Supports: Macroeconomics, Chapter 13, Section 13.3; Economics, Chapter 23, Section 23.3; and Essentials of Economics, Chapter 15, Section 15.3

Image generated by ChatGPT

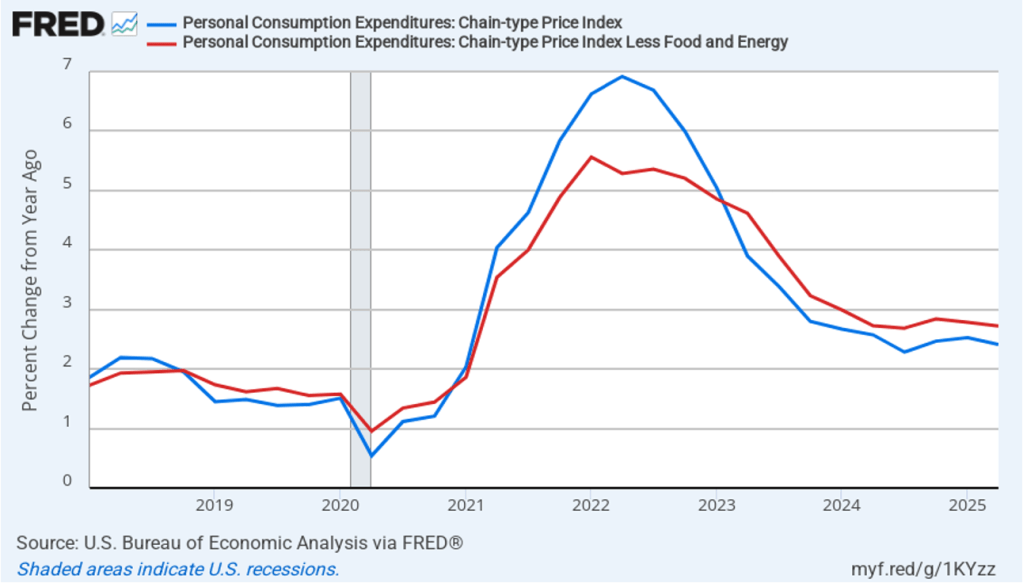

A recent article on axios.com made the following observation: “The mainstream view on the Federal Open Market Committee is based on risk management—that the possibility of a further downshift in the job market appears to be the more pressing concern than the chance that inflation will spiral higher.” The article also notes that: “Tariffs’ effects on inflation are probably a one-time bump.”

a. What is the dual mandate that Congress has given the Federal Reserve?

b. In what circumstances might the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) be faced with a conflict between the goals in the dual mandate?

c. What does the author mean by tariffs’ effects on inflation being a “one-time bump”?

d. What does the author mean by the FOMC engaging in “risk management”? What is a “downshift” in the labor market? If the FOMC is more concerned about a downshift in the labor market than about inflation, will the committee raise or lower its target for the federal funds rate? Briefly explain.

Solving the Problem

Step 1: Review the chapter material. This problem is about the policy dilemma the Fed can face when the unemployment rate and the inflation rate are both rising, so you may want to review Macroeconomics, Chapter 13, Section 13.3, “Macroeconomic Equilibrium in the Long Run and the Short Run.”

Step 2: Answer part a. by explaining what the Fed’s dual mandate is. Congress has given the Fed a dual mandate of achieving price stability and maximum employment.

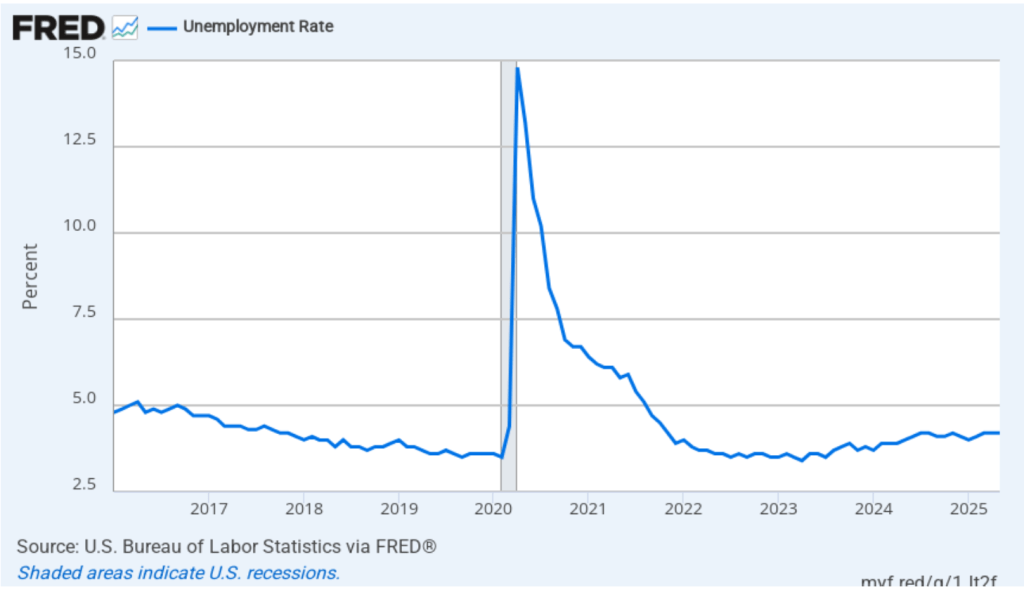

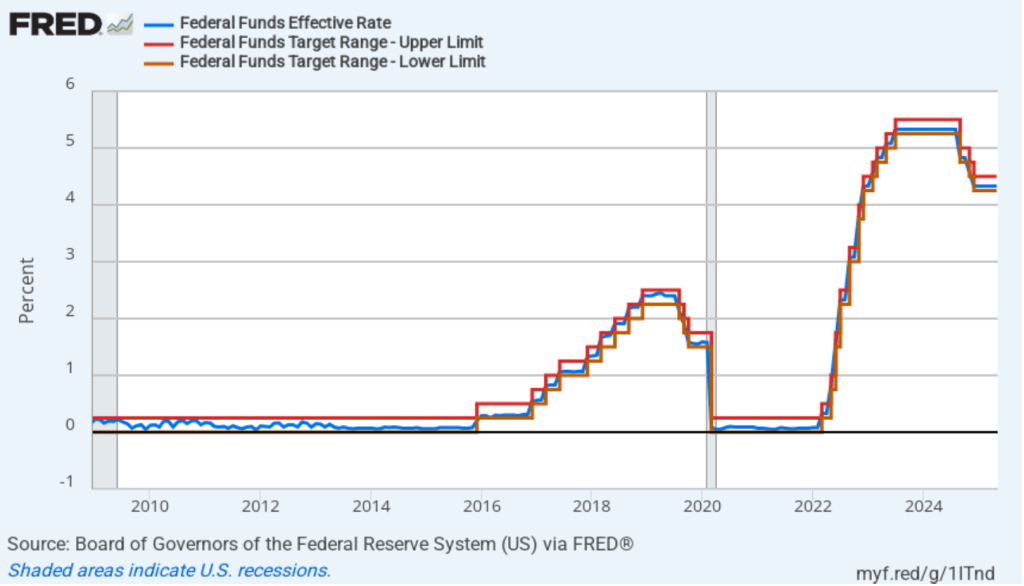

Step 3: Answer part b. by explaining when the FOMC may face a conflict with respect to its dual mandate. When the FOMC is faced with rising unemployment and falling inflation, its preferred policy response is clear: The committee will lower its target for the federal funds rate in order to increase the growth of aggregate demand, which will increase real GDP and reduce unemployment. When the FOMC is faced with falling unemployment and rising inflation, its preferred policy response is also clear: The committee will raise its target for the federal funds rate in order to slow the growth of aggregate demand, which will reduce the inflation rate.

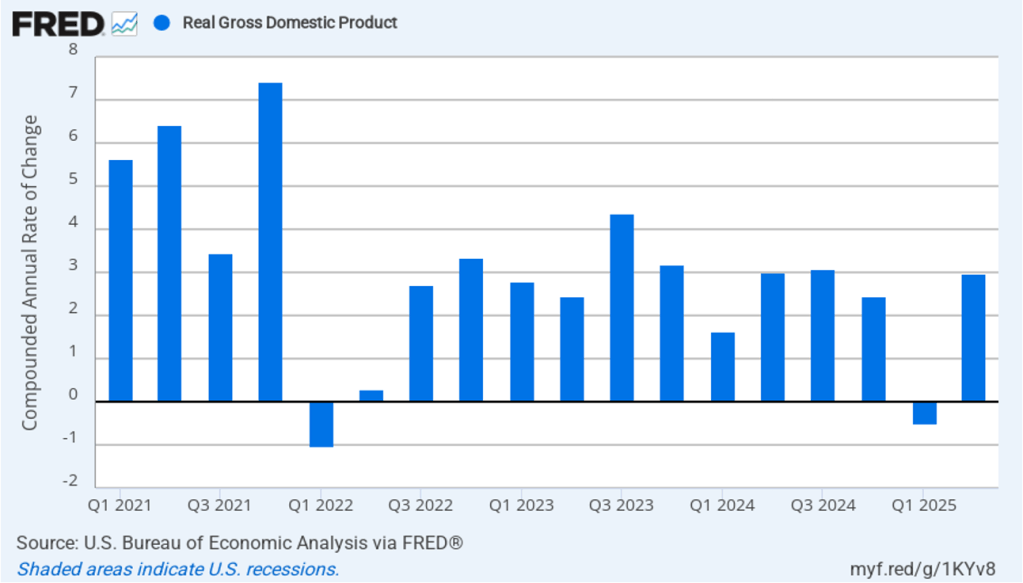

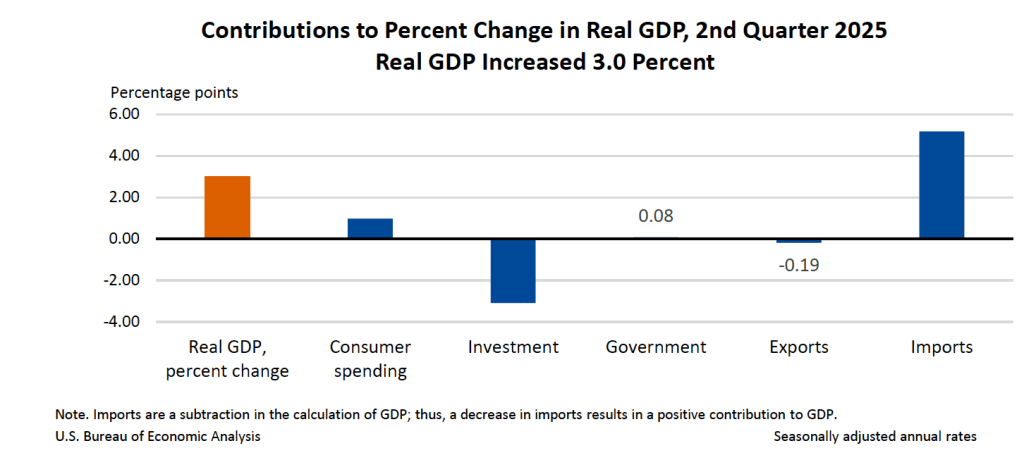

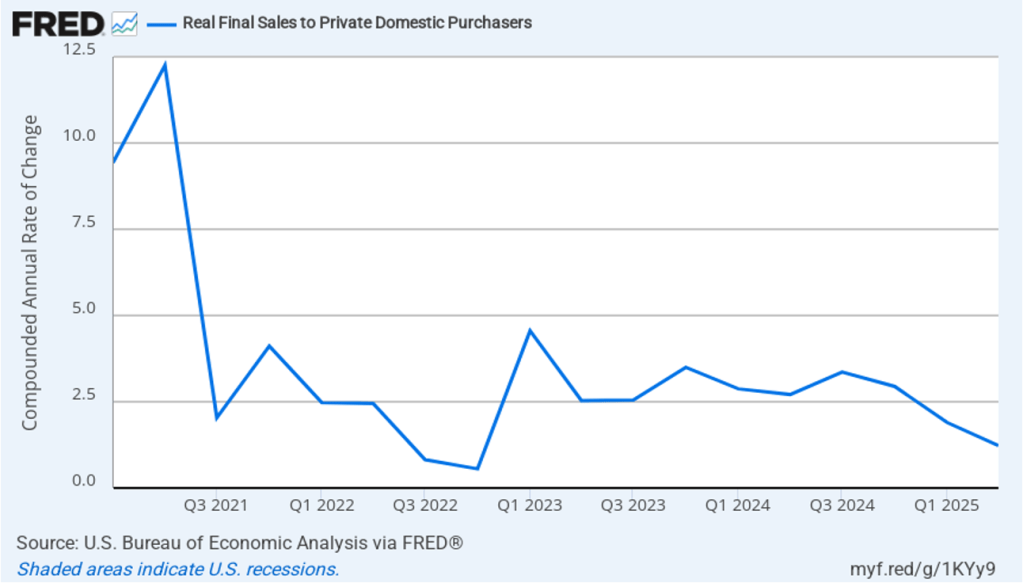

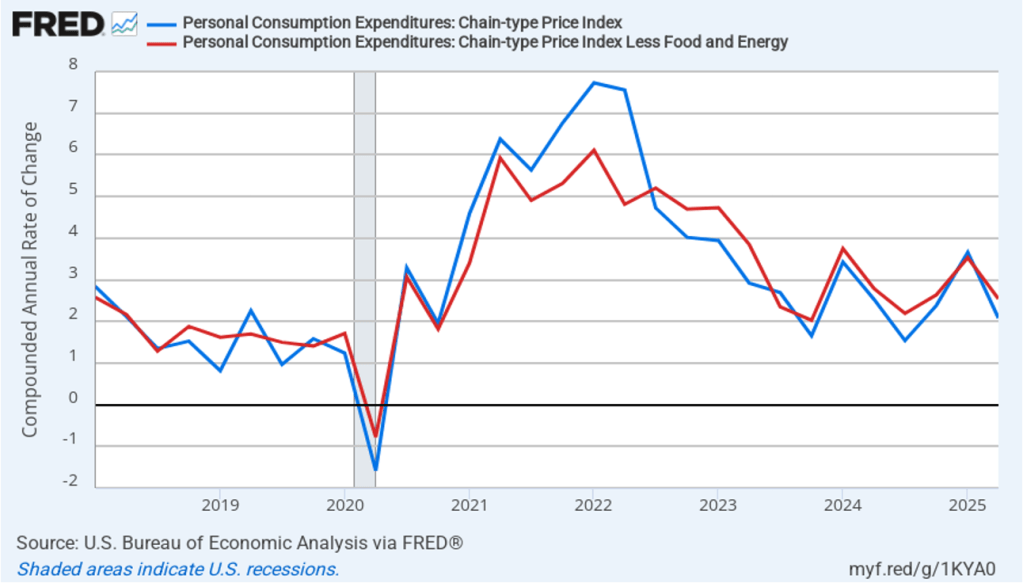

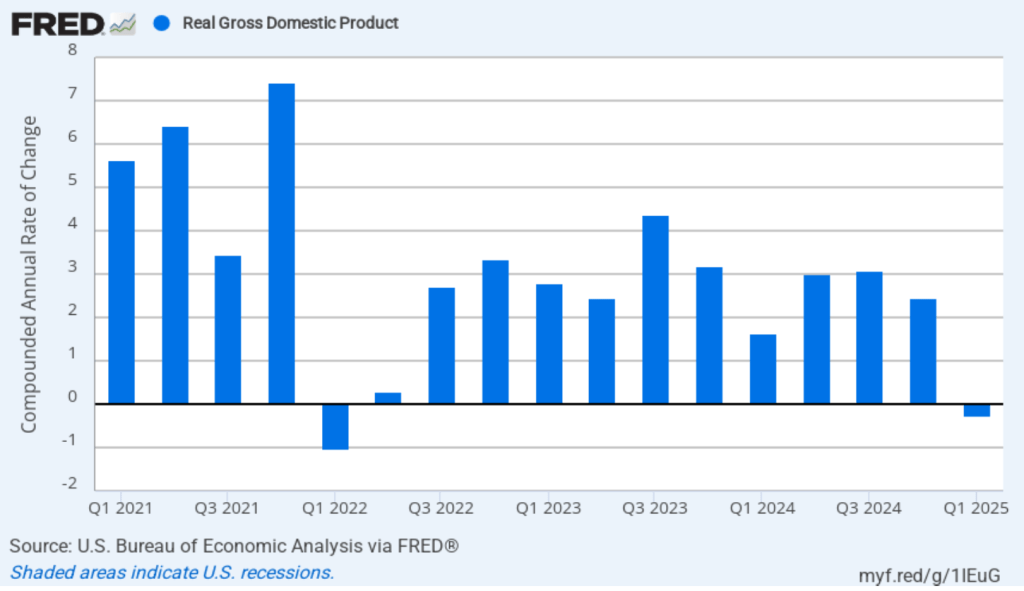

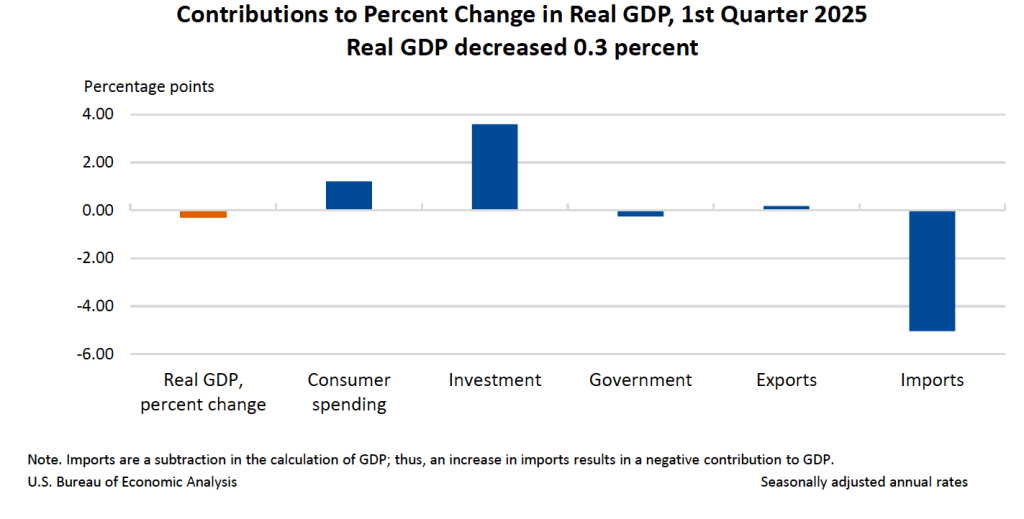

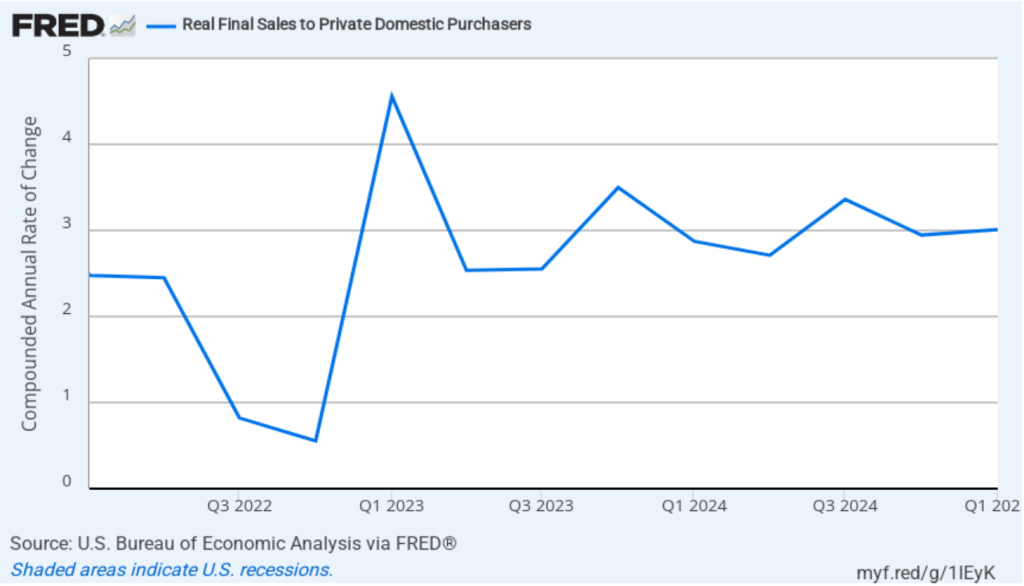

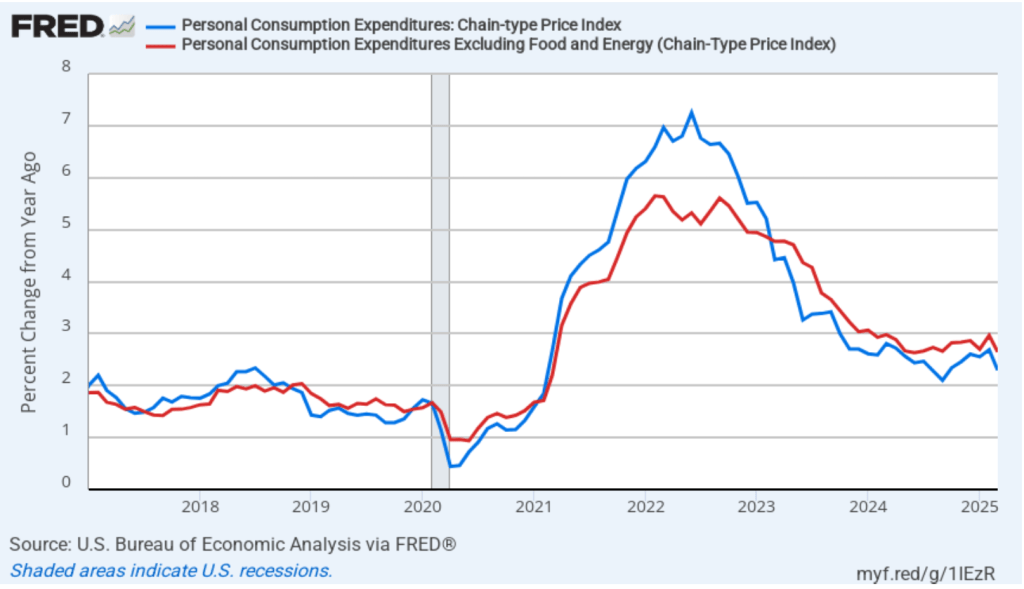

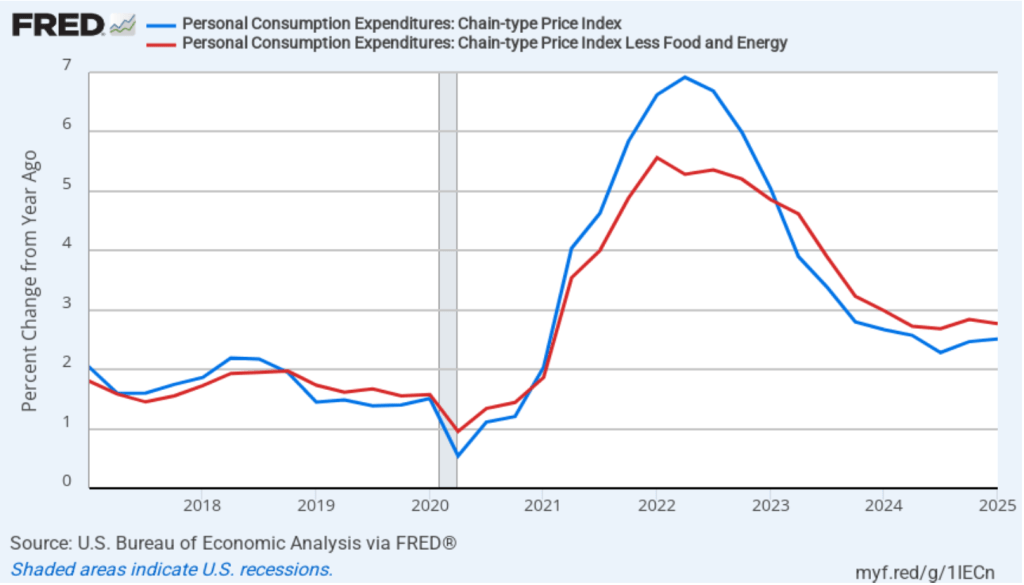

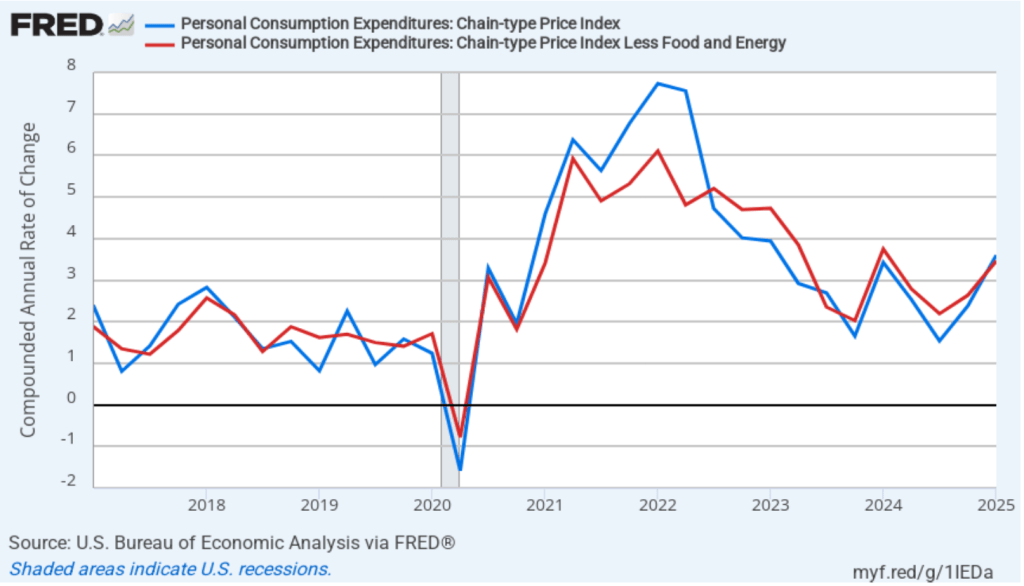

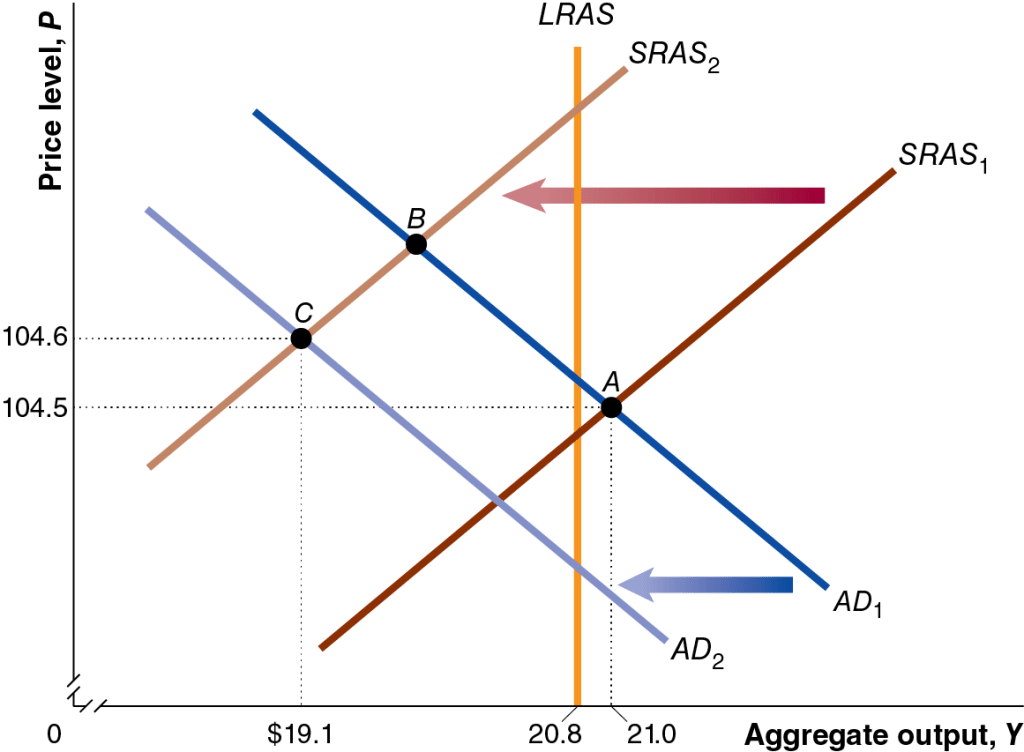

But when the Fed faces an aggregate supply shock, its preferred policy response is unclear. An aggregate supply shock, such as the U.S. economy experienced during the Covid pandemic and again with the tariff increases that the Trump administration began implementing in April, will shift the short-run aggregate supply curve (SRAS) will shift to the left, causing an increase in the price level, along with a decline in real GDP and employment. This combination of rising unemployment and inflation is called stagflation. In this situation, the FOMC faces a policy dilemma: Raising the target for the federal funds rate will help reduce inflation, but will likely increase unemployment, while lowering the target for the federal funds rate will lead to lower unemployment, but will likely increase inflation. The following figure shows the situation during the Covid pandemic when the economy experienced both an aggregate demand and aggregate supply shock. The aggregate demand curve and the aggregate supply curve both shifted to the left, resulting in falling real GDP (and employment) and a rising price level.

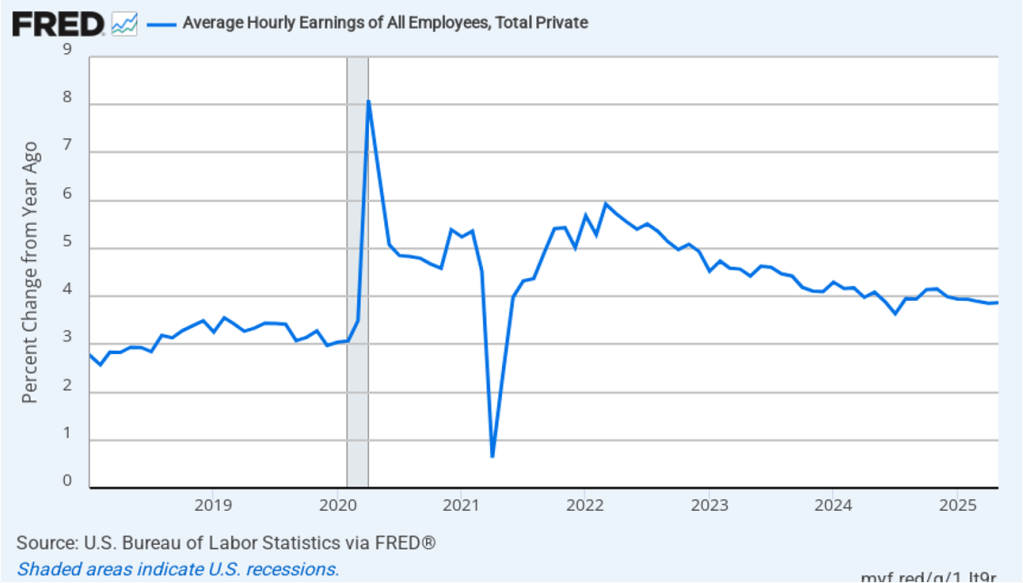

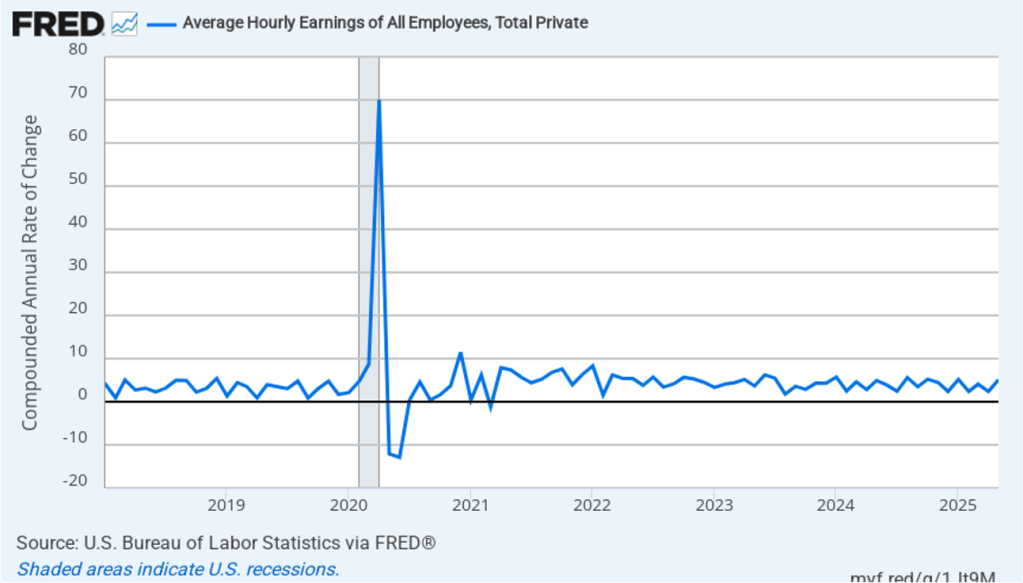

Step 4: Answer part c. by explaining what it means to refer to the effect of tariffs on inflation being a “one-time bump.” Tariffs cause the aggregate supply curve to shift to the left because by increasing the prices of raw materials and other inputs, they increase the production costs of some businesses. Assuming that tariffs are not continually increasing, their effect on the price level will end once the production costs of firms stop rising.

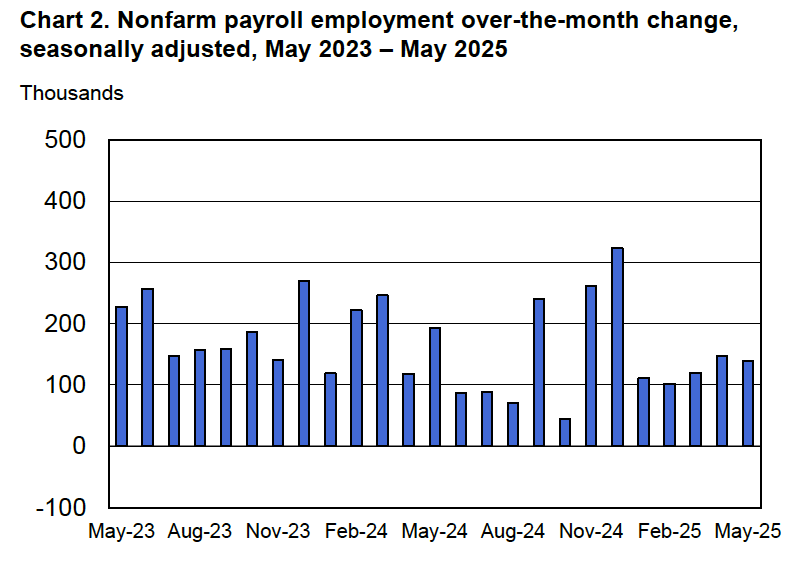

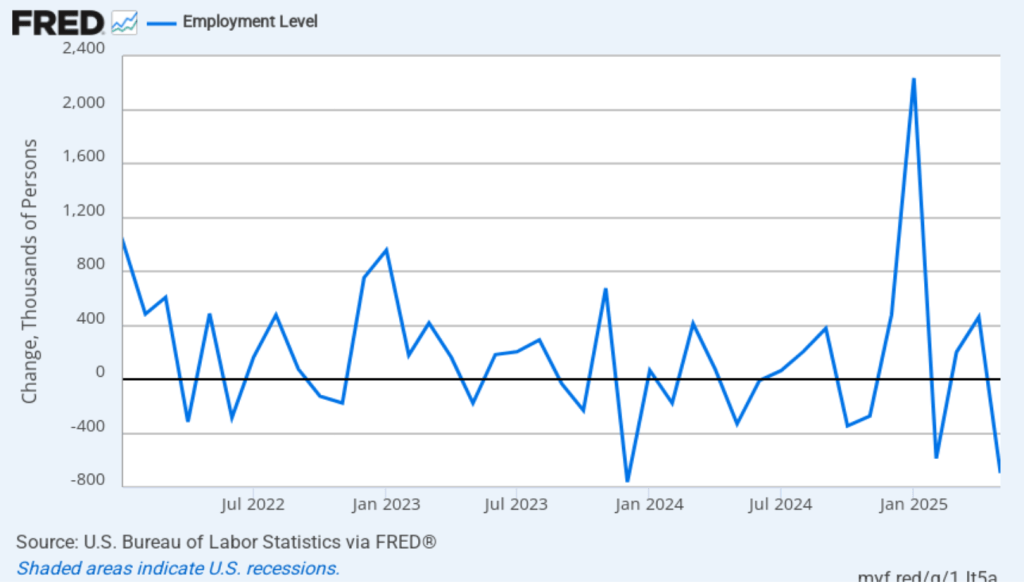

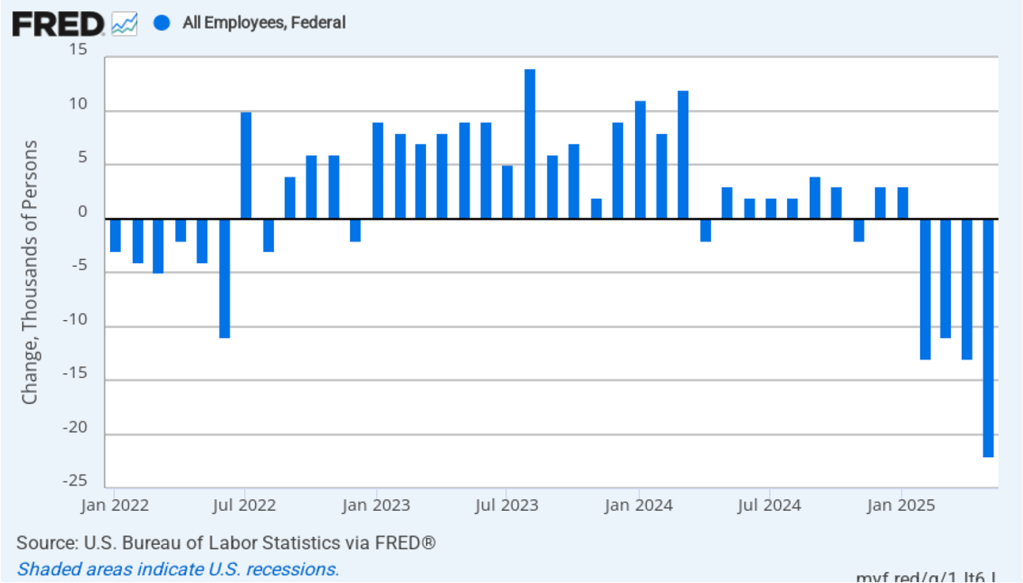

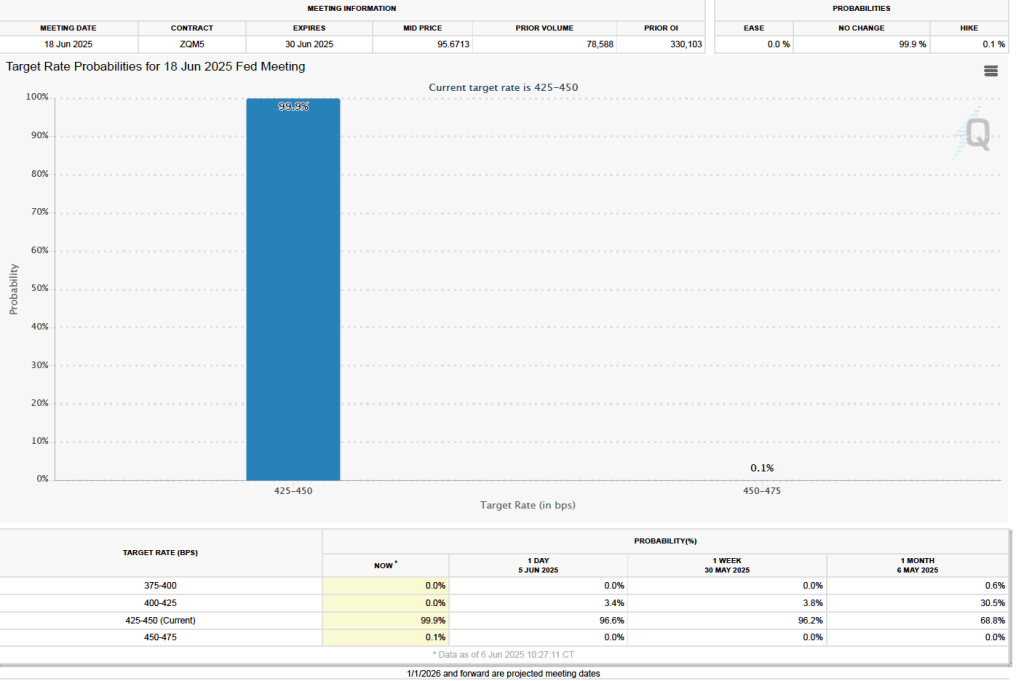

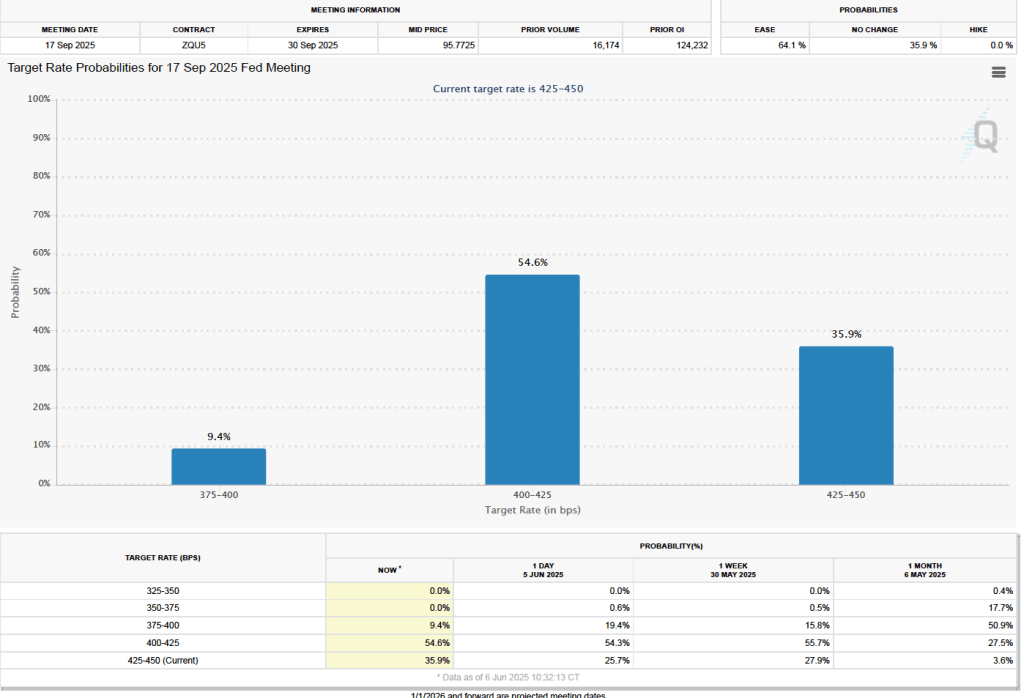

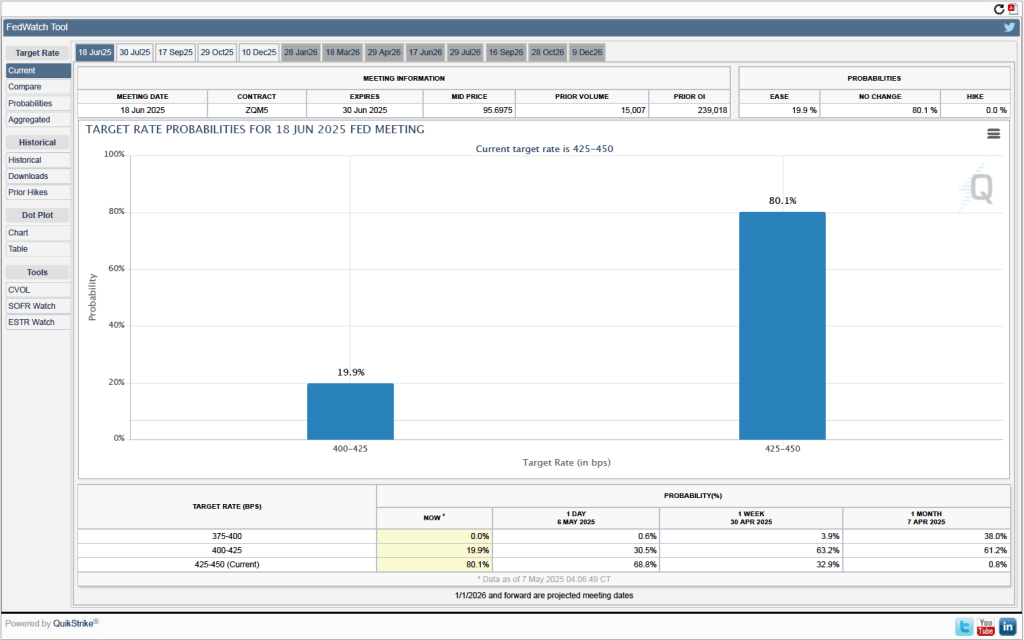

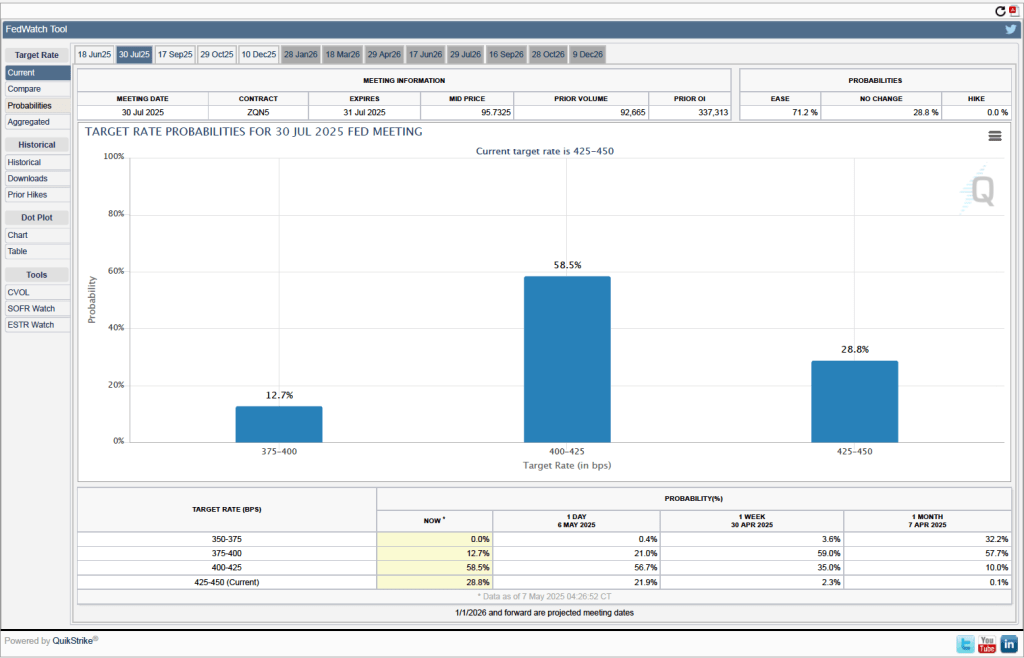

Step 5: Answer part d. by explaining what the author means by the FOMC engaing in “risk management,” explaining what a “downshift” in the labor is, and whether if the FOMC is more concerned about a downshift in the labor market than in inflation, it will raise or lower its target for the federal funds rate. The article refers to the “possibility” of a further downshift in the labor market. A downshift in the labor market means that the demand for labor may decline, raising the unemployment rate. Managing the risk of this possibility would involve concentrating on the maximum employment part of the Fed’s dual mandate by lowering its target for the federal funds rate. Note that the expectation that the effect of tariffs on the price level is a one-time bump makes it easier for the committee to focus on the maximum employment part of its mandate because the increase in inflation due to the tariff increases won’t persist.