Chair Jerome Powell at a meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (photo from federalreserve.gov)

At the beginning of the year, there was an expectation among some economists and policymakers that the Fed’s policy-making Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) would begin cutting its target range for the federal funds rate at the meeting that ended today (May 1). The Fed appeared to be bringing the U.S. economy in for a soft landing—inflation returning to the Fed’s 2 percent target without a recession occurring.

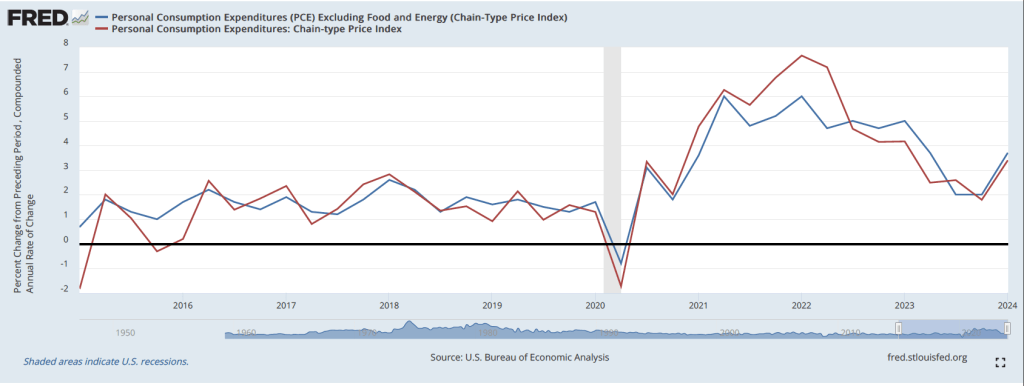

During the first quarter of 2024, production and employment have been expanding more rapidly than had been expected and inflation has been higher than expected. As a result, the nearly universal expectation prior to this meeting was that the FOMC would leave its target for the federal funds rate unchanged. Some economists and investment analysts have begun discussing the possiblity that the committee might not cut its target at all during 2024. The view that interest rates will be higher for longer than had been expected at the beginning of the year has contributed to increases in long-term interest rates, including the interest rates on the 10-year Treasury Note and on residential mortgage loans.

The statement that the FOMC issued after the meeting confirmed the consensus view:

“Recent indicators suggest that economic activity has continued to expand at a solid pace. Job gains have remained strong, and the unemployment rate has remained low. Inflation has eased over the past year but remains elevated. In recent months, there has been a lack of further progress toward the Committee’s 2 percent inflation objective.”

In his press conference after the meeting, Fed Chair Jerome Powell emphasized that the FOMC was unlikely to cut its target for the federal funds rate until data indicated that the inflation rate had resumed falling towards the Fed’s 2 percent target. At one point in the press conference Powell noted that although it was taking longer than expected for the inflation rate to decline he still expected that the pace of economic actitivity was likely to slow sufficiently to allow the decline to take place. He indicated that—contrary to what some economists and investment analysts had suggested—it was unlikely that the FOMC would raise its target for the federal funds rate at a future meeting. He noted that the possibility of raising the target was not discussed at this meeting.

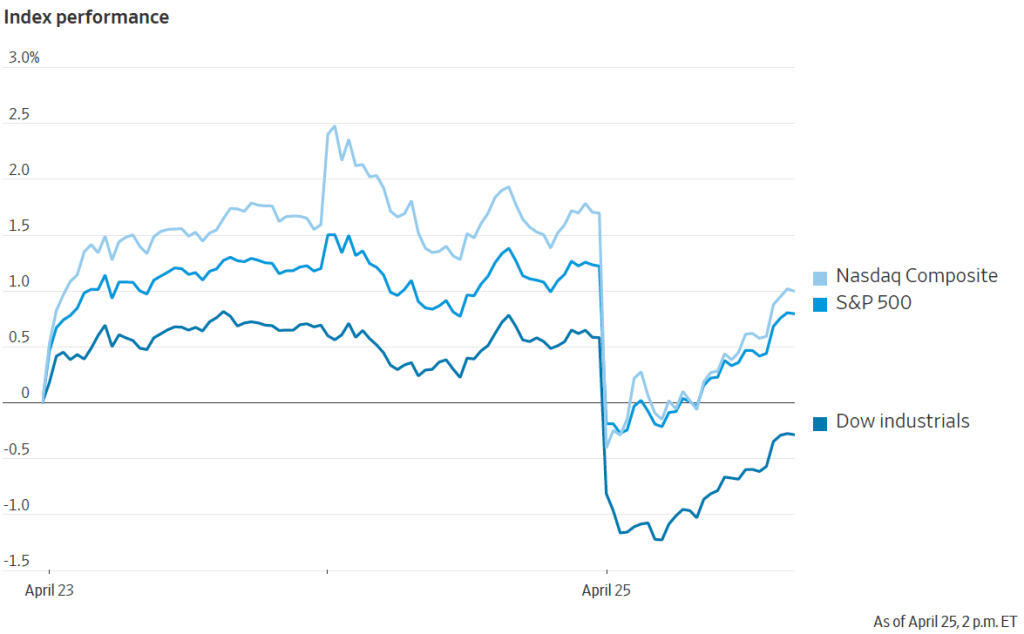

Was there any news in the FOMC statement or in Powell’s remarks at the press conference? One way to judge whether the outcome of an FOMC meeting is consistent with the expectations of investors in financial markets prior to the meeting is to look at movements in stock prices during the time between the release of the FOMC statement at 2 pm and the conclusion of Powell’s press conference at about 3:15 pm. The following figure from the Wall Street Journal, shows movements in the three most widely followed stock indexes—the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the S&P 500, and the Nasdaq composite. (We discuss movements in stock market indexes in Macroeconomics and Essentials of Economics, Chapter 6, Section 6.2 and in Economics, Chapter 8, Section 8.2.)

If either the FOMC statement or the Powell’s remarks during his press conference had raised the possibility that the committee was considering raising its target for the federal funds rate, stock prices would likely have declined. The decline would reflect investors’ concern that higher interest rates would slow the economy, reducing future corporate profits. If, on the other hand, the statement and Powell’s remarks indicated that the committee would likely cut its target for the federal funds rate relatively soon, stock prices would likely have risen. The figure shows that stock prices began to rise after the 2 pm release of the FOMC statement. Prices rose further as Powell seemed to rule out an increase in the target at a future meeting and expressed confidence that inflation would resume declining toward the 2 percent target. But, as often happens in the market, this sentiment reversed towards the end of Powell’s press conference and two of the three stock indexes ended up lower at the close of trading at 4 pm. Presumably, investors decided that on reflection there was no news in the statement or press conference that would change the consensus on when the FOMC might begin lowering its target for the federal funds rate.

The next signficant release of macroeconomic data will come on Friday when the Bureau of Labor Statistics issues its employment report for April.