Photo from cnbc.com

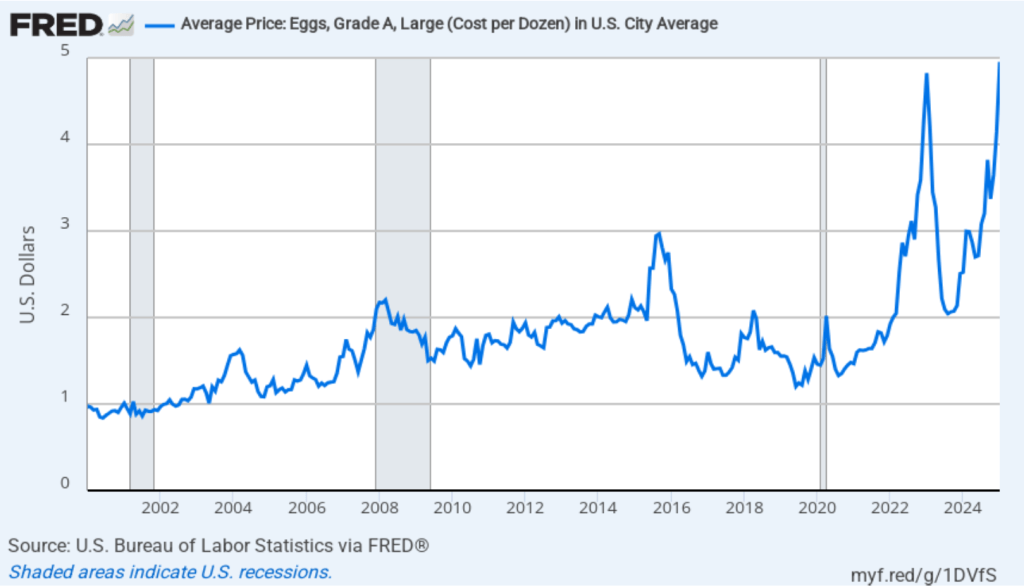

What causes consumer demand for a product to decline? Why does demand for some products suddenly rise? As we discuss in Chapter 3, changes in the relative price of a substitute or a complement cause the demand for a good to shift. For instance, the following figure shows the recent rapid increase in the price of eggs, due in part from the spread of bird flu. We would expect that the increase in the price of eggs will shift to the right the demand curve for egg substitutes, such as the product shown below the figure.

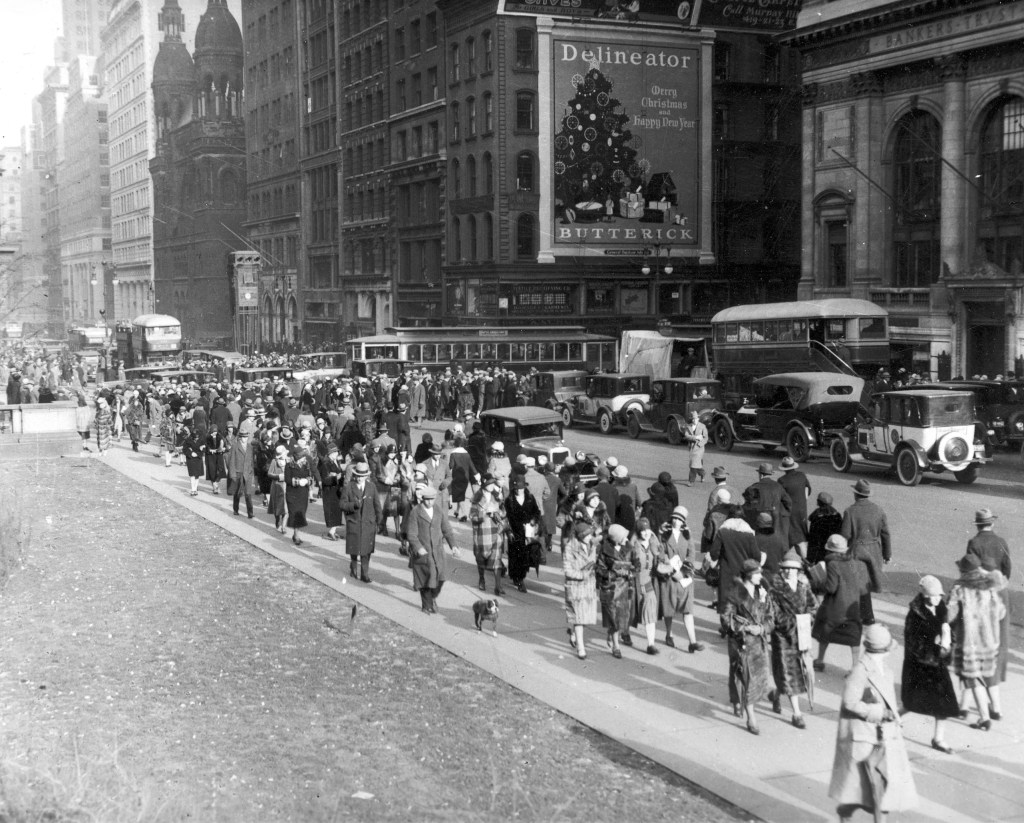

Sometimes a shift in the demand for a product represents a change in consumer tastes. For instance, as we discuss in an Apply the Concept in Chapter 3, for decades most people wore a hat while outdoors. The first photo below shows people walking down a street in New York City in the 1920s. Beginning in the 1960s, hats started to fall out of fashion. As the second photo shows, today few people wear hats—unless they’re walking outside during the winter in the Northeast or the Midwest!

Photo from the New York Daily News

Photo from the New York Times

Technological change can also affect the demand for goods. For example, the development of network television, beginning in the late 1940s, reduced the demand for tickets to movie theaters. Similarly, the development of the internet reduced the demand for physical newspapers.

A recent example of technological change having a substantial effect on a number of consumer goods is the introduction of GLP–1 drugs, beginning in 2005. These drugs, such as Ozempic and Mounjaro, were first developed to treat type 2 diabetes. The drugs were found to significantly reduce appetite in most users, leading to users losing weight. Accordingly, doctors began to prescribe the drugs to treat obesity. By 2025, about half of the users of GLP–1 drugs were doing so to lose weight. A recent article in the Washington Post quoted Jan Hatzius, chief economist at Goldman Sachs, as predicting that by 2028, 60 million people in the United States will be taking a GLP–1 drug.

Many consumers who use these drugs decide to change the mix of foods they eat. Typically, users demand fewer ultra-processed foods, such as chips, cookies, and soft drinks. The percentage of people in the United States who are considered obese—having a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or greater—had been increasing for decades before declining slightly in 2023, the most recent year with available data. It seems likely that the increasing use of GLP–1 drugs helps to explain the decline in obesity.

People taking these drugs have also typically increased the share of foods they eat with higher levels of protein and fiber. These changes in diet are likely to lead to improved health, reducing the demand for some medical services. The number of people experiencing significant weight loss has already begun to reduce demand for extra-large clothing sizes and increase the demand for medium clothing sizes.

How much has the use of Ozempic and similar drugs reduced the demand for snacks? A recent study by Sylvia Hristakeva and Jura Liaukonyt of Cornell University and Leo Feler of Numerator, a market research firm, presents numerical estimates of changes in demand for different foods by users of GLP–1 drugs. The authors assembled a representative sample of 150,000 U.S. households and the households’ grocery purchases from July 2022 through September 2024. They estimate that the share of the U.S. population using a GLP–1 drug increased from 5.5% in October 2023 to 8.8% in July 2024.

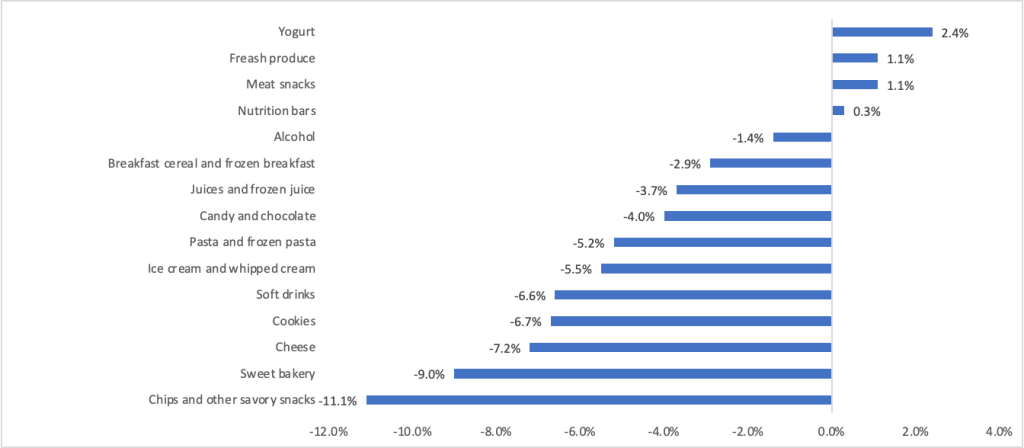

The study finds that households with at least one person using a GLP–1 drug reduced their total grocery shopping by 5.5 percent or $416. The study gathered data on changes in the categories of food that households were buying six months after at least one person in the household began using one of these drugs. The figure below is compiled from data in the study.

As expected, purchases of snacks declined. The category of “chips and other savor snacks” (bottom row in the figure) declined by more than 11 percent. Purchases of sweet bakery products, cheese, cookies, soft drinks, ice cream, and pasta all declined by more than 5 percent. Purchases of yogurt, fresh produce, meat snacks, and nutrition bars, all increased. An article in the Wall Street Journal noted that “food makers are starting to understand better and cater to, in some cases with products specifically designed for” users of this drug. The image below shows some of the new products that Nestle—a major candy producer—has introduced to appeal to users of GLP–1 drugs. Nestle’s Vital Pursuit line of frozen packaged foods contain high levels of protein and fiber.

It’s too early to gauge the full effects of GLP–1 drugs on consumer demand. But it’s already clear that GLP–1 drugs are a striking example of technological change affecting demand in a major industry