The unusual structure of the Federal Reserve System reflects the political situation at the time that Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act in 1913. As we discuss in Money, Banking, and the Financial System, Chapter 13, at that time, many members of Congress believed that a unified central bank based in Washington, DC would concentrate too much economic power in the hands of the officials running the bank. So, the act divided economic power within the Federal Reserve System in three ways: among bankers and business interests, among states and regions, and between the federal government and the private sector.

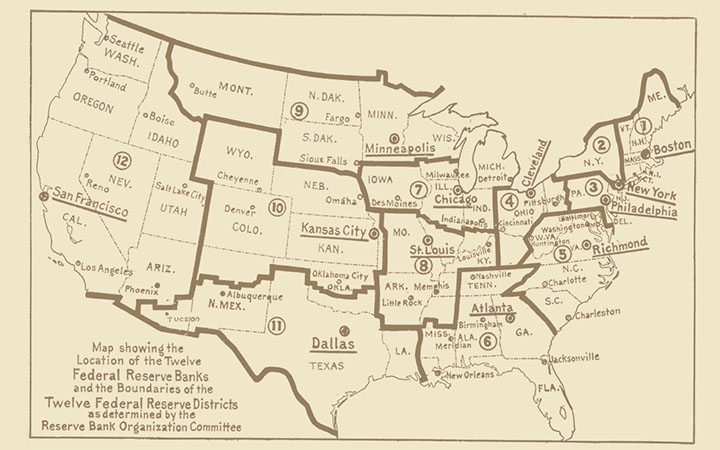

As part of its plan to divide authority within the Federal Reserve System, Congress decided not to establish a single central bank with branches, which had been the structure of both the First and Second Banks of the United States—which were the two attempts by Congress during the period from 1791 to 1836 to establish a central bank. Instead, the Federal Reserve Act divided the United States into 12 Federal Reserve districts, each of which has a Federal Reserve Bank in one city (and, in most cases, additional branches in other cities in the district). The following figure is the original map drawn by the Federal Reserve Organizing Committee in 1913 showing the 12 Federal Reserve Districts. Congress adopted the map with a few changes, following which the areas of the 12 districts have remained largely unchanged down to the present.

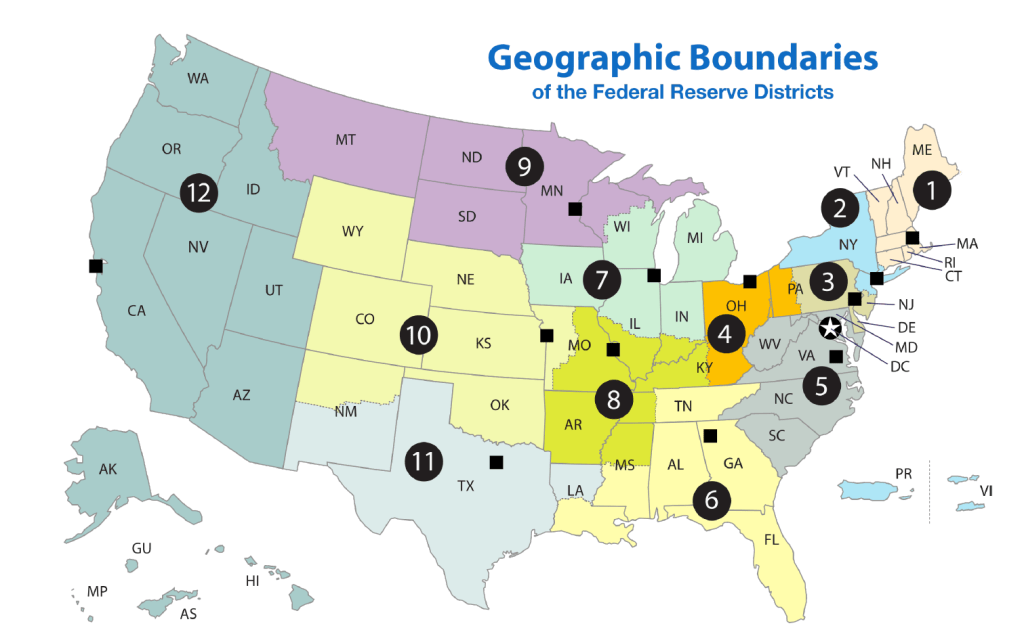

The following map shows the current boundaries of the Federal Reserve Districts.

The map is reproduced from the working paper discussed below.

All national banks—commercial banks with charters from the federal government—were required to join the Federal Reserve System. State banks—commercial banks with charters from state governments—were given the option to join. Congress intended that the primary function of each of the Federal Reserve Banks would be to make discount loans to member banks in its region. These loans were to provide liquidity to banks, thereby fulfilling in a decentralized way the system’s role as a lender of last resort.

When banks join the Federal Reserve System, they are required to buy stock in their Federal Reserve Bank, which pays member banks a dividend on this stock. So, in principle, the private commercial banks in each district that are members of the Federal Reserve System own the District Bank. In fact, each Federal Reserve Bank is a private–government joint venture because the member banks enjoy few of the rights and privileges that shareholders ordinarily exercise. For example, member banks do not have a legal claim on the profits of the District Banks, as shareholders of private corporations do.

On paper, the Federal Reserve System is a decentralized organization with a public-private structure. In practice, power within the system is concentrated in the seven member Board of Governors in Washington, DC. Control over the most important aspect of monetary policy—setting the target for the federal funds rate—is vested in the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). The voting membership of the FOMC consists of the seven member of the Board of Governors, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and four other district bank presidents on a rotating basis (although all 12 district presidents participate in committee discussions). The district bank presidents are elected by the boards of directors of the district banks, but the Board of Governors has final say on who is chosen as a district bank president.

Given these considerations, does the structure of the Fed matter or is it an unimportant historical curiosity? There are reasons to think the Fed’s structure does still matter. First, as we discuss in this blog post, in a recent decision, the U.S. Supreme Court implied—but didn’t state explicitly—that, because of the Fed’s structure, U.S. presidents will likely not be allowed to remove Fed chairs except for cause. That is, if presidents disagree with monetary policy actions, they will not be able to remove Fed chairs on that basis.

Second, as Michael Bordo of Rutgers University and the late Nobel Laureate Edward Prescott argue, the decentralized structure of the Fed has helped increase the variety of policy views that are discussed within the system:

“What is unique about the Federal Reserve, at least compared with other

entities created by the federal government, is that the Reserve Banks’

semi-independent corporate structure allows for ideas to be communicated to

the System . . . . Moreover, it also allows for new and sometimes dissenting views to develop and gestate within the System without being viewed as an expression of disloyalty that undermines the organization as a whole, as would be more likely within a government bureau.”

Finally, recent research by Anton Bobrov of the University of Michigan, Rupal Kamdar of Indiana University, and Mauricio Ulate of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco indicates that the FOMC votes of the district bank presidents reflect economic conditions in those districts. This result indicates that the district bank presidents arrive at independent judgements about monetary policy rather than just reflecting the views of the Board of Governors, which has to approve the appointment of the presidents. The authors analyze the 896 dissenting votes district bank presidents (other than the president of the NY Fed) cast during the period from 1990 to 2017. A dissenting vote is one in which the district bank president voted to either increase or decrease the target for the federal funds relative to the target the majority of the committee favored.

The authors’ key finding is that the FOMC votes of district bank presidents are influenced by the level of unemployment in the district: “a 1 percentage point higher District unemployment rate increases the likelihood that the respective District president will dissent in favor of looser policy [that is, a lower federal funds rate target than the majority of the committee preferred] at the FOMC by around 9 percentage points.” The authors note that: “The influence of local economic conditions on dissents by District presidents reflects the regional structure of the Federal Reserve System, which was designed to accommodate diverse views across the nation.” (The full text of the paper can be found here. A summary of the paper’s findings by Ulate and Caroline Paulson and Aditi Poduri of the San Francisco Fed can be found here.)