Supports: Macroeconomics Chapter 4, Section 4.3, and Chapter 14, Section 14.3 and Economics, Chapter 4, Section 4.3, and Chapter 24, Section 24.3.

Image created by ChatGPT

Credit cards provide two main services: 1) They are more convenient to use than cash and are more widely accepted than are personal checks, and 2) they are a source of short-term credit. People who pay their balances off at the end of each month get (very short-term) credit for free. People who don’t pay their balances off have to pay interest on the unpaid balance. Credit cards are the leading source of short-term credit to small businesses. We can think of the interest rate on credit card balances as the price of credit card services, although people who pay off their balances each month avoid paying this price. (Note that banks and other credit card issuers also earn fees from merchants who accept credit cards. These processing fees are usually between 1.5 percent and 3.5 percent of the price of the transaction.)

President Trump announced that he intends to cap the interest rate on credit cards at 10 percent. (Imposing such a cap is usually thought to require Congressional approval.) Currently, the average interest rate on credit cards is about 21 percent, although interest rates vary across cards due to differences in the awards the cards give to card holders and the credit history of the card holders.

In this problem, we look at the effect of capping credit card interest rates on the market for credit card services. An interest rate cap is effectively a price ceiling, so we can use the analysis in Chapter 4, Section 4.4, “Government Intervention in the Market: Price Floors and Price Ceilings” to analyze the effect of the interest rate cap on the market for credit card services. We briefly discuss the effects of a cap on credit card interest rates in the Apply the Concept “Help for Young Borrowers: Fintech or Ceilings on Interest Rates?” in Chapter 14, Section 14.3.

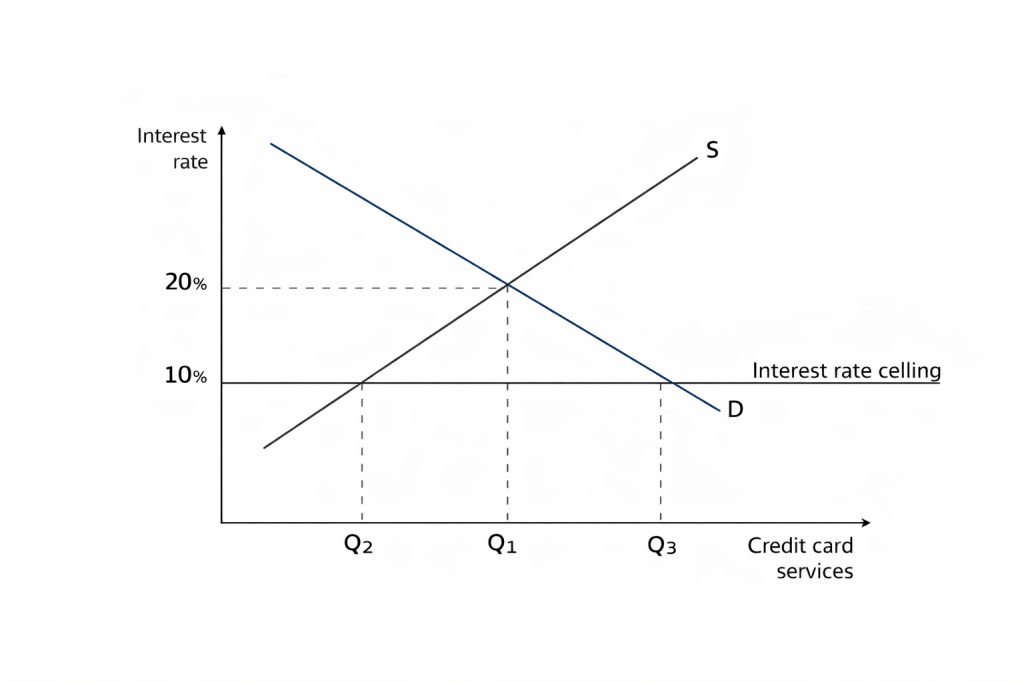

- Use a demand and supply graph to illustrate the effect of a cap on credit card interest rates on the market for credit card services. Be sure that your graph shows the equilibrium price (interest rate) and quantity of credit card services before and after the imposition of the cap. Briefly explain why you would expect the demand curve for credit card services to be downward sloping and the supply curve for credit card services to be upward sloping.

- Which groups would you expect to be most affected and which would you expect to be least affected by the imposition of a cap on credit card interest rates?

Solving the Problem

Step 1: Review the chapter material. This problem is about the effect of an interest rate cap on the market for credit card services, so you may want to review Chapter 4, Section 4.4, “Government Intervention in the Market: Price Floors and Price Ceilings” and the Apply the Concept “Help for Young Borrowers: Fintech or Ceilings on Interest Rates?” in Chapter 14, Section 14.3.

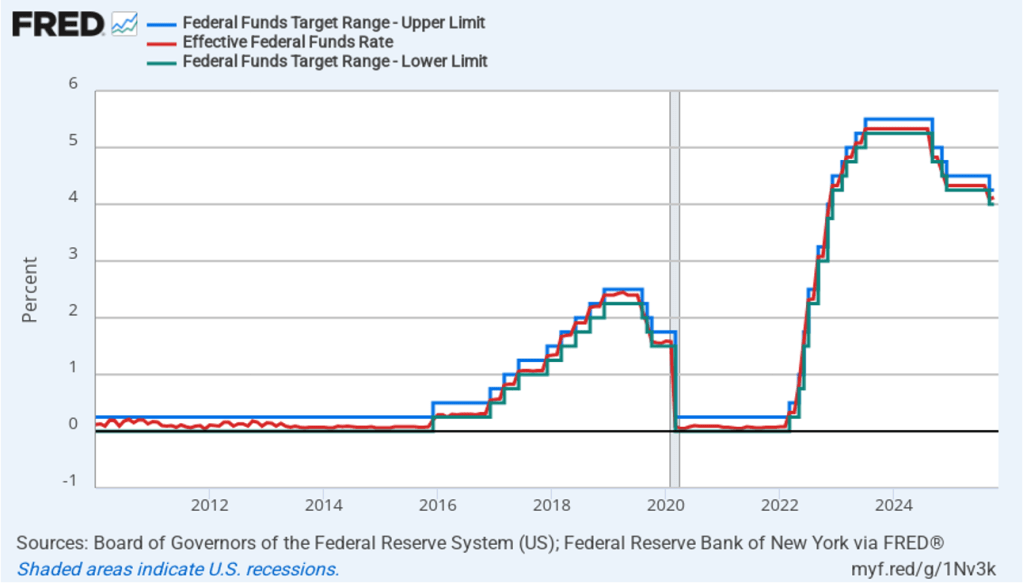

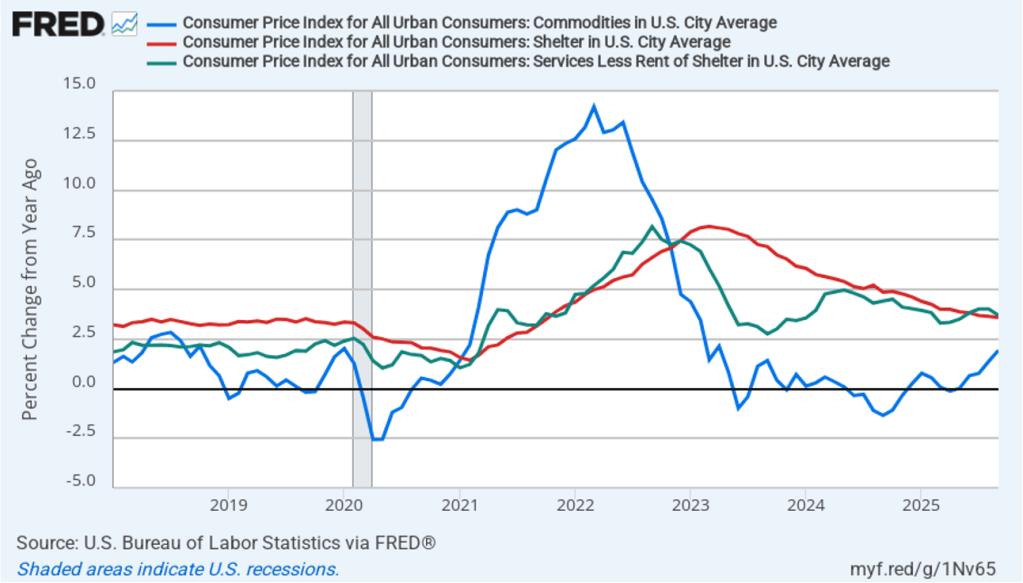

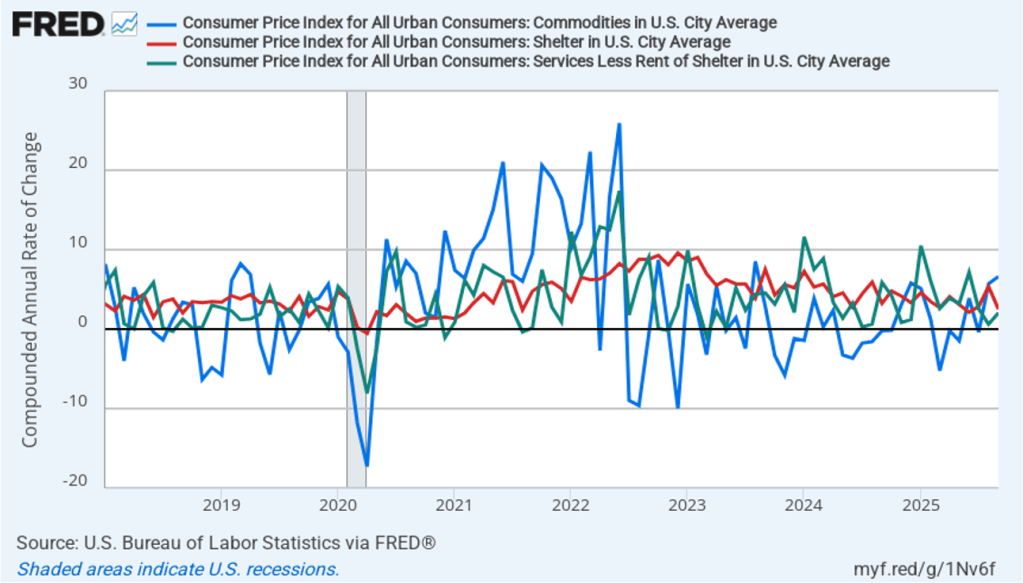

Step 2: Answer part a. by drawing a demand and supply graph of the market for credit card services that illustrates the effect of an interest rate cap. The following figure is simlar to Chapter 4, Figure 4.10, which shows the effect of rent control on the market for rental apartments. We can show the interest rate cap as a horizontal line at an interest rate of 10%. The inital equilibrium, before the imposition of a cap, is at an interest rate of 20 percent and a quantity of credit card services, Q1, where the demand curve for credit card services crosses the supply curve for credit card services. After imposition of the interest rate ceiling, the equilibrium interest falls to 10 percent and the equilibrium quantity of credit card services falls from Q1 to Q2.

We would expect that the higher the interest rate on credit card balances, the fewer the quantity of credit card services consumers will demand. Therefore, the demand curve for credit card services should be downward sloping. We would also expect that the higher the interest rate on credit card balances, the great the quantity of credit card services that banks and other credit card issuers will supply. Therefore, the supply curve for credit card services should be upward sloping.

Step 2: Answer part b. by discussing which groups you would expect to be most affected and which you would expect to be least affected by the imposition of a cap on credit card interest rates. The figure shows that after the imposition of an interest rate ceiling there is a shortage of credit card services equal to the quantity Q3 – Q2. Because Q2 is less than Q1, we know that some people who would have credit cards prior to the imposition of the interest rate ceiling will no longer be able to qualify for them. These people will be affected most by the interest rate cap. We would expect that people who have a higher risk of defaulting on their credit card balances would be most likely to be unable to obtain credit cards following the imposition of the interest rate cap because credit card issuers won’t be able to charge them an interest rate high enough to compensate the issuers for the higher risk of default. In addition, those people who are still able to receive credit cards and who typically don’t pay off their balance each month will benefit from the decline in the interest rate on unpaid balances from 20 percent to 10 percent.

The people who pay off their balances each month will be least affected because they weren’t paying interest. There are some complications, however. Credit card issuers may respond to the interest rate cap by reducing the rewards—such as cash back on their purchases or points toward buying airline tickets or hotel stays—that card holders receive for using their cards. Reducing rewards would affect even those people who pay off their balances each month.

Extra credit: There has been a debate over how many people would be affected by the imposition of a cap on credit card interest rates. For example, Brian Shearer of Vanderbilt University argues that credit card issuers will only modestly reduce the number of people with weak credit histories who they will no longer be willing to issue credit cards to. Paul Calem and Alexander Kim of the Bank Policy Institute, a banking industry trade group, argue that up to two-thirds of people who currently fail to pay off their credit card balances each month are likely to no longer qualify for credit cards or will qualify for credit cards will lower dollar limits following the imposition of a credit card cap.