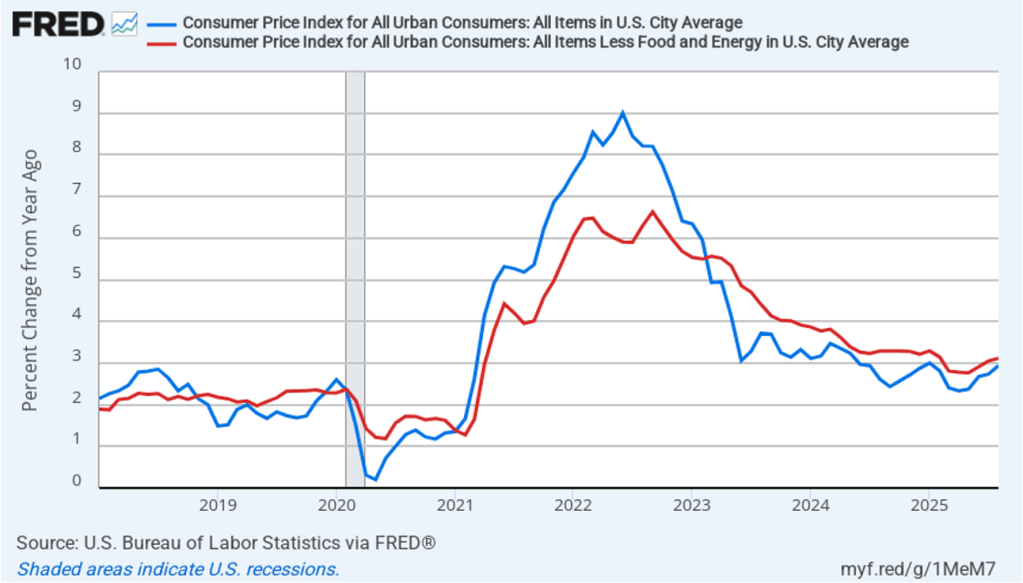

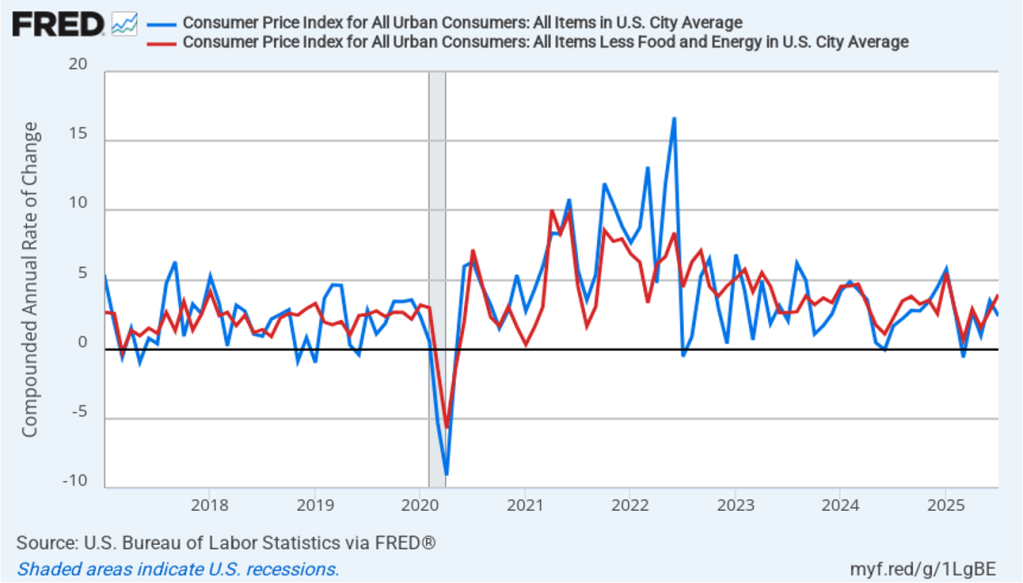

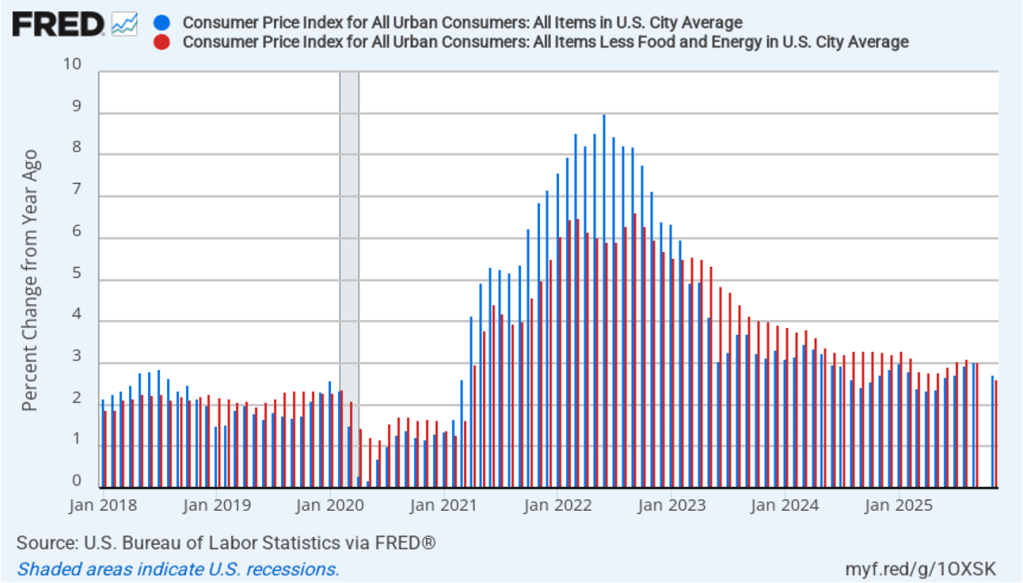

Bearing in mind the missing data, the following figure compares headline CPI inflation (the blue bar) and core CPI inflation (the red bar) as reported in this month’s CPI report.

- The headline inflation rate, which is measured by the percentage change in the CPI from the same month in the previous year, was 2.7 percent in November, down from 3.0 in September.

- The core inflation rate, which excludes the prices of food and energy, was 2.6 percent in November, down from 3.0 percent in September.

Economists who were surveyed by Fact Set had forecast that both headline inflation and core inflation would rise to 3.1 percent in November. Economists surveyed by the Wall Street Journal also forecast that headline inflation would rise to 3.1 percent in November, but forecast that core inflation would rise slightly less to 3.0 percent. It’s unclear whether the economists were aware at the time they were surveyed how much data for October and November would be missing from this month’s report.

Because of how much data that is normally collected was missing from the calculations of November’s inflation rate, the results should be treated with caution. The Wall Street Journal quoted an economist at the investment bank UBS as advising: “I think you largely just put this one to the side. Maybe this report gives a minor downward sign for overall inflation, but the vast, vast majority of this is just noise and should be ignored.”

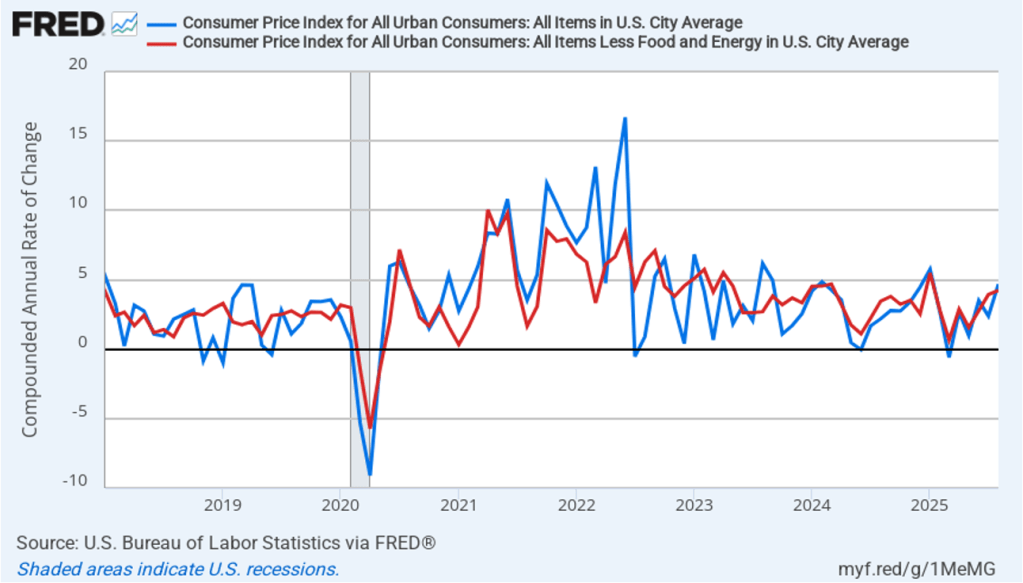

Several economists were concerned about the computation the BLS had to make to deal with the lack of direct data on the price of “shelter.” The price of shelter in the CPI, as explained here, includes both rent paid for an apartment or a house and “owners’ equivalent rent of residences (OER),” which is an estimate of what a house (or apartment) would rent for if the owner were renting it out. OER is included in the CPI to account for the value of the services an owner receives from living in an apartment or house. The following figure shows CPI inflation, measured as the percentage change since the same month in the previous year, leaving out the price of shelter. Measured this way, inflation was 2.6 percent in November, which is slightly lower than the 2.7 percent inflation rate the BLS reported when including all items.

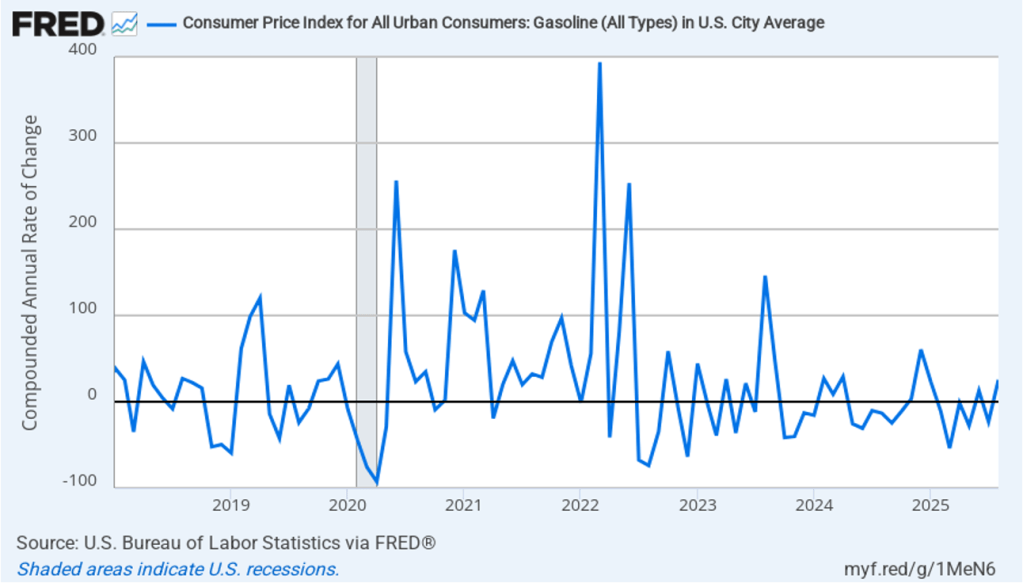

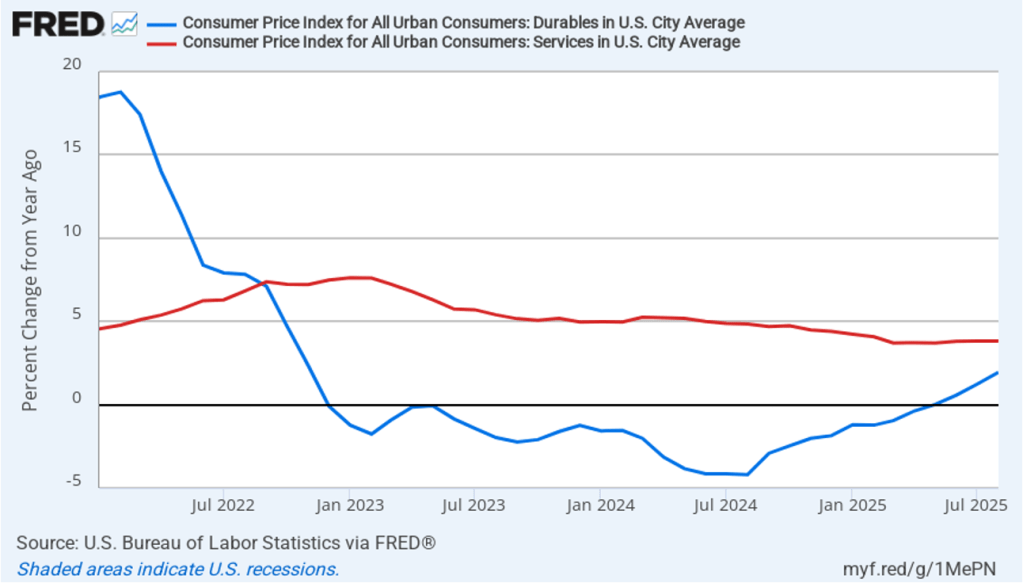

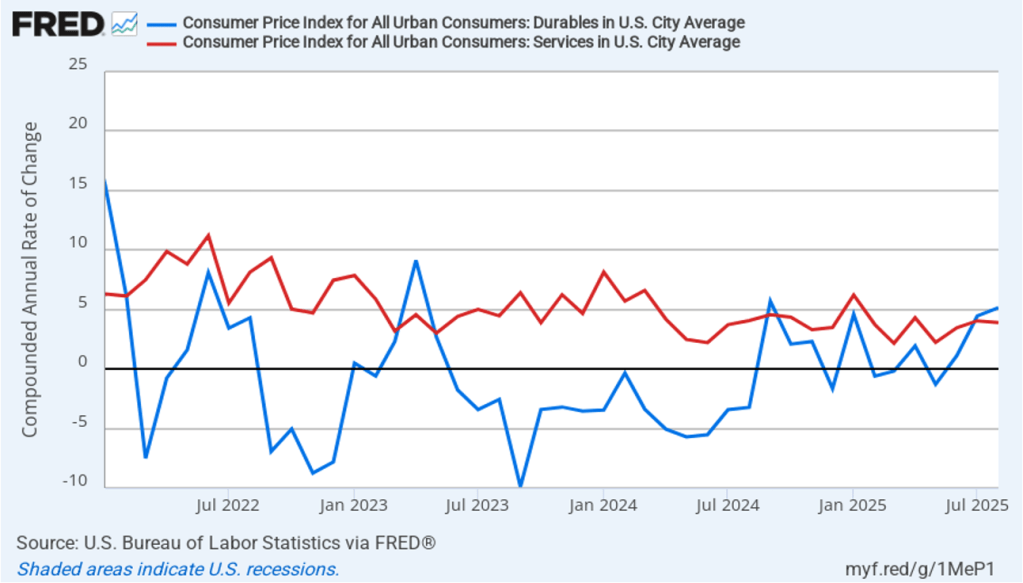

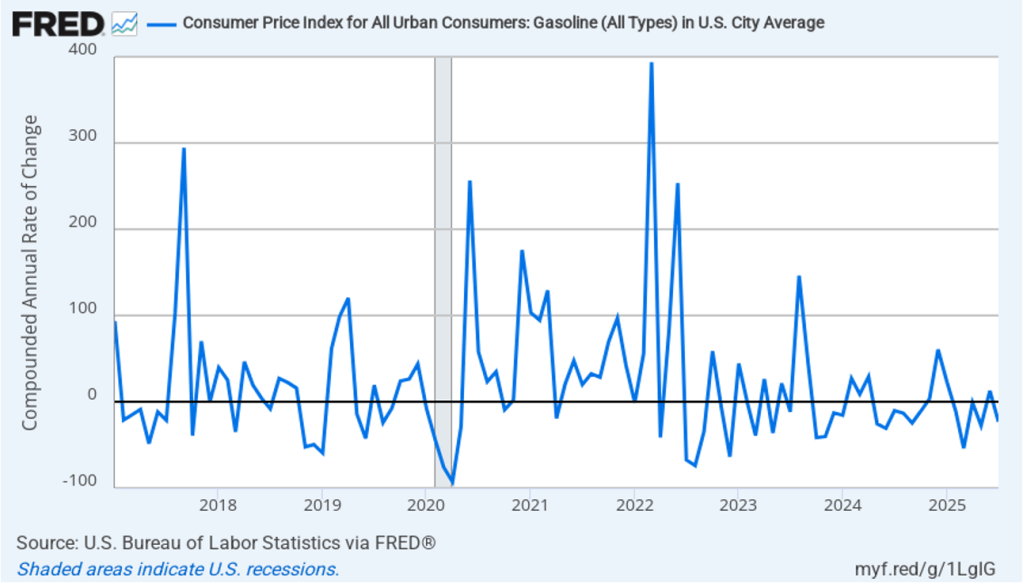

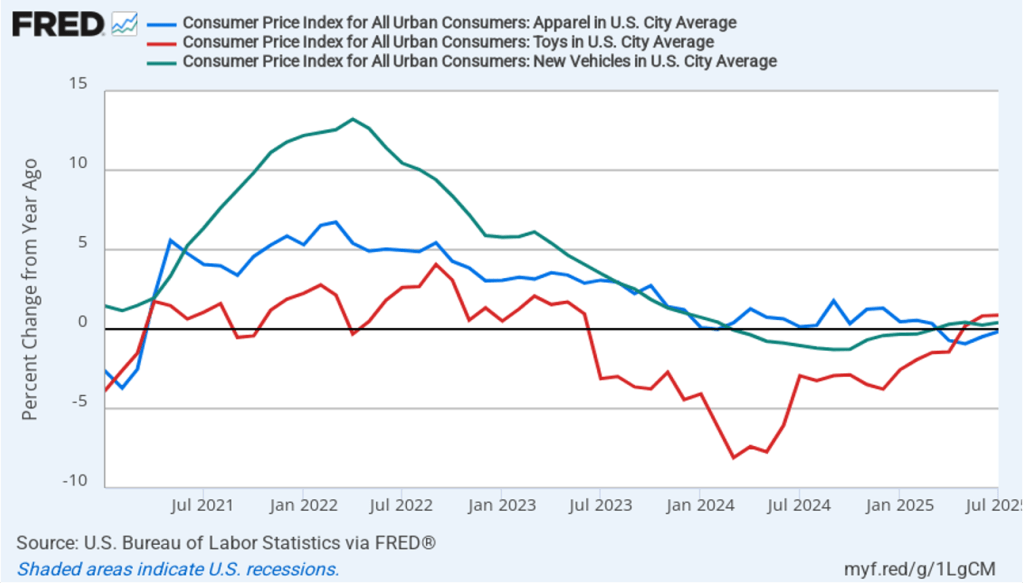

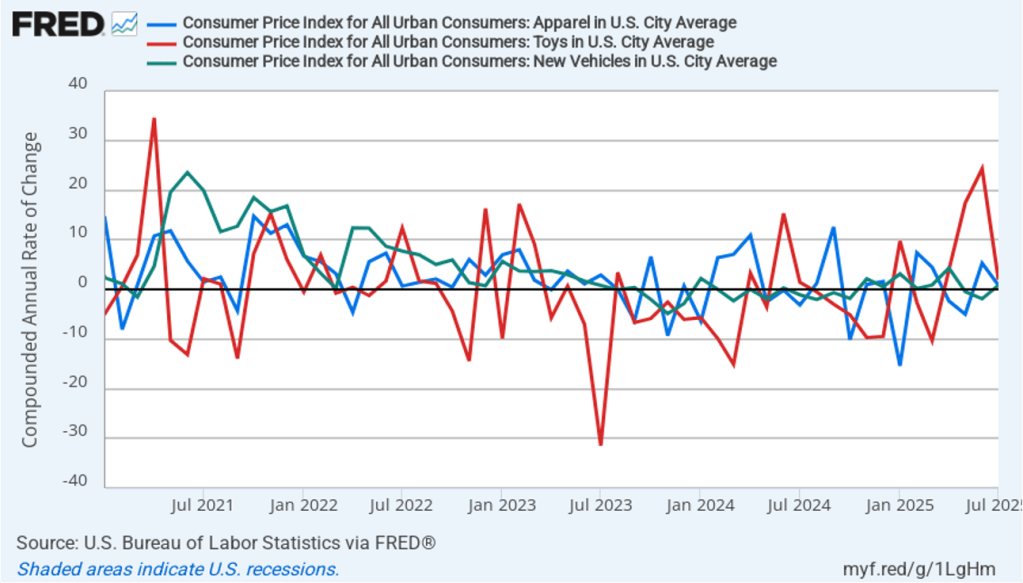

What effect have the tariffs that the Trump administration announced on April 2 had on inflation? (Note that many of the tariff increases announced on April 2 have since been reduced.) The following figure shows 12-month inflation in durable goods—such as furniture, appliances, and cars—which are likely to be affected directly by tariffs, and services, which are less likely to be affected by tariffs. To make recent changes clearer, we look only at the months since January 2022. In November, inflation in durable goods decreased to 1.8 percent from 2.2 percent in September. Inflation in services in November was 3.2 percent, down from 3.6 percent in September. So the upward pressure on goods prices from the tariffs seems to be declining. But, again, missing data makes it’s unclear to what extent November inflation numbers are representative of what’s actually happening currently to prices.

It’s unlikely that this inflation report will have much effect on the views of the members of the Federal Reserve’s policymaking Federal Open Market Committee. In a press conference after the committee’s most recent meeting, Fed Chair Jerome Powell cautioned against drawing firm conclusions from data for October and November:

“I should mention on the data, as long as I’m talking about it, that we’re going to need to be careful in assessing particularly the household survey data. There are very technical reasons about the way data are collected in some of these measures, both in, you know, inflation and in labor—in the labor market so that the data may be distorted. And not just sort of more volatile, but distorted. And that—it’s—and that’s really because data was not collected in October and half of November. So we’re going to get data, but we’re going to have to look at it carefully and with a somewhat skeptical eye by the time of the January meeting ….”