Image generated by ChatGPT

Beginning in 1933, under the Federal Reserve’s Regulation Q, commercial banks were prohibited from paying interest on checking account deposits. As we discuss in Money, Banking, and the Financial System, Chapter 12, Section 12.4, in 1980 Congress allowed banks to pay interest on Negotiable Order of Withdrawal (NOW) accounts. Because NOW accounts effectively functioned as checking accounts, many people moved funds out of checking accounts and into NOW accounts.

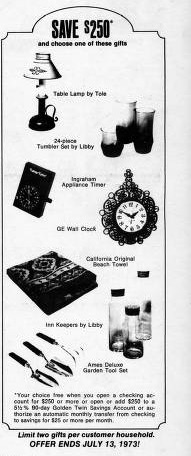

Once NOW accounts were available, a bank could try to attract deposits by offering higher interest rates. But what did a bank do to attract deposits prior to 1980 when it couldn’t legally pay interest? Many banks offered rewards, such as toasters, clock radios, or other small appliances, to people who opened a new checking account or made a large deposit. Banks heavily advertised these rewards on television and radio and in newspapers. The 1960s and 1970s are sometimes called “the free-toaster era” in banking. For example, in 1973, the Marquette National Bank placed this advertisement in a local Minneapolis newspaper offering a variety of gifts to anyone depositing $250 or more in a checking account.

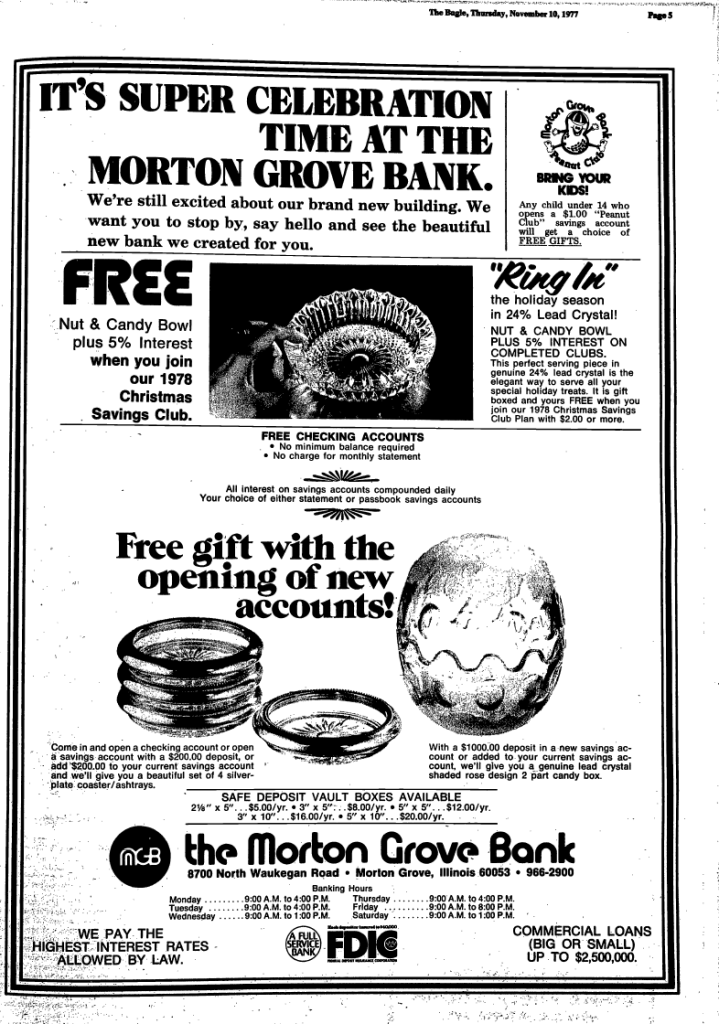

In 1977, a bank in Morton Grove, Illinois offered candy bowls and ashtrays to people opening new accounts.

Congress authorized NOW accounts because as interest rates rose during the 1970s—despite the offers of free gifts—banks were losing deposits to money market mutual funds and other short-term financial assets such as Treasury bills. Today, banks are afraid that they will lose deposits to cryptocurrencies, particularly stablecoins. As we discuss in this blog post, stablecoins are a type of cryptocurrency—bitcoin is the best-known cryptocurrency—that can be bought and sold for a constant number of units of a currency, usually U.S. dollars. Typically, one stablecoin can be exchanged for one dollar.

In July 2025, Congress passed and President Trump signed the Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for U.S. Stablecoins Act (Genius Act) to provide a regulatory framework for stablecoins. Firms issuing stablecoins earn income on the assets, such as Treasury bills and money market funds that invest in Treasury bills, that they are required to hold to back the stablecoins they issue. But a provision of the Act bars issues of stablecoins from paying interest to holders of stablecoins. So, stablecoin issuers can’t copy the strategy of banks by paying interest to attract deposits and funding the interest on deposits with the interest earnings on their assets.

To this point, few people are buying stablecoins unless they intend to use them in buying and selling bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies or unless they need a convenient way to transfer funds across national borders. Some of these international transfers are related to drug dealing and other illegal activities. Because few retail firms—either brick-and-mortar or online—are equipped to accept stablecoins in payment for goods and services, and because stablecoins pay no interest, most households and firms don’t see stablecoins as good substitutes for checking accounts in banks.

As we discuss in Chapter 12 of Money, Banking, and the Financial System, when the federal government adopts new financial regulations, like the Genius Act, financial firms often respond by attempting to evade the regulations. People buy and sell cryptocurrencies on exchanges, such as Coinbase. Circle issues the stablecoin USDC and has agreed to pay Coinbase some of the interest it earns on Circle’s assets. As the following screenshot from the Coinbase site shows, Coinbase offers to pay interest to anyone who holds USDC on the Coinbase site.

An article in the Wall Street Journal notes that: “The result is something that critics say looks a lot like a yield-bearing stablecoin. Coinbase says the reward program is separate from its revenue-sharing deal with Circle.” If other stablecoins attract funds by offering interest payments in this indirect way and if more retailers begin to accept stablecoins as payment for goods and services—which they have an incentive to do to avoid the 1 percent to 3 percent fee that credit card issuers charge retailers on purchases—banks stand to lose trillions in deposits.

Smaller banks, often called community banks, might be most at risk from deposit outflows because they are more reliant on deposits to fund their investments than are larger banks. As we discuss in Money, Banking, and the Financial System, Chapter 9, community banks practice relationship banking by using private information to assess the credit risk involved in lending to local borrowers, such as car dealers and restaurants. Many large banks believe that the transaction costs involved in evaluating risk on small business loans make such loans unprofitable. So the disappearance of many community banks may make it more difficult for small businesses to access the credit they need to operate.

The Bank Policy Institute (BPI), which lobbies on behalf of the banking industry, argues that:

“Stablecoin issuers want to engage in banking activities, like paying interest. Being a bank requires the full suite of regulatory requirements, deposit insurance and discount window access that keep banks safe. Stablecoins seeking to offer banking services must be subject to those requirements and protections, rather than using workarounds and backdoors to pay interest, take deposits and access the federal payment rails.”

BPI urges Congress to eliminate the ability of Coinbase and other crypto exhanges to help stablecoin issuers evade the prohibition on paying interest.

If the prohibition on stablecoin issuers paying interest is tightened, how else might issuers attract people to invest in stablecoins? Well, there’s always free toasters!